Spain Is a Viticulture Miracle Waiting to Happen, and Has Been in This Pregnant State for Longer Than Seems Decent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents • Introduction • German Wine - fun facts • German Geography • Area Classification • Wine Production • Trends • Permitted Reds • Wine Classification • Wine Tasting • References Introduction • Our first visit to Germany was in 2000 to see our daughter who was attending college in Berlin. We rented a car and made a big loop from Frankfurt -Koblenz / Rhine - Black forest / Castles – Munich – Berlin- Frankfurt. • After college she took a job with Honeywell, moved to Germany, got married, and eventually had our first grandchild. • When we visit we always try to visit some new vineyards. • I was surprised how many good red wines were available. So with the help of friends and family we procured and carried this collection over. German Wine - fun facts • 90% of German reds are consumed in Germany. • Very few wine retailers in America have any German red wines. • Most of the largest red producers are still too small to export to USA. • You can pay $$$ for a fine French red or drink German reds for the entire year. • As vineyard owners die they split the vineyards between siblings. Some vineyards get down to 3 rows. Siblings take turns picking the center row year to year. • High quality German Riesling does not come in a blue bottle! German Geography • Germany is 138,000 sq mi or 357,000 sq km • Germany is approximately the size of Montana ( 146,000 sq mi ) • Germany is divided with respect to wine production into the following: • 13 Regions • 39 Districts • 167 Collective vineyard -

2018 Cabernet Sauvignon

2018 CABERNET SAUVIGNON Philosophy With attractive aromas of black fruit and spice, this smooth, ready-to-drink Cabernet Sauvignon is made in Paso Robles with the same care as the highest quality, traditionally crafted Bordeaux styled wines. Our grapes are hand-picked and sorted by-the-berry for consistent quality and flavor. JUSTIN Cabernet Sauvignon then spends thirteen months in traditional small oak barrels to impart depth and complexity, highlighting the exceptional balance of flavors and textures that the unique climate and soils of Paso Robles add to the classic Cabernet character in this exceptional wine. Vintage Notes The 2018 vintage started with a cool winter with only 60% of normal precipitation, most of it occurring from late February through March. Bud break began in mid to late March. May and June alternated between warm and cool temperatures during flowering, including a few windy days that naturally reduced our yields a bit. The warm weather began in June and it was hot from mid-June through the end of July with veraison starting in the last week of July. High heat continued until mid-August causing the vines to shut down slightly, delaying ripeness and maturity, but a cooling trend later in August got things back on track. The characteristic Paso warm days and cold nights in September with the help of our calcareous soils retained natural acidity in the fruit while we waited for full ripeness and maturity. The rains stayed away through October allowing us to harvest only as perfect balance of flavor and structure developed in each block of our cabernet grapes through the second week of November. -

WINE CLUB D S S E L L E O C G T I K O C N I S I Started Making Wine in 1982

c h m i d t THE GOLDMARK WINE CLUB d s S e l l e o c G t i k o c n i s I started making wine in 1982. A long time N ago now, but in those days it was very gold mark different making wines from varieties I have never made again, or in places that I never went back to. Jump over 25 years of corporate life and here I am again. Yes, we Wine Club make a lot of Cabernet and Merlot but we are making it from really unique and different places again. As I continue making wine in now 7 countries I not only look at those varieties but also varieties that are unique to the place. Carmenere or Pais in Rapel Chile, Torrontés in San Juan Argentina, and, when was the last time you had a Petite Syrah grown in Australia? Or when was the last time you tasted a wine that was crushed into a vessel and that vessel was not opened for two years? A wine club like this allows me to make the odd little gem that I enjoy doing. Whether its is a different variety, a different place or a different technique. The wines that are available here will only be available here and so I am committed to doing different things to my day job and hope that you also will experience different options than the norm. Now that you have joined Goldmark Wine Club you will be W INE MASTER traveling with me in this crazy new chmidt energized winemaking world. -

Structure in Wine Steiia Thiast

Structure in Wine steiia thiAst What is Structure? • So what is this thing, structure? It*s the sense you have that the wine has a well-established form,I think ofit as the architecture ofthe wine. A wine with a great structure will often remind me ofthe outlines of a cathedral, or the veins in a leaf...it supports, and balances the fiuit characteristics ofthe wine. The French often describe structure as the skeleton ofthe wine, as opposed to its flavor which they describe as the flesh. • Where does structure come firom? In white wines, it usually comes from alcohol or acidity; in red wines, it comes from a combination of acidity and tannin, a component in the grapes' skins and seeds. Thus, wines with a lot of tannin (like cabernet) also have a lot of structure. Beaujolais is made from gamay which does not have much tannin. As a result, Beaujolais can lack structure; it feels soft, flat or simple in the mouth (though its flavors can certainly still be attractive). • While structure is hard to articulate, you can easily taste or sense it —^and the lack of it. • Understanding structure is critical to understanding any ofthe ''powerful" red varieties: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, syrah, nebbiolo, tempranillo, and malbec, to name a few. I just don't think you can understand these wines unless you understand structure, and how it frames and focuses the powerful rush of fruit. It adds freshness, and a "lightness" to the density ofripe fiuit. Structure matters when pairing wine and food. Foods with a lot of structure themselves— like a meaty, thick steak-need wines with commensurate structure (like cabernet), or the food experience can dwarfthe wine experience. -

And Cabernet Franc Is the Star

CAN WE BE FRANC? THE HUDSON VALLEY PREPARES FOR ITS CLOSE-UP —AND CABERNET FRANC IS THE STAR. Amy Zavatto he verdant, hilly climes of the Hudson Valley are known and praised for many things. The beauty of its rolling, roiling namesake river; its famed mid-nineteenth century naturalist art movement; its acres of multi-generational fruit orchards and dairy farms; T and, lately, as the celebrated place of culinary inspiration for chefs like Dan Barber and Zak Palaccio. But while these lands, just ninety minutes shy of New York City’s northern border, can claim the country’s oldest, continually operating vineyards and oldest declared winery, the cult of wine has yet to become the calling card of the region’s lore and allure. That might be about to change. 4 HUDSON VALLEY WINE • Summer 2016 Cabernet Franc, that beautiful, black French grape variety well known for its role in both legendary Right Bank Bordeaux and Loire Valley wines, is proving to be oh-so much more than a liquidy lark here. Not only does the grape seem well at home in the Hudson Valley’s cool-climate terroir, but collective work done between the area’s grape growers, winemakers, and Cornell University have tamed many of the conundrums that once plagued producers who yearned for success with vinifera. Now, with a force borne of a few decades of trial, error, and recent promising success, Hudson Valley vintners are ready (and more than able) to stick a flag in the ground for Franc. DIGGING DOWN “I’m of Dutch-German descent; I’m not big on failure,” laughs a region express itself with the kind of purity that wins critical Doug Glorie, who with his wife and partner, MaryEllen, opened acknowledgment. -

El Territorio Que Configura La DO Montsant Resta Delimitado Por Un

DO MONTSANT Consell Regulador Plaça Quartera, 6 43730 Falset Tel. 34 977 83 17 42 · Fax: 34 977 83 06 76 · Email: [email protected] www.domontsant.com D.O. MONTSANT INFORMATION DOSSIER INTRODUCTION The D.O. Montsant (Designation of Origin or wine appellation), despite being a recently created wine appellation, has years of wine-making history to its name. Wine experts and press consider it to be an up and coming region and prestigious magazines such as “The Wine Spectator” have declared it to be “a great discovery”. The quality of Montsant wines is key to their success, as too is their great value for money. The prestigious Spanish wine guide, “Guia Peñin” agrees that “the quality of Montsant wines and their great prices make this region an excellent alternative.” In the United States, “Wine & Spirits” magazine have stated that “Montsant should be watched with interest”. Montsant wines appear in some of the most prestigious wine rankings in the World and they always tend to be the best priced amongst their rivals at the top of the list. The professionals and wineries behind the DO Montsant label are very enthusiastic. Many wineries are co-operatives with important social bases and the winemakers who make Montsant wines are often under 40 years old. We at the DO Montsant believe that youth, coupled with a solid wine-making tradition is synonymous of future, new ideas and risk-taking. To conclude, this is the DO Montsant today: a young wine appellation with a promising future ahead of it. 1 THE REGULATORY COUNCIL The wines of the DO Montsant are governed by the Regulatory council or body. -

Memoria Del Trabajo Fin De Grado

MEMORIA DEL TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO ANÁLISIS ECONÓMICO Y FINANCIERO DE LAS BODEGAS DE VINO DE LA DENOMINACIÓN DE ORIGEN DE TACORONTE-ACENTEJO ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF WINERY IN PROTECTED DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN IN TACORONTE-ACENTEJO Grado en Administración y Dirección de Empresas FACULTAD DE ECONOMÍA, EMPRESA Y TURISMO Curso Académico 2015 /2016 Autor: Dña. Bárbara María Morales Fariña Tutor: D. Juan José Díaz Hernández. San Cristóbal de La Laguna, a 3 de Marzo de 2016 1 VISTO BUENO DEL TUTOR D. Juan José Díaz Hernández del Departamento de Economía, Contabilidad y Finanzas CERTIFICA: Que la presente Memoria de Trabajo Fin de Grado en Administración y Dirección de Empresas titulada “Análisis Económico y Financiero de las bodegas de vino de la denominación de origen de Tacoronte-Acentejo” y presentada por la alumna Dña. Bárbara María Morales Fariña , realizada bajo mi dirección, reúne las condiciones exigidas por la Guía Académica de la asignatura para su defensa. Para que así conste y surta los efectos oportunos, firmo la presente en La Laguna a 3 de Marzo de dos mil dieciséis. El tutor Fdo: D. Juan José Díaz Hernández. San Cristóbal de La Laguna, a 3 de Marzo de 2016 2 ÍNDICE 1 INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………………....5 2 EL SECTOR VINÍCOLA…………………………………………………….……6 2.1 El sector vinícola en Canarias………………………………………..….6 2.2 El sector del vino en la isla de Tenerife……………………………...…..8 2.3 Las denominaciones de origen en la isla de Tenerife…………………..10 2.4 La denominación de origen de Tacoronte-Acentejo………………........12 3 ESTUDIO ECONÓMICO -

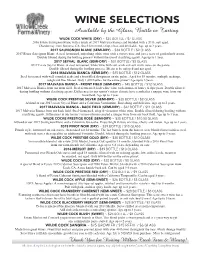

WINE SELECTIONS Available by the Glass, Bottle Or Tasting

WINE SELECTIONS Available by the Glass, Bottle or Tasting WILDE COCK WHITE (DRY) ~ $24 BOTTLE / $7 GLASS 2016 Estate Sauvignon Blanc with a touch of 2017 Malvasia Bianca and blended with a 2016, oak aged, Chardonnay from Sonoma, CA. Steel fermented, crisp, clean and drinkable. Age up to 2 years. 2017 SAUVIGNON BLANC (SEMI-DRY) ~ $34 BOTTLE / $9 GLASS 2017 Estate Sauvignon Blanc. A steel fermented, refreshing white wine with a citrusy nose and just a tease of garden herb aroma. Double filtered during the bottling process without the use of clarifying agents.Age up to 1 year. 2017 SEYVAL BLANC (SEMI-DRY) ~ $31 BOTTLE / $8 GLASS 2017 Estate Seyval Blanc. A steel fermented, white wine with soft acids and soft citrus notes on the palate. Double filtered during the bottling process. Meant to be enjoyed and not aged. 2016 MALVASIA BIANCA (SEMI-DRY) ~ $45 BOTTLE / $12 GLASS Steel fermented with well-rounded acids and a fruit filled dissipation on the palate.Aged for 10 months, multiple rackings, rough and fine filtered. Only 1,600 bottles for the entire planet!Age up to 3 years. 2017 MALVASIA BIANCA - FRONT FIELD (SEMI-DRY) ~ $45 BOTTLE / $12 GLASS 2017 Malvasia Bianca from our front field. Steel-fermented, lush white wine with aromas of honey & ripe pears. Double filtered during bottling without clarifying agents. Differences in our terroir’s micro-climate have resulted in a unique wine from our front field. Age up to 1 year. WILDE COCK PRESTIGE SILVER (SEMI-DRY) ~ $28 BOTTLE / $8 GLASS A blend of our 2017 estate Seyval Blanc and a California Vermentino. -

Custom Spanish Wine Tour Itinerary Prepared for Bryan Toy September 12Th – September 19Th, 2020

In conjunction with: Custom Spanish Wine Tour Itinerary prepared for Bryan Toy September 12th – September 19th, 2020 This is the ultimate tour to experience the best Spanish wine and food. A lifetime trip for bon vivants, foodies and wine aficionados, but also for people eager to discover the history and culture of Spain through its food and wine and its people. It includes visits to wineries in the most prestigious regions of Spanish wines, as well as an extensive introduction to the excellent Spanish gastronomy both traditional and creative and of course tapas. San Sebastian is a beautiful foodie heaven, home of the pintxos and a number of Michelin star restaurants. The tour will also take you through the history and art of Spain, from the medieval monasteries and cathedrals to the modern, cutting edge architecture of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao. We have selected unique hotels because lodging is a great part of the experience. All different, but all with the charm of unique four stars luxe selection. Highlights: Private visits in top wineries in Rioja and Priorat. Meet the winemakers and winery owners, traditional food, tapas, pintxos, Spanish wines tasting. Guggenheim Museum and Wine Culture Museum. Saturday, September 12th – Arrival into Bilbao Welcome to Spain! Upon arrival into the Bilbao Airport you will be greeted by your driver-guide and transferred to San Sebastian. Along the way, we will stop for a guided visit at the famous Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, designed by architect Frank Gehry. This unique Museum is probably one of the best modern buildings in Spain and represents architecture at its best. -

September 2000 Edition

D O C U M E N T A T I O N AUSTRIAN WINE SEPTEMBER 2000 EDITION AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT: WWW.AUSTRIAN.WINE.CO.AT DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition Foreword One of the most important responsibilities of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board is to clearly present current data concerning the wine industry. The present documentation contains not only all the currently available facts but also presents long-term developmental trends in special areas. In addition, we have compiled important background information in abbreviated form. At this point we would like to express our thanks to all the persons and authorities who have provided us with documents and personal information and thus have made an important contribution to the creation of this documentation. In particular, we have received energetic support from the men and women of the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management, the Austrian Central Statistical Office, the Chamber of Agriculture and the Economic Research Institute. This documentation was prepared by Andrea Magrutsch / Marketing Assistant Michael Thurner / Event Marketing Thomas Klinger / PR and Promotion Brigitte Pokorny / Marketing Germany Bertold Salomon / Manager 2 DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Austria – The Wine Country 1.1 Austria’s Wine-growing Areas and Regions 1.2 Grape Varieties in Austria 1.2.1 Breakdown by Area in Percentages 1.2.2 Grape Varieties – A Brief Description 1.2.3 Development of the Area under Cultivation 1.3 The Grape Varieties and Their Origins 1.4 The 1999 Vintage 1.5 Short Characterisation of the 1998-1960 Vintages 1.6 Assessment of the 1999-1990 Vintages 2. -

Wine List Bolero Winery

WINE LIST BOLERO WINERY White & Rosé Wines Glass/Bottle* Red Wines Glass/Bottle* 101 2019 Albariño 10/32 108 2017 Garnacha 12/40 102 2018 Verdelho 10/32 110 NV Poco Rojo 12/32 103 2018 Garnacha Blanca 10/29 111 2019 Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve 20/80 104 2018 Libido Blanco 10/28 115 2004 Tesoro del Sol 12/50 50% Viognier, 50% Verdelho Zinfandel Port 105 2016 Muscat Canelli 10/24 116 2017 Monastrell 14/55 107 2018 Garnacha Rosa 10/25 117 2017 Tannat 12/42 109 Bolero Cava Brut 10/34 Signature Wine Flights Let's Cool Down Talk of the Town The Gods Must be Crazy Bolero Albariño Bolero Tannat 2016 Bodegas Alto Moncayo "Aquilon" Bolero Verdelho Bolero Monastrell 2017 Bodegas El Nido "El Nido" Bolero Libido Blanco Bolero Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve 2006 Bodegas Vega Sicilia "Unico" $18 $26 $150 Bizkaiko Txakolina is a Spanish Denominación de Origen BIZKAIKO TXAKOLINA (DO) ( Jatorrizko Deitura in Basque) for wines located in the province of Bizkaia, Basque Country, Spain. The DO includes vineyards from 82 different municipalities. White Wines 1001 2019 Txomin Etzaniz, Txakolina 48 1002 2019 Antxiola Getariako, Txakolina 39 Red Wine 1011 2018 Bernabeleva 36 Rosé Wine Camino de Navaherreros 1006 2019 Antxiola Rosé, 39 Getariako Hondarrabi Beltz 1007 2019 Ameztoi Txakolina, Rubentis Rosé 49 TERRA ALTA Terra Alta is a Catalan Denominación de Origen (DO) for wines located in the west of Catalonia, Spain. As the name indicates, Terra Alta means High Land. The area is in the mountains. White Wine Red Wine 1016 2018 Edetària 38 1021 2016 Edetària 94 Via Terra, Garnatxa Blanca Le Personal Garnacha Peluda 1017 2017 Edetària Selecció, Garnatxa Blanca 64 1022 2017 "Via Edetana" 90 1018 2017 Edetària Selecció, Garnatxa Blanca (1.5ml) 135 BIERZO Bierzo is a Spanish Denominación de Origen (DO) for wines located in the northwest of the province of León (Castile and León, Spain) and covers about 3,000 km. -

Italian Wine Regions Dante Wine List

ITALIAN WINE REGIONS DANTE WINE LIST: the wine list at dante is omaha's only all italian wine list. we are also feature wines from each region of italy. each region has its own unique characteristics that make the wines & grapes distinctly unique and different from any other region of italy. as you read through our selections, you will first have our table wines, followed by wines offered by the glass & bottle, then each region with the bottle sections after that. below is a little terminology to help you with your selections: Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita or D.O.C.G. - highest quality level of wine in italy. wines produced are of the highest standards with quantiy & quality control. 74 D.O.C.G.'s exist currently. Denominazione di Origine Controllata or D.O.C. - second highest standards in italian wine making. grapes & wines are made with standards of a high level, but not as high a level as the D.O.C.G. 333 D.O.C.'s exist currently. Denominazione di Origine Protetta or D.O.P.- European Union law allows Italian producers to continue to use these terms, but the EU officially considers both to be at the same level of Protected Designation of Origin or PDO—known in Italy as Denominazione di Origine Protetta or DOP. Therefore, the DOP list below contains all 407 D.O.C.'s and D.O.C.G.'s together Indicazione Geografica Tipica or I.G.T. - wines made with non tradition grapes & methods. quality level is still high, but gives wine makers more leeway on wines that they produce.