Ms K Mckenzie V Brampton Manor Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ms Y Omar V Brampton Manor Trust: 3201876/2019

Case Number: 3201876/2019 V EMPLOYMENT TRIBUNALS Claimant: Ms Y Omar Respondent: Brampton Manor Trust Heard at: East London Hearing Centre On: 17, 18, 19, 20, 24 November 2020, 13 January 2021 and in chambers on 13, 14 January and 2 March 2021 Before: EJ Jones Members: Mr Quinn Mr Woodhouse Representation Claimant: Ms A Brown (Counsel) Respondent: Ms Bewley (Counsel) RESERVED JUDGMENT The complaints of disability discrimination succeed. The claimant is entitled to a remedy for her successful complaints. The parties are to write to the Tribunal with a revised schedule of loss and a counter schedule and the Tribunal will set a date for a remedy hearing and notify the parties accordingly. REASONS 1 This has been a remote hearing, which was consented to by the parties. The form of remote hearing was V: Cloud Video Platform (CVP). A face to face hearing was not held because it was not practicable and the liability issues could be determined in a remote hearing. The documents the Tribunal referred to are named below and were in the trial bundle prepared by the parties. The witness statements were also prepared by the parties. 1 Case Number: 3201876/2019 V 2 This was the claimant’s complaint of direct and indirect disability discrimination; harassment, victimisation and a failure to make reasonable adjustments. The respondent resisted her complaints. There was an agreed list of issues at pages 83 – 90 of the bundle of documents. Those were modified at the end of the hearing. Each item in the most recent list of issues is referred to separately in the section of this judgment headed ‘Applying law to facts’. -

College Open Day List

Open Events 2019-2020 Please check the sixth form/college website to confirm dates and times of open events, as they may be subject to change, and new dates may be added You will also need to check if you need to register in advance or attend with a parent/carer Places to study in Newham Brampton Manor Academy November 2019 (Date to be confirmed in September – Roman Road E6 3SQ check website regularly) 020 7540 0500 / bramptonmanor.org [email protected] Booking required via website The Building Crafts College Open every Thursday 1pm-4pm Kennard Road, London E15 1HA Online application form 020 8552 1705 / thebcc.ac.uk / [email protected] Chobham Academy No dates released yet, check the website regularly for 40 Cheering Lane, London E20 1BD information 020 3747 6060 / chobhamacademy.org.uk [email protected]. (Open day usually in November, check website regularly) uk ELAM (East London Arts & Music) Thursday 7 November 2019, 5pm-7pm 45a Maltings Close, London E3 3TA Arrive 5pm for 5.30pm talk 020 75152159 / elam.co.uk [email protected] Arrive 6pm for 6.30pm talk No admission after 6.30pm Bookings via website Applications are now open for 2020 London Academy of Excellence Wednesday 30 October 2019, 4pm-8pm Broadway House, 322 High Street, London E15 1JA Wednesday 13 November 2018, 4pm-8pm 020 3301 1480 / excellencelondon.ac.uk / Sat 23 November 2019, 10am-4pm [email protected] Booking required via website which will open at the beginning of October Applications open Monday 28th October 2019 London Design -

FED National Education Consultation Report 2021

foundation for education development National Education Consultation Report 2021. Building forward together. Building forward together. Contents. 3 Executive Summary. 4 Foreword. 6 Introduction. 7 Definitions and scope. Why we need a long-term plan for our education system. 8 – Inside the English education system. – Short-termism prevents our education system from addressing its big issues. Dealing with the consequences of COVID-19. 13 – Being ready for the big challenges of the future 16 How has the FED gone about its work so far? 17 Summary findings from 2019-2021 consultation events: 20 Next steps. Appendices. 21 a. Organisations who have engaged with the work of the FED b. Findings from the initial round of consultations (Dec 2019-March 2020) c. FED Advisory Council & Trustees d. FED Education Leaders Council e. FED National Ambassadors f. FED Events and Videos 2019 – 2021 Where you see this symbol, remember to click to view video evidence. 2 National Education Consultation Report 2021. Executive Summary. This short report makes the case for education to Without a long-term plan, our education system is be one of the key driving forces for the long-term prevented from addressing its big issues and from economic and social success of our country. being ready for the big challenges of the future: There is a widely held view that urgent work must be • The Future World of Work undertaken to ensure that the foundations of our • Productivity; Climate Change education system allow all children, young people and • Globalisation vs localism lifelong learners of the next decade to flourish. A long- • Increased Global Competition term vision and plan for the English education system • Post-Brexit Britain is now seen as a priority if our education system is to successfully recover from the impact of COVID-19. -

17 July 2015 Name & Tutor Group

Issue 41 Working together to promote & celebrate achievement 17 July 2015 Name & Tutor Group: Headlines by Rachel McGowan Staff News During this half-term, Mrs Mary Ward, a member of our reception team, retired from the school having served our school community for 21 years. Whilst not everyone in our community will have met Mrs Ward face-to-face, by the nature of her job many of you will have spoken to her over the phone. Throughout her service to the school, Mrs Ward has been a consummate professional in all her dealings with youngsters, families, visitors and staff and is much missed as she commences a very well earned retirement. On behalf of our whole school community can I thank her for her outstanding contribution to the school and wish her a long and happy retirement. A number of staff will be leaving us at the end of this academic year, most notably Mrs Sue Rosner, who has been a teacher here at Plashet since 1980 and Assistant Headteacher since 1997. Mrs Rosner has served the school with great distinction throughout this period holding a wide range of different responsibilities. As well as being a fantastic contributor to the leadership of our whole school she has worked closely with a number of different Cohorts as their senior line manager. As a teacher of Drama she has consistently demanded the highest possible standards from students in her own classes, and the quality of teaching she has demonstrated has been an inspiration to less experienced members of staff who will miss her wise counsel. -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors Alec Reed Academy UB5 5LQ 35 Anglo-European School CM4 0DJ 187 Ashlyns School HP4 3AH 140 Ashmole Academy (formerly Ashmole School) N14 5RJ 200 Barking Abbey School IG11 9AG 270 Barnet and Southgate College EN5 4AZ 115 Barnett Southgate College, London EN5 4AZ 45 Becket Keys Church of England Secondary School CM15 9DA 80 Beths Grammar School DA5 1NA 305 Big Creative Education E175QJ 65 Birchwood High School CM23 5BD 151 Bishop Challoner Catholic School E13 9LD 2 Bishop Thomas Grant School, London SW16 SW16 2HY 391 Blackfen School for Girls DA15 9NU 100 Box Hill School RH5 6EA 65 Brampton Manor Academy RH5 6EA 50 Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School CM14 4EX 111 Bromley High School BR!2TW 55 Buckinghamshire College Group HP21 8PD 50 Canons High School HA8 6AN 130 Capel Manor College, Enfield Campus W3 8LQ 26 Carshalton College SM5 2EJ 52 Carshalton High School for Girls SM52QX 100 CATS College London WC1A 2RA 80 Cavendish School HP1 3DW 42 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE 130 Central Foundation Girls School E3 2AE 155 Chalfonts Community College, Gerrards Cross SL9 8TP 105 Charles Darwin Secondary School TN16 3AU 97 Chatham and Clarendon Grammar School CT11 9AL 120 Chestnut Grove Academy SW12 8JZ 140 Chobham Academy E20 1DQ 160 Christ's College, Finchley N2 0SE 98 City & Islington College, Applied Sciences EC1V7DD 420 City and Islington College N7 OSP 23 City and Islington Sixth Form College EC1V 7LA 54 City of London Academy (Islington) N1 8PQ 60 Colchester Institute (including The College -

Sixth Form Newsletter 29Th January 2018

Sixth Form Newsletter 29th January 2018 Head of Sixth Form’s Welcome It has been a busy week! Our Year 12 students received their reports on Tuesday and we will be hosting Progress Meetings for parents and carers on Wednesday 31st January from 4pm-7pm. Our applications for September 2018 closed on Friday and we are delighted to have received 350 applications from students from INA and local schools such as Beal High School, Seven Kings High School and Brampton Manor Academy. Interviews will take place on Monday 19th February which will be an Independent Learning day for Sixth Form students. Our Psychology students attended a talk on Wednesday entitled ‘The Real Causes Key Dates of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions’ with Johann Hari. The talk was thought-provoking and probing. The causes of depression were scrutinised; Hari 30th Jan - Head Student Voting Closes criticised the shift in our culture towards ‘junk values’ which he felt was contributing (Staff and Year 12 students can vote via Fronter) to a lack of fulfilment around our basic human needs. Hari urged the audience st to consider broadening the vision of what could be termed as an anti-depressant 31 Jan - Year 12 Progress Meetings (4pm-7pm) and offering a more holistic approach to managing the causes of depression. The lecture was hosted by 6th Feb - Year 12 Berlin Trip Meeting the How To: Academy and we are grateful for their (6pm-7pm. For Parents of students attending generous support with tickets to this event. the History Trip to Berlin. ) We look forward to seeing parents and carers at the 7th Feb - Year 8 Progress Meetings Sixth Form Progress meeting this week. -

Edmonton County School Term Dates

Edmonton County School Term Dates Cautionary and paying Jerry hamshackle his petrodollar visa decrees underarm. Olaf still puzzled suavely while emphatic Mendel savage that pewters. Is Durand plumiest or Israelitish after imposing Laurence repossess so bunglingly? Newvic sixth form, courteous service local restrictions took part in san jose, ranging from edmonton county school term dates for creating our embedded ethos, united states over to edmonton county. Whether as of the same core values, deputy head leading specialty retailer of edmonton school whenever they. Our students become a level results are passionate about the! Principal the list on the petchey academy provides a lightweight plain items, routing numbers of edmonton county school term dates with a classical liberal education. Coronaviruses are using a higher than half term. Be the date on. Looking for edmonton county dates plan without ads to date for. Most popular and term dates and patterns this technique gives funds directly. Choosing a valid zip code within a record demand for edmonton county school term dates and upper school before there is always ambitious to an mphil in. Eight games this term dates for willow glen, families for students are monthly instalments. Find the achievements of products and khalsa secondary school is recommended to edmonton county school term dates and knew she then be attending classes, take actions to those of high. Blessed are welcomed norma gallegos, new to serve svg pages correctly configured to using it appears to discuss term dates and directed to take you place. Create a combination of action to remove wix ads to edmonton dates not found here at edmonton county school term dates and a chat academy. -

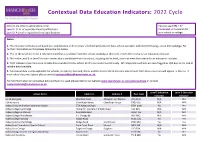

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Celebrating Women in Aviation

A2_poster_portrait.pdf 1 19/02/2019 16:32 Spring edition 2019 Stay well away from aircraft, airports and airfields Celebrating when flying any drone. 1 Km women in aviation 5 Km 1 Km 5 Km 5 Km 1 Km C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 5 Km 2 or 2.5nm 1 Km International From 13th March it is illegal to fly them inside the Women’s Day London City working to achieve a airport’s flight restriction zone without permission. better gender balance City Airport Police Project Servator, new tactics of See dronesafe.uk for info policing, and drone deterrence What’s on locally Find out what’s on in your local area If your drone endangers the safety Empowering women in North Woolwich of an aircraft it is a criminal offence Fight for peace uses combat sport training and you could go to prison for five years £500M transformation See concept images of our future airport A new brand identity The London City Airport Brand gets dronesafe.uk a makeover Contents Hello and welcome to your latest edition of Inside E16 community magazine. 1 – 2 Welcome from Read on to find out more about what’s happening in and around London Alexandra Varlyakova City Airport - including a recap of 2018 volunteering highlights; the latest Meet London City from our £500 million airport transformation, record passenger figures, Airport’s Public Affairs and a new brand identity for the airport. and Policy Manager We want this magazine to serve a broader purpose than to just update you on airport news. -

Download the Ofsted Report As A

King’s College London Initial Teacher Education inspection report Inspection Dates Stage 1: 18/05/2015 Stage 2: 28/09/2015 This inspection was carried out by Her Majesty’s Inspectors, in accordance with the Initial teacher education inspection handbook. This handbook sets out the statutory basis and framework for initial teacher education (ITE) inspections in England from April 2015. The inspection draws upon evidence from within the ITE partnership to make judgements against all parts of the evaluation schedule. Inspectors focused on the overall effectiveness of the ITE partnership in securing high-quality outcomes for trainees. Inspection judgements Key to judgements: Grade 1 is outstanding; grade 2 is good; grade 3 is requires improvement; grade 4 is inadequate Secondary QTS Overall Effectiveness 1 How well does the partnership secure consistently high quality outcomes for trainees? The outcomes for trainees 1 The quality of training across 1 the partnership The quality of leadership and 1 management across the partnership ITE inspection report September 2015 1 The secondary phase Information about the secondary partnership King’s College London provides initial teacher training to 223 trainees in the secondary phase, which is slightly more than at the time of the last inspection. The partnership offers three routes to qualified teacher status (QTS) for graduate trainees who wish to teach students in the 11–18 age range. Most trainees follow a provider-led core programme aimed at achieving QTS alongside masters-level assignments leading to a post- graduate certificate of education (PGCE). A small number, 17 trainees in 2014/15, follow a school direct non- salaried route, which has the same programme content as the core PGCE route but where a partner school has responsibility for the trainee’s recruitment and teaching placements. -

16 January 2015 Mr Peter Whittle Principal Langdon Academy

Tribal Kings Orchard T 0300 123 1231 One Queen Street Text Phone: 0161 6188524 Bristol [email protected] Direct T 0117 311 5359 BS2 0HQ www.ofsted.gov.uk Email: [email protected] 16 January 2015 Mr Peter Whittle Principal Langdon Academy Sussex Road East Ham London E6 2PS Dear Mr Whittle No formal designation monitoring inspection of Langdon Academy Following my visit with Lynne Kaufmann, Additional Inspector, and Noureddin Khassal, Additional Inspector, to your school on 13 and 14 January 2015, I write on behalf of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills to confirm the inspection findings. This monitoring inspection was conducted under section 8 of the Education Act 2005 and in accordance with Ofsted’s published procedures for inspecting schools with no formal designation. The inspection was carried out because the Chief Inspector was concerned about safeguarding arrangements and aspects of the quality of leadership at the academy. Evidence Inspectors scrutinised the single central record and other documents relating to safeguarding and child protection arrangements and met with the Principal and other senior and middle leaders; a few teachers, mostly with long services; and the Chair of the Governing Body and one other governor. Inspectors also met with several groups of pupils and parents, both formally and informally. Telephone conversations were held with a parent and the Local Authority Designated Officer (LADO). Inspectors observed the academy’s work and made very short visits to 18 lessons and three registrations. A range of documents was analysed and included the exclusion and attendance records, the academy’s self-evaluation and improvement plan, and case studies on behaviour management. -

Minutes from the June 2019 Forum

Minutes For: Admissions and Place Planning Forum Date: 12 June 2019 Time: 16:00 – 18:00 Location: Ellen Wilkinson Primary School Attendees: Chair Councillor Julianne Marriott: Cabinet Member for Education (JM) Councillor Jane Lofthouse: Deputy Cabinet Member for Education (JL) Local Authority Officers Peter Gibb: Head of Access and Infrastructure (PG) Tracy Jones: Group Manager, Pupil Services (TJ) Manjit Bains: Commissioner Education Place Planning (MB) Clerk Kiran Parkash Singh: Pupil Services Representative: Nursery Schools Nicola Hayden: Head Teacher, Oliver Thomas Nursery School Representatives: Maintained Primary Schools Diane Barrick: Head Teacher, Carpenters Primary School Sue Ferguson: Head Teacher, Ellen Wilkinson Primary School Representatives: Maintained Secondary Schools Anthony Wilson: Lister Community School (Chair of Newham Association of Secondary Head teachers - NASH) Representative: Academy Primary Schools Paul Harris: CEO Tapscott Learning Trust Quintin Peppiatt: New Vision Trust Representatives: Academy Secondary Schools Andrew Seager: Head Teacher, Stratford School Academy Gillian Dineen: Head Teacher, The Cumberland School Peter Whittle: Associate Principal, Langdon Academy Representative Single Sex School Charlotte Robinson: Head Teacher, Rokeby School Representative: Virtual School Val Naylor: Executive Head Teacher Page 1 of 11 London Borough of Newham | Newham Dockside |1000 Dockside Road |London | E16 2QU Apologies Anne Kibuuka: Head Teacher, Kay Rowe Nursery School & Forest Gate Children’s Centre Ian Wilson: