NI Peace Monitoring Report 2013 Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Call to All to Work for It Wiat MUST BE DONE TODAY

PEARSE CAN CASEMENT WILL No. 308 APRIL 1970 A call to all to work for it BRITISH TROOPS REMOVE G.A.A. WiAT MUST BE DONE TODAY TRICOLOUR IN DERRY A firm grasp of reality is a great revolutionary weapon. The Reunited after protest revolutionary or reformer who bases his actions on things which iiR. EDWARD McATEER is to protest against the action of are not condemns himself to defeat and frustration. m British troops who entered the private grounds of the G.A.A., Therefore as Easter comes round once more, and we celebrate at Celtic Park, Derry, and removed a tricolour that was flying the heroic episodes of the Irish revolution, it is proper to take there. "Chur rialoffi na Sasana stock and ask where we stand, and where does Ireland stand, and It was pointed out that the city to cause a breach of the peace. criochdheighilt Ho hEireann i what is the road forward to the completion of the work begun was virtually festooned with union bhfeidhm chwi maitheas a n- by Connolly, Pearce, Casement, MacDiarmada, Clarke and count- Jacks, and Mr. MeAteer asked: rsasen they art said to uasaicme fein.'*!. less more. "Did the person who authorised this that the G.A.A. sports We must look fearlessly at the rpHE crux could be put this way: want trouble?" was public property. The A. Jackson. weaknesses and difficulties that be- -*- while England wants to com- was later returned. set the Republican movement, of mit to a consortium of European movai of the Bag was due to a which the Connolly Association is a powers the preservation of the de- part, and at the same time see the pendent ftositlon of such countries \ vast opportunities that lie within as Ireland and her former colonies, our grasp if we are prepared to she is nevertheless anxious to retain think realistically and use what the lion's share of the spoils for E forces exist rather than dream of herself. -

JC445 Causeway Museum Emblems

North East PEACE III Partnership A project supported by the PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by the North East PEACE III Partnership. JJC445C445 CausewayCauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Cover(AW).inddCover(AW).indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:540:54 Badge from the anti-home rule Convention of 1892. Courtesy of Ballymoney Museum. Tourism Poster. emblems Courtesy of Coleraine Museum. ofireland Everywhere we look we see emblems - pictures which immediately conjure connections and understandings. Certain emblems are repeated over and over in a wide range of contexts. Some crop up in situations where you might not expect them. The perception of emblems is not fi xed. Associations change. The early twentieth century was a time when ideas were changing and the earlier signifi cance of certain emblems became blurred. This leafl et contains a few of the better and lesser known facts about these familiar images. 1 JJC445C445 CCausewayauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Inner.inddInner.indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:560:56 TheThe Harp HecataeusHecata of Miletus, the oldest known Greek historian (around 500BC),500BC) describes the Celts of Ireland as “singing songs in praise ofof Apollo,Apo and playing melodiously on the harp”. TheThe harpha has been perceived as the central instrument of ancientancient Irish culture. “The“Th Four Winds of Eirinn”. CourtesyCo of J & J Gamble. theharp The Image of the Harp Harps come in many shapes and sizes. The most familiar form of the Irish harp is based on the so called “Brian Boru’s Harp”. The story is that Brian Boru’s son gave it to the Pope as a penance. -

1 Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland

Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland: Reconciling Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence Eric Kaufmann James Fearon and David Laitin (2003) famously argued that there is no connection between the ethnic fractionalisation of a state’s population and its likelihood of experiencing ethnic conflict. This has contributed towards a general view that ethnic demography is not integral to explaining ethnic violence. Furthermore, sophisticated attempts to probe the connection between ethnic shifts and conflict using large-N datasets have failed to reveal a convincing link. Thus Toft (2007), using Ellingsen's dataset for 1945-94, finds that in world-historical perspective, since 1945, ethno-demographic change does not predict civil war. Toft developed hypotheses from realist theories to explain why a growing minority and/or shrinking majority might set the conditions for conflict. But in tests, the results proved inconclusive. These cross-national data-driven studies tell a story that is out of phase with qualitative evidence from case study and small-N comparative research. Donald Horowitz cites the ‘fear of extinction’ voiced by numerous ethnic group members in relation to the spectre of becoming minorities in ‘their’ own homelands due to differences of fertility and migration. (Horowitz 1985: 175-208) Slack and Doyon (2001) show how districts in Bosnia where Serb populations declined most against their Muslim counterparts during 1961-91 were associated with the highest levels of anti-Muslim ethnic violence. Likewise, a growing field of interest in African studies concerns the problem of ‘autochthony’, whereby ‘native’ groups wreak havoc on new settlers in response to the perception that migrants from more advanced or dense population regions are ‘swamping’ them. -

Legacies of the Troubles and the Holy Cross Girls Primary School Dispute

Glencree Journal 2021 “IS IT ALWAYS GOING BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Eimear Rosato 198 Glencree Journal 2021 Legacy of the Troubles and the Holy Cross School dispute “IS IT ALWAYS GOING TO BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Abstract This article examines the embedded nature of memory and identity within place through a case study of the Holy Cross Girls Primary School ‘incident’ in North Belfast. In 2001, whilst walking to and from school, the pupils of this primary school aged between 4-11 years old, faced daily hostile mobs of unionist/loyalists protesters. These protesters threw stones, bottles, balloons filled with urine, fireworks and other projectiles including a blast bomb (Chris Gilligan 2009, 32). The ‘incident’ derived from a culmination of long- term sectarian tensions across the interface between nationalist/republican Ardoyne and unionist/loyalist Glenbryn. Utilising oral history interviews conducted in 2016–2017 with twelve young people from the Ardoyne community, it will explore their personal experiences and how this event has shaped their identities, memory, understanding of the conflict and approaches to reconciliation. KEY WORDS: Oral history, Northern Ireland, intergenerational memory, reconciliation Introduction Legacies and memories of the past are engrained within territorial boundaries, sites of memory and cultural artefacts. Maurice Halbwachs (1992), the founding father of memory studies, believed that individuals as a group remember, collectively or socially, with the past being understood through ritualism and symbols. Pierre Nora’s (1989) research builds and expands on Halbwachs, arguing that memory ‘crystallises’ itself in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. -

The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel

The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel Edited by Elizabeth Mannion General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14927 Elizabeth Mannion Editor The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel Editor Elizabeth Mannion Philadelphia , Pennsylvania , USA Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-53939-7 ISBN 978-1-137-53940-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-53940-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933996 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or here- after developed. -

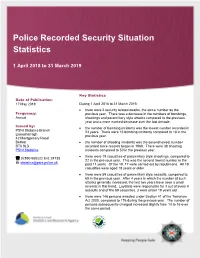

Security Statistics for 2018/19

Police Recorded Security Situation Statistics 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 Key Statistics Date of Publication: 17 May 2019 During 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019: there were 2 security related deaths, the same number as the Frequency: previous year. There was a decrease in the numbers of bombings, Annual shootings and paramilitary style attacks compared to the previous year and a more marked decrease over the last decade. Issued by: the number of bombing incidents was the lowest number recorded in PSNI Statistics Branch 23 years. There were 15 bombing incidents compared to 18 in the Lisnasharragh previous year. 42 Montgomery Road Belfast the number of shooting incidents was the second lowest number BT6 9LD recorded since records began in 1969. There were 38 shooting PSNI Statistics incidents compared to 50 in the previous year. there were 19 casualties of paramilitary style shootings, compared to 02890 650222 Ext. 24135 22 in the previous year. This was the second lowest number in the [email protected] past 11 years. Of the 19, 17 were carried out by republicans. All 19 casualties were aged 18 years or older. there were 59 casualties of paramilitary style assaults, compared to 65 in the previous year. After 4 years in which the number of such attacks generally increased, the last two years have seen a small reversal in this trend. Loyalists were responsible for 3 out of every 4 assaults and of the 59 casualties, 3 were under 18 years old. there were 146 persons arrested under Section 41 of the Terrorism Act 2000, compared to 176 during the previous year. -

David Blevins Your Seat Belt for the Shortest History Lesson David Blevins INTRODUCTION Ever

THE READER A publication of the McCandlish Phillips Journalism Institute Making ‘Hope and History Rhyme’ A talk by David Blevins your seat belt for the shortest history lesson DAvid Blevins INTRODUCTION ever. Patrick had been a slave in Ireland but felt called back, so he returned with What’s the first thing that comes to mind Christianity and education. It’s called “the land when you hear the word: Ireland? Most people of saints and scholars.” When Vikings invaded, think the shamrock is our national symbol. It Ireland sought help from England but the isn’t. The harp is. The colour originally English overstayed their welcome. Cue the associated with Saint Patrick wasn’t green. It charming King Henry the Eighth. He didn’t was blue. And much to our disappointment, have any Irish wives to chop the head off so he everyone isn’t Irish on Saint Patrick’s Day. chopped the head off the Catholic Church TheNorthern Ireland - I’ll explain the difference instead. in a moment – punches way above its weight. Belfast has to be the only city in the world to England crushed Ireland’s resistance, have constructed an entire tourist industry confiscated the land and sent 10,000 Protestant around the fact that it built a ship that sank: Scots to settle in the north. A territorial Titanic. Now, to be fair, of the other ships we dispute had become a religious dispute. That David Blevins, the Ireland launched in the same year, five lasted 30 years, was 800 years in 100 words. Correspondent for Sky News, spoke at nine lasted 50 years and one, the Nomadic, 1916 was the year of the uprising. -

American Blood Ben Sanders

JANUARY 2016 American Blood Ben Sanders A former undercover cop now in witness protection finds himself pulled into the search for a missing woman. An explosive, unputdownable work of suspense from a fresh voice in crime fiction. Description After a botched undercover operation, ex-NYPD officer Marshall Grade is living in witness protection in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Marshall's instructions are to keep a low profile: the mob wants him dead, and a contract killer known as the Dallas Man has been hired to track him down. Racked with guilt over wrongs committed during his undercover work, and seeking atonement, Marshall investigates the disappearance of a local woman named Alyce Ray. Members of a drug ring seem to hold clues to Ray's whereabouts, but hunting traffickers is no quiet task. Word of Marshall's efforts spreads, and soon the worst elements of his former life, including the Dallas Man, are coming for him. Written by a rising New Zealand star who has been described as 'first rate', this American debut drops a Jack Reacher- like hero into the landscape of No Country for Old Men. With film rights sold to Warner Bros, and Bradley Cooper attached to play tortured hero Marshall Grade, American Blood is sure to follow in their award-winning, blockbuster success. 'This novel has it all - great characters that are all too-real, switch-blade sharp writing, dialogue that would bring a smile to Elmore Leonard's face and a plot that grabs the reader by the collar, squeezes hard and never lets go. American Blood is a first-rate, first-class, top-tier thriller and Ben Sanders hits it far and deep. -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

Stuart Neville the Ghosts of Belfast

STUART NEVILLE THE GHOSTS OF BELFAST/THE TWELVE (2009) One of Northern Ireland’s best known and critically reviewed crime writers, Stuart Neville was born in Belfast in 1972. He is the author of seven novels featuring Belfast. His first, The Ghosts of Belfast (published in Ireland as The Twelve) won several awards. His latest, Here and Gone (under the pseudonym Haylen Beck), takes place in Arizona. In the introduction to the anthology, Belfast Noir (Akashic Books 2014), Neville and co-editor Adrian McKinty make the point that during the Troubles Belfast languished culturally. By the time of the 1998 Peace Accord the mystery/crime writers of Northern Ireland had become prominent around the world. Most novels set during the Troubles focus on the effects of the violence on innocent bystanders. Ghosts takes you out of your comfort zone and asks you to deal with characters who are both the cause and perpetrators of the violence. How important is this to understanding the Troubles? Ghosts takes the reader into the psyche of an IRA assassin although the term IRA is never mentioned in the book. Do we feel any sympathy or empathy for Gerry Fegan? Why? Why not? What motivates Fegan to become an IRA hit man? What motivates the double agent Davey Campell? Are the politicians seen as more culpable? Think of the interchange between Fegan and McGinty toward the end of the novel. To what extent does the repeated phrase, “everyone pays, sooner or later,” become a motif in the novel? In a review in The Guardian, Nicola Barr, praises the novel as “a brilliant thriller…Neville has boldly exposed the post-ceasefire Northern Ireland as a confused, contradictory place, a country trying to carve out a future amid a peace recognize by the populace as hypocritical, but accepted as better than the alternative.” While teaching a fiction master class at Armagh, Neville stated that a compulsive plot is not simply a sequence of events but is the inevitable consequences of creating strong characters and allowing them to pursue their conflicting issues. -

Unity Amid Division

Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Unity amid Division The local impact of and response to the Brexit-influenced looming hard border by ordinary citizens in a border city in Northern Ireland Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Credits cover design: Corné van den Boogert Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Wageningen University - Social Sciences Unity Amid Division The local impact of and response to the Brexit-influenced looming hard border by ordinary citizens in a border city in Northern Ireland Student Renée van Abswoude Student number 940201004010 E-mail [email protected] Thesis Supervisor Lotje de Vries Email [email protected] Second reader Robert Coates Email [email protected] University Wageningen University and Research Master’s Program International Development Studies Thesis Chair Group (1) Sociology of Development and Change (2) Disaster Studies Date 20 October 2019 3 Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division “If we keep remembering our past as the implement of how we interrogate our future, things will never change.” - Irish arts officer for the city council, interview 12 April 2019 4 Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Abstract A new language of the Troubles in Northern Ireland dominates international media today. This is especially the case in the city of Derry/Londonderry, where media reported on a car bomb on 19 January 2019, its explosion almost killing five passer-by’s. Only three months later, during Easter, the death of young journalist Lyra McKee shocked the world. International media link these stories to one event that has attracted the eyes of the world: Brexit, and the looming hard border between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. -

The Cold Cold Ground

Cold Cold Ground copy.indd 1 8/21/12 9:37 AM Cold Cold Ground copy.indd 2 8/21/12 9:37 AM 59 John Glenn Drive Amherst, New York 14228–2119 Cold Cold Ground copy.indd 3 8/21/12 9:37 AM Published 2012 by Seventh Street Books™, an imprint of Prometheus Books The Cold Cold Ground. Copyright © 2012 by Adrian McKinty. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopy ing, re cord ing, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, ex cept in the case of brief quotations emb odied in critical articles and reviews. Top cover image © Shutterstock Bottom cover image © AP Photo/PA Cover design by Grace M. Conti-Zilsberger Inquiries should be addressed to Seventh Street Books 59 John Glenn Drive Amherst, New York 14228–2119 VOICE: 716–691–0133 FAX: 716–691–0137 WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM 16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKinty, Adrian. The cold, cold ground : a Detective Sean Duffy novel / by Adrian McKinty. p. cm. “First published: London: Serpent’s Tail, an imprint of Profile Books Ltd., 2012”—T.p. verso. ISBN 978–1–61614–716–7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978–1–61614–717–4 (ebook) 1. Police—Northern Ireland—Fiction. 2. Gay men—Crimes against— Fiction. 3. Catholics—Fiction. 4. Serial murderers—Fiction. 5. Northern Ireland—History—1969–1994—Fiction.