Jane Pettegree Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

16Th and 17Th Century Books

Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books 1 Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books 2 Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century books 3 Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books Catalogue 9 – Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century books Antiquates Ltd The Conifers Valley Road Corfe Castle Dorset BH20 5HU United Kingdom tel: 07921 151496 email: [email protected] web: www.antiquates.co.uk twitter: @TomAntiquates Payment to be made by cheque or bank transfer, institutions can be billed. Alternative currencies can be accommodated. Postage and packaging costs will be added to orders. All items offered subject to prior sale. E. & O.E. All items remain the legal property of the seller until paid for in full. Inside front cover: 91 Inside rear cover: 100 Rear cover: 3 Antiquates Ltd is Registered in England and Wales No: 6290905 Registered Office: As above VAT Reg. No. GB 942 4835 11 4 Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books AN APOTHECARY'S BAD END 1) ABBOT, Robert. The Young Mans Warning-piece. Or, A Sermon preached at the burial of Williams Rogers. Apothecary. With an History of his sinful Life, and Woful Death. Together with a Post-script of the use of Examples. Dedicated to the young Men of the Parish, especially to his Companions. London. Printed by J.R. for John Williams, 1671. 12mo. [20], 76, 79-102pp. Recent antique-style blind-ruled calf, contrasting morocco title-label, gilt, to upper board. New endpapers. Marginal chipping, marking and signs of adhesion to preliminaries. With manuscript biographical notes on William Rogers to title, and the inscription of Edward Perronet to verso: 'The gift of Mr Thos. -

Edward De Vere and the Two Shrew Plays

The Playwright’s Progress: Edward de Vere and the Two Shrew Plays Ramon Jiménez or more than 400 years the two Shrew plays—The Tayminge of a Shrowe (1594) and The Taming of the Shrew (1623)—have been entangled with each other in scholarly disagreements about who wrote them, which was F written first, and how they relate to each other. Even today, there is consensus on only one of these questions—that it was Shakespeare alone who wrote The Shrew that appeared in the Folio . It is, as J. Dover Wilson wrote, “one of the most diffi- cult cruxes in the Shakespearian canon” (vii). An objective review of the evidence, however, supplies a solution to the puz- zle. It confirms that the two plays were written in the order in which they appear in the record, The Shrew being a major revision of the earlier play, A Shrew . They were by the same author—Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, whose poetry and plays appeared under the pseudonym “William Shakespeare” during the last decade of his life. Events in Oxford’s sixteenth year and his travels in the 1570s support composition dates before 1580 for both plays. These conclusions also reveal a unique and hitherto unremarked example of the playwright’s progress and development from a teenager learning to write for the stage to a journeyman dramatist in his twenties. De Vere’s exposure to the in- tricacies and language of the law, and his extended tour of France and Italy, as well as his maturation as a poet, caused him to rewrite his earlier effort and pro- duce a comedy that continues to entertain centuries later. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Fasig-Tipton

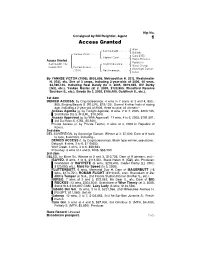

Hip No. Consigned by Bill Reightler, Agent 1 Access Granted Halo Saint Ballado . { Ballade Yankee Victor . Caro (IRE) { Highest Carol . { Tokyo Princess Access Granted . Fappiano Dark bay/br. filly; Cryptoclearance . { Naval Orange foaled 2002 {Denied Access . Sovereign Dancer (1992) { Del Sovereign . { Delso By YANKEE VICTOR (1996), $833,806, Metropolitan H. [G1], Westchester H. [G3], etc. Sire of 3 crops, including 2-year-olds of 2006, 40 wnrs, $2,490,140, including Real Dandy (to 3, 2005, $819,935, WV Derby [G3], etc.), Yankee Master (at 2, 2005, $123,900, Woodford Reserve Bourbon S., etc.), Swede (to 3, 2005, $106,400, Goldfinch S., etc.). 1st dam DENIED ACCESS, by Cryptoclearance. 4 wins in 7 starts at 3 and 4, $53,- 865, Singing Beauty S. [R] (LRL, $19,125). Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2006, three to race, all winners-- Access Agenda (g. by Twilight Agenda). 8 wins, 2 to 7, 2005, $203,735, 2nd Mister Diz S.-R (LRL, $10,000). Access Approved (g. by With Approval). 11 wins, 4 to 6, 2005, $181,591, 3rd Da Hoss S. (CNL, $5,500). Private Access (c. by Private Terms). 2 wins at 4, 2005 in Republic of Korea. 2nd dam DEL SOVEREIGN, by Sovereign Dancer. Winner at 2, $7,500. Dam of 9 foals to race, 8 winners, including-- DENIED ACCESS (f. by Cryptoclearance). Black type winner, see above. Delquoit. 8 wins, 2 to 6, $119,653. Wolf Creek. 4 wins, 3 to 6, $58,683. Provobay. 3 wins at 4 and 5, 2005, $55,900. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

Heracles on Top of Troy in the Casa Di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii Katharina Lorenz

9 | Split-screen visions: Heracles on top of Troy in the Casa di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii katharina lorenz The houses of Pompeii are full of mythological images, several of which present scenes of Greek, few of Roman epic.1 Epic visions, visual experi- ences derived from paintings featuring epic story material, are, therefore, a staple feature in the domestic sphere of the Campanian town throughout the late first century BCE and the first century CE until the destruction of the town in 79 CE. The scenes of epic, and mythological scenes more broadly, profoundly undercut the notion that such visualisations are merely illustration of a textual manifestation; on the contrary: employing a diverse range of narrative strategies and accentuations, they elicit content exclusive to the visual domain, and rub up against the conventional, textual classifications of literary genres. The media- and genre-transgressing nature of Pompeian mythological pictures renders them an ideal corpus of material to explore what the relationships are between visual representations of epic and epic visions, what characterises the epithet ‘epic’ when transferred to the visual domain, and whether epic visions can only be generated by stories which the viewer associates with a text or texts of the epic genre. One Pompeian house in particular provides a promising framework to study this: the Casa di Octavius Quartio, which in one of its rooms combines two figure friezes in what is comparable to the modern cinematographic mode of the split screen. Modern study has been reluctant to discuss these pictures together,2 1 Vitruvius (7.5.2) differentiates between divine, mythological and Homeric decorations, emphasising the special standing of Iliad and Odyssey in comparison to the overall corpus of mythological depictions; cf. -

Det. 1.2.2 Quartos 1594-1609.Pdf

author registered year of title printer stationer value editions edition Anon. 6 February 1594 to John 1594 The most lamentable Romaine tragedie of Titus Iohn Danter Edward White & "rather good" 1600, 1611 Danter Andronicus as it was plaide by the Right Honourable Thomas Millington the Earle of Darbie, Earle of Pembrooke, and Earle of Sussex their seruants Anon. 2 May 1594 1594 A Pleasant Conceited Historie, Called the Taming of Peter Short Cuthbert Burby bad a Shrew. As it was sundry times acted by the Right honorable the Earle of Pembrook his seruants. Anon. 12 March 1594 to Thomas 1594 The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Thomas Creede Thomas Millington bad 1600 Millington Famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster . [Henry VI Part 2] Anon. 1595 The true tragedie of Richard Duke of York , and P. S. [Peter Short] Thomas Millington bad 1600 the death of good King Henrie the Sixt, with the whole contention betweene the two houses Lancaster and Yorke, as it was sundrie times acted by the Right Honourable the Earle of Pembrooke his seruants [Henry VI Part 3] Anon. 1597 An excellent conceited tragedie of Romeo and Iuliet. Iohn Danter [and bad As it hath been often (with great applause) plaid Edward Allde] publiquely, by the Right Honourable the L. of Hunsdon his seruants Anon. 29 August 1597 to Andrew 1597 The tragedie of King Richard the second. As it hath Valentine Simmes Andrew Wise "rather good" Wise been publikely acted by the Right Honourable the Lorde Chamberlaine his seruants. William Shake-speare [29 Aug 1597] 1598 The tragedie of King Richard the second. -

Cliffs Complete Shakespeare's Macbeth

8572-X_3 fm 11/29/01 4:19 PM Page i CLIFFSCOMPLETE Shakespeare’s Macbeth Edited by Sidney Lamb Associate Professor of English Sir George Williams University, Montreal Complete Text + Commentary + Glossary Commentary by Christopher L. Morrow Best-Selling Books • Digital Downloads • e-Books • Answer Networks • e-Newsletters • Branded Web Sites • e-Learning New York, NY • Cleveland, OH • Indianapolis, IN 8572-X FM.F 4/17/00 8:11 AM Page ii 8572-X FM.F 4/17/00 8:11 AM Page iii CLIFFSCOMPLETE Shakespeare’s Macbeth 8572-X_3 fm 11/29/01 4:19 PM Page iv About the Author Publisher’s Acknowledgments Christopher L. Morrow is currently a doctoral student at Texas A&M Uni- Editorial versity where he is working on a dissertation in Early Modern drama. Mor- Project Editor: Joan Friedman row received his Bachelor of Arts from the University of Wyoming in 1996 Acquisitions Editor: Gregory W. Tubach and his Master of Arts from Texas A&M University in 1998. He is also Copy Editor: Billie A. Williams currently a graduate assistant with the World Shakespeare Bibliography as Editorial Manager: Kristin A. Cocks well as a volunteer graduate assistant with the Seventeenth-Century News. Illustrator: DD Dowden Special Help: Patricia Yuu Pan Production Indexer: Sharon Hilgenberg Proofreader: Rachel Garvey Hungry Minds Indianapolis Production Services CliffsComplete Macbeth Published by Note: If you purchased this book without a cover you Hungry Minds, Inc. should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was 909 Third Avenue reported as "unsold and destroyed" to the publisher, and New York, NY 10022 neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this "stripped book." www.hungryminds.com www.cliffsnotes.com (CliffsNotes Web site) Copyright © 2000 Hungry Minds, Inc. -

Pagan Fictions: Literature and False Religion in England, 1550–1650

Pagan Fictions: Literature and False Religion in England, 1550–1650 Joseph Wallace A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Reid Barbour Jessica Wolfe Megan Matchinske Mary Floyd-Wilson Robert Babcock ©2013 Joseph Wallace ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JOSEPH WALLACE: Pagan Fictions: Literature and False Religion in England, 1550–1650 (Under the direction of Reid Barbour and Jessica Wolfe) This dissertation represents an effort to rethink one of the defining problems of the European Renaissance: the revival of pagan culture. It was very common for Renaissance Christians, from Giovanni Boccaccio to John Calvin, to argue that pagan religions were false because they were based on myths created by poets and politicians. But the Reformation project of distinguishing true from false versions of Christian religion blurred the boundaries between ancient and more recent versions of false religion. The hinge of this reorientation of religious values was the argument that certain religions were merely poetic fables, artificial fictions created by humans. And while some scholars have discussed the changing meaning of religion in the seventeenth century, no one has seen that literary language provided the terms for this change. My project corrects this by juxtaposing the religious imagery of the poetry of Robert Herrick, John Milton, and many others with contemporary debates about the poetic nature of religious imagery. In this way, my project makes a unique contribution to Renaissance studies by demonstrating not only that literary categories are fundamental to an understanding of religion, but also that the religious revolution of the Reformation produced lasting changes in how literary texts create meaning. -

The Greek College at Oxford, 1699-1705

The Greek College at Oxford, 1699-1705 By E. D. TAPPE INTRODUCTION HERE has perhaps never been a time since the Reformation when some T group in the Anglican Church has not been exploring the possibility of a rapprochement with some section of the Orthodox Church. In particular during the seventeenth century and the first quarter of the eighteenth, Anglicans showed considerable interest in the Greek Church, and this interest was re ciprocated.' In 1616 Cyril Lucaris, then Patriarch of Alexandria, commended a young priest, Metrophanes Critopoulos, to the Archbishop of Canterbury. At his own expense the Archbishop, George Abbot, sent Metrophanes to Oxford, to study theology at Ballio!. On his return to the East, Metrophanes, in spite of an adverse report from Abbot, continued to enjoy the favour of Cyril Lucaris and rose to be, in his turn, Patriarch of Alexandria. That Metrophanes was not the only Greek anxious to study in England at that time is shown, for instance, by an appeal made in 1621 to the King, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London by two others, Gregory, Archimandrite of Mace donia, and Katakouzenos, who asked to be sent to Oxford to study philosophy and theology.' The period of the Civil War and the Commonwealth was as unpropitious for cultural relations with the Greek Orthodox Church as it was for commerce in the Levant. Nathaniel Conopius, another protege of Lucaris, who ned from Constantinople when his patron was murdered, was also at Balliol, and was expelled from there by the Puritans in 1648. His chief claim on the gratitude of Oxonians is that, according to the diarist Evelyn, he was the first man to drink collec in Oxford.