Ms Y Omar V Brampton Manor Trust: 3201876/2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

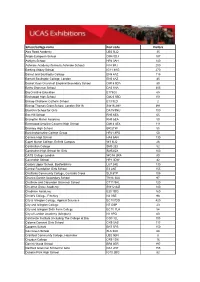

College Open Day List

Open Events 2019-2020 Please check the sixth form/college website to confirm dates and times of open events, as they may be subject to change, and new dates may be added You will also need to check if you need to register in advance or attend with a parent/carer Places to study in Newham Brampton Manor Academy November 2019 (Date to be confirmed in September – Roman Road E6 3SQ check website regularly) 020 7540 0500 / bramptonmanor.org [email protected] Booking required via website The Building Crafts College Open every Thursday 1pm-4pm Kennard Road, London E15 1HA Online application form 020 8552 1705 / thebcc.ac.uk / [email protected] Chobham Academy No dates released yet, check the website regularly for 40 Cheering Lane, London E20 1BD information 020 3747 6060 / chobhamacademy.org.uk [email protected]. (Open day usually in November, check website regularly) uk ELAM (East London Arts & Music) Thursday 7 November 2019, 5pm-7pm 45a Maltings Close, London E3 3TA Arrive 5pm for 5.30pm talk 020 75152159 / elam.co.uk [email protected] Arrive 6pm for 6.30pm talk No admission after 6.30pm Bookings via website Applications are now open for 2020 London Academy of Excellence Wednesday 30 October 2019, 4pm-8pm Broadway House, 322 High Street, London E15 1JA Wednesday 13 November 2018, 4pm-8pm 020 3301 1480 / excellencelondon.ac.uk / Sat 23 November 2019, 10am-4pm [email protected] Booking required via website which will open at the beginning of October Applications open Monday 28th October 2019 London Design -

17 July 2015 Name & Tutor Group

Issue 41 Working together to promote & celebrate achievement 17 July 2015 Name & Tutor Group: Headlines by Rachel McGowan Staff News During this half-term, Mrs Mary Ward, a member of our reception team, retired from the school having served our school community for 21 years. Whilst not everyone in our community will have met Mrs Ward face-to-face, by the nature of her job many of you will have spoken to her over the phone. Throughout her service to the school, Mrs Ward has been a consummate professional in all her dealings with youngsters, families, visitors and staff and is much missed as she commences a very well earned retirement. On behalf of our whole school community can I thank her for her outstanding contribution to the school and wish her a long and happy retirement. A number of staff will be leaving us at the end of this academic year, most notably Mrs Sue Rosner, who has been a teacher here at Plashet since 1980 and Assistant Headteacher since 1997. Mrs Rosner has served the school with great distinction throughout this period holding a wide range of different responsibilities. As well as being a fantastic contributor to the leadership of our whole school she has worked closely with a number of different Cohorts as their senior line manager. As a teacher of Drama she has consistently demanded the highest possible standards from students in her own classes, and the quality of teaching she has demonstrated has been an inspiration to less experienced members of staff who will miss her wise counsel. -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors Alec Reed Academy UB5 5LQ 35 Anglo-European School CM4 0DJ 187 Ashlyns School HP4 3AH 140 Ashmole Academy (formerly Ashmole School) N14 5RJ 200 Barking Abbey School IG11 9AG 270 Barnet and Southgate College EN5 4AZ 115 Barnett Southgate College, London EN5 4AZ 45 Becket Keys Church of England Secondary School CM15 9DA 80 Beths Grammar School DA5 1NA 305 Big Creative Education E175QJ 65 Birchwood High School CM23 5BD 151 Bishop Challoner Catholic School E13 9LD 2 Bishop Thomas Grant School, London SW16 SW16 2HY 391 Blackfen School for Girls DA15 9NU 100 Box Hill School RH5 6EA 65 Brampton Manor Academy RH5 6EA 50 Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School CM14 4EX 111 Bromley High School BR!2TW 55 Buckinghamshire College Group HP21 8PD 50 Canons High School HA8 6AN 130 Capel Manor College, Enfield Campus W3 8LQ 26 Carshalton College SM5 2EJ 52 Carshalton High School for Girls SM52QX 100 CATS College London WC1A 2RA 80 Cavendish School HP1 3DW 42 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE 130 Central Foundation Girls School E3 2AE 155 Chalfonts Community College, Gerrards Cross SL9 8TP 105 Charles Darwin Secondary School TN16 3AU 97 Chatham and Clarendon Grammar School CT11 9AL 120 Chestnut Grove Academy SW12 8JZ 140 Chobham Academy E20 1DQ 160 Christ's College, Finchley N2 0SE 98 City & Islington College, Applied Sciences EC1V7DD 420 City and Islington College N7 OSP 23 City and Islington Sixth Form College EC1V 7LA 54 City of London Academy (Islington) N1 8PQ 60 Colchester Institute (including The College -

Sixth Form Newsletter 29Th January 2018

Sixth Form Newsletter 29th January 2018 Head of Sixth Form’s Welcome It has been a busy week! Our Year 12 students received their reports on Tuesday and we will be hosting Progress Meetings for parents and carers on Wednesday 31st January from 4pm-7pm. Our applications for September 2018 closed on Friday and we are delighted to have received 350 applications from students from INA and local schools such as Beal High School, Seven Kings High School and Brampton Manor Academy. Interviews will take place on Monday 19th February which will be an Independent Learning day for Sixth Form students. Our Psychology students attended a talk on Wednesday entitled ‘The Real Causes Key Dates of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions’ with Johann Hari. The talk was thought-provoking and probing. The causes of depression were scrutinised; Hari 30th Jan - Head Student Voting Closes criticised the shift in our culture towards ‘junk values’ which he felt was contributing (Staff and Year 12 students can vote via Fronter) to a lack of fulfilment around our basic human needs. Hari urged the audience st to consider broadening the vision of what could be termed as an anti-depressant 31 Jan - Year 12 Progress Meetings (4pm-7pm) and offering a more holistic approach to managing the causes of depression. The lecture was hosted by 6th Feb - Year 12 Berlin Trip Meeting the How To: Academy and we are grateful for their (6pm-7pm. For Parents of students attending generous support with tickets to this event. the History Trip to Berlin. ) We look forward to seeing parents and carers at the 7th Feb - Year 8 Progress Meetings Sixth Form Progress meeting this week. -

Celebrating Women in Aviation

A2_poster_portrait.pdf 1 19/02/2019 16:32 Spring edition 2019 Stay well away from aircraft, airports and airfields Celebrating when flying any drone. 1 Km women in aviation 5 Km 1 Km 5 Km 5 Km 1 Km C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 5 Km 2 or 2.5nm 1 Km International From 13th March it is illegal to fly them inside the Women’s Day London City working to achieve a airport’s flight restriction zone without permission. better gender balance City Airport Police Project Servator, new tactics of See dronesafe.uk for info policing, and drone deterrence What’s on locally Find out what’s on in your local area If your drone endangers the safety Empowering women in North Woolwich of an aircraft it is a criminal offence Fight for peace uses combat sport training and you could go to prison for five years £500M transformation See concept images of our future airport A new brand identity The London City Airport Brand gets dronesafe.uk a makeover Contents Hello and welcome to your latest edition of Inside E16 community magazine. 1 – 2 Welcome from Read on to find out more about what’s happening in and around London Alexandra Varlyakova City Airport - including a recap of 2018 volunteering highlights; the latest Meet London City from our £500 million airport transformation, record passenger figures, Airport’s Public Affairs and a new brand identity for the airport. and Policy Manager We want this magazine to serve a broader purpose than to just update you on airport news. -

Download the Ofsted Report As A

King’s College London Initial Teacher Education inspection report Inspection Dates Stage 1: 18/05/2015 Stage 2: 28/09/2015 This inspection was carried out by Her Majesty’s Inspectors, in accordance with the Initial teacher education inspection handbook. This handbook sets out the statutory basis and framework for initial teacher education (ITE) inspections in England from April 2015. The inspection draws upon evidence from within the ITE partnership to make judgements against all parts of the evaluation schedule. Inspectors focused on the overall effectiveness of the ITE partnership in securing high-quality outcomes for trainees. Inspection judgements Key to judgements: Grade 1 is outstanding; grade 2 is good; grade 3 is requires improvement; grade 4 is inadequate Secondary QTS Overall Effectiveness 1 How well does the partnership secure consistently high quality outcomes for trainees? The outcomes for trainees 1 The quality of training across 1 the partnership The quality of leadership and 1 management across the partnership ITE inspection report September 2015 1 The secondary phase Information about the secondary partnership King’s College London provides initial teacher training to 223 trainees in the secondary phase, which is slightly more than at the time of the last inspection. The partnership offers three routes to qualified teacher status (QTS) for graduate trainees who wish to teach students in the 11–18 age range. Most trainees follow a provider-led core programme aimed at achieving QTS alongside masters-level assignments leading to a post- graduate certificate of education (PGCE). A small number, 17 trainees in 2014/15, follow a school direct non- salaried route, which has the same programme content as the core PGCE route but where a partner school has responsibility for the trainee’s recruitment and teaching placements. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

Brampton Manor Academy, Roman Road in the London Borough of Newham Planning Application No.18/02203/LA3

planning report GLA/4825/01 25 September 2018 Brampton Manor Academy, Roman Road in the London Borough of Newham planning application no.18/02203/LA3 Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008. The proposal Full planning application for construction of a new three-storey teaching facility with sports and community facilities; a two-storey extension to the existing sixth-form, extension to the existing staffroom and library facilities, and landscaping works. The proposal also includes relocation of the seasonal athletics and track provision, MUGA and artificial pitch with flood lights. The applicant The applicant is Brampton Manor Academy, and the architect is Rivington Street Studio. Strategic issues summary Principle of development: The proposal results in the loss of open space; however, this is justified on balance given that the educational need, community benefits, as well as the quantitative and qualitative improvements in sports provision, clearly outweigh the loss. The proposal accords with London Plan and draft London Plan policies related to education, sports provision and open space. (paragraphs 14 to 29). Urban and inclusive design: The Council must secure details of the landscaping and key materials, and approach to inclusive design by condition (paragraphs 30 to 34). Sustainable development: A revised energy statement that demonstrates carbon savings meet the target set out within Policy 5.2 of the London Plan and Policy SI2 of the draft London Plan must be submitted. A drainage strategy that accords with policies of the London Plan and draft London Plan must be secured by condition (paragraphs 35 to 39). -

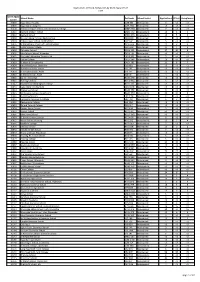

2017 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2017 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 7 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 13 6 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 5 5 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 5 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 11 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 17 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 10 8 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 21 8 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 4 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU -

Oasis Academy Silvertown

Annex B: Impact Assessment – Section 9 Academies Act Duty: Oasis Academy Silvertown Distance from free school School Attainment in School name (miles) type Capacity 2012/13 Ofsted grade Impact rating Overall 11-16 age High range 1200 school places The Royal Docks Community School This school will potentially feel a high Overall surplus of 230 impact from Oasis Silvertown Foundation school places (19.2% of opening. The school has a surplus School total school capacity) Well below Requires of place, especially at entry point, average Improvement below average attainment in KS4 results and received a requires 0.7 improvement in the latest Ofsted inspection. Opening Oasis At entry point Not a faith Silvertown could mean Royal Docks school has fewer pupils and becomes financially unviable. 240 places 50% of pupils Date of most 89 entry level places achieved 5A*-C recent Ofsted Mixed unfilled in 12/13 inc English and inspection: maths. 15/03/2013 Overall 11-16 age Moderate range 900 school places Well below Rokeby School 1.1 Good average The school has performed well in Overall surplus of 72 Community their most recent Ofsted inspection school places (8.0% of School and attainment is improving. The total school capacity) school is an all-boys school and has 1 a different educational offer to Oasis Silvertown. The free school is At entry point Not a faith unlikely to affect the long term school financial viability of the school 180 places 38% of pupils Date of most 19 entry level places achieved 5A*-C recent Ofsted Boys unfilled in 12/13 inc English and inspection: maths. -

College Open Day List

Open Events 2019 Please check the Sixth Form/College website to confirm dates/ times as they may be subject to change. You will also need to check if you need to register in advance or attend with a parent/career. I Places to study in Newham Brampton Manor Academy Will take place in November. Check website for further Roman Road E6 3SQ info. 020 7540 0500 / bramptonmanor.org Booking required via website [email protected] The Building Crafts College Open every Thursday , 1pm - 4 pm Kennard Road, London E15 1HA Online application form 020 8552 1705 / thebcc.ac.uk / [email protected] Chobham Academy Thursday 15th November 2018,4.30pm – 7:30pm 40 Cheering Lane, London. E20 1BD Check website for further information 020 3747 6060 / chobhamacademy.org.uk Online application form [email protected] ELAM (East London Arts & Music) Thursday 15th November 2018, 5pm -7pm 45 Maltise, London. E3 3TA 020 75152159 / elam.co.uk [email protected] London Academy of Excellence Wednesday 31st October 2018, 4pm – 8pm Broadway House, 322 High Street, London E15 1JA Wednesday 14th November 2018, 4pm – 8pm 020 3301 1480 / excellencelondon.ac.uk / Sat 24th November 2018, 10am – 4pm [email protected] Booking required via website which will open end of September beginning of October London Design & Engineering UTC Tuesday 16 th October 2018, 6pm - 7pm Docklands Campus, University Way, London E16 2RD Wednesday 14th November2018, 6pm – 7pm 020 3019 7333 / ldeutc.ac.uk /[email protected] Tuesday 4th December 2018, 6pm – 8pm Tuesday 29th January 2019, 6pm – 8pm Booking required via website Apply by 18th January 2019 Newham College of FE No dates released yet East Ham Campus (EH): High Street South, London. -

Determined School Admission Arrangements for Secondary Schools for Entry from September 2018

Determined School Admission Arrangements for Secondary Schools For entry from September 2018 The Governing Body of each Own Admission Authority School located in Newham, has the option to adopt part or all of these arrangements. See Appendix 3 for full details Intellectual property of LB Newham Author Tracy Jones Pupil Services Page 1 Introduction and overview For the purpose of this document, the universal term ‘school’, will be used when referring to all state funded academies, community schools, free schools, studio schools, university technical colleges, voluntary aided faith schools and voluntary controlled faith schools. All admissions authorities for state funded schools in England must comply with the current Schools Admissions Code which is produced by Department for Education and sets out the law and guidance relating to school admissions. Local authorities have an important role in monitoring compliance with the Admissions Code and are required to report annually to the Schools Adjudicator on the fairness and legality of the admissions arrangements for all schools in their area, including those for whom they are the admissions authority. As the Admissions Authority for the community and voluntary controlled infant, junior and primary schools located in Newham, the local authority is required to draft, consult on and determine their admission arrangements including the oversubscription criteria for each new academic year. Admission arrangements for state funded non fee paying independent academies, free schools university technical colleges (UTC) and voluntary aided faith schools located in Newham are set by their own Academy Trust/Governing Body, who are the Admission Authority. They are responsible for drafting, consulting and determining their own admission arrangements.