Robert Falcon Scott, Peter Pan and Rebecca Hunt's Everland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

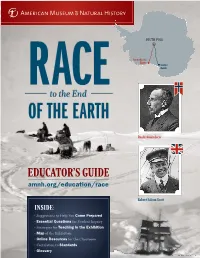

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916 ‘BLUE PLAQUES’ adorn the houses of south polar explorers James Clark Ross, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, Sir Ernest H. Shackleton, and, at one time, Captain Laurence Oates (his house was demolished and the plaque stored away). If Sir Clements Markham had not lived, it’s not unreasonable to think that of these only the one for Ross would exist today. Markham was the Britain’s great champion of polar exploration, particularly Antarctic exploration. Markham presided over the Sixth International Geographical Congress in 1895, meeting in London, and inserted the declaration that “the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken.” The world took notice and eyes were soon directed South. Markham’s great achievement was the National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery 1901-04) for which he chose Robert Falcon Scott as leader. He would have passed on both Wilson and Shackleton, too. When Scott contemplated heading South again, it was Markham who lent his expertise at planning, fundraising and ‘gentle arm-twisting.’ Without him, the British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova 1910-13) might not have been. As a young man Markham was in the Royal Navy on the Pacific station and went to the Arctic on Austin’s Franklin Search expedition of 1850-51. He served for many years in the India Office. In 1860 he was charged with collecting cinchona trees and seeds in the Andes for planting in India thus assuring a dependable supply of quinine. He accompanied Napier on the Abyssinian campaign and was present at the capture of Magdala. -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Issue 93 (June 2021, Vol.16, No.3)

The Japan Society Review 93 Book, Stage, Film, Arts and Events Review Issue 93 Volume 16 Number 3 (June 2021) The opening review of our June issue explores the Minae is a semi-autobiographical novel using fiction to fascinating life and career of Herbert Ponting, the negotiate issues of nationhood, language, and identity photographer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra between Japan and the US. The Decagon House Murders Nova expedition to the South Pole. Ponting’s travels in by Ayatsuji Yukito is a murder mystery story which follows Japan during the Meiji period are likely to be of particular the universal conventions of this classic genre, while interest to readers and resulted in several photographic bringing to it a distinctively Japanese approach. series and publications including his Japanese memoirs In This issue ends with a review of a publication on Lotus-Land Japan. Japanese wild food plants written by journalist Winifred Another captivating yet very different figure in Bird. From wild mountain and forest herbs to bamboo Japanese culture is the yamamba, the mountain witch, part and seaweed, from Kyushu to Hokkaido, this guide offers of a widely recognised “old woman in the woods” folklore. detailed information on identification, preparation and Reviewed in this issue is a new collective publication recipes to discover and taste this part of the Japanese examining the history and representations of this female natural world. character in terms of gender, art and literature among other topics. Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández Two reviews in this issue focus on literary works recently translated into English. An I-Novel by Mizumura Contents 1) Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Editor Pioneer Filmmake by Anne Strathie Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández 2) Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch Reviewers edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. -

Irony in the Novel Master Georgie Written by Beryl Bainbri–

ŽILINSKÁ UNIVERZITA V ŽILINE Fakulta prírodných vied Katedra anglického jazyka a literatúry DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCA 2006 Jana Marcinková Irony in the novel Master Georgie written by Beryl Bainbridge Diplomová práca Jana Marcinková Žilinská univerzita v Žiline Fakulta prírodných vied Vedúci diplomovej práce: doc. PhDr. Stanislav Kolá ř, CSc. Konzultant: PhDr. Gabriela Boldizsárová Komisia pre obhajoby: Katedra anglického jazyka a literatúry Stupe ň odbornej kvalifikácie: magister Dátum odovzdania práce: 2006-04-15 Žilina 2006 ČESTNÉ PREHLÁSENIE Vyhlasujem, že som túto diplomovú prácu napísala samostatne s použitím uvádzanej literatúry. Žilina 2006 POĎAKOVANIE Chcela by som sa po ďakova ť mojej konzultantke PhDr. Gabriele Boldizsárovej za jej ochotu, trpezlivos ť a usmernenie pri písaní tejto diplomovej práce. ABSTRAKT Témou tejto diplomovej práce je irónia v historickom románe „ Master Georgie “ britskej spisovate ľky Beryl Bainbridge. Formálne je rozdelená do dvoch hlavných kapitol. Prvá, teoretická čas ť, obsahuje tri podkapitoly. V prvej z nich sa zaoberáme smerom postmodernizmus a jeho vplyvom na sú časnú spolo čenskú situáciu. Sústredíme sa predovšetkým na myšlienku, že v sú časnosti už neexistuje uzavretý výklad života a celková koncepcia univerzálneho. V druhej časti je objasnený vplyv postmodernizmu na literatúru. Medzi hlavné zmeny patrí napríklad poh ľad na realitu a úloha rozpráva ča, pri čom nesmieme zabudnú ť na iróniu, ktorá predstavuje k ľúčový prvok v rámci postmoderného textu. V tretej podkapitole charakterizujeme pojem irónia a jeho rôzne formy, pri čom zis ťujeme, že v sú časnom postmodernom období je použitie irónie mnohonásobné, či už v rámci textu, alebo re či. Druhá, praktická čas ť sa zaoberá analýzou novely „ Master Georgie “ z poh ľadu irónie. -

Venture 2 Great Lives Video Worksheet Robert Falcon Scott

Venture 2 Great Lives Video worksheet Robert Falcon Scott Getting started 3 Complete the sentences with the names below. What do you know about the North and the Antarctic Scotland Royal Navy South Poles? Answer the questions: Shackleton South Africa Amundsen • Which pole is in the Arctic and which is in the 1 Scott was an officer in the . Antarctic? 2 The Discovery was built in . • What are the poles like? 3 Ernest was another famous explorer on • Have explorers been to both poles? When? Scott’s first expedition. Competences 4 The Discovery sailed south via . Check 5 Roald was the first person to reach the South Pole. 1 VIDEO Watch the video and choose the correct 6 Scott is known in the UK as ‘Scott of ’. answer. 1 The Discovery expedition went to the Antarctic Language check in 1901 to… A help another ship. 4 Use the prompts to write third conditional sentences. B fight a war. 1 If Scott (not hear) about the expedition, he (not C study nature. go) to the Antarctic. D find the South Pole. 2 Scott (could go) to the South Pole sooner if the 2 The scientists on the Discovery expedition… weather (be) better. A never reached the Antarctic. 3 If the Discovery (not be) so strong, the ice (might B didn’t survive the terrible weather. destroy) it. C couldn’t do their experiments. 4 Scott, Wilson and Shackleton (might reach) the South Pole if the conditions (not be) so bad. D had to wait to start their experiments. 5 If they (not have) dynamite, they (not free) the 3 Scott returned to the Antarctic in 1910 and… Discovery.