Threat of Indian Mujahideen: the Long View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS): an Al-Qaeda Affiliate Case Study Pamela G

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS): An Al-Qaeda Affiliate Case Study Pamela G. Faber and Alexander Powell October 2017 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. SPECIFIC AUTHORITY: N00014-16-D-5003 10/27/2017 Request additional copies of this document through [email protected]. Photography Credit: Michael Markowitz, CNA. Approved by: October 2017 Dr. Jonathan Schroden, Director Center for Stability and Development Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract Section 1228 of the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) states: “The Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, shall provide for the conduct of an independent assessment of the effectiveness of the United States’ efforts to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al- Qaeda, including its affiliated groups, associated groups, and adherents since September 11, 2001.” The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict (ASD (SO/LIC)) asked CNA to conduct this independent assessment, which was completed in August 2017. In order to conduct this assessment, CNA used a comparative methodology that included eight case studies on groups affiliated or associated with Al-Qaeda. These case studies were then used as a dataset for cross-case comparison. This document is a stand-alone version of the Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) case study used in the Independent Assessment. -

Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent: a New Frontline in the Global Jihadist Movement?” the International Centre for Counter- Ter Rorism – the Hague 8, No

AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: The Nucleus of Jihad in South Asia THE SOUFAN CENTER JANUARY 2019 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA !1 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT (AQIS): The Nucleus of Jihad in South Asia THE SOUFAN CENTER JANUARY 2019 !2 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA CONTENTS List of Abbreviations 4 List of Figures & Graphs 5 Key Findings 6 Executive Summary 7 AQIS Formation: An Affiliate with Strong Alliances 11 AQIS Leadership 19 AQIS Funding & Finances 24 Wahhabization of South Asia 27 A Region Primed: Changing Dynamics in the Subcontinent 31 Global Threats Posed by AQIS 40 Conclusion 44 Contributors 46 About The Soufan Center (TSC) 48 Endnotes 49 !3 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AAI Ansar ul Islam Bangladesh ABT Ansar ul Bangla Team AFPAK Afghanistan and Pakistan Region AQC Al-Qaeda Central AQI Al-Qaeda in Iraq AQIS Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas HUJI Harkat ul Jihad e Islami HUJI-B Harkat ul Jihad e Islami Bangladesh ISI Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence ISKP Islamic State Khorasan Province JMB Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh KFR Kidnap for Randsom LeJ Lashkar e Jhangvi LeT Lashkar e Toiba TTP Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan !4 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA LIST OF FIGURES & GRAPHS Figure 1: Map of South Asia 9 Figure 2: -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent

Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent: A New Frontline in the Global Jihadist Movement? In September 2014, al-Qaeda Central (AQC) launched its latest regional affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). The new group ICCT Policy Brief was created to operate across South Asia, however, with its centre of May 2016 gravity and leadership based in Pakistan. This paper is a background brief, designed for policy makers, to shed light on and increase Author: understanding of AQC’s latest affiliate AQIS. At first glance the lack of Alastair Reed successful action has led many to argue that AQIS is of limited threat. However, despite early setbacks, the group has not been eliminated and continues to organise and plan for the future. DOI: 10.19165/2016.2.02 ISSN: 2468-0486 About the Author Alastair Reed Dr. Alastair Reed is Research Coordinator and a Research Fellow at ICCT, joining ICCT and Leiden University’s Institute of Security and Global Affairs in the autumn of 2014. Previously, he was an Assistant Professor at Utrecht University, where he completed his doctorate on research focused on understanding the processes of escalation and de-escalation in Ethnic Separatist conflicts in India and the Philippines. His main areas of interest are Terrorism and Insurgency, Conflict Analysis, Conflict Resolution, Military and Political Strategy, and International Relations, in particular with a regional focus on South Asia and South-East Asia. His current research projects address the foreign- fighter phenomenon, focusing on motivation and the use of strategic communications. About ICCT The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) is an independent think and do tank providing multidisciplinary policy advice and practical, solution-oriented implementation support on prevention and the rule of law, two vital pillars of effective counter-terrorism. -

Fragile States, Technological Capacity, and Increased Terrorist Activity Ore Korena* and Sumit Gangulya and Aashna Kahnnaa

Fragile States, Technological Capacity, and Increased Terrorist Activity Ore Korena* and Sumit Gangulya and Aashna Kahnnaa aDepartment of Poltical Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA *corresponding author: [email protected]. Fragile States, Technological Capacity, and Increased Terrorist Activity Research on terrorism disagrees on whether terrorist activity is at its highest in collapsed states, which are more hospitable to such activities, or whether terrorism increases in more capable states. We revisit this discussion by theorizing an interactive relationship: terrorists prefer to operate in politically-hospitable states, but their attack frequency within these states increases with greater technological capacity, which allows them to expand their military, recruitment, and financing operations. We analyze 27,018 terrorist incidents using regression and causal inference models, conduct a case study, and find robust support for this interactive logic. Our conclusions outline implications for policy and academic work. Keywords: terrorism; state capacity; War on Terror; technology; rogue states Does terrorist activity increase in all hospitable states equally or is it prevalent in more technologically advanced states? Recent research provides divergent answers to this question, with some studies emphasizing the role of failed states as breeding grounds for terrorists,1 while others arguing that terrorists cannot effectively operate in such states.2 Yet, to our knowledge, no study has approached this question by assuming a moderated -

India – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 24 August 2012

India – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 24 August 2012 Information on a group called Babar Khalsh: their history, aims, objectives and whether the group is political, religious, or criminal. Treatment of Babar Khalsh members by the government or society. A terrorist organisation profile published by the US government affiliated National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), in a paragraph headed “Founding Philosophy”, refers to a group called Babbar Khalsa International as follows: “Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) is an organization of Sikh separatists associated with a wave of assassinations and terrorist attacks in the 1980s. The group's primary goal is the establishment of an independent Sikh country of unspecified size in northwestern India. Group statements and media sources usually refer to this proposed state as ‘Khalistan.’” (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) (undated) Terrorist Organization Profile: Babbar Khalsa International (BKI)) A paragraph headed “Current Goals” states: “Babbar Khalsa seeks a sovereign state for Sikhs carved out of northern India. Punjab province and surrounding majority Sikh regions will serve as the basis for this state, but BKI does not articulate precise plans for the geographical, political, economic, or religious characteristics of its desired Khalistan.” (ibid) A country advice document published by the Australian Government – Refugee Review Tribunal, in a paragraph headed “Overview of the Babbar Khalsa International”, states: “The Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) is a Sikh separatist paramilitary group which has existed since the early 1980s. The BKI, like other Sikh militant groups, advocates an independent state for Sikhs, to be known as Khalistan. -

Terrorist Organisation—Lashkar-E-Tayyiba) Regulation 2015

Criminal Code (Terrorist Organisation—Lashkar-e-Tayyiba) Regulation 2015 Select Legislative Instrument No. 127, 2015 I, the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC QC, Administrator of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting with the advice of the Federal Executive Council, make the following regulation. Dated 06 August 2015 Paul de Jersey Administrator By His Excellency’s Command George Brandis QC Attorney-General OPC61401 - C Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2015L01238 Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2015L01238 Contents 1 Name ................................................................................................. 1 2 Commencement ................................................................................. 1 3 Authority ........................................................................................... 1 4 Schedules ........................................................................................... 1 5 Terrorist organisation—Lashkar-e-Tayyiba ...................................... 2 Schedule 1—Amendments 4 Criminal Code Regulations 2002 4 No. 127, 2015 Criminal Code (Terrorist Organisation—Lashkar-e-Tayyiba) i Regulation 2015 OPC61401 - C Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2015L01238 Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2015L01238 Section 1 1 Name This is the Criminal Code (Terrorist Organisation—Lashkar-e- Tayyiba) Regulation 2015. 2 Commencement (1) Each provision of this instrument specified in column 1 of the table commences, or is taken to have commenced, -

Volume XIII, Issue 5 October 2019 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 5

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume XIII, Issue 5 October 2019 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 5 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editors...............................................................................................................................1 Articles Islamist Terrorism, Diaspora Links and Casualty Rates................................................................................2 by James A. Piazza and Gary LaFree “The Khilafah’s Soldiers in Bengal”: Analysing the Islamic State Jihadists and Their Violence Justification Narratives in Bangladesh...............................................................................................................................22 by Saimum Parvez Islamic State Propaganda and Attacks: How are they Connected?..............................................................39 by Nate Rosenblatt, Charlie Winter and Rajan Basra Towards Open and Reproducible Terrorism Studies: Current Trends and Next Steps...............................61 by Sandy Schumann, Isabelle van der Vegt, Paul Gill and Bart Schuurman Taking Terrorist Accounts of their Motivations Seriously: An Exploration of the Hermeneutics of Suspicion.......................................................................................................................................................74 by Lorne L. Dawson An Evaluation of the Islamic State’s Influence over the Abu Sayyaf ...........................................................90 by Veera Singam Kalicharan Research Notes Countering Violent Extremism -

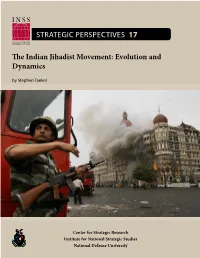

The Indian Jihadist Movement: Evolution and Dynamics by Stephen Tankel

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 17 The Indian Jihadist Movement: Evolution and Dynamics by Stephen Tankel Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified com- batant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Indian soldier takes cover as Taj Mahal Hotel burns during gun battle between Indian military and militants inside hotel, Mumbai, India, November 29, 2008 (AP Photo/David Guttenfelder, File) The Indian Jihadist Movement The Indian Jihadist Movement: Evolution and Dynamics By Stephen Tankel Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 17 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2014 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

14 Defending Mumbai from Terrorist Attack

Key Questions ▸▸ What are the most likely terrorist targets in Mumbai? ▸▸ What type of attack would the terrorists most likely mount? ▸▸ How would they gain access to the city? ▸▸ What can be done to deter future terrorist attacks? 14 Defending Mumbai from Terrorist Attack CASE NARRATIVE he teeming sprawl of modern Mumbai’s more than distribute18 million residents T had humble beginnings.1 Poised on a peninsula jutting into the Arabian Sea (see Map 14.1), the city formerly known as Bombayor began its life as a small fishing village populated by native Koli people.2 Portuguese sailors later claimed the Koli’s seven swampy islands but did not see much value in them. In 1661, the Portuguese government gifted the islands to Britain as part of the dowry for Charles II’s marriage to post,Catherine of Braganza. The city’s gradual transformation into a bustling hub of world commerce began when the East India Company recognized the potential of the location’s natural harbor and leased the islands from the British Crown. The subsequent colonization of India by Britain and the development of the textile industry in the mid-nine- teenth century solidifiedcopy, the city’s importance to Asia and the rest of the world. By 2008, Mumbai had become the epicenter of India’s booming economy. The city hosts India’s stock exchange and boasts a population density four times greaternot than that of New York City.3 A recent Global Cities Index rated Mumbai as the world’s fourth most populous city, with the twenty-fifth highest Dogross domestic product.4 Mumbai’s modern docking facilities, rail connections, and international airport make it India’s gateway to the world’s globalized economy.5 The city is also home to the popular Bollywood film industry, which churns out movies whose financial success is eclipsed only by that of their American counterparts. -

India September 2010

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT INDIA 21 SEPTEMBER 2010 UK Border Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE INDIA 21 SEPTEMBER 2010 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN INDIA FROM 17 JULY – 16 SEPTEMBER 2010 REPORTS ON INDIA PUBLISHED OR FIRST ACCESSED SINCE 16 JULY 2010 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ......................................................................................... 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.11 2. ECONOMY ............................................................................................. 2.01 3. HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3.01 Mumbai terrorist attacks, November 2008 ................................. 3.03 General Election of April-May 2009 ............................................ 3.08 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ....................................................................... 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION ...................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM ................................................................................ 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 7.01 UN Conventions ........................................................................... 7.05 8. INTERNAL SECURITY SITUATION ............................................................. 8.01 Naxalite (Maoist) -

Indian Mujahideen's ISIS Link

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 229 – 29 October 2015 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentary, Yang Razali Kassim. The Changing Jihadist Threat in India: Indian Mujahideen’s ISIS Link By Vikram Rajakumar Synopsis Indian jihadi groups, such as the Indian Mujahideen, have not pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda or ISIS. Yet many of their members have joined the ranks of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. This is a game changer to jihadism in India, and is significant to the security of the region. Commentary INDIAN JIHADI groups have long confined their activities to South Asia and refrained from participating in external conflicts. However the advent of the jihadi group ISIS’ self-styled Islamic State caliphate has changed the picture significantly. The Indian Mujahideen (IM), a militant offshoot of the Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) of about 30 members, advocates armed jihad to “liberate” India from western materialist culture and convert the entire population of India to Islam. The IM has forged ties with global terrorist groups like ISIS. The latter’s messages found resonance among members of IM, particularly IS Leader Abu Bakar Al Baghdadi’s speech, translated into Hindi, called on Indian Muslims to wage armed jihad against the oppressors.