Creating a Tatar Capital: National, Cultural, and Linguistic Space in Kazan, 1920-1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Programme

FINAL PROGRAMME Friday, 12 June 2015 8.00-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.30 Welcome Address/Opening ceremony Chairs: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) Minister of health of the Republic of Lithuania (Vilnius, Lithuania) Rector of Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Dean of the Faculty of Medicine Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania) Director of the Nacional Cancer Institute (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30 – 11.00 SESSION I Chairs: J. Niklinski (Bialystok, Poland), K. Sužiedėlis (Vilnius, Lithuania) 9.30-11.00 Bialystok Medical Academy – Research Group (Bialystok, Poland) Chairs: Prof. Jacek Niklinski, Prof. Lech Chyczewski Immune system and lung cancer: friends or foes? M. Moniuszko Science fiction or science reality - microRNA replacement therapy Anna Rusek The role of transcription factor Sox2 in cancer biology A. Eljaszewicz Recent guidelines for the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer- diagnostic challenges and problems J. Reszec Metabolomic profiling of non-small cell lung cancer J. Kisluk 11.00 - 11.30 Lung cancer in women and never smokers S. Novello (Turin, Italy) 11.30 - 12.00 Coffee break 12.00 –13.00 AstraZeneca Satellite Symposium Chair: S. Cicėnas (Vilnius, Lithuania) 13.00-14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 16.40 Scientific session II Chairs: R. Pirker (Vienna, Austria), E. Danila (Vilnius, Lithuania). 14.00-14.40 Bevacizumab in treatment of NSCLC: preferred chemo partners F. De Marinis (Milan, Italy) 14.40-15.00 Lung Cancer Screening – Radiological Opportunities and Challenges S. Sudarski (Mannheim, Germany) 15.00-15.20 Tobacco control strategies M. Neuberger (Vienna, Austria) 15.20-15.40 Lung cancer screening by spiral CT M. Silva (Milano, Italy) 15.40-16.00 Biomarkers for chemotherapy in NSCLC J.B. -

Toponimys with Ancient Turk Origins in the Balkans

IBAC 2012 vol.2 TOPONIMYS WITH ANCIENT TURK ORIGINS IN THE BALKANS Prof .Ass. Hajiyeva GALIBA Nakhchivan State Univresity, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract One of the sources dealing with the ancient Turkic history are toponyms. Toponymic investigations show that most of the ancient geographical names which have spread in Eurosia, in Central Asia, from North Africa, to Eastern Turkistan even in Siberia and these names were formed before Roman and Byzantine periods. So development of toponymic investigations, study of the history of Turkic peoples and scientific investigation of existing geographical names which keep the history of Turkic peoples have great significance. One of the uninvestigated fields of the Turkic history are geographical names keeping historical facts within are the holy Balkan areas. The toponymic investigations carried on the Balkans show that these territories are the places were the ancient Turkic tribes were firstly settled and possessed. This fact is proved by the Turkic tribe names and by the words of different semantic meaning of the languages of Turkic tribes. The great deal of Balkan geographical names are the names derived out of ethnoniyms thus the names reflecting ancient Turkic tribe names (Astipos//Astepe//Ishtip, Izletdere, Vardar, Sofular, Gilan, Sahsuvar kariyesi, Kosalar village, Tatarli kariyesi, in the Kosova, Uskup, Usturumca, Kumanova, Propishtip, Kochana, Makedonska Kamenika in Makedony, Araz district, Arazli, Azman, Cepine, Coban, Chorlu, Culfalar, Horozlar, Kangirlar, Sakarli, Sungurlar, Karuk, Kaspi, Kaz//Kas, Kazancilar, Kecililer, Kuman, Padarlar, Sofular, Tatar, Uzlar in Bulgaria) show that Balkans historically were Turkic areas. Geographical names are the real witnesses of history. We must pay great attention to the scientific investigations of the geographical names in Balkan states. -

Guide to Investment Volume 8

Guide to investment Volume 8. Republic of Tatarstan Guide to investment PricewaterhouseCoopers provides industry-focused assurance, tax and advisory services to build public trust and enhance value for its clients and their stakeholders. More than 163,000 people in 151 countries work collaboratively using connected thinking to develop fresh perspectives and practical advice. PricewaterhouseCoopers first appeared in Russia in 1913 and re-established its presence here in 1989. Since then, PricewaterhouseCoopers has been a leader in providing professional services in Russia. According to the annual rating published in Expert magazine, PricewaterhouseCoopers is the largest audit and consulting firm in Russia (see Expert, 2000-2009). This overview has been prepared in conjunction with and based on the materials provided by the Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Tatarstan. This publication has been prepared for general guidance on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and, to the extent permitted by law, PricewaterhouseCoopers, its members, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or -

Implementation of the Selective Strategy of State

Periódico do Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas sobre Gênero e Direito Centro de Ciências Jurídicas - Universidade Federal da Paraíba V. 8 - Nº 04 - Ano 2019 – Special Edition ISSN | 2179-7137 | http://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs2/index.php/ged/index 156 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SELECTIVE STRATEGY OF STATE REGULATION OF THE LABOUR MARKET IN TERMS OF MONOPROPELLANT SITE (ON EXAMPLE OF THE CHISTOPOLSKY MUNICIPAL AREA) Irina V. Yusupova1 Leilia R. Kadyrova2 Abstract: The article is devoted to the organization of public works, as well as implementation of selective (mixed) vocational training and training of strategy of state regulation of the labor unemployed citizens, including disabled market in terms of monopropellant areas, people, persons without a profession, as involving constant monitoring of the well as women with children under the labor market areas, the adoption of age of 3 years, is an established activity operational measures in the field of aimed at practically guaranteed reducing unemployment and increasing employment of these categories of employment, as well as selective people. At the same time, an effective screening workforce. In conditions of mechanism for implementing selective non-diversified economy of the territory (mixed) strategies is the outstripping the problems of employment and training of people who are at risk of mass unemployment are particularly acute and dismissal (lockout) from enterprises and require an additional set of measures to organizations. reduce labor market difficulties. The state regulation of the labor market in the Keywords: human capital, labour Russian Federation in terms of providing resources, a selective strategy, employment and reducing the overall government regulation, labor market, and registered unemployment rates has human resources, non-diversified more than a 25-year history. -

THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY of the BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' Iosfery)

XA04N2887 INIS-XA-N--259 L.A. Pertsov TRANSLATED FROM RUSSIAN Published for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations L. A. PERTSOV THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' iosfery) Atomizdat NMoskva 1964 Translated from Russian Israel Program for Scientific Translations Jerusalem 1967 18 02 AEC-tr- 6714 Published Pursuant to an Agreement with THE U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION and THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, WASHINGTON, D. C. Copyright (D 1967 Israel Program for scientific Translations Ltd. IPST Cat. No. 1802 Translated and Edited by IPST Staff Printed in Jerusalem by S. Monison Available from the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Va. 22151 VI/ Table of Contents Introduction .1..................... Bibliography ...................................... 5 Chapter 1. GENESIS OF THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE ......................... 6 § Some historical problems...................... 6 § 2. Formation of natural radioactive isotopes of the earth ..... 7 §3. Radioactive isotope creation by cosmic radiation. ....... 11 §4. Distribution of radioactive isotopes in the earth ........ 12 § 5. The spread of radioactive isotopes over the earth's surface. ................................. 16 § 6. The cycle of natural radioactive isotopes in the biosphere. ................................ 18 Bibliography ................ .................. 22 Chapter 2. PHYSICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF NATURAL RADIOACTIVE ISOTOPES. ........... 24 § 1. The contribution of individual radioactive isotopes to the total radioactivity of the biosphere. ............... 24 § 2. Properties of radioactive isotopes not belonging to radio- active families . ............ I............ 27 § 3. Properties of radioactive isotopes of the radioactive families. ................................ 38 § 4. Properties of radioactive isotopes of rare-earth elements . -

Annual Report of the Tatneft Company

LOOKING INTO THE FUTURE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TATNEFT COMPANY ABOUT OPERATIONS CORPORATE FINANCIAL SOCIAL INDUSTRIAL SAFETY & PJSC TATNEFT, ANNUAL REPORT 2015 THE COMPANY MANAGEMENT RESULTS RESPONSIBILITY ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY CONTENTS ABOUT THE COMPANY 01 Joint Address to Shareholders, Investors and Partners .......................................................................................................... 02 The Company’s Mission ....................................................................................................................................................... 04 Equity Holding Structure of PJSC TATNEFT ........................................................................................................................... 06 Development and Continuity of the Company’s Strategic Initiatives.......................................................................................... 09 Business Model ................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Finanical Position and Strengthening the Assets Structure ...................................................................................................... 12 Major Industrial Factors Affecting the Company’s Activity in 2015 ............................................................................................ 18 Model of Sustainable Development of the Company .............................................................................................................. -

The Axis Advances

wh07_te_ch17_s02_MOD_s.fm Page 568 Monday, March 12, 2007 2:32WH07MOD_se_CH17_s02_s.fm PM Page 568 Monday, January 29, 2007 6:01 PM Step-by-Step German fighter plane SECTION Instruction 2 WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO Objectives Janina’s War Story As you teach this section, keep students “ It was 10:30 in the morning and I was helping my focused on the following objectives to help mother and a servant girl with bags and baskets as them answer the Section Focus Question they set out for the market. Suddenly the high- and master core content. pitch scream of diving planes caused everyone to 2 freeze. Countless explosions shook our house ■ Describe how the Axis powers came to followed by the rat-tat-tat of strafing machine control much of Europe, but failed to guns. We could only stare at each other in horror. conquer Britain. Later reports would confirm that several German Janina Sulkowska in ■ Summarize Germany’s invasion of the the early 1930s Stukas had screamed out of a blue sky and . Soviet Union. dropped several bombs along the main street— and then returned to strafe the market. The carnage ■ Understand the horror of the genocide was terrible. the Nazis committed. —Janina Sulkowska,” Krzemieniec, Poland, ■ Describe the role of the United States September 12, 1939 before and after joining World War II. Focus Question Which regions were attacked and occupied by the Axis powers, and what was life like under their occupation? Prepare to Read The Axis Advances Build Background Knowledge L3 Objectives Diplomacy and compromise had not satisfied the Axis powers’ Remind students that the German attack • Describe how the Axis powers came to control hunger for empire. -

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

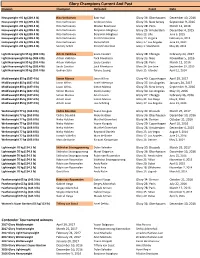

Glory Champions Current and Past Division Champion Defeated Event Date

Glory Champions Current And Past Division Champion Defeated Event Date Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Badr Hari Glory 36: Oberhausen December 10, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Anderson Silva Glory 33: New Jersey September 9, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Mladen Brestovac Glory 28: Paris March 12, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Benjamin Adegbuyi Glory 26: Amsterdam December 4, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Benjamin Adegbuyi Glory 22: Lille June 5, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Errol Zimmerman Glory 19: Virginia February 6, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Daniel Ghiță Glory 17: Los Angeles June 21, 2014 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Semmy Schilt Errol Zimmerman Glory 1: Stockholm May 26, 2012 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Saulo Cavalari Glory 38: Chicago February 24, 2017 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Zack Mwekassa Glory 35: Nice November 5, 2016 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Saulo Cavalari Glory 28: Paris March 12, 2016 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Saulo Cavalari Zack Mwekassa Glory 24: San Jose September 19, 2015 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Gökhan Saki Tyrone Spong Glory 15: Istanbul April 12, 2014 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Simon Marcus Jason Wilnis Glory 40: Copenhagen April 29, 2017 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Jason Wilnis Israel Adesanya Glory 37: Los Angeles January 20, 2017 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Jason Wilnis Simon Marcus -

Governance on Russia's Early-Modern Frontier

ABSOLUTISM AND EMPIRE: GOVERNANCE ON RUSSIA’S EARLY-MODERN FRONTIER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Paul Romaniello, B. A., M. A. The Ohio State University 2003 Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Eve Levin, Advisor Dr. Geoffrey Parker Advisor Dr. David Hoffmann Department of History Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle ABSTRACT The conquest of the Khanate of Kazan’ was a pivotal event in the development of Muscovy. Moscow gained possession over a previously independent political entity with a multiethnic and multiconfessional populace. The Muscovite political system adapted to the unique circumstances of its expanding frontier and prepared for the continuing expansion to its east through Siberia and to the south down to the Caspian port city of Astrakhan. Muscovy’s government attempted to incorporate quickly its new land and peoples within the preexisting structures of the state. Though Muscovy had been multiethnic from its origins, the Middle Volga Region introduced a sizeable Muslim population for the first time, an event of great import following the Muslim conquest of Constantinople in the previous century. Kazan’s social composition paralleled Moscow’s; the city and its environs contained elites, peasants, and slaves. While the Muslim elite quickly converted to Russian Orthodoxy to preserve their social status, much of the local population did not, leaving Moscow’s frontier populated with animists and Muslims, who had stronger cultural connections to their nomadic neighbors than their Orthodox rulers. The state had two major goals for the Middle Volga Region. -

Ukraine in World War II

Ukraine in World War II. — Kyiv, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, 2015. — 28 p., ill. Ukrainians in the World War II. Facts, figures, persons. A complex pattern of world confrontation in our land and Ukrainians on the all fronts of the global conflict. Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Address: 16, Lypska str., Kyiv, 01021, Ukraine. Phone: +38 (044) 253-15-63 Fax: +38 (044) 254-05-85 Е-mail: [email protected] www.memory.gov.ua Printed by ПП «Друк щоденно» 251 Zelena str. Lviv Order N30-04-2015/2в 30.04.2015 © UINR, texts and design, 2015. UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE www.memory.gov.ua UKRAINE IN WORLD WAR II Reference book The 70th anniversary of victory over Nazism in World War II Kyiv, 2015 Victims and heroes VICTIMS AND HEROES Ukrainians – the Heroes of Second World War During the Second World War, Ukraine lost more people than the combined losses Ivan Kozhedub Peter Dmytruk Nicholas Oresko of Great Britain, Canada, Poland, the USA and France. The total Ukrainian losses during the war is an estimated 8-10 million lives. The number of Ukrainian victims Soviet fighter pilot. The most Canadian military pilot. Master Sergeant U.S. Army. effective Allied ace. Had 64 air He was shot down and For a daring attack on the can be compared to the modern population of Austria. victories. Awarded the Hero joined the French enemy’s fortified position of the Soviet Union three Resistance. Saved civilians in Germany, he was awarded times. from German repression. the highest American The Ukrainians in the Transcarpathia were the first during the interwar period, who Awarded the Cross of War. -

(+232 Lbs ) KINGS of the RING WORLD SERIES

OPEN SUPER HEAVYWEIGHT +105 kg (+232 lbs ) Japanese boxing - Shootboxing rules Super world champion Date, Place VACANT 14 World champion Date, Place VACANT Thai boxing - Full muaythai rules Thai boxing - International muaythai rules SUPER WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place SUPER WORLD CHAMPION Date, place VACANT VACANT WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place 09.02.2008 LLOYD VAN DAMS ( NL ) 29.05.2004 TONY GREGORY ( FRA ) Auckland- = 289 pts Venice-ITA = 413 pts NZ OPBU EURO-AFRICAN CHAMPION Date, Place OPBU EURO-AFRICAN CHAMPION Date, Place VACANT VACANT Japanese boxing - K -1 rules Japanese boxing - Oriental Kick rules SUPER WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place SUPER WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place VACANT VACANT WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place WORLD CHAMPION Date, Place VACANT VACANT OPBU EURO-AFRICAN CHAMPION Date, Place OPBU EURO-AFRICAN CHAMPION Date, Place VACANT VACANT KINGS OF THE RING WORLD SERIES WIPU ORIENTAL PRO BOXING RULES SUPER WORLD CHAMPION Date, place VACANT e-mail : [email protected] mobile phone : +385 98 421 300 www.wipu-kings.com OPEN SUPER HEAVYWEIGHT +105 kg (+232 lbs ) 1. Semmy Schilt ( NL ) = 964 pts 2. Peter Aerts ( NL ) = 645 pts 3. Jerome Lebanner ( FRA ) = 571 pts 4. Alistar Overeem ( NL ) = 524 pts 5. Alexei Ignashov ( BLR ) = 432 pts 6. Daniel Ghita ( ROM ) = 362 pts 7. '' MIGHTY MO '' Siligia ( USA ) = 362 pts 8. Anderson '' Bradock '' Silva ( BRA ) = 344 pts 9. Mladen Brestovac ( CRO ) = 311 pts 10. Ismael Londt ( NL ) = 290 pts 11. Rico Verhoeven ( NL ) = 275 pts 12. Ben Edwards ( AUS ) = 258 pts 13. Peter Graham ( AUS ) = 243 pts 14. Alexandre Pitchkounov ( RUS ) = 236 pts 15.