Rave-Culture-And-Thatcherism-Sam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and the Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan Otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl Ld

The New Psychedelic Culture: LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and The Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl ld. by ROBERT B. MILLMAN, MD and RELATIONSHIPOFPSYCHOPATHOLOGYTOPATTERNS ANN BORDWINE BEEDER, MD OFUSE Hallucinogens and psychedelics are terms sychedelics have been used since an- and synthetic compounds primarily derived cient times in diverse cultures as an from indoles and substituted phenethylamines i/ integral part of religious or recrea- usedthat induceto describechangesbothinthethoughtnaturallyor perception.occurring tional ceremony and ritual. The rela- The most frequently used naturally occurring tionship of LSD and other psychedelics to West- substances in this class include mescaline ern culture dates from the development of the from the peyote plant, psilocybin from "magic drug in 1938 by the chemist Albert Hoffman. I mushrooms," and ayuahauscu (yag_), a root LSD and naturally occurring psychedelics such indigenous to South America. The synthetic as mescaline and psilocybin have been associ- drugs most frequently used are MDMA ('Ec- I ated in modem times with a society that re- stasy'), PCP (phencyclidine), and ketamine. jected conventional values and sought transcen- Hundreds of analogs of these compounds are dent meaning and spirituality in the use of known to exist. Some of these obscure com- drugs and the association with other users, pounds have been termed 'designer drugs? During the 1960s the psychedelics were most Perceptual distortions induced by hallu- oi%enused by individuals or small groups on an cinogen use are remarkably variable and de- intermittent basis to _celebrate' an event or to pendent on the influence of set and setting. participate in a quest for spiritual or cultural Time has been described as _standing still" by values, peoplewho spend long periodscontemplating Current use varies from the rare, perhaps perceptual, visual, or auditory stimuli. -

Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis As Evidence Erin Janssen St

St. Mary's Law Journal Volume 49 | Number 3 Article 5 6-2018 Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence Erin Janssen St. Mary's University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Evidence Commons, Internet Law Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Erin Janssen, Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence, 49 St. Mary's L.J. 699 (2018). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal/vol49/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Mary's Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Janssen: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence COMMENT HEARSAY IN THE SMILEY FACE: ANALYZING THE USE OF EMOJIS AS EVIDENCE ERIN JANSSEN* I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 700 II. Background ............................................................................................. 701 A. Federal Rules of Evidence ............................................................. 701 B. Free Speech and Technology ....................................................... -

Emoji Article

20 Headnotes l D allas B ar A s s o c iatio n A pr il 2019 Do You Speak Emoji? District of Michigan determined that uses of emojis as evidence came dur- used by the plaintiffs in emails and BY CAROL PAYNE AND TERAH MOXLEY an emoticon—a “-D,” which the court ing a 2015 trial involving Silk Road, self-assessments as evidence that the It all started with a . Throw in a viewed as a wide open-mouth smile— an online black market. In that case, plaintiffs did not subjectively believe , , , , , and a and two would- “did not materially alter the meaning the federal district judge presiding over their working conditions were abusive. be renters in Tel Aviv found themselves of a text message” included in an affi- the trial sustained an objection by the So, what does all this mean? For on the wrong side of a judgment in davit in support of a search warrant. defense after the prosecutor read text one thing, employers should have favor of a landlord who took a vacant Conversely, in a 2014 opinion from messages without mentioning smiley- strong electronic communications apartment off the market based on a Michigan appellate court, a similar face emojis contained in the messages. policies that explicitly cover symbols enthusiastic text messages he received emoticon—“:P”—sank a defamation The judge instructed the jury that it like emojis and emoticons (and even from the prospective tenants. After the case brought by a public official. In should take note of any such symbols GIFs, hashtags, and memes). -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

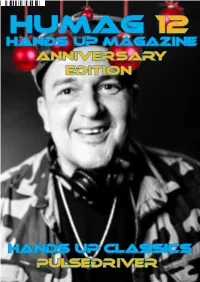

Hands up Classics Pulsedriver Hands up Magazine Anniversary Edition

HUMAG 12 Hands up Magazine anniversary Edition hANDS Up cLASSICS Pulsedriver Page 1 Welcome, The time has finally come, the 12th edition of the magazine has appeared, it took a long time and a lot has happened, but it is done. There are again specials, including an article about pulsedriver, three pages on which you can read everything that has changed at HUMAG over time and how the de- sign has changed, one page about one of the biggest hands up fans, namely Gabriel Chai from Singapo- re, who also works as a DJ, an exclusive interview with Nick Unique and at the locations an article about Der Gelber Elefant discotheque in Mühlheim an der Ruhr. For the first time, this magazine is also available for download in English from our website for our friends from Poland and Singapore and from many other countries. We keep our fingers crossed Richard Gollnik that the events will continue in 2021 and hopefully [email protected] the Easter Rave and the TechnoBase birthday will take place. Since I was really getting started again professionally and was also ill, there were unfortu- nately long delays in the publication of the magazi- ne. I apologize for this. I wish you happy reading, Have a nice Christmas and a happy new year. Your Richard Gollnik Something Christmas by Marious The new Song Christmas Time by Mariousis now available on all download portals Page 2 content Crossword puzzle What is hands up? A crossword puzzle about the An explanation from Hands hands up scene with the chan- Up. -

Electronic Dance Music

Electronic Dance Music Spring 2016 / Tuesdays 6:00 pm – 9:50 pm Taper Hall of the Humanities, 202 MUSC 410, 4.0 Units Instructor: Dr. Sean Nye Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 3–5 p.m. in 305 MUS Description: In this decade, Electronic Dance Music (EDM) has experienced an extraordinary renaissance in the United States, both in terms of music and festival culture. This development has not only surprised and fascinated the popular press, but also long-established EDM scholars and protagonists. Some have gone so far as to claim that EDM is the music of the Millennial Generation. Beyond these current developments, EDM’s history – as disco, house, techno, rave, electronica, etc. – spans a broader chronology from the 1970s to the present. It involves multiple intersections with the music and cultures of hip-hop and reggae, among others. In this course, we will examine EDM through a dual perspective emerging from our present moment: (1) the history of global EDM, especially in Europe and the United States, between the 1970s and the 2000s, and (2) current EDM scenes in Los Angeles and beyond. To address this perspective, we will carefully read from Simon Reynolds’s classic history of rave culture, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Additional readings will include selections from a newly published history of American EDM, Michaelangelo Matos’s The Underground is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America. We will also have guest speakers to discuss a range of EDM cultural practices and issues. Objectives: As a course open to non-music majors, this class will attempt to enrich our experiences and critical engagement with EDM. -

Subkulturní Rysy Na Brněnské Scéně Populární Hudby. Srovnávací Studie O Publiku Popu, Techna a Metalu

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Hudební věda Martina Marešová Subkulturní rysy na brněnské scéně populární hudby. Srovnávací studie o publiku popu, techna a metalu. Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Mikuláš Bek, Ph.D. Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ................................................................................. Podpis autora práce Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat mému vedoucímu práce doc. PhDr. Mikuláši Bekovi, Ph.D. za cenné náměty a připomínky. Dále bych chtěla poděkovat i všem ostatním, kteří mi poskytli rady a pomoc. OBSAH 1 ÚVOD ...................................................................................................................................................................................................2 2 SUBKULTURA ..................................................................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Subkultury v ................................................................................................... 4 3 POP MUSIC ................................České republice................................ a brněnská................................ scéna ........................................................................................5 3.1 ........................................................................................................ 5 4 METALStručná -

House, Techno & the Origins of Electronic Dance Music

HOUSE, TECHNO & THE ORIGINS OF ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC 1 EARLY HOUSE AND TECHNO ARTISTS THE STUDIO AS AN INSTRUMENT TECHNOLOGY AND ‘MISTAKES’ OR ‘MISUSE’ 2 How did we get here? disco electro-pop soul / funk Garage - NYC House - Chicago Techno - Detroit Paradise Garage - NYC Larry Levan (and Frankie Knuckles) Chicago House Music House music borrowed disco’s percussion, with the bass drum on every beat, with hi-hat 8th note offbeats on every bar and a snare marking beats 2 and 4. House musicians added synthesizer bass lines, electronic drums, electronic effects, samples from funk and pop, and vocals using reverb and delay. They balanced live instruments and singing with electronics. Like Disco, House music was “inclusive” (both socially and musically), infuenced by synthpop, rock, reggae, new wave, punk and industrial. Music made for dancing. It was not initially aimed at commercial success. The Warehouse Discotheque that opened in 1977 The Warehouse was the place to be in Chicago’s late-’70s nightlife scene. An old three-story warehouse in Chicago’s west-loop industrial area meant for only 500 patrons, the Warehouse often had over 2000 people crammed into its dark dance foor trying to hear DJ Frankie Knuckles’ magic. In 1982, management at the Warehouse doubled the admission, driving away the original crowd, as well as Knuckles. Frankie Knuckles and The Warehouse "The Godfather of House Music" Grew up in the South Bronx and worked together with his friend Larry Levan in NYC before moving to Chicago. Main DJ at “The Warehouse” until 1982 In the early 80’s, as disco was fading, he started mixing disco records with a drum machines and spacey, drawn out lines. -

Universidad Nacional De Quilmes Departamento De Ciencias Sociales

Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Tesis de grado Licenciatura en Historia Tesista: Ernesto Lavega Director: Hernán Thomas Techno Dance electrónico El poder del techno en los surcos del vinilo. Análisis socio-técnico de los procesos de construcción de funcionamiento del dance electrónico en Argentina entre 1988-89 y la actualidad Dedicatoria y agradecimientos: En primer lugar quiero agradecer la posibilidad de haber estudiado y arribado a esta instancia en la Universidad Pública y Gratuita. Particularmente a la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes (UNQ), al Departamento de Ciencias Sociales, la Licenciatura en Historia, la Secretaría de Extensión y la Secretaría de Investigación, por el acompañamiento, la cercanía, la organización de la carrera, las jornadas, por los incentivos a los que podemos acceder como estudiantes a través de distintas becas. A todos y todas, las y los docentes con quienes tuve la oportunidad de cursar, con los cuales pude aprender, construir conocimientos, compartir experiencias enriquecedoras y transitar este camino. Especialmente le agradezco a Hernán, por haber aceptado dirigirme en esta tarea, por sugerirme incluso que abordara el tema de investigación, y por el trabajo que finalmente realizamos, con la colaboración del equipo del Instituto de Estudios Sobre la Ciencia y la Tecnología (IESCT) de la UNQ. A mis compañeros del Instituto, con los que compartimos tantas horas, algunos viajes, relevamientos, jornadas, que colaboraron con mi trabajo y siempre, desde que ingresé con una beca allá por 2014, me hicieron sentir parte del equipo. Agradezco infinitamente y dedico este trabajo a mi familia. A mis padres por haberme apoyado con amor, en todos mis emprendimientos, por más disparatados que parecieran, desde que tengo memoria. -

On the Aesthetics of Music Video

On the Aesthetics of Music Video Christopher J ames Emmett Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. I he University of Leeds, School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. October 2002 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy lias been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Contents Acknowledgements Abstract Introduction 1: Fragments 2: Chora 3: The Technological Body Conclusion Appendix: Song Lyrics Transcription Bibliography Acknowledgements The bulk of the many thanks owed by me goes first to the University of Leeds, for the provision of a University Research Scholarship, without which I would have been unable to undertake the studies presented here, and the many library and computing facilities that have been essential to my research. A debt of gratitude is also owed to my supervisor Dr. Barbara Engh, whose encouragement and erudition, in a field of interdisciplinary research that demands a broad range of expertise, and I have frequently demanded it, has been invaluable. Mention here should also be made of Professor Adrian Rifkin, whose input at the earliest stage of my research has done much to steer the course of this work in directions that only a man of his breadth of knowledge could have imagined. Thanks also to the administrative staff of the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies, in particular Gemma Milburn, whose ever available assistance has helped to negotiate the many bureaucratic hurdles of the last four years, and kept me in constant touch with a department that has undergone considerable upheaval during recent years. -

The Holy Grail: Searching for the Perfect Accent Psychometric Testing: We Know What You Are Thinking

ČASOPIS ZA UČENJE ENGLESKOG JEZIKA magazine June / July 2012 No. 2 price 35 kn ON THE ROAD London Olympics NATIVE VIEW EXPERT VIEW The Holy Grail: Psychometric testing: searching for the we know what you are perfect accent thinking Learn more Educational, fun and interactive headlines Lecture time How to... OPENVIEW TO1 2 EDITORIAL The summer is upon us and what a summer it is set to be! The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, Euro 2012, the Olympic Games, magazine maybe the comeback of the Greek drachma, and the second is- sue of View Magazine. Let’s be honest though, the most impor- View – časopis za učenje tant event of the summer is your first appearance on the beach engleskog jezika and what to wear, and we have that covered in How To. Mihanovićeva 20, 10000 Zagreb Tel: 01 457 6639 Thank you for all your correspondence following the first issue. Fax: 01 457 6450 We really appreciate your comments and suggestions and take E-mail: [email protected] them seriously; as a result, you will find a section dedicated to Izdavač: music. We hope you enjoy it! Another new feature is the com- Lingua Media izdavaštvo d.o.o. petition page where you can win some great prizes to develop Tisak: your English further. Tiskara Velika Gorica d.o.o. Trg kralja Tomislava 38, 10410 Velika Gorica Developing and improving a language is no easy thing - there is no magic formula, no quick fix. Hard work is usually the key. Direktorica: Ivana Lieli However, reading in any language has been proven one of the [email protected] most effective ways of increasing vocabulary, improving spell- Glavni urednik: ing, and ingraining good grammar practice.