Dancecult 11(1) Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 8-8-2020 The Banality of the Social: A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing Kati Sudnick Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Sudnick, K. (2020). The Banality of the Social: A Philosophy of Communication of Social Media Influencer Marketing (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1921 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. THE BANALITY OF THE SOCIAL: A PHILOSOPHY OF COMMUNICATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER MARKETING A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Kati Elizabeth Sudnick August 2020 Copyright by Kati Elizabeth Sudnick 2020 THE BANALITY OF THE SOCIAL: A PHILOSOPHY OF COMMUNICATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER MARKETING By Kati Elizabeth Sudnick Approved May 1st, 2020 ________________________________ ________________________________ Ronald C. Arnett, Ph.D. Erik Garrett, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Communication & Associate Professor, Department of Rhetorical Studies Communication & Rhetorical Studies (Committee Chair) (Committee -

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test Free

FREE THE ELECTRIC KOOL-AID ACID TEST PDF Tom Wolfe | 416 pages | 10 Aug 2009 | St Martin's Press | 9780312427597 | English | New York, United States Merry Pranksters - Wikipedia In the summer and fall ofAmerica became aware of a growing movement of young people, based mainly out of California, called the "psychedelic movement. Kesey is a young, talented novelist who has just seen his first book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nestpublished, and who is consequently on the receiving end of a great deal of fame and fortune. While living in Palo Alto and attending Stanford's creative writing program, Kesey signs up to participate in a drug study sponsored by the CIA. The drug they give him is a new experimental drug called LSD. Under the influence of LSD, Kesey begins to attract a band of followers. They are drawn to the transcendent states they can achieve while on the drug, but they are also drawn to Kesey, who is a charismatic leader. They call themselves the "Merry Pranksters" and begin to participate in wild experiments at Kesey's house in the woods of La Honda, California. These experiments, with lights and noise, are all engineered to create a wild psychedelic experience while on LSD. They paint everything in neon Day-Glo colors, and though the residents and authorities of La Honda are worried, there is little they can do, since LSD is not an illegal substance. The Pranksters first venture into the wider world by taking a trip east, to New York, for the publication of Kesey's newest novel. -

The Last of the Hippies

The Last of the Hippies An Hysterical Romance Penny Rimbaud First published in 1982 as part of the Crass record album Christ: The Album, Penny Rimbaud’s The Last of the Hippies is a fiery anarchist polemic centered on the story of his friend, Phil Russell (aka Wally Hope), who was murdered by the State while incarcerated in a men- tal institution. Wally Hope was a visionary and a freethinker, whose life had a pro- found influence on many in the culture of the UK underground and be- yond. He was an important figure in what may loosely be described as the organization of the Windsor Free Festival from 1972 to 1974, as well providing the impetus for the embryonic Stonehenge Free Festival. Wally was arrested and incarcerated in a mental institution after hav- ing been found in possession of a small amount of LSD. He was later released, and subsequently died. The official verdict was that Russell committed suicide, although Rimbaud uncovered strong evidence that SUBJECT CATEGORY Music-Punk/Subculture-UK he was murdered. Rimbaud’s anger over unanswered questions sur- rounding his friend’s death inspired him in 1977 to form the anarchist PRICE punk band Crass. $12.00 In the space of seven short years, from 1977 to their breakup in 1984, ISBN 978-1-62963-103-5 Crass almost single-handedly breathed life back into the then moribund peace and anarchist movements. The Last of the Hippies fast became PAGE COUNT the seminal text of what was then known as anarcho-punk and which 128 later contributed to the anti-globalization movement. -

THE SHAPE of JUSTICE Thumbs up to Free Snacks in Student Affairs

2017 & 2018 ABA Law Student Division Best Newspaper Award-Winner VIRGINIA LAW WEEKLY 70 1948 - 2018 A Look The Malicious Chinchilla: Part the Second.......................................2 Inside: Confirmation Stories: Hugo Black & Supreme Court Secrets..........2 Charlottesville’s Best Donuts, Reviewed by Kids.............................4 Which Fyre Fest Documentary? ......................................................7 Wednesday, 13 February 2019 The Newspaper of the University of Virginia School of Law Since 1948 Volume 71, Number 16 around north grounds THE SHAPE OF JUSTICE Thumbs up to free snacks in Student Affairs. Krasner, Others Keynote PILA Event After dropping a whopping $70 on a Barris- ter’s ticket, ANG can’t even afford groceries. Thanks, Michael Schmid ‘21 Lisa, for saving us all from Staff Editor our own poor decisions. The third annual Shaping Justice conference took place Thumbs up to February 8 and 9 at the Law free snacks in Stu- School, featuring a variety of dent Affairs. After panel discussions, workshops, dropping a whop- and a keynote address by Larry ping $70 on a Barrister’s Krasner, District Attorney for ticket, ANG can’t even af- the City of Philadelphia. The ford groceries. Thanks, event was sponsored by the Lisa, for saving us all from Public Interest Law Associa- our own poor decisions. tion, the Program in Law and Public Service, and the Mor- Thumbs down timer Caplin Public Service to classes that Center. Panel topics included still involve fights gun violence, alternatives to for seating. ANG incarceration, the affordable specifically dropped the housing crisis, and the opioid class in musical chairs for epidemic. anxiety reasons and does The opioid epidemic was a not find this fun. -

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

Issue 148.Pmd

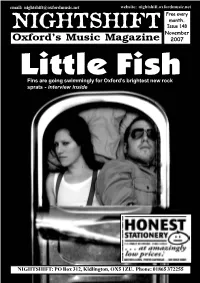

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Analiza PR Strategije I Kriznog Komuniciranja Na Primjeru Fyre Festivala

Analiza PR strategije i kriznog komuniciranja na primjeru Fyre Festivala Senjak, Antonija Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, The Faculty of Political Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet političkih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:114:101999 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FPSZG repository - master's thesis of students of political science and journalism / postgraduate specialist studies / disertations Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet političkih znanosti Diplomski studij novinarstva Antonija Senjak ANALIZA PR STRATEGIJE I KRIZNOG KOMUNICIRANJA NA PRIMJERU FYRE FESTIVALA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2020. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet političkih znanosti Diplomski studij novinarstva ANALIZA PR STRATEGIJE I KRIZNOG KOMUNICIRANJA NA PRIMJERU FYRE FESTIVALA DIPLOMSKI RAD Mentor: izv. prof.dr.sc. Domagoj Bebić Student: Antonija Senjak Zagreb Rujan, 2020. Izjava o autorstvu Izjavljujem da sam diplomski rad PR kao najmoćniji alat organizacije događaja: Analiza PR strategije i kriznog komuniciranja na primjeru Fyre Festivala, koji sam predala na ocjenu mentoru izv. prof.dr.sc. Domagoju Bebiću, napisala samostalno i da je u potpunosti riječ o mojem autorskom radu. Također, izjavljujem da dotični rad nije objavljen ni korišten u svrhe ispunjenja nastavnih obaveza na ovom ili nekom drugom učilištu te da na temelju njega nisam stekla ECTS bodove. Nadalje, izjavljujem da sam u radu poštivala etička pravila znanstvenog i akademskog rada, a posebno članke 16-19 Etičkoga kodeksa Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. Antonija Senjak ZAHVALE Od srca ponajviše hvala Petri Vulić na bezuvjetnoj podršci i pomoći u kriznim trenucima, kao i Igoru Jurilju koji je uvijek bio spreman ponuditi korisne savjete i usmjeriti me kada bih previše odlutala. -

THE BOOKSELLERS Page 2

PRESENTING PARTNER MARCH 2020 OPENING FRIDAY, MARCH 13 THE BOOKSELLERS PAGE 2 The world according to Amazon PAGE 4 A rare profile of the most-performed living composer PAGE 5 The millennial decade on screen PAGE 7 For anyone who can still “ look at a book and see a dream.– Variety” “A captivating portrait.” “Timely and essential.” “A compelling reminder of just how – Hollywood Reporter – Los Angeles Times real the news can be.” – POV The Times of Bill Cunningham Afterward This is Not a Movie Opens Friday, February 28 Opens Friday, March 13 Friday, March 27 Page 2 Page 2 Page 2 MELISSA CLARK & SAM SIFTON // DANIEL DALE ERIK LARSON // JERRY SALTZ // TANYA TALAGA PAGE 3 March 6 – 11 @HOTDOCSCINEMA /HOTDOCSCINEMA HOTDOCSCINEMA.CA 506 BLOOR STREET WEST (at Bathurst Street) 2 HOTDOCSCINEMA.CA OPENING at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema in March MEMBERS BRONZE: $8 TICKETS $13 Silver: $6 SAVE Gold: Free OPENS FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28 The Times of Bill Cunningham D: Mark Bozek | 2018 | USA | 74 min | PG Get to know iconic street photographer and fashion historian Bill Cunningham in this moving new portrait, including his four decades at The New York Times. Told in Cunningham’s own words from a recently unearthed 1994 interview, the doc chronicles the artist’s fascinating life’s story, including moonlighting as a milliner in France during the Korean War, his unique relationship with First Lady Jackie Kennedy, and his democratic view of fashion and society. Narrated by Sarah Jessica Parker, The Times of Bill Cunningham boasts an incredible archive of photographs chosen from over 3 million previously “Movingly captures unreleased images. -

MEDIA-INFO in Brief

EN MEDIA-INFO In Brief The The Street Parade has been an established cultural event for 27 years. (28th Edition) Street Parade Every year, it brings the world's best DJs, producers and musicians in the field of electronic music to Zurich. The most colourful house and techno parade in the world fascinates hundreds of thou- in brief: sands of dance fans from every continent year after year. Figures, Around 30 Love Mobiles – brightly decorated trucks carrying vast music systems, deco, DJs and Times, party people – drive at walking pace through the crowds around the lakeside in Zurich. In addi- tion to these 30 travelling stages, eight stages along the route round off the varied range of elec- Facts. tronic music available with top DJs, live acts and multimedia entertainments. As an innovative lifestyle event, the Street Parade presents innovations in the field of electronic music, fashion and digital art and has gained an international reputation as a contemporary music festival. Yet it is still a demonstration of the values of love, peace, freedom and tolerance, plus elec- tronic music. The Street Parade is an important generating force which not only triggers an en- thusiasm for this culture each year; it also provides a vital new impetus that encourages diversity in both the world of music and in the clubs. When & Where Saturday, August 10, 2019, kicking off at 1.00 pm at the Stages. Afterwards, the first Love Mobile starts at the «Utoquai»at 2.00 pm, proceeding along Lake Zurich via Bellevue, Quaibrücke and Bürkliplatz to Hafendamm Enge. -

Rave-Culture-And-Thatcherism-Sam

Altered Perspectives: UK Rave Culture, Thatcherite Hegemony and the BBC Sam Bradpiece, University of Bristol Image 1: Boys Own Magazine (London), Spring 1988 1 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………...……… 7 Chapter 1. The Rave as a Counter-Hegemonic Force: The Spatial Element…….…………….13 Chapter 2. The Rave as a Counter Hegemonic Force: Confirmation and Critique..…..…… 20 Chapter 3. The BBC and the Rave: An Agent of Moral Panic……………………………………..… 29 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 37 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 39 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 50 2 ‘You cannot break it! The bonding between the ravers is too strong! The police and councils will never tear us apart.’ In-ter-dance Magazine1 1 ‘Letters’, In-Ter-Dance (Worthing), Jul. 1993. 3 Introduction Rave culture arrived in Britain in the late 1980s, almost a decade into the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, and reached its zenith in the mid 1990s. Although academics contest the definition of the term 'rave’, Sheila Henderson’s characterization encapsulates the basic formula. She describes raves as having ‘larger than average venues’, ‘music with 120 beats per minute or more’, ‘ubiquitous drug use’, ‘distinctive dress codes’ and ‘extensive special effects’.2 Another significant ‘defining’ feature of the rave subculture was widespread consumption of the drug methylenedioxyphenethylamine (MDMA), otherwise known as Ecstasy.3 In 1996, the government suggested that over one million Ecstasy tablets were consumed every week.4 Nicholas Saunders claims that at the peak of the drug’s popularity, 10% of 16-25 year olds regularly consumed Ecstasy.5 The mass media has been instrumental in shaping popular understanding of this recent phenomenon. The ideological dominance of Thatcherism, in the 1980s and early 1990s, was reflected in the one-sided discourse presented by the British mass media. -

House, Techno & the Origins of Electronic Dance Music

HOUSE, TECHNO & THE ORIGINS OF ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC 1 EARLY HOUSE AND TECHNO ARTISTS THE STUDIO AS AN INSTRUMENT TECHNOLOGY AND ‘MISTAKES’ OR ‘MISUSE’ 2 How did we get here? disco electro-pop soul / funk Garage - NYC House - Chicago Techno - Detroit Paradise Garage - NYC Larry Levan (and Frankie Knuckles) Chicago House Music House music borrowed disco’s percussion, with the bass drum on every beat, with hi-hat 8th note offbeats on every bar and a snare marking beats 2 and 4. House musicians added synthesizer bass lines, electronic drums, electronic effects, samples from funk and pop, and vocals using reverb and delay. They balanced live instruments and singing with electronics. Like Disco, House music was “inclusive” (both socially and musically), infuenced by synthpop, rock, reggae, new wave, punk and industrial. Music made for dancing. It was not initially aimed at commercial success. The Warehouse Discotheque that opened in 1977 The Warehouse was the place to be in Chicago’s late-’70s nightlife scene. An old three-story warehouse in Chicago’s west-loop industrial area meant for only 500 patrons, the Warehouse often had over 2000 people crammed into its dark dance foor trying to hear DJ Frankie Knuckles’ magic. In 1982, management at the Warehouse doubled the admission, driving away the original crowd, as well as Knuckles. Frankie Knuckles and The Warehouse "The Godfather of House Music" Grew up in the South Bronx and worked together with his friend Larry Levan in NYC before moving to Chicago. Main DJ at “The Warehouse” until 1982 In the early 80’s, as disco was fading, he started mixing disco records with a drum machines and spacey, drawn out lines. -

Ecology Research Volume I

First Edition: 2021 ISBN: 978-93-88901-19-2 Copyright reserved by the publishers Publication, Distribution and Promotion Rights reserved by Bhumi Publishing, Nigave Khalasa, Kolhapur Despite every effort, there may still be chances for some errors and omissions to have crept in inadvertently. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. The views and results expressed in various articles are those of the authors and not of editors or publisher of the book. Published by: Bhumi Publishing, Nigave Khalasa, Kolhapur 416207, Maharashtra, India Website: www.bhumipublishing.com E-mail: [email protected] Book Available online at: https://www.bhumipublishing.com/books/ PREFACE We are delighted to publish our book entitled "Ecology Research (Volume I)". This book is the compilation of esteemed articles of acknowledged experts in the fields of ecology providing a sufficient depth of the subject to satisfy the need of a level which will be comprehensive and interesting. It is an assemblage of variety of information about advances and developments in ecology. With its application oriented and interdisciplinary approach, we hope that the students, teachers, researchers, scientists and policy makers will find this book much more useful. The articles in the book have been contributed by eminent scientists, academicians. Our special thanks and appreciation goes to experts and research workers whose contributions have enriched this book. We thank our publisher Bhumi Publishing, India for compilation of such nice data in the form of this book. Finally, we will always remain a debtor to all our well-wishers for their blessings, without which this book would not have come into existence.