Anxiety and Obsessive- Compulsive Disorders 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHIZOPHRENIA and OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS of EARLY ONSET Jean Starling & Isabelle Feijo

IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Chapter OTHER DISORDERS H.5 SCHIZOPHRENIA AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS OF EARLY ONSET Jean Starling & Isabelle Feijo Jean Starling FRANZCP, MPH Child and adolescent psychiatrist, Director, Walker Unit, Concord Centre for Mental Health, Sydney, and senior clinical lecturer, Discipline of Psychiatry, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Conflict of interest: none declared Isabelle Feijo FRANZCP Psychiatrist, Walker Unit, Concord Centre for Mental Health, Sydney, Australia and specialist in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy, Swiss Medical Association Conflict of interest: none declared Jackson Acknowledgement: thanks to Pollock; Polly Kwan who vetted the untitled. Cantonese websites This publication is intended for professionals training or practising in mental health and not for the general public. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or IACAPAP. This publication seeks to describe the best treatments and practices based on the scientific evidence available at the time of writing as evaluated by the authors and may change as a result of new research. Readers need to apply this knowledge to patients in accordance with the guidelines and laws of their country of practice. Some medications may not be available in some countries and readers should consult the specific drug information since not all dosages and unwanted effects are mentioned. Organizations, publications and websites are cited or linked to illustrate issues or as a source of further information. This does not mean that authors, the Editor or IACAPAP endorse their content or recommendations, which should be critically assessed by the reader. -

“What About Bob?” an Analysis of Gendered Mental Illness in a Mainstream Film Comedy

“What About Bob?” An Analysis of Gendered Mental Illness in a Mainstream Film Comedy A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the College of Graduate Studies of Northeast Ohio Medical University. Anna Plummer M.D. Medical Ethics and Humanities 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Julie Aultman (Advisor) Dr. Rachel Bracken Brian Harrell Copyright Anna Plummer 2020 ABSTRACT Mental illness has been a subject of fictional film since the early 20th century and continues to be a popular trope in mainstream movies. Portrayals of affected individuals in movies tend to be inaccurate and largely stigmatizing, negatively influencing public perception of mental illness. Recent research suggests that gender stereotypes and mental illness intersect, such that some mental illnesses are perceived as “masculine” and others as “feminine.” This notion may further stigmatize such disorders in individuals, as well as falsely inflate observed gender disparities in certain mental illnesses. Since gendered mental illness is a newly identified concept, little research has been performed exploring the way stereotypical gendered mental illness is depicted in mainstream film. This paper analyzes the movie What About Bob? to show that comedic film perpetuates stigma surrounding feminine mental illness in men and identifies the need for further study of gendered mental illness in movies to ascertain the effect such depictions have on the observed gender disparities in prevalence of certain mental disorders, as well as offers a proposal for coursework for film and medical students. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper would not have been possible without Dr. Aultman, whose teaching inspired me to pursue further education in Medical Ethics and Humanities, and whose guidance has been invaluable not only for this project, but also for addressing ethical issues in the clinic. -

White Matter Abnormalities in Adults with Bipolar Disorder Type-II

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN White matter abnormalities in adults with bipolar disorder type‑II and unipolar depression Anna Manelis1*, Adriane Soehner1, Yaroslav O. Halchenko2, Skye Satz1, Rachel Ragozzino1, Mora Lucero1, Holly A. Swartz1, Mary L. Phillips1 & Amelia Versace1 Discerning distinct neurobiological characteristics of related mood disorders such as bipolar disorder type‑II (BD‑II) and unipolar depression (UD) is challenging due to overlapping symptoms and patterns of disruption in brain regions. More than 60% of individuals with UD experience subthreshold hypomanic symptoms such as elevated mood, irritability, and increased activity. Previous studies linked bipolar disorder to widespread white matter abnormalities. However, no published work has compared white matter microstructure in individuals with BD‑II vs. UD vs. healthy controls (HC), or examined the relationship between spectrum (dimensional) measures of hypomania and white matter microstructure across those individuals. This study aimed to examine fractional anisotropy (FA), radial difusivity (RD), axial difusivity (AD), and mean difusivity (MD) across BD‑II, UD, and HC groups in the white matter tracts identifed by the XTRACT tool in FSL. Individuals with BD‑II (n = 18), UD (n = 23), and HC (n = 24) underwent Difusion Weighted Imaging. The categorical approach revealed decreased FA and increased RD in BD‑II and UD vs. HC across multiple tracts. While BD‑II had signifcantly lower FA and higher RD values than UD in the anterior part of the left arcuate fasciculus, UD had signifcantly lower FA and higher RD values than BD‑II in the area of intersections between the right arcuate, inferior fronto‑occipital and uncinate fasciculi and forceps minor. -

Included Diagnosis List

Press TAB to Diagnosis Diagnosis Description Code F20.0 Paranoid Schizophrenia F20.1 Disorganized Schizophrenia F20.2 Catatonic Schizophrenia F20.3 Undifferentiated Schizophrenia F20.5 Residual Schizophrenia F20.81 Schizophreniform Disorder F20.89 Other Schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia, Unspecified F21 Schizotypal Disorder F22 Delusional Disorder F23 Brief Psychotic Disorder F24 Shared Psychotic Disorder F25.0 Schizoaffective Disorder, Bipolar Type F25.1 Schizoaffective Disorder, Depressive Type F25.8 Other Schizoaffective Disorders F25.9 Schizoaffective Disorder, Unspecified F28 Other Psychotic Disorder Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F29 Unspecified Psychosis Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F30.10 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Unspecified F30.11 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Mild F30.12 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Moderate F30.13 Manic Episode, Severe, Without Psychotic Symptoms F30.2 Manic Episode, Severe, With Psychotic Symptoms F30.3 Manic Episode in Partial Remission F30.4 Manic Episode in Full Remission F30.8 Other Manic Episodes F30.9 Manic Episode, Unspecified F31.0 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Hypomanic F31.10 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic features, Unspecified F31.11 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Mild F31.12 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Moderate F31.13 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Severe F31.2 -

Kaplan & Sadock's Study Guide and Self Examination Review In

Kaplan & Sadock’s Study Guide and Self Examination Review in Psychiatry 8th Edition ← ↑ → © 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com 978-0-7817-8043-8 © 2007 by LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS, a WOLTERS KLUWER BUSINESS 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com “Kaplan Sadock Psychiatry” with the pyramid logo is a trademark of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. Printed in the USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sadock, Benjamin J., 1933– Kaplan & Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry / Benjamin James Sadock, Virginia Alcott Sadock. —8th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7817-8043-8 (alk. paper) 1. Psychiatry—Examinations—Study guides. 2. Psychiatry—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Sadock, Virginia A. II. Title. III. Title: Kaplan and Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. IV. Title: Study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. RC454.K36 2007 616.890076—dc22 2007010764 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. -

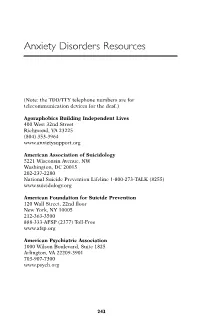

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD

Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD Thank you for being here sufferers, support, family, professionals. 2 Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD HELLO! Justin Hughes, MA, LPC Molly Martinez, PhD Owner, Dallas Counseling, PLLC Clinical Psychologist Clinician, Writer, Speaker Specialists in OCD & Anxiety Recovery (SOAR) www.justinkhughes.com www.soartogether.net Dallas, TX Richardson, TX ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD 4 Learning Objectives 1) Overview OCD and ERP 2) Identify roadblocks to effective ERP 3) Identify solutions to address these common pitfalls 5 Want these slides right now??? www.justinkhughes.com/ocd 6 PART ONE: Review The Basics You Probably Know... ● What OCD is ● What ERP is ● That ERP is the PART ONE: gold-standard of Review the evidence-based treatment Basics for OCD 8 For a PRIZE... What is the average amount of symptom reduction after a trial of ERP for OCD? 9 60-70%!! (Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2015; Foa et al., 2010) 10 You Might Know... ● Compulsions function by reducing distress via: ○ Reassurance PART ONE: ○ Avoidance Review the ● ERP is hard Basics ● ERP requires planning ● ERP requires adjustment ● ERP doesn’t always work as expected 11 PART TWO: ERP Pitfalls & Solutions ● Fear-Related Issues ○ Therapists’ Fears ○ Not Addressing the Core Fear ○ Clients’ Fear of Distress ● Covert Compulsive Behaviors ○ Reassurance ○ Mental Compulsions PART TWO: ○ Distraction ● Treatment Plan(ning) Problems ERP Pitfalls & ○ Treatment Compliance Solutions ○ Not Going Far Enough ○ Not Working with Family ○ Wrong Form of Exposure ○ Unrealistic Expectations (Extinction Burst)Medication Myths/Misconceptions ○ Detours & Comorbidities ○ Therapy “Dosing” ○ No Relapse Prevention Plan 13 Fear-Related Pitfalls & Solutions For a PRIZE.. -

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety Disorders Anxiety Disorders Overview n What is anxiety? n Categories of anxiety disorders n Generalized Anxiety Disorder n Panic Disorder n Specific Phobia/Social Phobia n Obsessive Compulsive Disorder n DSM-IV diagnoses n Treatments Anxiety n Probably experienced some of this during the exam n What does it feel like? n When is it a “disorder?” n What is the difference between fear and anxiety? n Anxiety defined as n uneasiness stemming from the anticipation of danger n Fear defined as n a reaction to a specific threat from the real, physical world 1 Anxiety n Anxiety is an evolutionary useful feeling n part of the flight or fight response n useful to have a response of energizing to get out of a situation n sometimes this gets in our way n feels not so adaptive Anxiety n Diagnosing n For a person to be diagnosed as having anxiety, the anxiety must be out of proportion to the perceived threat n The anxiety is recognized by the individual seeking treatment to be excessive or unreasonable Anxiety Disorders n Several types/different diagnoses n Based on formal (topographical) features n Should be distinct n Will see much overlap within a category (e.g. within Anxiety) n Also see overlap between other categories (e.g., OCD and eating disorders) 2 Anxiety Disorders n Six disorders: n Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) n Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) n Phobias n Panic disorder ________________________________ n Acute stress disorder n Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) GAD n One of the most -

''The Mind Is Its Own Place'': Amelioration of Claustrophobia in Semantic Dementia

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Behavioural Neurology Volume 2014, Article ID 584893, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/584893 Case Report ‘‘The Mind Is Its Own Place’’: Amelioration of Claustrophobia in Semantic Dementia Camilla N. Clark,1 Laura E. Downey,1 Hannah L. Golden,1 Phillip D. Fletcher,1 Rajith de Silva,2 Alberto Cifelli,2 and Jason D. Warren1 1 Dementia Research Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, 8-11 Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK 2 Essex Neurosciences Centre, Queen’s Hospital, Rom Valley Way, Romford RM7 0AG, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Jason D. Warren; [email protected] Received 1 March 2013; Accepted 17 June 2013; Published 6 March 2014 Academic Editor: Argye E. Hillis Copyright © 2014 Camilla N. Clark et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Phobias are among the few intensely fearful experiences we regularly have in our everyday lives, yet the brain basis of phobic responses remains incompletely understood. Here we describe the case of a 71-year-old patient with a typical clinicoanatomical syndrome of semantic dementia led by selective (predominantly right-sided) temporal lobe atrophy, who showed striking amelioration of previously disabling claustrophobia following onset of her cognitive syndrome. We interpret our patient’s newfound fearlessness as an interaction of damaged limbic and autonomic responsivity with loss of the cognitive meaning of previously threatening situations. This case has implications for our understanding of brain network disintegration in semantic dementia and the neurocognitive basis of phobias more generally. -

Psychopathology & Abnormal Psychology

PsychopathologyPsychopathology && AbnormalAbnormal PsychologyPsychology WeWe havehave talkedtalked aboutabout individualindividual differencesdifferences inin personality,personality, abilities,abilities, etc.,etc., butbut somesome individualindividual differencesdifferences gogo beyondbeyond thethe rangerange ofof normalnormal functioningfunctioning andand areare usuallyusually calledcalled psychologicalpsychological disordersdisorders JustJust howhow toto definedefine psychopathologypsychopathology isis thethe subjectsubject ofof somesome disagreementdisagreement Is it simply statistically infrequent behavior? Violation of social norms? Behavior that produces personal distress? Maladaptive or dysfunctional behavior? PsychologicalPsychological disordersdisorders generallygenerally fitfit severalseveral ofof thesethese criteriacriteria ClassificationClassification schemesschemes ThreeThree categoriescategories (up(up untiluntil aboutabout 2525 yrsyrs ago)ago) Organic brain syndromes Neurosis : any disorder characterized by conflict and anxiety that cause distress and impair a person ’s functioning but don ’t render him/her incapable of coping with external reality (e.g., phobias, panic disorder, obsessive -compulsive disorder, etc.) Psychosis : any disorder characterized by severely disordered thought or perception to the point of a break with reality (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) Examples ClassificationClassification schemesschemes TheThe currentcurrent emphasisemphasis isis onon clear,clear, observableobservable -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle. -

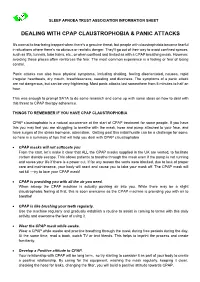

Dealing with Cpap Claustrophobia & Panic Attacks

SLEEP APNOEA TRUST ASSOCIATION INFORMATION SHEET DEALING WITH CPAP CLAUSTROPHOBIA & PANIC ATTACKS It's normal to fear being trapped when there's a genuine threat, but people with claustrophobia become fearful in situations where there's no obvious or realistic danger. They'll go out of their way to avoid confined spaces, such as lifts, tunnels, tube trains, etc., or when confined and limited as with a CPAP breathing mask. However, avoiding these places often reinforces the fear. The most common experience is a feeling or fear of losing control. Panic attacks can also have physical symptoms, including shaking, feeling disorientated, nausea, rapid irregular heartbeats, dry mouth, breathlessness, sweating and dizziness. The symptoms of a panic attack are not dangerous, but can be very frightening. Most panic attacks last somewhere from 5 minutes to half an hour. This was enough to prompt SATA to do some research and come up with some ideas on how to deal with this threat to CPAP therapy adherence. THINGS TO REMEMBER IF YOU HAVE CPAP CLAUSTROPHOBIA CPAP claustrophobia is a natural occurrence at the start of CPAP treatment for some people. If you have this you may feel you are struggling to breathe with the mask, hose and pump attached to your face, and have surges of the stress hormone, adrenaline. Getting past this initial hurdle can be a challenge for some, so here is a summary of tips that will help you deal with CPAP claustrophobia CPAP masks will not suffocate you From the start, let’s make it clear that ALL the CPAP masks supplied in the UK are vented, to facilitate carbon dioxide escape.