A Soldier's Voyage of Self Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15917 Hon. Tammy Baldwin Hon. Edolphus Towns

July 13, 2005 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 15917 HONORING GAYLORD NELSON ican branch of a Sikh political party that is from India on October 7, 1987. The event was strongly in support of independence for shown throughout India on an Indian tele- Khalistan, the Sikh homeland. Leaders of Dal vision channel called Aaj Tak on July 6. Dr. HON. TAMMY BALDWIN Aulakh was interviewed by a California rep- OF WISCONSIN Khalsa have been arrested in India, along with resentative of Voice of America. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES other leaders, for raising the Khalistani flag As soon as Dr. Aulakh raised the flag, slo- there. gans of ‘‘Khalistan Zindabad’’ (‘‘Long live Wednesday, July 13, 2005 In all, dozens were charged last month on Khalistan’’) were raised. Speakers at the Ms. BALDWIN. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to the 21st anniversary of India’s military attack event spoke out strongly for a free and inde- pay tribute to the life and legacy of Gaylord on the Golden Temple for daring to raise the pendent Khalistan. Speakers included Dr. Nelson of Wisconsin. Since his death a little flag of Khalistan and making speeches, even Awatar Singh Sekhon from Canada, Dr. more than a week ago, at age 89, much has though these are not crimes in India. They are Aulakh, Sardar Sekhon, Sardar Ajit Singh not crimes in any democratic country. Yet Pannu, Dr. Ranbir Singh Sandhu from Tracy, been written about this extraordinary states- California, Sardar Karj Singh Sandhu from man, environmentalist, husband, father, and these charges follow the arrests of 35 Sikhs in Philadelphia, Dr. -

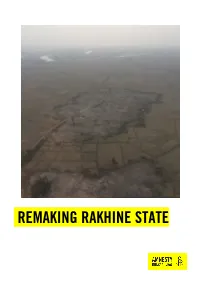

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

July 2020 (23:45 Yangon Time)

Allocation Strategy Paper 2020: FIRST STANDARD ALLOCATION DEADLINE: Monday, 20 July 2020 (23:45 Yangon time) I. ALLOCATION OVERVIEW I.1. Introduction This document lays the strategy to allocating funds from the Myanmar Humanitarian Fund (MHF) First Standard Allocation to scale up the response to the protracted humanitarian crises in Myanmar, in line with the 2020 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). The allocation responds also to the critical underfunded situation of humanitarian requirements by mid-June 2020. As of 20 June, only 23 per cent of the 2020 HRP requirements, including the revised COVID-19 Addendum, have been met up to now (29 per cent in the case of the mentioned addendum), which is very low in comparison with donor contributions against the HRP in previous years for the same period (50 per cent in 2019 and 40 per cent in 2018). This standard allocation will make available about US$7 million to support coordinated humanitarian assistance and protection, covering displaced people and other vulnerable crisis-affected people in Chin, Rakhine, Kachin and Shan states. The allocation will not include stand-alone interventions related to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has been already supported through a Reserve Allocation launched in April 2020, resulting in ten funded projects amounting a total of $3.8 million that are already being implemented. Nevertheless, COVID-19 related actions may be mainstreamed throughout the response to the humanitarian needs. In addition, activities in Kayin State will not be included in this allocation, due to the ongoing projects and level of funding as per HRP requirements. -

The Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute: Sub-National Units As Ice-Breakers

The Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute: Sub-National Units as Ice-Breakers Jabin T. Jacob* Introduction The Sino-Indian boundary dispute is one of the oldest remaining disputes of its kind in the world and given the “rising” of the two powers in the international system, also potentially one of the most problematic. While the dispute has its origins in the British colonial era under geopolitical considerations of “the Great Game,” where Tibet was employed as a buffer between British India and the Russians with little or no thought to Chinese views on the matter. The dispute has two major sections – in India’s northeast and in India’s northwest. The Simla Convention of 1914 involved the British, Chinese and the Tibetans but the eventual agreement between Britain and Tibet in which the alignment of the Tibet-Assam boundary was agreed upon in the form of the McMahon Line was not recognized by China. And today, this disagreement continues in the Chinese claim over some 90,000 km2 of territory in Indian control covering the province of Arunachal Pradesh. Arunachal, which the Chinese call “Southern Tibet,” includes the monastery town of Tawang, birthplace of the Sixth Dalai Lama, and a major source of contention today between the two sides. Meanwhile, in the Indian northwest – originally the most significant part of the dispute – the Chinese managed to assert control over some 38,000 km2 of territory in the 1962 conflict. This area called Aksai Chin by the Indians and considered part of the Indian province of Jammu and Kashmir, was the original casus belli between the newly independent India and the newly communist China, when the Indians discovered in the late 1950s that the Chinese had constructed a road through it connecting Kashgar with Lhasa. -

Nishaan – Blue Star-II-2018

II/2018 NAGAARA Recalling Operation ‘Bluestar’ of 1984 Who, What, How and Why The Dramatis Personae “A scar too deep” “De-classify” ! The Fifth Annual Conference on the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, jointly hosted by the Chardi Kalaa Foundation and the San Jose Gurdwara, took place on 19 August 2017 at San Jose in California, USA. One of the largest and arguably most beautiful gurdwaras in North America, the Gurdwara Sahib at San Jose was founded in San Jose, California, USA in 1985 by members of the then-rapidly growing Sikh community in the Santa Clara Valley Back Cover ContentsIssue II/2018 C Travails of Operation Bluestar for the 46 Editorial Sikh Soldier 2 HERE WE GO AGAIN: 34 Years after Operation Bluestar Lt Gen RS Sujlana Dr IJ Singh 49 Bluestar over Patiala 4 Khushwant Singh on Operation Bluestar Mallika Kaur “A Scar too deep” 22 Book Review 1984: Who, What, How and Why Jagmohan Singh 52 Recalling the attack on Muktsar Gurdwara Col (Dr) Dalvinder Singh Grewal 26 First Person Account KD Vasudeva recalls Operation Bluestar 55 “De-classify !” Knowing the extent of UK’s involvement in planning ‘Bluestar’ 58 Reformation of Sikh institutions? PPS Gill 9 Bluestar: the third ghallughara Pritam Singh 61 Closure ! The pain and politics of Bluestar 12 “Punjab was scorched 34 summers Jagtar Singh ago and… the burn still hurts” 34 Hamid Hussain, writes on Operation Bluestar 63 Resolution by The Sikh Forum Kanwar Sandhu and The Dramatis Personae Editorial Director Editorial Office II/2018 Dr IJ Singh D-43, Sujan Singh Park New Delhi 110 -

Central-Rakhine-State-Q4-Report.Pdf

Protection Incident Monitoring System | Protection Sector Myanmar PROTECTION INCIDENT MONITORING SYSTEM: DASHBOARD Reporting Period: October – December 2016 Reporting Area: Central Rakhine State KEY INFORMATION KEY FIGURES In the central parts of Rakhine state, movement restrictions increased for IDPs and Muslims in most locations during the first weeks following the 9 59 reported incidents October attacks against Border Guard Police (BGP) posts in the northern part of Rakhine State. Many humanitarian agencies temporarily reduced 1343 victims their outreach to IDP camps as a precautionary measure due to fear expressed by staff. 77 child victims A total of 59 incidents were reported, affecting 1,343 persons, BREAKDOWN OF VICTIMS BY GENDER: predominantly men. 53% of the incidents were reported as being perpetrated by the government principally the BGP, the Myanmar Police and the Tatmadaw. Female 37 250 people, including 62 children are reported to have been tortured Male 1306 during a military operation in Rathedaung Township. CONTENTS DATA GUIDANCE 1. Protection Incident Monitoring Info-graphic This PIMS dashboard is a quarterly publication of This infographic shows the number of reported incidents and the total number the Protection Sector in Myanmar. This publication aims to provide an overview and trend of affected victims broken down by male, female and children per geographic analysis of the protection concerns prevalent in area. specific regions of Myanmar. This, we hope, will 2. Protection Incident Trend Analysis assist to inform protection and programme This analysis shows trends of protection incidents that occurred in one year. interventions to address protection gaps. This includes (i) Incident trend by violation type and township; (ii) Incident trend by perpetrator and township; (iii) Child victims by violation type; However, PIMS reports do not contain all (iv) Incident trend by township. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: Multiple Dates | Published 18 October 2018 | Version 1.0 CE20130326MMR 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E Thimphu NUMBER OF AFFECTED SETTLEMENTS GROUPED BY LEVEL OF DESTRUCTION ¥¦¬ Level of destruction Buthidaung Maungdaw Rathedaung Total C H I N A Less than 50% destroyed 71 59 4 134 I N D I A More than 50% destroyed 18 62 80 N N Dhaka " Completely destroyed (>90%) 7 156 15 178 " 0 ' 0 ' ¥¦¬ 5 5 2 2 ° ° 1 1 2 Hano¥¦¬i In Tu Lar 2 M YA N M A R ¥¦¬Naypyidaw Vientiane Map location ¥¦¬ T H A I L A N D N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 8 Shee Dar 8 Bangkok 1 1 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 2 Phnom Penh ¥¦¬ Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Nan Yar Kaing (NaTaLa) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar N N " " 0 ' 0 Hpon Thi Laung Boke ' 1 1 Affected settlements in 1 1 ° ° 1 1 2 Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Mu Hti Pa Da Kar Taung 2 Rathedaung Townships of Pa Da Kar Ywar Thit Min Gyi (Ku Lar) Wet Kyein Rakhine State in Myanmar Pe Lun Kha Mway Saung Paing Nyar This map illustrates areas of satellite-detected destroyed or otherwise damaged settlements Goke Pi N N " " 0 ' 0 ' in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung 4 See inset for close-up view 4 ° ° 1 1 2 Townships in Northern Rakhine State in of destroyed structures 2 Myanmar. -

(C) Within Whose Jurisdiction the Plaintiff

25th Bihar Civil Judge (Pre.) Exam , 2000 (G.K. & Law) 109 (C) within whose jurisdiction the plaintiff (B) a party can amend its pleadings at any resides stage (D) within whose local limits ofjurisdiction (C) cannot allow amendment of pleadings the property is situated (D) can allow amendment ofitten statement 89. The principle of Res Judicata only (A) applies to criminalproceedings also (B) applies to suil only 96. The Court (C) applies to execution proceedings also (A) has no power to record admissions of (D) can be decided by the parties to the suit parties at any stage of the proceeding 90. Compensatory costs in respect of false or (B) has power to record admissions only vexatious claim or defence can be awarded on issues of law upto (C) has power to record admissions of (A) Rs.10,000/- (B) Rs. 1,000/- parties at any stage of the proceeding (C) Rs. 500/- (D) Rs. 3,000/- (D) cannot record admissions at all 91. Books of account 97. No one shall be ordered to attend the Court (A) are liable to attachment and sale in in person to give evidence execution of a decree (A) unless he resides within 50 kilometres (B) are not liable to attachment and sale in execution of a decree from the Court (C) are no evidence in the eye of law (B) unless he resides within 100 kilometres (D) can be the sole evidence to decide a suit from the Court house 92. An appeal shall lie (C) unless he resides within 1000 kilometres (A) from all orders passed by the Court from the Court (B) only from such orders as provided In (D) unless he resides within 500 kilometres the Code of Civil Procedure from the Court house (C) from none of the orders passed by the 98. -

Of the Rome Statute

ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 1/146 RH PT Cour Penale (/\Tl\) _ni _t_e__r an _t_oi _n_a_l_e �i��------------------ ----- International �� �d? Crimi nal Court Original: English No.: ICC-01/19 Date: 4 July 2019 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Geoffrey Henderson SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH / REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR PUBLIC With Confidential EX PARTE Annexes 1, 5, 7 and 8, and Public Annexes 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 2/146 RH PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr Philipp Ambach No. ICC-01/19 2/146 4 July 2019 ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 3/146 RH PT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 II. LEVEL OF CONFIDENTIALITY AND REQUESTED PROCEDURE .................... 8 III. PROCEDURAL -

Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War: a Systems Level Approach

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies Josef Korbel School of International Studies Summer 2009 Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War: A Systems Level Approach Aldo D. Abitol University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/advancedintlstudies Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Aldo D. Abitbol, “Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War: A systems Level Approach,” Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies 1 (Summer 2009): 74-88. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War: A Systems Level Approach This article is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/advancedintlstudies/23 Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War A SYSTEMS LEVEL APPRAOCH ALDO D. ABITBOL University of Denver M.A. Candidate, International Security ______________________________________________________________________________ The emergence of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations as regional powers and future challengers to U.S. hegemony has been predicted by many, and is a topic of much debate among the IR community today. Interestingly, three of these nations have warred against each other in the past and, coincidentally or not, it was the nations that shared borders: India and China and China and Russia. -

St. Teresa's School

ST. TERESA’S SCHOOL st 1 Raj. Girls Battalion NCC NAME: AVANI SHEKHAWAT FATHER’s NAME: MR. BHAWANI SINGH SHEKHAWAT RANK: CADET CLASS: IX PROFESSTION: STUDENT TOPIC: WARTIME GALLENTRY AWARD ‘PARAM VEER CHAKRA’ WINNERS PARAM VEER CHAKRA India's highest military adornment, after Bharat Ratna which is awarded to those courageous and daring or the braves ,who self-sacrifice their life for their motherland, while fighting with enemy, whether on land, at sea or in the air. Param Veer Chakra cannot be asked, it need to be earnrd. This award comes to those ,if death strikes before them, they prove their blood, they swear, they can kill death. It was introduced on 26 January, 1950 on the first Republic Day. This award may be given posthumously. The medal of the PVC was designed by Savitri Khanolkar. The list of 21 Brave Military Men who have received this award to date are: 1. Maj. Somnath Sharma 4 Kumaon|Badgam, Kashmir|November 3, 1947 Major Sharma, with a broken arm, staved off enemy attacking on Badgam aerodrome and Srinagar. He was personally filling magazines and issuing them to the light machine gunners. His death inspired the fellow soldiers to fight the enemy 7:1 for six hours. 2. Naik Jadunath Singh 1 Rajput|Taindhara, Naushera, Kashmir| February 6, 1948 Naik Singh was commanding a forward post when the enemy attacked. We suffered heavy losses. Eventually Singh somehow saved his troops, but fell to bullets. 3. 2nd Lt Rama Raghoba Rane Bombay Engineers|Naushera-Rajouri Road|April 8-11, 1948 Rane braved machine gun fire, cleared mines and roadblocks as he laid a path for tanks.