Unity Amid Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARENA Annual Report 2019

ARENA Centre for European Studies University of Oslo Annual report 2019 Introduction ARENA Centre for European Studies is an internationally renowned research centre at the University of Oslo. We conduct theoretically oriented and empirically informed basic research on the dynamics of the evolving European political order. This report provides a comprehensive overview of our ongoing projects, publications and events. 2019 marked ARENA’s 25th anniversary and 25 years since the introduction of the EEA Agreement, a period in which ARENA’s research has shaped both the public and scholarly debate in the field of European studies. This was emphasised at the ARENA anniversary conference by Minister of Foreign Affairs Ine Eriksen Søreide, who congratulated ARENA on its long-time contribution, and underlined the continued need to raise awareness and knowledge about European integration for the future. In 2019 ARENA took on, for the fifth time, the coordinator role on an extensive EU project. EU Differentiation, Dominance and Democracy (EU3D) project members from ARENA will work together with academic partners across Europe to provide new insights on the democratic potentials and pitfalls of differentiation in today’s EU. The project’s kick-off conference in Rome brought together more than 50 participants to discuss differentiation in Europe. ARENA’s many other projects ensured an active year for researchers and staff. GLOBUS organised study tours to China and Russia with partners, policy makers and stakeholder to discuss the EU’s role in the world. PLATO held a fourth PhD School on preliminary project findings. ARENA researchers continued to publish research with top tier academic journals and publishers. -

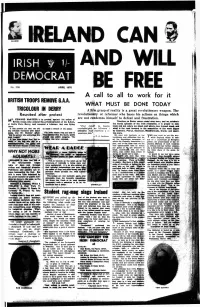

A Call to All to Work for It Wiat MUST BE DONE TODAY

PEARSE CAN CASEMENT WILL No. 308 APRIL 1970 A call to all to work for it BRITISH TROOPS REMOVE G.A.A. WiAT MUST BE DONE TODAY TRICOLOUR IN DERRY A firm grasp of reality is a great revolutionary weapon. The Reunited after protest revolutionary or reformer who bases his actions on things which iiR. EDWARD McATEER is to protest against the action of are not condemns himself to defeat and frustration. m British troops who entered the private grounds of the G.A.A., Therefore as Easter comes round once more, and we celebrate at Celtic Park, Derry, and removed a tricolour that was flying the heroic episodes of the Irish revolution, it is proper to take there. "Chur rialoffi na Sasana stock and ask where we stand, and where does Ireland stand, and It was pointed out that the city to cause a breach of the peace. criochdheighilt Ho hEireann i what is the road forward to the completion of the work begun was virtually festooned with union bhfeidhm chwi maitheas a n- by Connolly, Pearce, Casement, MacDiarmada, Clarke and count- Jacks, and Mr. MeAteer asked: rsasen they art said to uasaicme fein.'*!. less more. "Did the person who authorised this that the G.A.A. sports We must look fearlessly at the rpHE crux could be put this way: want trouble?" was public property. The A. Jackson. weaknesses and difficulties that be- -*- while England wants to com- was later returned. set the Republican movement, of mit to a consortium of European movai of the Bag was due to a which the Connolly Association is a powers the preservation of the de- part, and at the same time see the pendent ftositlon of such countries \ vast opportunities that lie within as Ireland and her former colonies, our grasp if we are prepared to she is nevertheless anxious to retain think realistically and use what the lion's share of the spoils for E forces exist rather than dream of herself. -

Derry - Londonderry

E A L L M D V E A R L R E O A D LE VA Derry - Londonderry ELM OAD AGARDR BALLN ARK P L L D I A H RO N L R IL O H H H Golf Centre T G A ER B Ballyarnett S E Lake S K R R D A C A P A 13 LDER O R D D OAD A R R O TT A R O R G I A E G O N A F H L R A A K L N G I LA Ballyarnett Y K A B V L I LL L G A R B T B A L D A T Wood B R A A I L O D LY E G R O A N G R E R V R E E O E AD W M P D ERAGH H RO A A U B ILL O H RO P L G R D A E IEL P Skeoge K F R L ING E E PR R B S G Industrial A A D L ARK RN L Park KBRIDGE P O IA OA H Thornhill G T H L College R E O N AD A M Ballyarnett O R Country Park F E I R R R O O A A D D A D O K R R E A S P R K U N O A C E B D D N RAC A A M O S AN R SE FI E E L L SANDA D A L EP G A R D OV R K E R N FE L EN E AM K O 13 RE R PA L K R P A A P P E R S E W L D FI O Y A L P K IE L R M R F L T E A P L E H D H T P 12 L S A D A RE E N V O A N O H R E O O E E S O R LA M C O 1 Galliagh W D G H N ’ H R O A L R DO F G St Therese E O N P A R Galliagh O O D AR I E Linear E R N C I K L L D Football A O L E Primary School N O D A A Nursery School R A R D Park E O W A G N G M GroundS LA D K H O P D H O R E T L TE L E R E K A C R E R G A N E LS C O E W E C T R E K A A R O RTLO R O H W O W OP B IN L P NR P A RE L A D OA E R S E D O E E K S N G L A A M A P L A O D E P L N K R L ND U E E R O O MO V K L AP M M C A O DRU S G R EN H RK 11,11A I L C A A LK P I U S A F D T L P L W L B A HI PE E O R H R H K C AIRVIEW ROAD L A OO F O G H 13 R O R R O A R B N G EA EY W G K A R O W R B R L D U A U L R O L A IS C L I C C L L O L O WO A E O I ODB O A -

LE19 - a Turning of the Tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019

#LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Whitten, L. (2019). #LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019. Irish Political Studies, 35(1), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2019.1651294 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Political Studies Association of Ireland.. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 #LE19 – a turning of the tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Lisa Claire Whitten1 Queen’s University Belfast Abstract Otherwise routine local elections in Northern Ireland on 2 May 2019 were bestowed unusual significance by exceptional circumstance. -

JC445 Causeway Museum Emblems

North East PEACE III Partnership A project supported by the PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by the North East PEACE III Partnership. JJC445C445 CausewayCauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Cover(AW).inddCover(AW).indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:540:54 Badge from the anti-home rule Convention of 1892. Courtesy of Ballymoney Museum. Tourism Poster. emblems Courtesy of Coleraine Museum. ofireland Everywhere we look we see emblems - pictures which immediately conjure connections and understandings. Certain emblems are repeated over and over in a wide range of contexts. Some crop up in situations where you might not expect them. The perception of emblems is not fi xed. Associations change. The early twentieth century was a time when ideas were changing and the earlier signifi cance of certain emblems became blurred. This leafl et contains a few of the better and lesser known facts about these familiar images. 1 JJC445C445 CCausewayauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Inner.inddInner.indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:560:56 TheThe Harp HecataeusHecata of Miletus, the oldest known Greek historian (around 500BC),500BC) describes the Celts of Ireland as “singing songs in praise ofof Apollo,Apo and playing melodiously on the harp”. TheThe harpha has been perceived as the central instrument of ancientancient Irish culture. “The“Th Four Winds of Eirinn”. CourtesyCo of J & J Gamble. theharp The Image of the Harp Harps come in many shapes and sizes. The most familiar form of the Irish harp is based on the so called “Brian Boru’s Harp”. The story is that Brian Boru’s son gave it to the Pope as a penance. -

Crossing Derry Crossing Water Always Furthered Something

Simpson.qxd 17/10/2013 09:41 Page 63 63 Crossing Derry Crossing water always furthered something When quoting this line by Seamus Heaney, Martin McGuinness, Northern Ireland’s deputy first minister, registered several points. He was speaking in Derry at a party for volunteers in Fleadh 2013, the all Ireland music festival which was held Tony Simpson ‘north of the border’ for the first time and had attracted some 400,000 visitors to the city during five days in August. Heaney had died a few days after the Fleadh (pronounced ‘fla’), on 30 August. His loss is keenly felt in Derry, where he attended St Columb’s College as a boarder during his early teenage years. There his passion for poetry and flair for Latin and the classics were nurtured. From a small farm in Mossbawn in south County Derry, he had won a scholarship to St Columb’s, courtesy of the 1947 Education in Northern Ireland Act, passed by the Labour Government of the day, as Heaney himself once remarked. Mr McGuinness was acknowledging Seamus Heaney’s profound contribution to civilization and culture, while also addressing Derry’s divisions and how they are being overcome, literally, by the construction of the new Peace Bridge across the River Foyle. He was speaking a few days after visiting Warrington in the north of England, where he had given the peace lecture which we publish in this issue of The Spokesman. Two boys, twelve- years-old Tim Parry and three-years-old Johnathan Ball, had been killed in an IRA bombing in the town in 1993. -

1) Why Was the Outbreak of Violence in Derry ~ Londonderry During The

1) Why was the outbreak of violence in Derry ~ Londonderry during the Battle of the Bogside such a significant event for future violence in Northern Ireland that would be known as The Troubles The Battle of the Bogside was a result of the on-going levels of tension between the Nationalist community in Northern Ireland against the Unionist government and Policing in Northern Ireland at the time. After the events of August 1969 in which the planned NICRA March to Derry was deemed illegal, a counter demonstration by the Apprentice Boys of Derry was planned. Violence flared in the Nationalist Bogside area of Derry in which the security forces struggled to control the violence. Local residents and Nationalists felt that they were struggling to get their concerned addressed and that they faced continued discrimination from the government and the police in their response. 2) Why did the Nationalist Community welcome the arrival of the British Army in the beginning? The Nationalist Community welcomed the arrival of the British Army to Northern Ireland at the beginning as they were seen as protectors from the Loyalist agitators and a more fair form of law and order than they had been used to by the RUC. The British Army were sent into Northern Ireland to restore law and order as well as maintaining good relations with the Nationalist Community, 3) Why were the Unionist Community concerned about the arrival of the British Army to Northern Ireland? The Unionist Community and in particular those within the government and the security forces including the RUC and B-Specials felt that they were being undermined by the British Government and their decision to send the Army to Northern Ireland. -

NEE 2015 2 FINAL.Pdf

ADVERTISEMENT NEW EASTERN EUROPE IS A COLLABORATIVE PROJECT BETWEEN THREE POLISH PARTNERS The City of Gdańsk www.gdansk.pl A city with over a thousand years of history, Gdańsk has been a melting pot of cultures and ethnic groups. The air of tolerance and wealth built on trade has enabled culture, science, and the Arts to flourish in the city for centuries. Today, Gdańsk remains a key meeting place and major tourist attraction in Poland. While the city boasts historic sites of enchanting beauty, it also has a major historic and social importance. In addition to its 1000-year history, the city is the place where the Second World War broke out as well as the birthplace of Solidarność, the Solidarity movement, which led to the fall of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. The European Solidarity Centre www.ecs.gda.pl The European Solidarity Centre is a multifunctional institution combining scientific, cultural and educational activities with a modern museum and archive, which documents freedom movements in the modern history of Poland and Europe. The Centre was established in Gdańsk on November 8th 2007. Its new building was opened in 2014 on the anniversary of the August Accords signed in Gdańsk between the worker’s union “Solidarność” and communist authorities in 1980. The Centre is meant to be an agora, a space for people and ideas that build and develop a civic society, a meeting place for people who hold the world’s future dear. The mission of the Centre is to commemorate, maintain and popularise the heritage and message of the Solidarity movement and the anti-communist democratic op- position in Poland and throughout the world. -

Coleraine and Apprentice Boys | Sample Essay

Coleraine and Apprentice Boys | Sample essay What was the significance of the Coleraine University Controversy and/or the activities of the Apprentice Boys of Derry Both the Coleraine University controversy and the Apprentice Boys of Derry proved to be of great significance in the history of Northern Ireland. Both activities sparked feuds and controversies in the North. While the Apprentice Boys of Derry clearly celebrated Protestant, Unionist beliefs yet people also believed that the Coleraine University was a predominantly Protestant affair. Both the Apprentice Boys of Derry and the Coleraine University controversy are believed to have sparked the significant efforts that were made afterwards to restore peace in Northern Ireland. The Coleraine University Controversy all began when there was a demand for a second university in Northern Ireland. The North’s only university in the 1960’s was Queen’s University. It also had Magee College but degrees could not be completed there. After the Education Act (1947) which entitled more of the Northern Irish population to attend school and further their studies, meant there was a growth in attendance of secondary schools and therefore a demand for third level courses. O Neill’s government was then faced with the decision of either expanding Queens or founding a second university. The Coleraine and Apprentice Boys | Sample essay 1 Lockwood Committee was established in order to reach a decision. This was an eight member committee who enquired the area of third level education. This committee was chaired by Sir John Lockwood the other members were drawn from Northern Ireland. This committee was asked to ‘’review the facilities for university and higher technical education in Northern Ireland having regard to the report of the Robbins Committee and to make recommendations’’. -

Parades and Protests – an Annotated Bibliography

P a Parades and Protests r a d e An Annotated Bibliography s a n d P r o t e s t s - A n A n n o t This publication reviews all the major policy documents, community a t publications, academic papers and books that focus on the contemporary e culture of parading and the current cycle of protests related to parades in d Northern Ireland. It provides an outline of discussion and analysis contained in B i nearly ninety documents that have been published since 1982. This annotated b l bibliography will be a valuable resource for community groups and i o organisations working on the subject of parades and associated issues as well as g r for policy makers, researchers and academics. a p h y J Institute for Conflict Research o h North City Business Centre n B 2 Duncairn Gardens, e l Belfast BT15 2GG l Northern Ireland John Bell ISBN 978-0-9552259-3-2 Telephone: +44 (0)28 9074 2682 Fax: +44 (0)28 9035 6654 £5 2903IC~1.QXD:1417 ICR Migrant 5/10/07 14:58 Page 1 Parades and Protests An Annotated Bibliography John Bell Institute for Conflict Research 2903IC~1.QXD:1417 ICR Migrant 5/10/07 14:58 Page 2 Parades and Protests, an Annotated Bibliography First Published October 2007 Institute for Conflict Research North City Business Centre 2 Duncairn Gardens Belfast BT15 2GG Tel: +44 (0)28 9074 2682 Email: [email protected] Web: www.conflictresearch.org.uk Belfast Interface Project Third Floor 109-113 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF Tel: +44 (0)28 9024 2828 Email: [email protected] Web: www.belfastinterfaceproject.org ISBN: 978-0-9552259-3-2 This project has been funded through the Belfast City Council Good Relations Programme Unit and the Community Relations Council. -

Debates Posėdžio Stenograma

2014 - 2019 ПЪЛЕН ПРОТОКОЛ НА РАЗИСКВАНИЯТА DEBAŠU STENOGRAMMA ACTA LITERAL DE LOS DEBATES POSĖDŽIO STENOGRAMA DOSLOVNÝ ZÁZNAM ZE ZASEDÁNÍ AZ ÜLÉSEK SZÓ SZERINTI JEGYZŐKÖNYVE FULDSTÆNDIGT FORHANDLINGSREFERAT RAPPORTI VERBATIM TAD-DIBATTITI AUSFÜHRLICHE SITZUNGSBERICHTE VOLLEDIG VERSLAG VAN DE VERGADERINGEN ISTUNGI STENOGRAMM PEŁNE SPRAWOZDANIE Z OBRAD ΠΛΗΡΗ ΠΡΑΚΤΙΚΑ ΤΩΝ ΣΥΖΗΤΗΣΕΩΝ RELATO INTEGRAL DOS DEBATES VERBATIM REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS STENOGRAMA DEZBATERILOR COMPTE RENDU IN EXTENSO DES DÉBATS DOSLOVNÝ ZÁPIS Z ROZPRÁV TUARASCÁIL FOCAL AR FHOCAL NA N-IMEACHTAÍ DOBESEDNI ZAPISI RAZPRAV DOSLOVNO IZVJEŠĆE SANATARKAT ISTUNTOSELOSTUKSET RESOCONTO INTEGRALE DELLE DISCUSSIONI FULLSTÄNDIGT FÖRHANDLINGSREFERAT Сряда - Miércoles - Středa - Onsdag - Mittwoch - Kolmapäev - Τετάρτη - Wednesday Mercredi - Dé Céadaoin - Srijeda - Mercoledì - Trešdiena - Trečiadienis - Szerda L-Erbgħa - Woensdag - Środa - Quarta-feira - Miercuri - Streda - Sreda - Keskiviikko - Onsdag 01.03.2017 Единство в многообразието - Unida en la diversidad - Jednotná v rozmanitosti - Forenet i mangfoldighed - In Vielfalt geeint - Ühinenud mitmekesisuses Eνωμένη στην πολυμορφία - United in diversity - Unie dans la diversité - Aontaithe san éagsúlacht - Ujedinjena u raznolikosti - Unita nella diversità Vienoti daudzveidībā - Susivieniję įvairovėje - Egyesülve a sokféleségben - Magħquda fid-diversità - In verscheidenheid verenigd - Zjednoczona w różnorodności Unida na diversidade - Unită în diversitate - Zjednotení v rozmanitosti - Združena v raznolikosti - Moninaisuudessaan yhtenäinen -

50 Years Since the Battle of the Bogside in Derry

Séquence 2 Public cible 2de, cycle terminal, post-bac / Écouter : A2 à B2 ; Écrire : B1/B2 50 years since the Battle of the Bogside in Derry Ce reportage est consacré aux 50 ans des trois jours d’émeutes opposant la population catholique du Bogside, un quartier de Londonderry, à la police royale de l’Ulster (RUC) connus sous le nom de la Bataille du Bogside. Une marche des Apprentice Boys of Derry provoqua la colère des catholiques, qui donna lieu à des affrontements de plus en plus violents avec la police. Cette escalade de violence entraîna l’arrivée des premières troupes britanniques en Irlande du Nord. Transcript TV host: It’s 50 years today since the beginning of the Battle of the Bogside which saw three days of rioting in Derry. The violence sparked further unrest and led to the deployment of British troops to Northern Ireland for the first time since partition. Voice-over (journalist): Tensions had been rising across Northern Ireland at least a year before a contentious Apprentice Boys parade took place in Derry on the twelfth of August 1969. Community leaders had called for the march to be cancelled amidst nationalist claims of bias within the RUC and widespread discrimination. As the bands passed the Catholic Bogside area of the city protesters threw stones and other missiles. It led to three days of fierce clashes with the police who were accused of being heavy handed. Activist Eamonn McCann was among the protesters in the Bogside. He says the events of those few days still resonate 50 years on.