Global Citizenship Education: Study of the Ideological Bases, Historical Development, International Dimension, and Values and Practices of World Scouting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

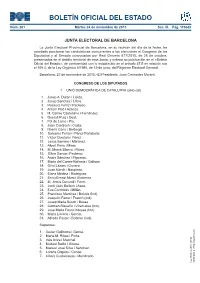

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

«Este Es Un Daño Directo Del Independentismo»

EL MUNDO. MARTES 21 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 43 ECONOMÍA i culo 155 en Cataluña es lo que ha impedido que Barcelona terminara DINERO como sede de la EMA. En un men- FRESCO saje en Twitter, calificó de «éxito del 155» que la capital catalana hubiera CARLOS sido eliminada de la carrera. Puigdemont recordó que hasta SEGOVIA el pasado 1 de octubre, fecha del referéndum ilegal, Barcelona «era España no da la favorita» para acoger este orga- nismo europeo. «Con violencia, re- una en la UE troceso democrático y el 155, el Estado la ha sentenciado», conclu- yó el ex mandatario autonómico. Los gobiernos de la UE decidieron En la misma línea se pronunció que no sólo Ámsterdam y Milán, si- el portavoz parlamentario del PDe- no incluso Copenhague –que está CAT, Carles Campuzano, quien fuera del euro– y Bratislava –cuyo afirmó que el Gobierno «no ha es- mejor aeropuerto es el de Viena– tado a la altura». eran candidatas más válidas que En un comentario publicado en Barcelona. La Ciudad Condal, que su cuenta personal de Twitter, el in- ofrecía la Torre Agbar como sede y dependentista catalán asume que el apoyo de una de las más sólidas no ganar la sede de la EMA es, «sin agencias estatales del medicamento duda, una mala noticia», si bien re- como no pasó de primera ronda, lo calca que «ni Cataluña ni Barcelo- que puede calificarse de humillación. na son quienes han fallado». A su Culpar de este fiasco totalmente al juicio, es el Gobierno quien «no ha Gobierno central como ha hecho el estado a la altura» y recuerda que ya ex presidente de la Generalitat, el Ejecutivo del PP es el principal Carles Puigdemont o parcialmente responsable ante la UE. -

Report 2015-2017

AFRICA SCOUT FOUNDATION REPORT 2015-2017 A Vision for Sustainability AFRICA SCOUT FOUNDATON © Africa Scout Foundation. August 2017 c/o World Scout Bureau, Africa Regional Office Rowallan National Scout Camp, Opp. ASK Jamhuri Showground “Gate E” P. O. Box 63070 - 00200 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: (+254 20) 245 09 85 Mobile: (+254 728) 496 553 [email protected] www.scout.org/africascoutfoundation Reproduction is authorized to Members of the Africa Scout Foundation and National Scout Organizations and Associations which are members of the World Organization of the Scout Movement. Credit for the source must be given. (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Africa Scout Foundation 01 Progress Report for the Period 2015-2017 02 Foundation Events 04 Foundation Projects 05 Challenges and Opportunities 07 Strategic Plan 2017-2022 08 Funds Summary for the Period 2015- 2017 09 Joining the Africa Scout Foundation 09 Acknowledgements 10 Contact Information 10 Appendix 1: List of Members 11 Appendix 2: Statement of Finacial Position as at 30 september 2016 15 Appendix 3: Statement of Income and Expenditure for the Year Ended 30 16 September 2016 (ii) ABOUT THE AFRICA SCOUT FOUNDATION The Africa Scout Foundation (ASF) was set up to raise funds to support the growth and development of Scouting in the Region. Over the years, its performance has not been as expected thus this year witnessed initiatives aimed at revamping the ASF to enable it better perform its core fundraising function. With the vision of “ensuring a future for Scouting in Africa” the Africa Scout Foundation aims to promote the growth of Scouting and support more young people in Africa to gain knowledge, develop skills and attitudes through quality educational programmes towards creating a better world by continuous accumulation of capital fund. -

Scout and Guide Stamps Club BULLETIN #335

Scout and Guide Stamps Club BULLETIN Volume 58 No. 3 (Whole No. 335) See article starting on page 13. MAY / JUNE 2014 1 Editorial Sorry this issue is a bit late but I gave Colin Walker extended time as he is finishing his new book on Scouting in the First World War. Since my last Editorial I have completed my last Gang Show - which went very smoothly from my point of view but I’m afraid there were a lot of complaints to the DC about my going and also the prohibiting of over 25's from appearing on stage, which he has also enforced. They are trying to put together a new team so it will be interesting to see how matters progress. I have missed out the humorous postcards from this issue as I have two interesting, but longer articles, to include. I hope that you like them. As I am typing this I have just finished watching the 70th Anniversary of D-Day events on television and the more that I watch the more that I come to admire the bravery of ordinary people - on both sides of the divide. My own father was a gunner on merchant ships during the later stages of the war (having been on a reserved occupation in the Police for the first few years). His vessel was due to be part of the first wave of the invasion and they duly left the UK loaded up with troops early on the morning of 6th June, 1944. However they only got about half way across the English Channel when the boiler on the ship failed and they then had to limp back to Portsmouth for repairs - and in the process no doubt saving a lot of lives. -

Lobatos Y Lobeznas Todos Los Derechos Reservados

Lobatos y Lobeznas Todos los derechos reservados. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser traducida o adaptada a ningún idioma, como tampoco puede ser reproducida, almacenada o transmitida en manera alguna ni por ningún medio, incluyendo las ilustraciones y el diseño de las cubiertas, sin permiso previo y por escrito de la Oficina Scout Interamericana, que representa a los titulares de la propiedad intelectual. La reserva de derechos antes mencionada rige igualmente para las asociaciones scouts nacionales miembros de la Organización Mundial del Movimiento Scout. Registro de Propiedad Intelectual: 108.700 ISBN: 956-7574-28-6 1a edición. Junio de 1999. 20.000 ejemplares 2a edición. Mayo de 2006. 5.000 ejemplares 3a edición. Marzo de 2009. 2.000 ejemplares. Oficina Scout Mundial Región Interamericana Av. Lyon 1085, 6650426 Providencia, Santiago, Chile tel. (56 2) 225 75 61 fax (56 2) 225 65 51 [email protected] www.scout.org para lobatos y lobeznas Esta es Como es pequeña, tu cartilla de la la puedes llevar etapa del lobo a todas partes Pata Tierna Ti ene espacios para escribir, dibujar y pintar Será nuestra forma de conversar ¡ Hola ! ¡ Me alegra conocerte! Yo soy Francisco, y tú...¿quién eres? Mi nombre es También me dicen Mi dirección es Teléfono Estoy en la Manada del Grupo Para que no olvides este momento en que entras a la Manada... ¡quítate el zapato y el calcetín, pinta la planta de tu pie y, antes que se seque, pisa una hoja blanca de papel! ¡Esta es mi huella! ¡Pega aquí tu huella! (si es muy grande, pega la hoja sólo por una parte y dobla el resto del papel) [ 4 ] El Pueblo Libre de los Lobos En las colinas de Seeonee, en las selvas de la India, había una manada de lobos que todos llamaban el Pueblo Libre. -

The Spanish Gay and Lesbian Movement in Comparative

Instituto Juan March Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales (CEACS) Juan March Institute Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences (CEACS) Pursuing membership in the polity : the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, 1970-1997 Author(s): Calvo, Kerman Year: 2005 Type Thesis (doctoral) University: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales, University of Essex, 2004. City: Madrid Number of pages: ix, 298 p. Abstract: El título de la tesis de Kerman Calvo Borobia es Pursuing membership in the polity: the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, (1970–1997). Lo que el estudio aborda es por qué determinados movimientos sociales varían sus estrategias ante la participación institucional. Es decir, por qué pasan de rechazar la actuación dentro del sistema político a aceptarlo. ¿Depende ello del contexto político y de cambios sociales? ¿Depende de razones debidas al propio movimiento? La explicación principal radica en las percepciones políticas y los mapas intelectuales de los activistas, en las variaciones de estas percepciones a lo largo del tiempo según distintas experiencias de socialización. Atribuye por el contrario menor importancia a las oportunidades políticas, a factores exógenos al propio movimiento, al explicar los cambios en las estrategias de éste. La tesis analiza la evolución en el movimiento de gays y de lesbianas en España desde una perspectiva comparada, a partir de su nacimiento en los años 70 hasta final del siglo, con un importante cambio hacia una estrategia de incorporación institucional a finales de los años 80. La tesis fue dirigida por la profesora Yasemin Soysal, miembro del Consejo Científico, y fue defendida en la Universidad de Essex. -

It's Not Just About Tents and Campfires

It’s not just about tents and campfires An example of how a non-governmental organization empowers young people to become good citizens making a positive change in their communities as well as in the world. Emelie Göransson Bachelor’s thesis in Development Studies, 15hp Department of Human Geography, Lund University Autumn 2013 Supervisor: Karin Steen Abstract The concept of empowerment is deeply rooted in power relations. Young people have often been seen as incompetent, however, if given the right tools they can achieve positive change today. They are not merely the adults of the future; they are the youth of today. Education and awareness rising are key ingredients in the creation of change and development. How to educate, enable and empower young people one might ask; the answer provided in this thesis is through the Scout Movement. The reason for this is that the Scout Movement is the world’s largest non-formal educational movement with a positive view on what young people can achieve. It is a movement that teaches young people good citizenship and empowers them to become self-fulfilled individuals creating a positive change in their communities. KEYWORDS: Scout, Scouting, the Scout Movement, the Scout Method, Youth, Young People, Empowerment, Citizenship, Community Involvement, Social Change. Abbreviations BSA Boy Scouts of America DDS Det Danske Spejderkorps, the Danish Guide and Scout Association MDG Millennium Development Goals NGO Non-Governmental Organization Scouterna The Guides and Scouts of Sweden UN United Nations UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WAGGGS World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts WDR World Development Report WESC World Scout Educational Congress WOSM World Organisation of the Scout Movement WTD World Thinking Day Table of contents 1 Introduction p. -

No. 28 Scoutiar.Info Scout.Org/Interamerica

EDITION No. 28 scoutiar.info scout.org/interamerica www.facebook.com/Scoutiar S EO. UB . UMBRA . FLOR Some time ago I had written on this subject. Back then I did so for Scout Magazine “Youth Forum” of the Scout Association of Mexico, AC. Now I would like to share with you this reflection using new words, as I don´t remember what I used on that occasion. When studying for the MBA , one of the professors asked us in class what does “consistency” mean to you? Several were the responses of the students in that class: to act according to what is said ... to act according to what you think ... Given these responses, that old professor said – none are accurate. Consistency means “To be oneself.” Then he explained that nature is very wise on this issue Raúl Sánchez Vaca because every being acts exactly according to what it is. The bird behaves as a bird and assumes qualities and acts as such. The same applies to the tree, the Regional Director cloud, the rock. Each has a specific function in nature. They were created for a purpose and act on a daily basis in line with the “mission” that was assigned to World Scout Bureau them by the Creator. Of course, they do not possess a will to decide whether to do so, hence “consistency” is not optional for them. Interamerican Region But if man has the option of being consistent or not it is our free will that allows us to decide. This special quality which we have means we can choose to be consistent or not. -

Download Download

The Transfer of German Pedagogy in Taiwan (1940–1970) Liou, Wei-chih ABSTRACT Wissenstransfer spielte eine zentrale Rolle im Prozess der Herausbildung akademischer Diszipli- nen bzw. der Reform der traditionellen Wissenskulturen in einer Vielzahl nichtwestlicher Länder im 20. Jahrhundert. Ein Beispiel für solch einen Modernisierungsprozess bildet der Einfluss der deutschen Bildung und Pädagogik auf Taiwan. Der Aufsatz beginnt mit einer Analyse der neun einzigen chinesischen Pädagogikstudenten, die ihre akademischen Grade in Deutschland zwi- schen 1920 und 1949 erwarben, danach nach China zurückkehrten und nach 1949 in Taiwan als „Wissensmediatoren“ fungierten. Es wird gezeigt, wie diese Pädagogen versuchten, nach dem Vorbild der geisteswissenschaftlichen Tradition der deutschen Erziehungswissenschaft die taiwanesische Pädagogik und das Bildungssystem, das bis dahin vom amerikanischen Wis- senschaftsparadigma dominiert war, zu reformieren. Dies war mit dem Anspruch verbunden, anhand der kulturellen und philosophischen Annahmen der „Kulturpädagogik“ westliche und chinesische Kultur in Taiwan miteinander harmonisch zu verbinden und angesichts der politi- schen Ereignisse in China 1949 neue Lösungen für den Bildungsbereich zu suchen. Der Analyse liegen die theoretischen Annahmen des Wissenstransfers von Steiner-Khamsi und Schriewer zugrunde. Knowledge transfer played a crucial role in the process of modernizing academic dis- ciplines in many non-Western countries during the 20th century. Many of them began either to modify the old or to establish an entirely new tradition of academic disciplines; this essay will address the specific case of pedagogy in China and Taiwan.1 Its analysis Due to the specific historical context in China and Taiwan, the transfer of Germany pedagogy in this article was researched geographically in China before 949, and after 949 in Taiwan. -

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos Polvos Trajeron Estos Lodos. Diálogos Postelectorales Diciembre De 2019

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos polvos trajeron estos lodos. Diálogos postelectorales Diciembre de 2019. La preocupación sobre el crecimiento de Vox dio lugar a un diálogo, a vuelapluma y poco sistemático, entre Julio Loras, biólogo y Alber Fabà, sociolingüista. Esas reflexiones se publicaron en Pensamiento crítico en su edición de enero. Ahora siguen dialogando, pero en este caso sobre el resultado de las últimas elecciones generales, la reacción en Catalunya a la sentencia del procés o la posibilidad de un gobierno de coalición que, en el momento en que se han redactado estas notas, aún no ha cuajado, a consecuencia de las dudas sobre la abstención (o no) de ERC en la investidura. ALBERT. Durante los últimos meses me acuerdo a menudo de Borgen, la serie de ficción en la cual tiene un notable protagonismo Kasper Juul, responsable de prensa de Birgitte Nyborg, primera ministra de Dinamarca. ¿Conoces la saga? JULIO. Hace mucho tiempo que no veo ni cine ni series. Llegaron a aburrirme. Por lo general, veía desde el principio por dónde iban a ir los tiros y perdían todo aliciente para mí. Aunque tengo algo de idea sobre esa serie por los medios. Creo que va de asesores de los políticos. ¿No es así? A. Exacto. Me viene al pelo, por eso del papel que parece que ha tenido Ivan Redondo en las decisiones que se han tomado en el PSOE, des de la moción de censura a Rajoy hasta ahora. Redondo es un típico asesor “profesional”. Que yo sepa, asesoró al candidato del PP en las municipales de Badalona en 2011. -

Palau De La Musica Catalana De Barcelona 36

Taula de contingut CITES 7 La Vanguardia - Catalán - 21/01/2018 "El ideal de justicia" con Javier del Pino, José Martí Gómez, José Mª Mena, José Mª Fernández Seijo y 8 Mateo Seguí que junto a Lourdes Lancho comentan la sentencia del Caso Palau que se dio a conocer .... Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 21/01/2018 Ana Pastor, Javier Maroto, Juan Carlos Girauta, Carles Campuzano, Óscar Puente, Joan Tardá y Pablo 10 Echenique debaten sobre la corrupción política que afecta a partidos como el PP o CDC. LA SEXTA - EL OBJETIVO - 21/01/2018 Javier del Pino, Quique Peinado, Antonio Castelo y David Navarro comentan en clave de humor noticias 12 de la semana: caso Palau, trama Púnica, rama valenciana de la Gürtel, etc. Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 20/01/2018 Entrevista a Mónica Oltra, vicepresidenta de la Generalitat Valenciana, para hablar de asuntos como los 13 recortes del gobierno, las pensiones, la corrupción en el PP y en la antigua Convergéncia o la .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 16 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre la corrupción política, especialmente los casos juzgados esta .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 19 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre el caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y el periodista Carlos Quílez analizan el caso de corrupción en Cataluña relacionado con el 21 caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua Convergència. -

Grupo Scout “San José Obrero” El 14 De Agosto De 1962, La Unión De

Grupo Scout “San José Obrero” El 14 de agosto de 1962, la Unión de Scout Católicos de Argentina otorgó el reconocimiento al Grupo Scout Nº 144 “San José Obrero” de la Parroquia homónima, creado por iniciativa de los dirigentes scout Héctor Minichelli y Héctor García, siendo su primer capellán el Padre Jorge Munier. De la síntesis de la historia del Grupo Scout “San José Obrero”, elaborada por el Grupo y expuesta en el Museo de José C. Paz extraemos1: “A principios de 1962, dos dirigentes del grupo Scout Nuestra Señora de Lourdes, que se habían radicado con sus familias en José C. Paz, Héctor Minichelli y Héctor García, propusieron al entonces Cura Párroco de la Iglesia San José Obrero, R. P. Julio Jurgener M.S.F., formar un grupo scout con los jóvenes de la comunidad. Fue así, que con la bendición del Padre Julio, comenzaron a invitar a los primeros niños que serían la semilla del grupo scout. Enseguida gestionaron la autorización correspondiente de las autoridades de la entonces Unión de Scouts Católicos Argentinos y obtuvieron el reconocimiento de la misma mediante resolución del 14 de marzo de 1962, de este modo el último fin de semana de ese mes realizaron la primer ceremonia de promesa scout, con los chicos que ya formaban tres patrullas, 24 jóvenes de entre 11 y 14 años. Reconocimiento de USCA (Unión Scout Católicos de Argentina) 1 Scouts de Argentina Grupo “San José Obrero”. Alberto Julio Fernández 1/11 El 22 de noviembre de 1981 se cumplieron 50 años de la inauguración de la entonces Capilla “San José” de José C.