Tinker Prepdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Une Affaire De Femmes : La Chanson Comique En France

Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses E-ISSN: 1699-4949 [email protected] Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española España Marc, Isabelle Une affaire de femmes : la chanson comique en France Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses, núm. 9, abril, 2013, pp. 359-373 Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española Tenerife, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80826038021 Comment citer Numéro complet Système d'Information Scientifique Plus d'informations de cet article Réseau de revues scientifiques de l'Amérique latine, les Caraïbes, l'Espagne et le Portugal Site Web du journal dans redalyc.org Projet académique sans but lucratif, développé sous l'initiative pour l'accès ouverte ISSN: 1699-4949 nº 9, abril de 2013 Artículos Une affaire de femmes : la chanson comique en France* Isabelle Marc Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Résumé Abstract Au cours des cent dernières années, French female artists over the last century, l’humour chanté par des femmes, d’Yvette including Yvette Guibert, Brigitte Fontaine, Guibert à Brigitte Fontaine en passant par Colette Renard and Clarika, among many Colette Renard et Clarika, traverse comme others, have successfully used different forms un fil rouge l’histoire de la chanson française. of humour in their songs. This article aims to L’article a précisément pour objet d’explorer study how feminine humour is created in the les enjeux esthétiques et symboliques de la French chanson and how it evolves throughout chanson comique dans le contexte de la cons- time. Considering humour both as a means truction de l’identité féminine contempo- and as a consequence of feminine agency, it raine. -

Défigements En Chanson

Symposium international, « Bons mots, jeux de mots, jeux sur les mots : de la création à la réception », Arras, Université d'Artois, 20-21mars 2013 Bons mots, jeux de mots, jeux sur les mots. De la création à la réception , études réunies par Brigitte Buffard-Moret, 2015, Artois Presses Université, col l. « Études linguistiques » Joël JULY Université d'Aix-Marseille EA 4235, CIELAM (Centre Interdisciplinaire des Études en littérature d’Aix-Marseille) Défigements en chanson On sait que la linguistique a longtemps sous-estimé la fréquence dans la langue des procédés de figement au point qu’on rétablit aujourd’hui le déficit en posant « l’existence de deux principes opposés dans les langues : la liberté combinatoire et le figement1. » Le matériau lexical à notre disposition serait alors constitué d’unités simples que les énonciateurs associent selon les règles syntaxiques et pour une autre part d’unités complexes, de structures polylexicales qui ne s’intègrent donc pas de la même manière dans le discours et se soumettent à des restrictions combinatoires 2. Trois critères sans faille devraient permettre de les repérer au milieu d’un énoncé : opacité sémantique dans une lecture littérale3, blocage des propriétés transformationnelles, blocage des paradigmes synonymiques. Pourtant de la collocation à la phraséologie en passant par les expressions idiomatiques et la parémie, on se rend compte que bien peu d’expressions figées répondent à ces trois critères. Pour le dire rapidement et (relativement) simplement : • l’expression figée ne trouve -

Paris! Le Spectacle

Paris! Le Spectacle Saturday, November 18, 2017 at 8:00pm This is the 775th concert in Koerner Hall Anne Carrère, vocals Stéphanie Impoco, vocals Gregory Benchenafi, vocals Philippe Villa, musical direction & piano Guy Giuliano, accordion Laurent Sarrien, percussion & xylophone Fabrice Bistoni, bass Karine Soucheire, dance Jeff Dubourg, dance PROGRAM Paris medley Paris Les amants d’un jour La bohème Parisienne L'accordéoniste Yves Montand medley La foule Parlez-moi d’amour La goualante du pauvre Jean Comme d’habitude (My Way) J’ai deux amours Y’a d’la Joie medley Mon dieu INTERMISSION Moulin Rouge instrumental French Cancan medley Padam Que reste-t-il de nos amours? Charles Aznavour medley Mon amant de Saint-Jean Ne me quitte pas Jalousie Mon manège à moi Et maintenant Les petites femmes de Pigalle Milord Hymne à l’amour Non, je ne regrette rien La vie en rose Ça c’est Paris Les Champs-Élysées Musical arrangements: Gil Marsalla, Philippe Villa, Arnaud Fustélambezat This spectacular evening is a vibrant tribute to the greatest French songs of the post-war years and exports the charm and the flavour of Paris for the whole world to enjoy. The show transports us from Montmartre to the stages of the great Parisian cabarets of the time, presenting a repertoire of the greatest songs of Édith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier, Lucienne Boyer, Charles Trenet, Josephine Baker, Yves Montand, Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel, and others. Story: Françoise, a young girl who dreams of becoming a famous artist in Paris, arrives in Montmartre. On her journey, she will cross paths with Édith Piaf and become her friend, confidante, and soul mate. -

Nova Bossa Repertoire

NOVA BOSSA REPERTOIRE JOBIM / BRAZILIAN JAZZ A Felicidade Dindi Agua de Beber Girl from Ipanema Aguas de Março (Waters of March) How Insensitive Amor em Paz (Once I Loved) O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela) Bonita One Note Samba Brigas Nunca Mais Só Danço Samba Chega de Saudade Triste Corcovado (Quiet Nights) Wave Desafinado BOSSA NOVA / MPB Aquele Um - Djavan Ladeira da Preguiça - Elis Regina A Flor e o Espinho - Leny Andrade Lobo Bobo - João Gilberto Aquarela do Brasil (Brazil) - João Gilberto Maçã do Rosto - Djavan (Forró) A Rã - João Donato Mas Que Nada - Sergio Mendes Bala Com Bala - Elis Regina Maria das Mercedes - Djavan Berimbau - Baden Powell O Bêbado e a Equilibrista - Elis Regina Capim - Djavan O Mestre Sala dos Mares - Elis Regina Chove Chuva - Sergio Mendes O Pato - João Gilberto Casa Forte - Elis Regina (baião) Reza - Elis Regina Doralice - João Gilberto Rio - Leny Andrade É Com Esse Que Eu Vou - Elis Regina Serrado - Djavan Embola Bola - Djavan Telefone - Nara Leão Estate (Summer) - João Gilberto Tristeza - Beth Carvalho Fato Consumado - Djavan Vatapá - Rosa Passos Flor de Lis - Djavan Você Abusou JAZZ STANDARDS A Night in Tunisia Don't Get Around Much Anymore All of Me Fly Me To The Moon Almost Like Being in Love Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You As Time Goes By Green Dolphin Street Brother Can You Spare A Dime? Honeysuckle Rose Bye Bye Blackbird How High the Moon C'est Si Bon How Long Has This Been Going On? Dearly Beloved I Could Write A Book Do Nothing Til You Hear from Me I Only Have Eyes for You 1 I Remember You Save Your -

INTRODUCTION 1914-1918 La Grande Guerre En Chansons

INTRODUCTION 1914-1918 La Grande guerre en chansons C’était il y a cent ans, en 1914. Jusqu’en 1918, ces quatre années de guerre ont bouleversé le monde entier et, comme toutes les guerres provoqué des millions de morts, de nombreuses destructions, de grandes souffrances et blessures. Au cours de ces quatre années de conflit, les chansons ont été très présentes aussi bien sur le front qu’à l’arrière. Autrefois, quand tout le monde chantait, elles étaient souvent la seule chronique de la vie sociale et politique pour ceux qui ne savaient pas lire. Cette guerre, une des plus meurtrière, a inspiré beaucoup de poètes, écrivains et de chanteurs. Pour la plupart elles racontent la dure vie des tranchées, la violence vécue à la guerre, la souffrance, les blessures et la mort des soldats. D’autres montrent l’absurdité, l’injustice de la guerre, mais aussi que, si la société évolue, elle peut toujours basculer dans la barbarie et qu'il faut que les générations nouvelles en restent conscientes. Les chansons, légères ou engagées, expression de notre mémoire individuelle et collective, racontent nos petites histoires comme la Grande Histoire. JAURES 1977 Paroles et Musique de Jacques Brel Dans cette chanson, Jacques Brel rend hommage à Jean Jaurès et dénonce les conditions d’existence sordides des ouvriers au tournant du XXème siècle. Ces mêmes ouvriers qui servirent de chair à canon lors de la Grande guerre. Porte-parole de ces masses exploitées, Jaurès jouissait d’une immense popularité auprès des ouvriers. Ses prises de position pacifistes peu avant le déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale le rendirent très impopulaire auprès des nationalistes les plus virulents. -

Nilda Fernandez 15 Skunk Anansie 16 the Nits 17 SKUNK ANASIE

NUMÉRO 148 JANVIER 2010 ET AUSSI... SKUNK ANANSIE BB BRUNES VAMPIRE WEEKEND KOOL SHEN + CAHIER DVD LES OGRES DE BARBACK LE MAGAZINE DES DISQUAIRES INDÉPENDANTS RUBRIQUES Imports Albums 05 Start Top 05 BB BRUNES NEWS Festivals / Concerts 06 Jacno 06 Alain Bashung 06 KOOL SHEN The Undertones 07 Rihanna 07 CHRONIQUES Pop/Rock 18 NUMÉRO 148 JANVIER 2010 Electro 21 Rap 21 Français 22 Autres musiques 23 DVD du mois 24 DVD 26 VAMPIRE WEEKEND Livres 30 INTERVIEWS Les Ogres de Barback 08 BB Brunes 10 Kool Shen 11 Christoph Waltz 12 Vampire Weekend 14 Nilda Fernandez 15 Skunk Anansie 16 The Nits 17 SKUNK ANASIE START-UP est édité par RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF PUBLICITÉ Héléna McDouglas, Florence les Éditions PRÉLUDE ET FUGUE Melody LEBLOND Tristan THOMAS Rajon-Rocher, Bertrand Rocher. 29, rue de Châteaudun [email protected] [email protected] PHOTOGRAVURE 75308 PARIS Cedex 09 MAQUETTE RÉDACTION Express-Expansion Tél.: 01 75554344 Didier FITAN Paul Alexandre, Antoine Beretto, IMPRIMÉ EN FRANCE Fax: 0175554111 DIRECTRICE RÉGIE David Bouseul, Hervé Crespy, Maury / Issn: 1263-5855 DIRECTEUR DE PUBLICATION Véronique PICAN Laurent Denner, Hervé Éditions Prélude & Fugue Marc FEUILLÉE Guilleminot, Maxime Goguet, Illustration couverture D.R. | Janvier 2010 | Start Up 3| SELECTION IMPORT LE START TOP JANVIER 2010 RELEVÉ DES MEILLEURES VENTES CD DVD DAVE MATTHEWS BAND BON JOVI POP/ROCK DES DISQUAIRES EUROPE 2009 LIVE AT MADISON 3CD + DVD SQUARE GARDEN NOVEMBRE / EMINEM METALLICA RELAPSE - REFILL COFFRET COLLECTOR - DÉCEMBRE 2009 DELUXE 2CD LIVE MEXICO 2CD+2DVD MARY J BLIGE METALLICA VANESSA PARADIS Best of UNIVERSAL STRONGER WITH ORGULLO PASIN Y RENAUD Molly Malone.. -

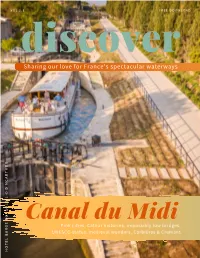

Canal Du Midi Waterways Guide

V O L 2 . 1 F R E E D O W N L O A D discover Sharing our love for France's spectacular waterways R U H T R A C M D © L I E L O S I O R Canal du Midi E G Pink cities, Cathar histories, impossibly low bridges, R A UNESCO status, medieval wonders, Corbières & Cremant B L E T O H P A G E 2 Canal du Midi YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO FRANCE'S MOST POPULAR WATERWAY Introducing the Canal du Midi Canal du Midi essentials Why visit the Canal du Midi? Where's best to stop? How to cruise the Canal du Midi? When to go? Canal du Midi top tips Contact us Travelling the magical Canal du Midi is a truly enchanting experience that will stay with you forever. It’s a journey whose every turn brings spectacular beauty that will leave you breathless. It’s an amazing feat of engineering whose elegant ingenuity will enthral you. It’s a rich and fertile region known for superb local produce, fabulous cuisine and world class wine. So, no matter how you choose to explore the Canal du Midi, by self-drive boat or hotel barge, just make sure you’re prepared to be utterly enchanted. Ruth & the team H O T E L B A R G E S A R A P H I N A P A G E 3 INTRODUCING THE CANAL DU MIDI The Canal du Midi runs from the city of Toulouse to It was the Romans who first dreamt of connecting the Mediterranean town of Sète 240km away. -

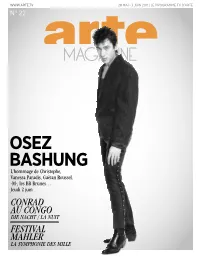

Osez Bashung

WWW.Arte.tv 28 MAI › 3 JUIN 2011 | LE PROGRAMME TV D’ARTE N° 22 OSEZ BASHUNG L’hommage de Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, Gaëtan Roussel, -M-, les BB Brunes… Jeudi 2 juin CONRAD AU CONGO DIE NacHT / LA NUIT FESTIVAL MAHLER LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE ARTE LIVE WEB ARTE LIVE WEB PARTENAIRE DU FESTIVAL DE FÈS MUSIQUES SaCRÉES DU MONDE DU 3 AU 12 JUIN 2011 Ben Harper, Youssou Ndour, Abd Al Malik, Maria Bethânia... Retrouvez les concerts sur arteliveweb.com LES GRANDS RENDEZ-VOUS SAMEDI 28 MAI › VENDREDI 3 JUIN 2011 “Ainsi pénétrions- nous plus avant chaque jour au cœur des ténèbres.” Joseph Conrad dans Die Nacht / La Nuit, mardi 31 mai à 0.50 Lire pages 6-7 et 19 SOULOY / GAMMA BASHUNG Une évocation inspirée du chanteur de “La nuit je mens”, à travers les voix de l’album hommage Tels - Alain Bashung : Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, -M-, Gaëtan Roussel, les BB Brunes... Jeudi 2 juin à 22.20 Lire pages 4-5 et 23 LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE DIRIGÉE PAR RICCARDO CHAILLY Pour le concert de clôture du Festival Mahler de Leipzig, Riccardo Chailly ILS SE MARIÈRENT dirige la Symphonie n° 8 du composi- PATHÉ teur disparu il y a tout juste cent ans. ET EURENT BEAUCOUP Dimanche 29 mai à 18.15 Lire page 12 D’ENFANTS La crise de la quarantaine perturbe le quotidien de Vin- cent et Gabrielle, tout comme celui de leurs amis. Une comédie d’Yvan Attal drôle et touchante qui vous cueille sans prévenir. Avec Charlotte Gainsbourg, lumineuse. Jeudi 2 juin à 20.40 Lire page 22 N° 22 – Semaine du 28 mai au 3 juin 2011 – ARTE Magazine 3 EN COUVErtURE ARÈME C UDOVIC L BASHUNG PAR LES BB BRUNES C’est l’une des plus belles promesses de la scène rock française. -

Affectation Des Entrants Aix Marseille Amiens

▼ AFFECTATION DES ENTRANTS AIX MARSEILLE ADAMEK,Michel ADCG Clg P. Gauthier - CAVAILLON LC AIELLO,Jean-Pierre ADLY Lyc Jean Lurçat - MARTIGUES LC ANDRIE,Stéphane ADCG Clg A. Daudet - ISTRES LC BARE,Stéphane ADCG Clg Roquecoquille - CHATEAURENARD LC BENSALEM,Alain ADCG Clg Mallarmé - MARSEILLE LC BONNET,Philippe ADCG Clg Marseilleveyre - MARSEILLE LC BOUQUET,Valérie ADCG Clg Plan de Cuques - PLAN DE CUQUES LC BRUNDU,Eric ADCG Clg Leprince Ringuet - LA FARE LES OLIVIERS LC BRUNET,Jean Charles Dir EREA EREA - SISTERON LA CARACENA,Jean François ADCG Clg Jean Moulin - MARSEILLE FF COULON,Marie ADCG Clg Voltaire - SORGUES LC CUNY,Isabelle ADCG Clg A. Chénier - MARSEILLE LC CUVILLIER,Herve PACG Clg P. Giera - AVIGNON LC DAUFES,Catherine ADLY Lyc Lucie Aubrac - BOLLENE LC DUPERRAY,Dominique ADLP Lyc PROF. L’Estaque - MARSEILLE LC FERNANDEZ,Laurent ADCG Clg Glanum - SAINT REMY DE PROVENCE LC FONTANA,Pierre ADCG Clg Arenc Bachas - MARSEILLE LC GONTARD,Marion ADCG Clg Pays des Sorgues - LE THOR LC GRUFFAT,Jean-Christophe ADCG Clg Jacques Prévert - SAINT VICTORET LC GUEREL,Christine ADCG Clg Versailles - MARSEILLE LC HOFFMANN,Elodie ADCG Clg P. Matraja - SAUSSET LES PINS LC HUBINEAU,Nathalie ADCG Clg Amandeirets - CHATEAUNEUF MARTIGUES LC LALAIN,Peggy ADCG Clg Jean Jaurès - LA CIOTAT LC MARTINEZ,Brigitte ADCG Clg Georges Brassens - BOUC BEL AIR LC MASSON,Bernard ADCG Clg Clair Soleil - MARSEILLE LC MERSALI,Abdelmalek ADCG Clg Simone de Beauvoir - VITROLLES LC MOUNOUSSAMY,Alain ADCG Clg Manet - MARSEILLE LC MOUSSAOUI,Rania ADCG Clg Miramaris - MIRAMAS LC NAUCEL,Christian ADCG Clg Lakanal - AUBAGNE LC PANITSKAS,Irène ADCG Clg Frédéric Mistral - ARLES LC PARADO,Claude ADCG Clg Giono - ORANGE LC PELTIER,Jean-Claude ADCG Clg Gérard Philipe - AVIGNON LC RISI,Antoine ADCG Clg Louis Pasteur - ISTRES LC RUL,Michèle ADCG Clg Lou Vignares - VEDENE LC THEFAINE,Johanne ADCG Clg Anatole France - MARSEILLE LC THOMAS,Christine ADCG Clg Pythéas - MARSEILLE LC THOUVENY,Blaise ADCG Clg Louis Armand - MARSEILLE LC TRIDOT,Brigitte ADCG Clg P. -

D'eurockéennes

25 ans d’EUROCKÉENNES LE CRÉDIT AGRICOLE FRANCHE-COMTÉ NE VOUS LE DIT PAS SOUVENT : IL EST LE PARTENAIRE INCONTOURNABLE DES ÉVÉNEMENTS FRANCs-COMTOIS. IL SOUTIENT Retrouvez le Crédit Agricole Franche-Comté, une banque différente, sur : www.ca-franchecomte.fr Caisse Régionale de Crédit Agricole Mutuel de Franche-Comté - Siège social : 11, avenue Elisée Cusenier 25084 Besançon Cedex 9 -Tél. 03 81 84 81 84 - Fax 03 81 84 82 82 - www.ca-franchecomte.fr - Société coopérative à capital et personnel variables agréée en tant qu’établissement de crédit - 384 899 399 RCS Besançon - Société de courtage d’assurance immatriculée au Registre des Intermédiaires en Assurances sous le n° ORIAS 07 024 000. ÉDITO SOMMAIRE La fête • 1989 – 1992 > Naissance d’un festival > L’excellence et la tolérance, François Zimmer .......................................................p.4 > Une grosse aventure, Laurent Arnold ...................................................................p.5 continue > « Caomme un pèlerinage », Laurent Arnold ........................................................p.6 Les Eurockéennes ont 25 ans. Qui l’eut > Un air de Woodstock au pied du Ballon d’Alsace, Thierry Boillot .......................p.7 cru ? Et si aujourd’hui en 2013, un doux • 1993 – 1997 > Les Eurocks, place incontournable rêveur déposait sur la table le dossier d’un grand et beau festival de musiques > Les Eurocks, précurseurs du partenariat, Lisa Lagrange ..................................... p.8 actuelles (selon la formule consacrée), > Internet : le partenariat de -

Cultural Centre Will Host the Francofolies Festival

FRI SUN TJIBAOU 08>10 CULTURAL sept. 2017 CENTRE SAT SUN NC 1 ÈRE 09>10 FRANCOFOLIES sept. 2017 VILLAGE press release Press relations Fany Torre Tél : (+687) 74 08 06 @ : [email protected] Organisation Stéphanie Habasque-Tobie Chris Tatéossian Tél : (+687) 74 80 03 Tél : (+687) 84 37 12 @ : [email protected] @ : [email protected] MusiCAL Productions 1 ST EDITION OF THE Francofolies Festival in New Caledonia From the 8th to the 10th of September 2017, the Tjibaou Cultural Centre will host the Francofolies Festival. Three days of partying, French language music and numerous local and international artists of renown are expected. Parallel to these concerts, on Sunday, 9th and Sunday, 10th of September, the “NC 1ère Village of the Francofolies” will be dedicated to the Caledonian scene. It will also be a place where the public can meet international artists. At the Tjibaou cultural centre days of Caledonian artists or bands on stage 3 concerts 6 before the international artists NC 1ère Festival Village, with over international artists 20 local artists (music, theatre, 8 or bands 1dance, etc.) A festival rooted in the Pacific as much as in the francophone world The festival is of course linked to the famous Francofolies Festival in La Rochelle, France, but it is also strongly oriented towards the world of Oceania. The aim is to present the different cultures in the entire Pacific, including the English-speaking regions. The Francofolies New Caledonia will also present numerous groups interpreting the Kaneka, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of this style of music. -

Bashung Dandy Des Matins Blêmes

A Alain WODRASCKA K C S A R D O W n i a l A Dandy destroy du rock, Alain Bashung a créé un style nouveau qui a influencé la nouvelle scène. Avec son charisme déjanté, sa voix écorchée par les excès, ses mélodies inimitables mises en mots par les plus grands paroliers (Boris Bergman, Serge Gainsbourg, Jean Fauque...), Alain Bahung a chanté pendant trente ans la note bleue : cette note fantôme impossible à inscrire sur une partition. À travers ses nombreux standards empreints d’un rock de velours : « Gaby oh Gaby », « Vertige de l’amour », « Osez Joséphine », « Madame rêve », « Ma Petite Entreprise », « Résidents de la République »..., Bashung a prouvé qu’il savait mieux que quiconque évoquer les matins blêmes, distiller un savoureux désespoir. Préfacé par Mais avec élégance. Axel BAUER Cette élégance dont il faisait preuve, lors de sa dernière tournée, en chantant sur scène malgré la maladie. Dans ce livre illustré des superbes clichés de Pierre Terrasson – qui a suivi Bashung pendant dix ans – et de Francis Vernhet, nourri de témoignages de proches du chanteur, vous retrouverez, en images et en mots, les différentes étapes de la carrière d’Alain Bashung. Une discographie et une filmographie accompagnent cet ouvrage. Bashung ISBN 978-2-84167-661-3 e Éditions Didier CARPENTIER -:HSMIOB=[\[[VX: 28 Éditions Dandy des matins blêmes Didier DC. 2512 Photographies de couverture : Pierre Terrasson CARPENTIER Alain persiste et signe en publiant, en 1967, un nouveau disque qui contient « T’as qu’a dire yeah », « Quand un amour disparaît »... Puis un autre, qui réunit les titres « Tu es une petite enfant qui fait la belle » « Tout près de vous », « Prends un peu d’amour », « Où va le train fantôme ? », cosignés Alain Bashung/Sébastien Poitrenaud.