''The Mind Is Its Own Place'': Amelioration of Claustrophobia in Semantic Dementia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHIZOPHRENIA and OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS of EARLY ONSET Jean Starling & Isabelle Feijo

IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Chapter OTHER DISORDERS H.5 SCHIZOPHRENIA AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS OF EARLY ONSET Jean Starling & Isabelle Feijo Jean Starling FRANZCP, MPH Child and adolescent psychiatrist, Director, Walker Unit, Concord Centre for Mental Health, Sydney, and senior clinical lecturer, Discipline of Psychiatry, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Conflict of interest: none declared Isabelle Feijo FRANZCP Psychiatrist, Walker Unit, Concord Centre for Mental Health, Sydney, Australia and specialist in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy, Swiss Medical Association Conflict of interest: none declared Jackson Acknowledgement: thanks to Pollock; Polly Kwan who vetted the untitled. Cantonese websites This publication is intended for professionals training or practising in mental health and not for the general public. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or IACAPAP. This publication seeks to describe the best treatments and practices based on the scientific evidence available at the time of writing as evaluated by the authors and may change as a result of new research. Readers need to apply this knowledge to patients in accordance with the guidelines and laws of their country of practice. Some medications may not be available in some countries and readers should consult the specific drug information since not all dosages and unwanted effects are mentioned. Organizations, publications and websites are cited or linked to illustrate issues or as a source of further information. This does not mean that authors, the Editor or IACAPAP endorse their content or recommendations, which should be critically assessed by the reader. -

“What About Bob?” an Analysis of Gendered Mental Illness in a Mainstream Film Comedy

“What About Bob?” An Analysis of Gendered Mental Illness in a Mainstream Film Comedy A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the College of Graduate Studies of Northeast Ohio Medical University. Anna Plummer M.D. Medical Ethics and Humanities 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Julie Aultman (Advisor) Dr. Rachel Bracken Brian Harrell Copyright Anna Plummer 2020 ABSTRACT Mental illness has been a subject of fictional film since the early 20th century and continues to be a popular trope in mainstream movies. Portrayals of affected individuals in movies tend to be inaccurate and largely stigmatizing, negatively influencing public perception of mental illness. Recent research suggests that gender stereotypes and mental illness intersect, such that some mental illnesses are perceived as “masculine” and others as “feminine.” This notion may further stigmatize such disorders in individuals, as well as falsely inflate observed gender disparities in certain mental illnesses. Since gendered mental illness is a newly identified concept, little research has been performed exploring the way stereotypical gendered mental illness is depicted in mainstream film. This paper analyzes the movie What About Bob? to show that comedic film perpetuates stigma surrounding feminine mental illness in men and identifies the need for further study of gendered mental illness in movies to ascertain the effect such depictions have on the observed gender disparities in prevalence of certain mental disorders, as well as offers a proposal for coursework for film and medical students. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper would not have been possible without Dr. Aultman, whose teaching inspired me to pursue further education in Medical Ethics and Humanities, and whose guidance has been invaluable not only for this project, but also for addressing ethical issues in the clinic. -

White Matter Abnormalities in Adults with Bipolar Disorder Type-II

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN White matter abnormalities in adults with bipolar disorder type‑II and unipolar depression Anna Manelis1*, Adriane Soehner1, Yaroslav O. Halchenko2, Skye Satz1, Rachel Ragozzino1, Mora Lucero1, Holly A. Swartz1, Mary L. Phillips1 & Amelia Versace1 Discerning distinct neurobiological characteristics of related mood disorders such as bipolar disorder type‑II (BD‑II) and unipolar depression (UD) is challenging due to overlapping symptoms and patterns of disruption in brain regions. More than 60% of individuals with UD experience subthreshold hypomanic symptoms such as elevated mood, irritability, and increased activity. Previous studies linked bipolar disorder to widespread white matter abnormalities. However, no published work has compared white matter microstructure in individuals with BD‑II vs. UD vs. healthy controls (HC), or examined the relationship between spectrum (dimensional) measures of hypomania and white matter microstructure across those individuals. This study aimed to examine fractional anisotropy (FA), radial difusivity (RD), axial difusivity (AD), and mean difusivity (MD) across BD‑II, UD, and HC groups in the white matter tracts identifed by the XTRACT tool in FSL. Individuals with BD‑II (n = 18), UD (n = 23), and HC (n = 24) underwent Difusion Weighted Imaging. The categorical approach revealed decreased FA and increased RD in BD‑II and UD vs. HC across multiple tracts. While BD‑II had signifcantly lower FA and higher RD values than UD in the anterior part of the left arcuate fasciculus, UD had signifcantly lower FA and higher RD values than BD‑II in the area of intersections between the right arcuate, inferior fronto‑occipital and uncinate fasciculi and forceps minor. -

Included Diagnosis List

Press TAB to Diagnosis Diagnosis Description Code F20.0 Paranoid Schizophrenia F20.1 Disorganized Schizophrenia F20.2 Catatonic Schizophrenia F20.3 Undifferentiated Schizophrenia F20.5 Residual Schizophrenia F20.81 Schizophreniform Disorder F20.89 Other Schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia, Unspecified F21 Schizotypal Disorder F22 Delusional Disorder F23 Brief Psychotic Disorder F24 Shared Psychotic Disorder F25.0 Schizoaffective Disorder, Bipolar Type F25.1 Schizoaffective Disorder, Depressive Type F25.8 Other Schizoaffective Disorders F25.9 Schizoaffective Disorder, Unspecified F28 Other Psychotic Disorder Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F29 Unspecified Psychosis Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F30.10 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Unspecified F30.11 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Mild F30.12 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Moderate F30.13 Manic Episode, Severe, Without Psychotic Symptoms F30.2 Manic Episode, Severe, With Psychotic Symptoms F30.3 Manic Episode in Partial Remission F30.4 Manic Episode in Full Remission F30.8 Other Manic Episodes F30.9 Manic Episode, Unspecified F31.0 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Hypomanic F31.10 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic features, Unspecified F31.11 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Mild F31.12 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Moderate F31.13 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Severe F31.2 -

Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD

Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD Thank you for being here sufferers, support, family, professionals. 2 Common Pitfalls in ERP for OCD ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD HELLO! Justin Hughes, MA, LPC Molly Martinez, PhD Owner, Dallas Counseling, PLLC Clinical Psychologist Clinician, Writer, Speaker Specialists in OCD & Anxiety Recovery (SOAR) www.justinkhughes.com www.soartogether.net Dallas, TX Richardson, TX ©Justin K. Hughes, MA, LPC & Molly Martinez, PhD 4 Learning Objectives 1) Overview OCD and ERP 2) Identify roadblocks to effective ERP 3) Identify solutions to address these common pitfalls 5 Want these slides right now??? www.justinkhughes.com/ocd 6 PART ONE: Review The Basics You Probably Know... ● What OCD is ● What ERP is ● That ERP is the PART ONE: gold-standard of Review the evidence-based treatment Basics for OCD 8 For a PRIZE... What is the average amount of symptom reduction after a trial of ERP for OCD? 9 60-70%!! (Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2015; Foa et al., 2010) 10 You Might Know... ● Compulsions function by reducing distress via: ○ Reassurance PART ONE: ○ Avoidance Review the ● ERP is hard Basics ● ERP requires planning ● ERP requires adjustment ● ERP doesn’t always work as expected 11 PART TWO: ERP Pitfalls & Solutions ● Fear-Related Issues ○ Therapists’ Fears ○ Not Addressing the Core Fear ○ Clients’ Fear of Distress ● Covert Compulsive Behaviors ○ Reassurance ○ Mental Compulsions PART TWO: ○ Distraction ● Treatment Plan(ning) Problems ERP Pitfalls & ○ Treatment Compliance Solutions ○ Not Going Far Enough ○ Not Working with Family ○ Wrong Form of Exposure ○ Unrealistic Expectations (Extinction Burst)Medication Myths/Misconceptions ○ Detours & Comorbidities ○ Therapy “Dosing” ○ No Relapse Prevention Plan 13 Fear-Related Pitfalls & Solutions For a PRIZE.. -

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety Disorders Anxiety Disorders Overview n What is anxiety? n Categories of anxiety disorders n Generalized Anxiety Disorder n Panic Disorder n Specific Phobia/Social Phobia n Obsessive Compulsive Disorder n DSM-IV diagnoses n Treatments Anxiety n Probably experienced some of this during the exam n What does it feel like? n When is it a “disorder?” n What is the difference between fear and anxiety? n Anxiety defined as n uneasiness stemming from the anticipation of danger n Fear defined as n a reaction to a specific threat from the real, physical world 1 Anxiety n Anxiety is an evolutionary useful feeling n part of the flight or fight response n useful to have a response of energizing to get out of a situation n sometimes this gets in our way n feels not so adaptive Anxiety n Diagnosing n For a person to be diagnosed as having anxiety, the anxiety must be out of proportion to the perceived threat n The anxiety is recognized by the individual seeking treatment to be excessive or unreasonable Anxiety Disorders n Several types/different diagnoses n Based on formal (topographical) features n Should be distinct n Will see much overlap within a category (e.g. within Anxiety) n Also see overlap between other categories (e.g., OCD and eating disorders) 2 Anxiety Disorders n Six disorders: n Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) n Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) n Phobias n Panic disorder ________________________________ n Acute stress disorder n Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) GAD n One of the most -

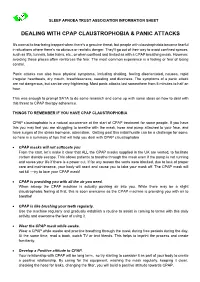

Dealing with Cpap Claustrophobia & Panic Attacks

SLEEP APNOEA TRUST ASSOCIATION INFORMATION SHEET DEALING WITH CPAP CLAUSTROPHOBIA & PANIC ATTACKS It's normal to fear being trapped when there's a genuine threat, but people with claustrophobia become fearful in situations where there's no obvious or realistic danger. They'll go out of their way to avoid confined spaces, such as lifts, tunnels, tube trains, etc., or when confined and limited as with a CPAP breathing mask. However, avoiding these places often reinforces the fear. The most common experience is a feeling or fear of losing control. Panic attacks can also have physical symptoms, including shaking, feeling disorientated, nausea, rapid irregular heartbeats, dry mouth, breathlessness, sweating and dizziness. The symptoms of a panic attack are not dangerous, but can be very frightening. Most panic attacks last somewhere from 5 minutes to half an hour. This was enough to prompt SATA to do some research and come up with some ideas on how to deal with this threat to CPAP therapy adherence. THINGS TO REMEMBER IF YOU HAVE CPAP CLAUSTROPHOBIA CPAP claustrophobia is a natural occurrence at the start of CPAP treatment for some people. If you have this you may feel you are struggling to breathe with the mask, hose and pump attached to your face, and have surges of the stress hormone, adrenaline. Getting past this initial hurdle can be a challenge for some, so here is a summary of tips that will help you deal with CPAP claustrophobia CPAP masks will not suffocate you From the start, let’s make it clear that ALL the CPAP masks supplied in the UK are vented, to facilitate carbon dioxide escape. -

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

/ translated fom Russian into English using https://translate.google.com / Version from 03 October 2018 APPROVED BY Acting Director of NIIFM academician of RAS ___________________ L.I. Aftanas /signature, stamp/ Clinical trial subscription Title: "Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of Resveratrol in the treatment of depression: a double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in two parallel groups of patients" ("Resveratrol") Principal investigators: academician of RAS Aftanas L.I., Danilenko K.V., MD responsible investigator: Markov A.A. RATIONALE In July 2015, the predominant involvement of the SIRT1 gene in the prevalence of depression in the Chinese population was revealed (CONVERGE, Nature, 2015). This gene mediates the activity of the sirtuin-1 protein, which is an antioxidant / cytoprotective enzyme (Kim et al., 2012). For the SIRT1 enzyme, a known activator is natural phytoalexin, a flavonoid-polyphenol resveratrol. Two-thirds of US residents who take dietary supplements (dietary supplements) in their food consume resveratrol-containing dietary supplements (Hubbard, Sinclair, 2014). The clinical effect of resveratrol is being studied in diabetes and obesity, cancer and cardiovascular diseases (www.clinicaltrials.gov). However, no studies have been conducted on the effects of resveratrol on depression (based on an analysis of the PubMed and www.clinicaltrials.gov databases). During the research, the dependence of the therapeutic effect on the structural features of the SIRT1 gene and its functional activity will be studied using the example of the sirtuin-1 enzyme. The structural features of the gene were studied in 2016-2017. within the framework of the Russian Science Foundation project No. 16-15-00128 "Structural features of the SIRT1 gene as a basis for the choice of personalized drug therapy for depression", which includes the Resveratrol study. -

Specialty Mental Health Outpatient Services Icd-10 Covered Diagnoses Table Effective October 1, 2019 Through September 30, 2020

SPECIALTY MENTAL HEALTH OUTPATIENT SERVICES Enclosure 2 ICD-10 COVERED DIAGNOSES TABLE EFFECTIVE OCTOBER 1, 2019 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Press TAB to Diagnosis Diagnosis Description Code F20.0 Paranoid Schizophrenia F20.1 Disorganized Schizophrenia F20.2 Catatonic Schizophrenia F20.3 Undifferentiated Schizophrenia F20.5 Residual Schizophrenia F20.81 Schizophreniform Disorder F20.89 Other Schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia, Unspecified F21 Schizotypal Disorder F22 Delusional Disorder F23 Brief Psychotic Disorder F24 Shared Psychotic Disorder F25.0 Schizoaffective Disorder, Bipolar Type F25.1 Schizoaffective Disorder, Depressive Type F25.8 Other Schizoaffective Disorders F25.9 Schizoaffective Disorder, Unspecified F28 Other Psychotic Disorder Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F29 Unspecified Psychosis Not Due to a Substance or Known Physiological Condition F30.10 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Unspecified F30.11 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Mild F30.12 Manic Episode Without Psychotic Symptoms, Moderate F30.13 Manic Episode, Severe, Without Psychotic Symptoms F30.2 Manic Episode, Severe, With Psychotic Symptoms F30.3 Manic Episode in Partial Remission F30.4 Manic Episode in Full Remission F30.8 Other Manic Episodes F30.9 Manic Episode, Unspecified F31.0 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Hypomanic F31.10 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic features, Unspecified F31.11 Bipolar Disorder, Current Episode Manic, Without Psychotic Features, Mild F31.12 Bipolar Disorder, Current -

Risk of Depression and Anxiety in Adults with Cerebral Palsy

Supplementary Online Content Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. Published online December 28, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4147 eTable 1. Read codes and associated Read terms used to define Cerebral Palsy eTable 2. Risk of depression and anxiety in people with CP with and without co-morbid ID (excluding all people without CP who had a diagnosis of ID, n=24) eFigure. Kaplan Meier survival plots This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2018 Smith KJ et al. JAMA Neurology. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/25/2021 eTable 1. Read codes and associated Read terms used to define Cerebral Palsy Read code Read term F23y400 Ataxic diplegic cerebral palsy F23y000 Ataxic diplegic cerebral palsy F137.11 Athetoid cerebral palsy F137000 Athetoid cerebral palsy F2B..00 Cerebral palsy F2Bz.00 Cerebral palsy NOS F230100 Cerebral palsy with spastic diplegia F23..00 Congenital cerebral palsy F23y300 Dyskinetic cerebral palsy F23..12 Infantile cerebral palsy F23y200 Spastic cerebral palsy F230111 Spastic diplegic cerebral palsy F2B1.00 Spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy F2B0.00 Spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy F23yz00 Other infantile cerebral palsy NOS Fyu9000 [X]Other infantile cerebral palsy F23y.00 Other congenital cerebral palsy F23y100 Flaccid infantile cerebral palsy F2By.00 Other cerebral palsy Fyu9.00 [X]Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes F23z.00 Congenital cerebral palsy NOS F23..11 Congenital spastic cerebral palsy F23y600 Choreoathetoid cerebral palsy © 2018 Smith KJ et al. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization -1- Preface In the early 1960s, the Mental Health Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) became actively engaged in a programme aiming to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. At that time, WHO convened a series of meetings to review knowledge, actively involving representatives of different disciplines, various schools of thought in psychiatry, and all parts of the world in the programme. It stimulated and conducted research on criteria for classification and for reliability of diagnosis, and produced and promulgated procedures for joint rating of videotaped interviews and other useful research methods. Numerous proposals to improve the classification of mental disorders resulted from the extensive consultation process, and these were used in drafting the Eighth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8). A glossary defining each category of mental disorder in ICD-8 was also developed. The programme activities also resulted in the establishment of a network of individuals and centres who continued to work on issues related to the improvement of psychiatric classification (1, 2). The 1970s saw further growth of interest in improving psychiatric classification worldwide. Expansion of international contacts, the undertaking of several international collaborative studies, and the availability of new treatments all contributed to this trend. Several national psychiatric bodies encouraged the development of specific criteria for classification in order to improve diagnostic reliability. In particular, the American Psychiatric Association developed and promulgated its Third Revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which incorporated operational criteria into its classification system. -

One 3 Hour Exposure Session Was As Effective As 5 One Hour Sessions of Either Exposure Or Cognitive Therapy for Claustrophobia

Evid Based Mental Health: first published as 10.1136/ebmh.4.3.86 on 1 August 2001. Downloaded from One 3 hour exposure session was as effective as 5 one hour sessions of either exposure or cognitive therapy for claustrophobia Öst LG, Alm T,Brandberg M, et al. One vs five sessions of exposure and five sessions of cognitive therapy in the treatment of claustrophobia. Behav Res Ther 2001 Feb;39:167–83. QUESTIONS: Is 1 session of exposure treatment (ET) effective in people with claustrophobia? Is 1 session of ET as effective as 5 sessions of ET or 5 sessions of cognitive therapy (CT)? Design did not differ among the 3 treatment groups after treat- Randomised (unclear allocation concealment*), un- ment or at 1 year. blinded*, controlled trial with 1 year of follow up. Conclusion Setting In people with claustrophobia, 1 session of exposure Uppsala and Stockholm counties, Sweden. treatment (ET) was as effective as 5 sessions of ET or 5 sessions of cognitive therapy. Patients *See glossary. 50 patients who were 18–60 years of age, were afraid of and avoided confined spaces, had claustrophobia for >1 year (mean duration 26 y), could not complete > 50% of the steps in behavioural tests, and had no psychotic or COMMENTARY organic illnesses or other psychiatric problems requir- Claustrophobia, a fear of enclosed spaces, has a lifetime ing immediate treatment. Follow up was 92% (mean age prevalence of about 4% and can be substantially handicap- 41 y, 91% women). ping in a proportion of cases.1 Of course, most people with fears of sufficient persistence and intensity to meet diagnos- Intervention tic criteria for specific phobia manage to find ways of living Patients were allocated to 1 of 4 groups: one 3 hour ses- with their fear and few seek professional help.