Addressing Food Insecurity- the Case of DR Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Download File

UNICEF DRC | COVID-19 Situation Report COVID-19 Situation Report #9 29 May-10 June 2020 /Desjardins COVID-19 overview Highlights (as of 10 June 2020) 25702 • 4.4 million children have access to distance learning UNI3 confirmed thanks to partnerships with 268 radio stations and 20 TV 4,480 cases channels © UNICEF/ UNICEF’s response deaths • More than 19 million people reached with key messages 96 on how to prevent COVID-19 people 565 recovered • 29,870 calls managed by the COVID-19 Hotline • 4,338 people (including 811 children) affected by COVID-19 cases under 388 investigation and 837 frontline workers provided with psychosocial support • More than 200,000 community masks distributed 2.3% Fatality Rate 392 new samples tested UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response Kinshasa recorded 88.8% (3,980) of all confirmed cases. Other affected provinces including # of cases are: # of people reached on COVID-19 through North Kivu (35) South Kivu (89) messaging on prevention and access to 48% Ituri (2) Kongo Central (221) Haut RCCE* services Katanga (38) Kwilu (2) Kwango (1) # of people reached with critical WASH Haut Lomami (1) Tshopo (1) supplies (including hygiene items) and services 78% IPC** Equateur (1) # of children who are victims of violence, including GBV, abuse, neglect or living outside 88% DRC COVID-19 Response PSS*** of a family setting that are identified and… Funding Status # of children and women receiving essential healthcare services in UNICEF supported 34% Health facilities Funds # of caregivers of children (0-23 months) available* DRC COVID-19 reached with messages on breadstfeeding in 15% 30% Funding the context of COVID-19 requirements* : Nutrition $ 58,036,209 # of children supported with distance/home- 29% based learning Funding Education Gap 70% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Funds available include 9 million USD * Risk Communication and Community Engagement UNICEF regular ressources allocated by ** Infection Prevention and Control the office for first response needs. -

A Turning Point for Manual Drilling in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Rural Water Supply Network Publication 2020-2 C H Kane & Dr K Danert 2020 A Turning Point for Manual Drilling in the Democratic Republic of Congo Publication 2020-2 Dedication Summary The authors dedicate this publication to Gambo Nayou This publication provides a source of inspiration from a country that (1963 to 2016). tends to otherwise be associated with humanitarian crisis, persistent con- flicts, recurrent civil wars and a generally obsolete road infrastructure. It describes over a decade of pioneering efforts by UNICEF, the Gov- ernment of the Democratic Republic of Congo and partners to intro- duce and professionalise manual drilling. This professionalisation pro- gramme is very important as it is estimated that only 43% of the pop- ulation have access to a basic drinking water service (JMP, 2019). In addition, the majority of the DRC is favourable to manual drilling (42% classified with very high or high potential, and 24% as moderate). The most favourable area for manual drilling is in the western part of Gambo was a man of vision, a person who looked into the future and the country, which has a soft geological layer of considerable extent saw things that many could not even imagine. He passionately and thickness. shared what he knew with others. Over a ten-year period, manual drilling, using the rota-jetting tech- Following his experiences of manual drilling in Niger and Chad, nique, has gone from a little-known technology in the DRC to an ef- Gambo reached out to the Association of Manual Drillers from Chad fective technology that has enabled about 650,000 people to be pro- (Tchadienne pour la Promotion des Entreprises Spécialisées en For- vided with a water service. -

World Bank Document

.. HOLD FOR RELEASE • INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 1818 H STREET. ·N.W, WASHINGTON 25, D. C TE' EPHONE. EXECUTIVE 3-6360 Public Disclosure Authorized I:JA Press Release No. 69/19 Subject: IDA and UNDP financing for May 7, 1969 highway technical assistance in Congo (Kinshasa.) A credit of $6 million from the International Development Association (IDA) and a $1.5 million technical assistance grant from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) will enable th~ Government to take the first steps toward rehabilitating its highway network. Public Disclosure Authorized The Government is contributing the equivalent of $2 million toward the cost of the project. The Congo's major centers of population, production and trade are widely s~nttered and an efficient and extensive transport system is essential if the • c,.·,untry is to be integrated administratively, politically and economically. Tile once efficient rail, river and road transport system has deteriorated since 1.udependence and the difficulties which followed. The condition of the highways Public Disclosure Authorized is particularly acute because of a serious weakening of administration, and lack of maintenance and of equipment replacements. The measures now to be undertaken are of an emergency nature and only a small part of what has to be done to establish a viable highway system and administration. However, they will assure more efficient use of personnel and ·funds being used for highway maintenance and rehabilitation; halt the r~1r:i.d deterioration of some of the most important roads; achieve substantial Public Disclosure Authorized s;.:v-tngs in vehicle operating costs; and will encourage incn:?ased production ~-7 ?emoving potential bottlenecks to economic recovery • • /more \ IDA P.R. -

Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Thomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 The effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Configurations of Authority in Kongo Central Province: Governance, Access to Justice, and Security in the Territory of Muanda

JSRP Paper 35 Configurations of Authority in Kongo Central province: governance, access to justice, and security in the territory of Muanda Tatiana Carayannis, José Bazonzi, Aaron Pangburn (Social Science Research Council) February 2017 © Tatiana Carayannis, José Bazonzi, Aaron Pangburn (2017) Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this paper, the Justice and Security Research Programme and the LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher, nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this paper should be sent to: The Editor, Justice and Security Research Programme, International Development Department, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE Or by email to: [email protected] Contents Introduction ............................................................................ 4 A History of Public Authority in Kongo Central ....................... 5 Justice, security, and public protection ................................ 12 Competition for Public Authority .......................................... 17 External Interventions .......................................................... 24 Conclusion ............................................................................ 26 Configurations of authority in Kongo Central province: Governance, access to justice and security in the territory of Muanda Tatiana Carayannis, Jose Bazonzi, and Aaron Pangburn Introduction One of the objectives of the Justice and Security Research Program (JSRP) is to analyze both formal and informal governance and authority structures in conflict affected areas in Central Africa and to examine security and justice practices provided by these structures. -

Situation Report

BABAY ZIKA VIRUS SITUATION REPORT YELLOW FEVER 5 AUGUST 2016 SUMMARY . In Angola, as of 28 July 2016 a total of 3818 suspected cases have been reported, of which 879 are laboratory confirmed. The total number of reported deaths is 369, of which 119 were reported among confirmed cases. Suspected cases have been reported in all 18 provinces and confirmed cases have been reported in 16 of 18 provinces and 80 of 126 reporting districts. Mass reactive vaccination campaigns that first began in Luanda have expanded to cover most of the other affected parts of Angola and recently have focused on border areas with the Democratic Republic of The Congo (DRC). The next vaccination phase targeting three million people in 18 districts is expected to start on 16 August. The recent technical difficulties at the national laboratory in DRC have been resolved and laboratory analysis of backlog samples is ongoing. As of 27 July, eight patients have tested positive among 700 samples tested and investigations are ongoing to collect additional information. Since the beginning of the outbreak, DRC has reported (as of 27 July) a total of 2051 suspected cases including 76 confirmed cases and 95 reported deaths (Table 1). Cases have been reported in 22 Health Zones in five of 26 provinces. Of the 76 confirmed cases, 67 are reported as imported from Angola, two are sylvatic1 (not related to the outbreak) and seven are autochthonous2. The number of suspect cases is increasing in Kinshasa, Kongo Central, Kwango, Tshuapa and Lualaba provinces in the week ending 16 July. In DRC, reactive vaccination campaigns started on 20 July and finished on 29 July in Kisenso Health Zone in Kinshasa province and in Kahemba, Kajiji and Kisandji Health Zones in Kwango province. -

Drc Survey: an Overview of Demographics, Health, and Financial Services in the Democratic Republic of Congo

DRC SURVEY: AN OVERVIEW OF DEMOGRAPHICS, HEALTH, AND FINANCIAL SERVICES IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON STRATEGIC ANALYSIS, RESEARCH & TRAINING (START) CENTER OVERVIEW REPORT TO THE BILL & MELINDA GATES FOUNDATION MARCH 29, 2017 PRODUCED BY: NAUGHTON B, ABRAMSON R, WANG A, KWAN-GETT T EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The DemOcratic Republic Of COngO is One Of Africa’s largest cOuntries, but ranks near the bottom in most glObal indicatOrs. Weakened by decades Of viOlence, instability, and unchecked epidemics, the DRC faces challenges On many frOnts, with a nearly collapsed and Overburdened health system, crippled infrastructure, humanitarian crises, and persisting cOnflict in the Eastern regions. Despite these formidable challenges, and with the suppOrt Of private, bilateral, multilateral, and nOn-profit organizations, the DRC has seen imprOvements in sOme areas Over the past few decades. However, further investments targeted at the key catalysts Of develOpment are required as the cOuntry seeks health, financial, and physical security amidst a rapidly changing and uncertain landscape. To help infOrm strategic investments in the DRC, the Integrated Delivery team asked the Strategic Analysis and Research Training (START) Center at the University of Washington (UW) to develop an overview of demographics, health, and financial well-being in the DRC. The START team fOund concerns abOut the quality of much of the published data on the DRC. The data that was available showed stark health and social disparities by gender, class, geography, and urban vs. rural setting. Key challenges that were identified in the DRC include the fOllOwing: Demographics & Infrastructure § Weak infrastructure is a majOr hindrance tO ecOnOmic develOpment. -

Public Annex A

ICC-01/04-02/06-2008-AnxA 11-08-2017 1/76 NM T Public Annex A 11/08/2017 OHCHR | Statement of the High Commissioner to the Interactive dialogue on the DeICC-01/04-02/06-2008-AnxAmocratic Republic of the Congo, 3 5 11-08-2017th session of t h2/76e H… NM T 中文 | اﻟﻌرﺑﯾﺔ | Go to navigation | Go to content English | Français | Español | русский WHAT ARE HUMAN RIGHTS? DONATE HUMAN RIGHTS WHERE WE HUMAN RIGHTS NEWS AND PUBLICATIONS AND HOME ABOUT US ISSUES BY COUNTRY WORK BODIES EVENTS RESOURCES English > News and Events > DisplayNews 14 15 0 Statement of the High Commissioner to the Interactive dialogue on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 35th session of the Human Rights Council 20 June 2017 Excellencies, Just three months ago, my Office reported to this Council serious concerns about the human rights violations and abuses committed by the Congolese army and police, and the Kamuina Nsapu militia, in Kasai, Kasai Central and Kasai Oriental. Subsequently, when the two UN experts were killed, the Minister for Human Rights of the Democratic Republic of the Congo called for a joint investigation to bring the perpetrators of human rights violations and abuses to justice. Since then the humanitarian and human rights situation has deteriorated dramatically and various actors are fuelling ethnic hatred, resulting in extremely grave, widespread and apparently planned attacks against the civilian population in the Kasais. Last week, given the gravity of the allegations received and restricted access to parts of the greater Kasai area, and in line with my statement to this Council on 6 June, I deployed a team of OHCHR investigators to interview recent refugees from the Kasais. -

Drc Hno-Hrp 2021 at a Glance.Pdf

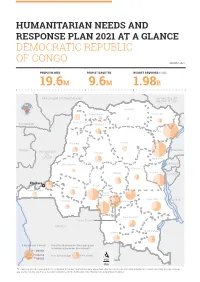

HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE PLAN 2021 AT A GLANCE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO JANUARY 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED BUDGET REQUIRED (USD) 19.6M 9.6M 1.98B RÉPUBLIQUE CENTRAFRICAINE RÉPUBLIQUE DU SOUDAN DU SUD Bas-Uele Nord-Ubangi Haut-Uele Sud-Ubangi CAMEROUN Mongala Ituri Equateur Tshopo GABON OUGANDA RÉPUBLIQUE Tshuapa DU CONGO Nord-Kivu Maï-Ndombe RWANDA Maniema Sud-Kivu Sankuru BURUNDI insasa Kasaï Kwilu Kongo-Central Kasaï- Central Tanganyika TANZANIE Kwango Lomami Haut-Lomami Kasaï- Oriental ANGOLA Haut-Katanga Lualaba # de pers.dans le besoin Proportion de personnes ciblées par rapport au nombre de personnes dans le besoin 1 000 000 500 000 Pers. dans le besoin Pers. ciblées O 100 000 100 Km The names used in the report and the presentation of the various media do not imply any opinion whatsover on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of their authorities, nor the delimitation of its boundaries or geographical boundaries. ZAMBIE HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE PLAN 2020 AT A GLANCE Severity of needs INTERSECTORAL SEVERITY OF NEEDS (2021) MINOR MODERATE STRICT CRITICAL CATASTROPHIC 11% 17% 44% 24% 4% CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN CAMEROON Nord-Ubangi Sud-Ubangi Haut-Uele Bas-Uele Mongala Ituri Equateur Tshopo REPUBLIC OF Tshuapa OUGANDA CONGO GABON Nord-Kivu RWANDA Maï-Ndombe Maniema Sud-Kivu BURUNDI Kinshasa Sankuru !^ Kwilu Kasaï Kongo-Central Lomami Kasaï- TANZANIA Central Tanganyika Kwango Kasaï- Oriental Haut-Lomami Haut-Katanga Lualaba ANGOLA Severity of needs O Catastrophic Critical 100 Strict Km ZAMBIA Moderate Minor None The designations employed in the report and the presentation of the various materials do not imply any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of countries, territories, cities or areas, or of their authorities, nor of the delimitation of its frontiers or geographical limits. -

Fertility, Ethnicity, Education, and the Demographic Dividend in the Democratic Republic of the Congo*

Fertility, Ethnicity, Education, and the Demographic Dividend in the Democratic Republic of the Congo* David Shapiro Department of Economics Pennsylvania State University [email protected] and Basile O. Tambashe Department of Population Sciences and Development University of Kinshasa [email protected] October 2015 Abstract In the mid-1950s, a massive survey in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) provided high-quality demographic data that revealed very sharp fertility differentials among the country’s different ethnic groups. At that time, the vast majority of women of reproductive age had never been to school, so women’s education was not a factor pertinent to fertility. Over the succeeding decades, especially following independence in 1960, women increasingly went to school and advanced in school, especially in Kinshasa, the capital. In the city, women’s increased educational attainment was associated with lower fertility, particularly for women who at least reached the secondary schooling level. At the same time, fertility differences by ethnic group have diminished over time in the city. This paper examines fertility differences by education and by ethnicity in the country as a whole, distinguishing Kinshasa from other urban places and with separate analyses for those in rural areas as well. We seek to determine if the increased importance for fertility of education and reduced importance for fertility of ethnicity witnessed in Kinshasa is also apparent for the country as a whole. In addition, we explore the prospects for a demographic dividend in the DRC, reflecting both existing and emerging levels of fertility, both at the national and provincial levels.