16. Ornithorhynchidae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

Miocene Mammal Reveals a Mesozoic Ghost Lineage on Insular New Zealand, Southwest Pacific

Miocene mammal reveals a Mesozoic ghost lineage on insular New Zealand, southwest Pacific Trevor H. Worthy*†, Alan J. D. Tennyson‡, Michael Archer§, Anne M. Musser¶, Suzanne J. Hand§, Craig Jonesʈ, Barry J. Douglas**, James A. McNamara††, and Robin M. D. Beck§ *School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Darling Building DP 418, Adelaide University, North Terrace, Adelaide 5005, South Australia, Australia; ‡Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, P.O. Box 467, Wellington 6015, New Zealand; §School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, New South Wales 2052, Australia; ¶Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia; ʈInstitute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, P.O. Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand; **Douglas Geological Consultants, 14 Jubilee Street, Dunedin 9011, New Zealand; and ††South Australian Museum, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia Edited by James P. Kennett, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, and approved October 11, 2006 (sent for review July 8, 2006) New Zealand (NZ) has long been upheld as the archetypical Ma) dinosaur material (13) and isolated moa bones from marine example of a land where the biota evolved without nonvolant sediments up to 2.5 Ma (1, 14), the terrestrial record older than terrestrial mammals. Their absence before human arrival is mys- 1 Ma is extremely limited. Until now, there has been no direct terious, because NZ was still attached to East Antarctica in the Early evidence for the pre-Pleistocene presence in NZ of any of its Cretaceous when a variety of terrestrial mammals occupied the endemic vertebrate lineages, particularly any group of terrestrial adjacent Australian portion of Gondwana. -

Like Globin Genes in Monotremes and Therian Mammals

Genomic evidence for independent origins of -like globin genes in monotremes and therian mammals Juan C. Opazo*, Federico G. Hoffmann, and Jay F. Storz† School of Biological Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 Edited by Morris Goodman, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, and approved December 13, 2007 (received for review November 5, 2007) Phylogenetic reconstructions of the -globin gene family in ver- embryonic -globin gene is exclusively expressed in primitive tebrates have revealed that developmentally regulated systems of erythroid cells derived from the yolk sac. However, the ‘‘- hemoglobin synthesis have been reinvented multiple times in globin’’ gene in birds is not orthologous to the -globin gene in independent lineages. For example, the functional differentiation mammals (2, 12), because they are independently derived from of embryonic and adult -like globin genes occurred independently lineage-specific duplications of a proto -globin gene. in birds and mammals. In both taxa, the embryonic -globin gene In placental mammals (subclass Eutheria), the -globin gene is exclusively expressed in primitive erythroid cells derived from cluster includes a linked set of three early expressed (prenatal) the yolk sac. However, the ‘‘-globin’’ gene in birds is not ortholo- genes, -␥-,atthe5Ј end of the cluster, and a pair of late gous to the -globin gene in mammals, because they are indepen- expressed (adult) genes, ␦ and ,atthe3Ј end. There is extensive dently derived from lineage-specific duplications of a proto variation in the copy number of these different paralogs among -globin gene. Here, we report evidence that the early and late species, and in a number of placental mammal lineages, the - expressed -like globin genes in monotremes and therian mam- and ␦-globin genes have been inactivated or deleted (13–15). -

The Oldest Platypus and Its Bearing on Divergence Timing of the Platypus and Echidna Clades

The oldest platypus and its bearing on divergence timing of the platypus and echidna clades Timothy Rowe*†, Thomas H. Rich‡§, Patricia Vickers-Rich§, Mark Springer¶, and Michael O. Woodburneʈ *Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas, C1100, Austin, TX 78712; ‡Museum Victoria, PO Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia; §School of Geosciences, PO Box 28E, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia; ¶Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521; and ʈDepartment of Geology, Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Edited by David B. Wake, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved October 31, 2007 (received for review July 7, 2007) Monotremes have left a poor fossil record, and paleontology has broadly affect our understanding of early mammalian history, been virtually mute during two decades of discussion about with special implications for molecular clock estimates of basal molecular clock estimates of the timing of divergence between the divergence times. platypus and echidna clades. We describe evidence from high- Monotremata today comprises five species that form two resolution x-ray computed tomography indicating that Teinolo- distinct clades (16). The echidna clade includes one short-beaked phos, an Early Cretaceous fossil from Australia’s Flat Rocks locality species (Tachyglossus aculeatus; Australia and surrounding is- (121–112.5 Ma), lies within the crown clade Monotremata, as a lands) and three long-beaked species (Zaglossus bruijni, Z. basal platypus. Strict molecular clock estimates of the divergence bartoni, and Z. attenboroughi, all from New Guinea). The between platypus and echidnas range from 17 to 80 Ma, but platypus clade includes only Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Austra- Teinolophos suggests that the two monotreme clades were al- lia, Tasmania). -

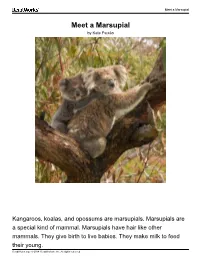

Meet a Marsupial

Meet a Marsupial Meet a Marsupial by Kate Paixão Kangaroos, koalas, and opossums are marsupials. Marsupials are a special kind of mammal. Marsupials have hair like other mammals. They give birth to live babies. They make milk to feed their young. ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Meet a Marsupial But marsupials have something that makes them different from other mammals. Female marsupials have a pouch. They use this pouch to carry their babies. Marsupial babies are called joeys. A joey stays in its mother's pouch for a long time. When it is old enough, the joey gets out and can move around on its own! ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. ReadWorks Vocabulary - mammal mammal mam·mal Definition noun 1. an animal that has hair and feeds its babies with milk from the mother. Dogs, whales, and humans are mammals. Spanish cognate mamífero: The Spanish word mamífero means mammal. These are some examples of how the word or forms of the word are used: 1. Bats are mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have hair on their bodies. 2. Whales are big ocean mammals. Mammals are animals that drink milk from their mothers. 3. The African elephant is the largest living land mammal, and the ostrich is the largest living bird. 4. The only fish Liza liked were dolphins, except her teacher told her that dolphins were mammals, not fish. 5. Every dog is a mammal. All mammals have hair on their bodies. People, horses, and elephants are also mammals. 6. The Mississippi is home to all kinds of animals. -

Cercartetus Lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae)

MAMMALIAN SPECIES 842:1–8 Cercartetus lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae) JAMIE M. HARRIS School of Environmental Science and Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, 2480, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) is a burramyid commonly called the little pygmy-possum. It is 1 of 4 species in the genus Cercartetus, which together with Burramys parvus form the marsupial family Burramyidae. This Lilliputian possum has a disjunct distribution, occurring on mainland Australia, Kangaroo Island, and in Tasmania. Mallee and heath communities are occupied in Victoria and South Australia, but in Tasmania it is found mainly in dry and wet sclerophyll forests. It is known from at least 18 fossil sites and the distribution of these reveal a significant contraction in geographic range since the late Pleistocene. Currently, this species is not listed as threatened in any state jurisdictions in Australia, but monitoring is required in order to more accurately define its conservation status. DOI: 10.1644/842.1. Key words: Australia, burramyid, hibernator, little pygmy-possum, pygmy-possum, Tasmania, Victoria mallee Published 25 September 2009 by the American Society of Mammalogists Synonymy completed 2 April 2008 www.mammalogy.org Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) Little Pygmy-possum Dromicia lepida Thomas, 1888:142. Type locality ‘‘Tasma- nia.’’ E[udromicia](Dromiciola) lepida: Matschie, 1916:260. Name combination. Eudromicia lepida Iredale and Troughton, 1934:23. Type locality ‘‘Tasmania.’’ Cercartetus lepidus: Wakefield, 1963:99. First use of current name combination. CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Diprotodontia, suborder Phalangiformes, superfamily Phalangeroidea, family Burra- myidae (Kirsch 1968). No subspecies for Cercartetus lepidus are currently recognized. -

Early Cretaceous Amphilestid ('Triconodont') Mammals from Mongolia

Early Cretaceous amphilestid ('triconodont') mammals from Mongolia ZOFIAKIELAN-JAWOROWSKA and DEMBERLYIN DASHZEVEG Kielan-Jaworowską Z. &Daslueveg, D. 1998. Early Cretaceous amphilestid (.tricono- dont') mammals from Mongotia. - Acta Pal.aeontol.ogicaPolonica,43,3, 413438. Asmall collection of ?Aptianor ?Albian amphilestid('triconodont') mammals consisting of incomplete dentaries and maxillae with teeth, from the Khoboor localiĘ Guchin Us counĘ in Mongolia, is described. Grchinodon Troftmov' 1978 is regarded a junior subjective synonym of GobiconodonTroftmov, 1978. Heavier wear of the molariforms M3 andM4than of themore anteriorone-M2 in Gobiconodonborissiaki gives indirect evidence formolariformreplacement in this taxon. The interlocking mechanismbetween lower molariforms n Gobiconodon is of the pattern seen in Kuchneotherium and Ttnodon. The ińterlocking mechanism and the type of occlusion ally Amphilestidae with Kuehneotheriidae, from which they differ in having lower molariforms with main cusps aligned and the dentary-squamosal jaw joint (double jaw joint in Kuehneotheńdae). The main cusps in upper molariforms M3-M5 of Gobiconodon, however, show incipient tńangular arrangement. The paper gives some support to Mills' idea on the therian affinities of the Amphilestidae, although it cannot be excluded that the characters that unite the two groups developed in parallel. Because of scanty material and arnbiguĘ we assign the Amphilestidae to order incertae sedis. Key words : Mammali4 .triconodonts', Amphilestidae, Kuehneotheriidae, Early Cretaceous, Mongolia. Zofia Kiel,an-Jaworowska [zkielnn@twarda,pan.pl], InsĘtut Paleobiologii PAN, ul. Twarda 5 I /5 5, PL-00-8 I 8 Warszawa, Poland. DemberĘin Dash7eveg, Geological Institute, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Introduction Beliajeva et al. (1974) reportedthe discovery of Early Cretaceous mammals at the Khoboor locality (referred to also sometimes as Khovboor), in the Guchin Us Soinon (County), Gobi Desert, Mongolia. -

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Tables, Figures and References

Samuels, Regnault & Hutchinson, PeerJ Evolution of the patellar sesamoid bone in mammals SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Tables, Figures and References Supplementary Table S1: Mammaliaform patellar status$ Inclusive clades Genus and Stratigraphic age of Patellar Comments# (partial) species (and taxon, and location(s) state reference(s) used for 0/1/2 patellar status) (absent/ ‘patelloid’/ present) Sinoconodonta Sinoconodon Jurassic, China 0 Patellar groove absent, suggests no rigneyi (Kielan- patella Jaworowska et al., 2004) Sinoconodon is included on our phylogeny within tritylodontids. Morganucodonta Megazostrodon Late Triassic, southern 0 rudnerae (Jenkins Africa & Parrington, 1976) Morganucodonta Eozostrodon sp. Late Triassic, Wales 0 Asymmetric patellar groove, (Jenkins et al., specimens disarticulated so it is hard 1976) to assess the patella but appears absent Docodonta Castorocauda 164 Mya, mid-Jurassic, 0 Semi-aquatic adaptations lutrasimilis (Ji et China al., 2006) Docodonta Agilodocodon 164 Mya, mid-Jurassic, 0 scansorius (Meng China et al., 2015) Docodonta Docofossor 160 Mya, China 0 brachydactylus (Luo et al., 2015b) Docodonta Haldanodon 150-155 Mya, Late 0 Shallow patellar groove exspectatus Jurassic, Portugal (Martin, 2005b) Australosphenida Asfaltomylos Mid-Jurassic, South ? Postcranial material absent patagonicus America (Martin, 2005a) Australosphenida Ornithorhynchus Extant 2 Platypus, genome sequenced Monotremata anatinus (Warren, Hillier, Marshall Graves et (Herzmark, 1938; al., 2008) Rowe, 1988) Australosphenida Tachyglossus -

Two New Species of Gobiconodon (Mammalia, Eutriconodonta, Gobiconodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Shahai and Fuxin Formations, Northeastern China

Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology ISSN: 0891-2963 (Print) 1029-2381 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 Two new species of Gobiconodon (Mammalia, Eutriconodonta, Gobiconodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Shahai and Fuxin formations, northeastern China Nao Kusuhashi, Yuan-Qing Wang, Chuan-Kui Li & Xun Jin To cite this article: Nao Kusuhashi, Yuan-Qing Wang, Chuan-Kui Li & Xun Jin (2016) Two new species of Gobiconodon (Mammalia, Eutriconodonta, Gobiconodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Shahai and Fuxin formations, northeastern China, Historical Biology, 28:1-2, 14-26 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2014.977881 Published online: 01 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghbi20 Download by: [University of Sussex Library] Date: 01 October 2015, At: 18:24 Historical Biology, 2016 Vol. 28, Nos. 1–2, 14–26, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2014.977881 Two new species of Gobiconodon (Mammalia, Eutriconodonta, Gobiconodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Shahai and Fuxin formations, northeastern China Nao Kusuhashia*, Yuan-Qing Wangb, Chuan-Kui Lib and Xun Jinb aDepartment of Earth’s Evolution and Environment, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Ehime University, Ehime 790-8577, Japan; bKey Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, P.R. China (Received 29 July 2014; accepted 14 October 2014) Two new gobiconodontid mammals, Gobiconodon tomidai sp. -

Constituents of Platypus and Echidna Milk, with Particular Reference to the Fatty Acid Complement of the Triglycerides

Aust. J. Bioi. Sci., 1984, 37, 323-9 Constituents of Platypus and Echidna Milk, with Particular Reference to the Fatty Acid Complement of the Triglycerides Mervyn Grijfiths,A,B Brian Green,A R. M. C. Leckie,A Michael Messerc and K. W. NewgrainA A Division of Wildlife and Rangelands Research, CSIRO, P.O. Box 84, Lyneham, A.C.T. 2602. B Department of Physical Biochemistry, Australian National University, G.P.O. Box 334, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601. cDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, N.S.W. 2006. Abstract The mature milk of platypuses (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) exhibit 39· 1 gf 100 g solids, of which crude lipid accounts for 22·2% crude protein 8·2%, hexose 3·3% and sialic acid 0·43%; iron is in high concentration, 21·1 mgfl. Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) milk is more concentrated, containing 48·9% solids, with lipid. protein, hexose and sialic acid accounting for 31 ·0, 12·4, 1· 6 and O· 70% respectively; it is even richer in iron, 33·3 mgfl. The fatty acid complement of milk triglyceride from platypuses living in their natural habitat is different from that of the echidna living in the wild: platypus milk triglyceride contains 17·6% palmitic, 25 . 2% oleic and c. 30% long-chain polyunsaturated acids, whereas that of echidnas exhibits 15· 9% palmitic, 61 ·2% oleic and only c. 7% polyunsaturated acids. The fatty acid complement of echidna milk triglyceride can be changed by altering the fatty acid complement of the dietary lipid. Introduction Levels of the proximate constituents, i.e. total solids, crude lipid, crude protein, carbohydrates and minerals, were determined in samples of platypus and echidna milk. -

Short Beaked Echidna Final SAVEM

The Short-beaked ECHIDNA Bac-yard Echidna All photos: Echidna diggings in Mallee In5ured Bea- Rachel ,estcott Species The Short-bea-ed Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is a usually solitary living monotreme found in all climatic conditions in the Australian bioregion. Echidnas can swim and climb, with home ranges up to or above 250 hectares (3 . Complete AVA SA Wildlife Admission Form. Place in SAME NA3CRA9 1IS3ARDE.. Admission and smooth plastic tub at least 50 cm in height & add handling shredded paper or straw. Restrain using (1 towels/ Echidna numbers cannot be esti- gloves to lift whole animal (2 lift gently beneath mated by numbers of diggings. ventrum without gloves (3 suspend by hind feet & Echidnas can enter torpor at any limbs'this is more stressful for the animal. time of year. Echidna —trains are Examination A conscious echidna wraps into a ball when part of courtship behaviour. touched, so complete e)amination requires chemical Breeding season is between $une restraint (see below (Schultz, pers. comm. 2012 . and September. ,eigh, assess body condition, wounds, fractures, condition of spines and bea-. Cloacal temp is 2.-320 C, 1R 2110 bpm, RR 2 10/min. Se) by everting penis. Spurs on hind limbs are not confined to males. 1ealthy animals should be released as soon as possible to the location of collection. Blood Sample from cephalic, 5ugular (near thoracic inlet), femoral or brachycephalic veins. Some clinicians Collection sample from the bea- sinus, but with great care. Anesthesia & 6asting is not required, but avoid anesthesia 6at storage in Panniculus adiposus beneath immediately after eating. -

The White Ravens 2009 a Selection of International Children’S and Youth Literature and Youth a Selection of International Children’S

The White Ravens 2009 A Selection of International Children’s and Youth Literature and Youth A Selection of International Children’s Internationale Jugendbibliothek The White Ravens 2009 Symbols A Selection of International ★ Special Mention – book to which we Children’s and Youth Literature wish to draw particular attention Copyright © 2009 by Internationale Jugendbibliothek ◆ book whose content is found to con- Editor: Dr. Christiane Raabe tribute to an international understanding Editorial work: Jochen Weber Translation: Frances Bottenberg among cultures and people Copy editing: Nikola von Merveldt ● book whose text is judged to be easily understandable, i.e. easy-to-read text, Selection and texts: and yet dealing with topics of interest East-Asian Languages to older readers; well-suited to foreign- Fang Weiping and Zhao Xia (Chinese) language readers and for inclusion in Fumiko Ganzenmüller (Japanese) foreign language collections of public Gumja Stiegler-Lee (Korean) and school libraries English Claudia Söffner German Ines Galling Romance Languages Doris Amberg (Romanian) Dr. Elena Kilian (French) Antonio Leoni (Italian), with the support of Gabriele Poeschke Jochen Weber (Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, Spanish), with the support of FNLIJ (IBBY Brazil) Scandinavian Languages Dr. Andreas Bode and Ines Galling (Greenlandic, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish) Ulla Christina Schwarzelühr (Finnish) Slavic and Baltic Languages Werner Küffner (Croatian, Czech, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, Slovak), with the support of Ulla Christina Schwarzelühr (Estonian) Other Languages Doris Amberg (Hungarian) Toin Duijx (Dutch, Frisian) Eva Kaliskami and Vassiliki Nika, IBBY Greece (Greek) Lili Sadjadi-Grübel (Arabic, Persian, Turkish) The publication of this catalogue was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Youth Affairs, the Bavarian Layout: Eva Geck State Ministry for Education, and the City of Munich.