Echidnas Factsheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

The Oldest Platypus and Its Bearing on Divergence Timing of the Platypus and Echidna Clades

The oldest platypus and its bearing on divergence timing of the platypus and echidna clades Timothy Rowe*†, Thomas H. Rich‡§, Patricia Vickers-Rich§, Mark Springer¶, and Michael O. Woodburneʈ *Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas, C1100, Austin, TX 78712; ‡Museum Victoria, PO Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia; §School of Geosciences, PO Box 28E, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia; ¶Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521; and ʈDepartment of Geology, Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Edited by David B. Wake, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved October 31, 2007 (received for review July 7, 2007) Monotremes have left a poor fossil record, and paleontology has broadly affect our understanding of early mammalian history, been virtually mute during two decades of discussion about with special implications for molecular clock estimates of basal molecular clock estimates of the timing of divergence between the divergence times. platypus and echidna clades. We describe evidence from high- Monotremata today comprises five species that form two resolution x-ray computed tomography indicating that Teinolo- distinct clades (16). The echidna clade includes one short-beaked phos, an Early Cretaceous fossil from Australia’s Flat Rocks locality species (Tachyglossus aculeatus; Australia and surrounding is- (121–112.5 Ma), lies within the crown clade Monotremata, as a lands) and three long-beaked species (Zaglossus bruijni, Z. basal platypus. Strict molecular clock estimates of the divergence bartoni, and Z. attenboroughi, all from New Guinea). The between platypus and echidnas range from 17 to 80 Ma, but platypus clade includes only Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Austra- Teinolophos suggests that the two monotreme clades were al- lia, Tasmania). -

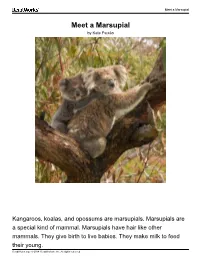

Meet a Marsupial

Meet a Marsupial Meet a Marsupial by Kate Paixão Kangaroos, koalas, and opossums are marsupials. Marsupials are a special kind of mammal. Marsupials have hair like other mammals. They give birth to live babies. They make milk to feed their young. ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Meet a Marsupial But marsupials have something that makes them different from other mammals. Female marsupials have a pouch. They use this pouch to carry their babies. Marsupial babies are called joeys. A joey stays in its mother's pouch for a long time. When it is old enough, the joey gets out and can move around on its own! ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. ReadWorks Vocabulary - mammal mammal mam·mal Definition noun 1. an animal that has hair and feeds its babies with milk from the mother. Dogs, whales, and humans are mammals. Spanish cognate mamífero: The Spanish word mamífero means mammal. These are some examples of how the word or forms of the word are used: 1. Bats are mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have hair on their bodies. 2. Whales are big ocean mammals. Mammals are animals that drink milk from their mothers. 3. The African elephant is the largest living land mammal, and the ostrich is the largest living bird. 4. The only fish Liza liked were dolphins, except her teacher told her that dolphins were mammals, not fish. 5. Every dog is a mammal. All mammals have hair on their bodies. People, horses, and elephants are also mammals. 6. The Mississippi is home to all kinds of animals. -

Cercartetus Lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae)

MAMMALIAN SPECIES 842:1–8 Cercartetus lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae) JAMIE M. HARRIS School of Environmental Science and Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, 2480, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) is a burramyid commonly called the little pygmy-possum. It is 1 of 4 species in the genus Cercartetus, which together with Burramys parvus form the marsupial family Burramyidae. This Lilliputian possum has a disjunct distribution, occurring on mainland Australia, Kangaroo Island, and in Tasmania. Mallee and heath communities are occupied in Victoria and South Australia, but in Tasmania it is found mainly in dry and wet sclerophyll forests. It is known from at least 18 fossil sites and the distribution of these reveal a significant contraction in geographic range since the late Pleistocene. Currently, this species is not listed as threatened in any state jurisdictions in Australia, but monitoring is required in order to more accurately define its conservation status. DOI: 10.1644/842.1. Key words: Australia, burramyid, hibernator, little pygmy-possum, pygmy-possum, Tasmania, Victoria mallee Published 25 September 2009 by the American Society of Mammalogists Synonymy completed 2 April 2008 www.mammalogy.org Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) Little Pygmy-possum Dromicia lepida Thomas, 1888:142. Type locality ‘‘Tasma- nia.’’ E[udromicia](Dromiciola) lepida: Matschie, 1916:260. Name combination. Eudromicia lepida Iredale and Troughton, 1934:23. Type locality ‘‘Tasmania.’’ Cercartetus lepidus: Wakefield, 1963:99. First use of current name combination. CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Diprotodontia, suborder Phalangiformes, superfamily Phalangeroidea, family Burra- myidae (Kirsch 1968). No subspecies for Cercartetus lepidus are currently recognized. -

Constituents of Platypus and Echidna Milk, with Particular Reference to the Fatty Acid Complement of the Triglycerides

Aust. J. Bioi. Sci., 1984, 37, 323-9 Constituents of Platypus and Echidna Milk, with Particular Reference to the Fatty Acid Complement of the Triglycerides Mervyn Grijfiths,A,B Brian Green,A R. M. C. Leckie,A Michael Messerc and K. W. NewgrainA A Division of Wildlife and Rangelands Research, CSIRO, P.O. Box 84, Lyneham, A.C.T. 2602. B Department of Physical Biochemistry, Australian National University, G.P.O. Box 334, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601. cDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, N.S.W. 2006. Abstract The mature milk of platypuses (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) exhibit 39· 1 gf 100 g solids, of which crude lipid accounts for 22·2% crude protein 8·2%, hexose 3·3% and sialic acid 0·43%; iron is in high concentration, 21·1 mgfl. Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) milk is more concentrated, containing 48·9% solids, with lipid. protein, hexose and sialic acid accounting for 31 ·0, 12·4, 1· 6 and O· 70% respectively; it is even richer in iron, 33·3 mgfl. The fatty acid complement of milk triglyceride from platypuses living in their natural habitat is different from that of the echidna living in the wild: platypus milk triglyceride contains 17·6% palmitic, 25 . 2% oleic and c. 30% long-chain polyunsaturated acids, whereas that of echidnas exhibits 15· 9% palmitic, 61 ·2% oleic and only c. 7% polyunsaturated acids. The fatty acid complement of echidna milk triglyceride can be changed by altering the fatty acid complement of the dietary lipid. Introduction Levels of the proximate constituents, i.e. total solids, crude lipid, crude protein, carbohydrates and minerals, were determined in samples of platypus and echidna milk. -

Short Beaked Echidna Final SAVEM

The Short-beaked ECHIDNA Bac-yard Echidna All photos: Echidna diggings in Mallee In5ured Bea- Rachel ,estcott Species The Short-bea-ed Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is a usually solitary living monotreme found in all climatic conditions in the Australian bioregion. Echidnas can swim and climb, with home ranges up to or above 250 hectares (3 . Complete AVA SA Wildlife Admission Form. Place in SAME NA3CRA9 1IS3ARDE.. Admission and smooth plastic tub at least 50 cm in height & add handling shredded paper or straw. Restrain using (1 towels/ Echidna numbers cannot be esti- gloves to lift whole animal (2 lift gently beneath mated by numbers of diggings. ventrum without gloves (3 suspend by hind feet & Echidnas can enter torpor at any limbs'this is more stressful for the animal. time of year. Echidna —trains are Examination A conscious echidna wraps into a ball when part of courtship behaviour. touched, so complete e)amination requires chemical Breeding season is between $une restraint (see below (Schultz, pers. comm. 2012 . and September. ,eigh, assess body condition, wounds, fractures, condition of spines and bea-. Cloacal temp is 2.-320 C, 1R 2110 bpm, RR 2 10/min. Se) by everting penis. Spurs on hind limbs are not confined to males. 1ealthy animals should be released as soon as possible to the location of collection. Blood Sample from cephalic, 5ugular (near thoracic inlet), femoral or brachycephalic veins. Some clinicians Collection sample from the bea- sinus, but with great care. Anesthesia & 6asting is not required, but avoid anesthesia 6at storage in Panniculus adiposus beneath immediately after eating. -

The White Ravens 2009 a Selection of International Children’S and Youth Literature and Youth a Selection of International Children’S

The White Ravens 2009 A Selection of International Children’s and Youth Literature and Youth A Selection of International Children’s Internationale Jugendbibliothek The White Ravens 2009 Symbols A Selection of International ★ Special Mention – book to which we Children’s and Youth Literature wish to draw particular attention Copyright © 2009 by Internationale Jugendbibliothek ◆ book whose content is found to con- Editor: Dr. Christiane Raabe tribute to an international understanding Editorial work: Jochen Weber Translation: Frances Bottenberg among cultures and people Copy editing: Nikola von Merveldt ● book whose text is judged to be easily understandable, i.e. easy-to-read text, Selection and texts: and yet dealing with topics of interest East-Asian Languages to older readers; well-suited to foreign- Fang Weiping and Zhao Xia (Chinese) language readers and for inclusion in Fumiko Ganzenmüller (Japanese) foreign language collections of public Gumja Stiegler-Lee (Korean) and school libraries English Claudia Söffner German Ines Galling Romance Languages Doris Amberg (Romanian) Dr. Elena Kilian (French) Antonio Leoni (Italian), with the support of Gabriele Poeschke Jochen Weber (Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, Spanish), with the support of FNLIJ (IBBY Brazil) Scandinavian Languages Dr. Andreas Bode and Ines Galling (Greenlandic, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish) Ulla Christina Schwarzelühr (Finnish) Slavic and Baltic Languages Werner Küffner (Croatian, Czech, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, Slovak), with the support of Ulla Christina Schwarzelühr (Estonian) Other Languages Doris Amberg (Hungarian) Toin Duijx (Dutch, Frisian) Eva Kaliskami and Vassiliki Nika, IBBY Greece (Greek) Lili Sadjadi-Grübel (Arabic, Persian, Turkish) The publication of this catalogue was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Youth Affairs, the Bavarian Layout: Eva Geck State Ministry for Education, and the City of Munich. -

Chapter 34: Australia, Oceania, and Antarctica Today

GeoJournal As you read this chapter, use your journal to log the key economic activities of Australia, Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World Oceania, and Antarctica. Note interesting Geography Web site at geography.glencoe.com details that illustrate the ways in which and click on Chapter Overviews—Chapter 34 to human activities and the region’s environ- preview information about the region today. ment are interrelated. Guide to Reading Living in Australia, Consider What You Know Oceania, and Environments in Australia, Oceania, and Antarctica range from tropical rain forests to icy wastelands. What Antarctica attractions or activities might draw people to visit or live in a region with such extreme differences in the physical environment? Reading Strategy A Geographic View Organizing Complete a web diagram similar to the one below by filling in Antarctic Diving the developing South Pacific countries that receive much-needed income There’s something special about from tourism. peering beneath the bottom of the world. When Antarctica’s summer diving season begins in September Developing Countries the sun has been largely absent for six months, and the water . has become as clear as any in the Read to Find Out world. Visibility is measured not in feet but in football fields. • How do people in Australia, New . Only here can you orbit an Zealand, and Oceania make their electric-blue iceberg while livings? being serenaded by the eerie View from under Antarctic ice • What role does trade play in trills of Weddell seals. the economies of South Pacific countries? —Norbert Wu, “Under Antarctic Ice,” National Geographic, February 1999 • What means of transportation and communications are used in the region? Terms to Know The wonders hidden under Antarctic ice are • station among the many attractions of Australia, Oceania, and Antarctica. -

These Animals Are Mammals Platypus and Echidna Lyle Radford Via Wikimedia Commons Radford Lyle

These Animals Are Mammals Platypus and Echidna Lyle Radford via Wikimedia Commons Radford Lyle An echidna on the move A mammal is a kind of animal. It has warm blood. It has hair. It gives birth to live babies. It feeds milk to its babies. Only two mammals lay eggs. One is the Echidna [eh-KID-nuh] and the other is the Platypus [PLAH-tuh- puss]. They both live in Australia. The echidna looks like a spiny anteater. It has a long, narrow snout. It has a long, sticky tongue that it uses to lick up ants. The echidna also has sharp spines covering its back. The spines protect it from predators. It has short legs with large claws. It uses these claws to dig up ants. It can dig very fast. 2018 Reading Is Fundamental • Content created by Simone Ribke These Animals Are Mammals The echidna is a mammal that lays eggs. It has a pouch kind of like a kangaroo. The mom lays one soft, rubbery egg. She puts it in her pouch. The egg hatches after 10 days. The baby is as big as a jellybean. It is called a puggle. The mom feeds milk to her baby. It comes from inside her pouch. The baby laps it up with its tongue. The baby grows inside the pouch. It stays there until it starts to grow spines. Then the mom takes it out. She hides it in a burrow until it grows big. By Stefan Kraft via Wikimedia Commons A platypus swimming The platypus lives near water. -

Koalas and Climate Change

KOALAS AND CLIMATE CHANGE Hungry for CO2 cuts © Daniele Sartori Summary • Increasing frequency and intensity of droughts can force Koalas to descend from trees in search of water or • Koalas are iconic animals native to Australia. They new habitats. This makes them particularly vulnerable to are true habitat and food specialists, only ever inhabiting wild and domestic predators, as well as to road traffic, forests and woodlands where Eucalyptus trees are often resulting in death. present. • Koala populations are reported to be declining • Increasing atmospheric CO levels will reduce the 2 probably due to malnutrition, the sexually-transmitted nutritional quality of Eucalyptus leaves, causing nutrient disease chlamydia, and habitat destruction. shortages in the species that forage on them. As a result, Koalas may no longer be able to meet their nutritional • Koalas have very limited capability to adapt to rapid, demands, resulting in malnutrition and starvation. human-induced climate change, making them very vulnerable to its negative impacts. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species ™ KOALAS AND CLIMATE CHANGE • Koalas are particularly vulnerable to the effects of elevated CO2 levels on plant nutritional quality, as they rely on them for food. The potential impacts of these changes on the world’s food chains are enormous. Australian icon, the Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), is a tree-dwelling marsupial found in eastern and southern Australia. Marsupials are mammals whose young are born at a very undeveloped stage before completing their development in a pouch. The Koala is not a bear, though this name has persisted outside Australia since English- speaking settlers from the late 18th century likened it to a bear. -

Australia and Oceania: Physical Geography

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Australia and Oceania: Physical Geography Encyclopedic entry. Oceania is a region made up of thousands of islands throughout the South Pacific Ocean. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Biology, Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Human Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 10 Images For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/oceania-physical-geography/ Oceania is a region made up of thousands of islands throughout the Central and South Pacific Ocean. It includes Australia, the smallest continent in terms of total land area. Most of Australia and Oceania is under the Pacific, a vast body of water that is larger than all the Earth’s continental landmasses and islands combined. The name “Oceania” justly establishes the Pacific Ocean as the defining characteristic of the continent. Oceania is dominated by the nation of Australia. The other two major landmasses of Oceania are the microcontinent of Zealandia, which includes the country of New Zealand, and the eastern half of the island of New Guinea, made up of the nation of Papua New Guinea. Oceania also includes three island regions: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (including the U.S. state of Hawaii). Oceania’s physical geography, environment and resources, and human geography can be considered separately. Oceania can be divided into three island groups: continental islands, high islands, and low islands. -

Ontogenetic Origins of Cranial Convergence Between the Extinct Marsupial Thylacine and Placental Gray Wolf ✉ ✉ Axel H

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01569-x OPEN Ontogenetic origins of cranial convergence between the extinct marsupial thylacine and placental gray wolf ✉ ✉ Axel H. Newton 1,2,3 , Vera Weisbecker 4, Andrew J. Pask2,3,5 & Christy A. Hipsley 2,3,5 1234567890():,; Phenotypic convergence, describing the independent evolution of similar characteristics, offers unique insights into how natural selection influences developmental and molecular processes to generate shared adaptations. The extinct marsupial thylacine and placental gray wolf represent one of the most extraordinary cases of convergent evolution in mammals, sharing striking cranial similarities despite 160 million years of independent evolution. We digitally reconstructed their cranial ontogeny from birth to adulthood to examine how and when convergence arises through patterns of allometry, mosaicism, modularity, and inte- gration. We find the thylacine and wolf crania develop along nearly parallel growth trajec- tories, despite lineage-specific constraints and heterochrony in timing of ossification. These constraints were found to enforce distinct cranial modularity and integration patterns during development, which were unable to explain their adult convergence. Instead, we identify a developmental origin for their convergent cranial morphologies through patterns of mosaic evolution, occurring within bone groups sharing conserved embryonic tissue origins. Inter- estingly, these patterns are accompanied by homoplasy in gene regulatory networks asso- ciated with neural crest cells, critical for skull patterning. Together, our findings establish empirical links between adaptive phenotypic and genotypic convergence and provides a digital resource for further investigations into the developmental basis of mammalian evolution. 1 School of Biomedical Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. 2 School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.