A Basic Introduction to Criminal Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Police Misconduct As a Cause of Wrongful Convictions

POLICE MISCONDUCT AS A CAUSE OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS RUSSELL COVEY ABSTRACT This study gathers data from two mass exonerations resulting from major police scandals, one involving the Rampart division of the L.A.P.D., and the other occurring in Tulia, Texas. To date, these cases have received little systematic attention by wrongful convictions scholars. Study of these cases, however, reveals important differences among subgroups of wrongful convictions. Whereas eyewitness misidentification, faulty forensic evidence, jailhouse informants, and false confessions have been identified as the main contributing factors leading to many wrongful convictions, the Rampart and Tulia exonerees were wrongfully convicted almost exclusively as a result of police perjury. In addition, unlike other exonerated persons, actually innocent individuals charged as a result of police wrongdoing in Rampart or Tulia only rarely contested their guilt at trial. As is the case in the justice system generally, the great majority pleaded guilty. Accordingly, these cases stand in sharp contrast to the conventional wrongful conviction story. Study of these groups of wrongful convictions sheds new light on the mechanisms that lead to the conviction of actually innocent individuals. I. INTRODUCTION Police misconduct causes wrongful convictions. Although that fact has long been known, little else occupies this corner of the wrongful convictions universe. When is police misconduct most likely to result in wrongful convictions? How do victims of police misconduct respond to false allegations of wrongdoing or to police lies about the circumstances surrounding an arrest or seizure? How often do victims of police misconduct contest false charges at trial? How often do they resolve charges through plea bargaining? While definitive answers to these questions must await further research, this study seeks to begin the Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Honorable Paul Reiber, Chief Justice, Vermont Supreme Court From

115 STATE STREET, PHONE: (802) 828-2228 MONTPELIER, VT 05633-5201 FAX: (802) 828-2424 STATE OF VERMONT SENATE CHAMBER MEMORANDUM To: Honorable Paul Reiber, Chief Justice, Vermont Supreme Court From: Senator c 'ard Sears, Chair, Senate Committee on Judiciary Senator el, Chair, Senate Committee on Appropriations Date: February 015 Subject: Judiciary Budget We recognize that the Judiciary, like the Legislature, is a separate branch of government and has an extremely difficult job balancing fiscal resources against its mission that has as its key elements: the provision of equal access to justice, protection of individual rights, and the resolution of legal disputes fairly and in a timely manner. We commend the Judiciary for its willingness to work with us to address the fiscal challenges that we have faced over the years. As you know we again face a serious fiscal challenge in the upcoming FY 2016 budget. With the revenue downgrade we are facing a total shortfall for FY 2016 of $112 million in the General Fund. This represents an 8% shortfall from the resources needed to fund current services. The Governor's fiscal year 2016 budget includes a savings target of $500,000 for Judicial operations. The budget also envisioned potential reductions in FY 2016 pay act funding and other personnel savings which could create additional pressures on the Judiciary budget and the criminal justice system generally. The Governor further proposed language in the Budget Adjustment bill for a plan to produce such savings to be submitted by prior to March 31, 2015. As was the case in the House, we have chosen not to include any specific language in the Budget Adjustment bill regarding FY 2016 reduction. -

Supreme Court of Louisiana

Supreme Court of Louisiana FOR IMMEDIATE NEWS RELEASE NEWS RELEASE #050 FROM: CLERK OF SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA The Opinions handed down on the 18th day of October, 2017, are as follows: BY GUIDRY, J.: 2017-CC-0482 PHILIP SHELTON v. NANCY PAVON (Parish of Orleans) After reviewing the applicable law, we hold that La. Code Civ. Pro. art. 971(F)(1)(a), which states that “[a]ny written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial body” is an “[a]ct in furtherance of a person’s right of petition or free speech … in connection with a public issue,” must nonetheless satisfy the requirement of La. Code Civ. Pro. art. 971(A)(1), that such statements be made “in connection with a public issue….” We therefore conclude the court of appeal was correct in reversing the trial court’s ruling granting Dr. Shelton’s special motion to strike, and in awarding reasonable attorney fees and costs to Ms. Pavon as the prevailing party, to be determined by the trial court on remand. Accordingly, the judgment of the court of appeal is affirmed. AFFIRMED WEIMER, J., dissents and assigns reasons. CLARK, J., dissents for the reasons given by Justice Weimer. HUGHES, J., dissents with reasons. CRICHTON, J., additionally concurs and assigns reasons. 10/18/17 SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA No. 2017-CC-0482 PHILIP SHELTON VERSUS NANCY PAVON ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEAL, FOURTH CIRCUIT, PARISH OF ORLEANS GUIDRY, Justice We granted the writ application to determine whether the court of appeal erred in reversing the trial court’s ruling granting the plaintiff’s special motion to strike defendant’s reconventional demand for defamation, pursuant to La. -

Download Alex S. Vitale

The End of Policing The End of Policing Alex S. Vitale First published by Verso 2017 © Alex S. Vitale 2017 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-289-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-291-7 (US EBK) ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-290-0 (UK EBK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Vitale, Alex S., author. Title: The end of policing / Alex Vitale. Description: Brooklyn : Verso, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2017020713 | ISBN 9781784782894 (hardback) | ISBN 9781784782917 (US ebk) | ISBN 9781784782900 (UK ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Police—United States. | Police misconduct—United States. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Freedom & Security / Law Enforcement. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Discrimination & Race Relations. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Public Policy / General. Classification: LCC HV8139 .V58 2017 | DDC 363.20973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020713 Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Contents 1. The Limits of Police Reform 2. The Police Are Not Here to Protect You 3. The School-to-Prison Pipeline 4. “We Called for Help, and They Killed My Son” 5. Criminalizing Homelessness 6. The Failures of Policing Sex Work 7. The War on Drugs 8. Gang Suppression 9. -

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures The Vermont Public Interest Action Project Office of Career Services Vermont Law School Copyright © 2021 Vermont Law School Acknowledgement The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures represents the contributions of several individuals and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their ideas and energy. We would like to acknowledge and thank the state court administrators, clerks, and other personnel for continuing to provide the information necessary to compile this volume. Likewise, the assistance of career services offices in several jurisdictions is also very much appreciated. Lastly, thank you to Elijah Gleason in our office for gathering and updating the information in this year’s Guide. Quite simply, the 2021-2022 Guide exists because of their efforts, and we are very appreciative of their work on this project. We have made every effort to verify the information that is contained herein, but judges and courts can, and do, alter application deadlines and materials. As a result, if you have any questions about the information listed, please confirm it directly with the individual court involved. It is likely that additional changes will occur in the coming months, which we will monitor and update in the Guide accordingly. We believe The 2021-2022 Guide represents a necessary tool for both career services professionals and law students considering judicial clerkships. We hope that it will prove useful and encourage other efforts to share information of use to all of us in the law school career services community. -

In the Supreme Court of Iowa

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 18–1050 Filed June 14, 2019 ALEX WAYNE WESTRA, Appellant, vs. IOWA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, Appellee. Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Polk County, Arthur E. Gamble, Judge. A motorist appeals a district court ruling denying his petition for judicial review of an agency decision suspending his driver’s license for one year. AFFIRMED. Matthew T. Lindholm of Gourley, Rehkemper, & Lindholm, P.L.C., West Des Moines, for appellant. Thomas J. Miller, Attorney General, and Robin G. Formaker, Assistant Attorney General, for appellee. 2 MANSFIELD, Justice. This case began when a driver tried to reverse course. But it presents the question whether our court should reverse course. Specifically, should we overrule precedent and apply the exclusionary rule to driver’s license revocation proceedings when an Iowa statute dictates otherwise? In Westendorf v. Iowa Department of Transportation, 400 N.W.2d 553, 557 (Iowa 1987), superseded by statute as recognized by Brownsberger v. Department of Transportation, 460 N.W.2d 449, 450–51 (Iowa 1990), we declined to apply the exclusionary rule so long as the enumerated statutory conditions for license revocation were met. Later, the general assembly enacted a limited exception to Westendorf. See Iowa Code § 321J.13(6) (2017). This requires the Iowa Department of Transportation (DOT) to rescind revocation of a driver’s license if there has been a criminal prosecution for operating while intoxicated (OWI) and the criminal case determined that the peace officer did not have reasonable grounds to believe a violation of the OWI laws had occurred or that the chemical test was otherwise inadmissible or invalid. -

The Rampart Scandal

Human Rights Alert, NGO PO Box 526, La Verne, CA 91750 Fax: 323.488.9697; Email: [email protected] Blog: http://human-rights-alert.blogspot.com/ Scribd: http://www.scribd.com/Human_Rights_Alert 10-04-08 DRAFT 2010 UPR: Human Rights Alert (Ngo) - The United States Human Rights Record – Allegations, Conclusions, Recommendations. Executive Summary1 1. Allegations Judges in the United States are prone to racketeering from the bench, with full patronizing by US Department of Justice and FBI. The most notorious displays of such racketeering today are in: a) Deprivation of Liberty - of various groups of FIPs (Falsely Imprisoned Persons), and b) Deprivation of the Right for Property - collusion of the courts with large financial institutions in perpetrating fraud in the courts on homeowners. Consequently, whole regions of the US, and Los Angeles is provided as an example, are managed as if they were extra-constitutional zones, where none of the Human, Constitutional, and Civil Rights are applicable. Fraudulent computers systems, which were installed at the state and US courts in the past couple of decades are key enabling tools for racketeering by the judges. Through such systems they issue orders and judgments that they themselves never consider honest, valid, and effectual, but which are publicly displayed as such. Such systems were installed in violation of the Rule Making Enabling Act. Additionally, denial of Access to Court Records - to inspect and to copy – a First Amendment and a Human Right - is integral to the alleged racketeering at the courts - through concealing from the public court records in such fraudulent computer systems. -

Hello and Thank You for Your Interest. I Want to Provide You with Information

Hello and thank you for your interest. I want to provide you with information about my legal background. I have been practicing law in state and federal trial and appellate courts since 1988. Although my interests and experience run a wide range, my primary areas of focus center around civil rights work, employment and labor issues, and protecting the rights of individuals whose rights have even violated by others, typically governmental actors and large private employers. I have extensive trial experience in these types of cases, and I invite you to look up the numerous reported cases that I have handled. A sample of several of the cases I have handled is attached, and these cases involve various civil, employment and commercial matters, including constitutional rights, discrimination, employment law and sundry types of commercial disputes, such as antitrust, securities, and contract cases. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact me. Thank you. 14-CV-8065 (VEC) UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK Airday v. City of New York 406 F. Supp. 3d 313 (S.D.N.Y. 2019) Decided Sep 13, 2019 14-CV-8065 (VEC) 09-13-2019 George AIRDAY, Plaintiff, v. The CITY OF NEW YORK and Keith Schwam, Defendants. Nathaniel B. Smith, Law Office of Nathaniel B. Smith, New York, NY, for Plaintiff. Christopher Aaron Seacord, Jeremy Laurence Jorgensen, William Andrew Grey, Paul Frederick Marks, Don Hanh Nguyen, New York City Law Depart. Office of the Corporation Counsel, New York, NY, Garrett Scott Kamen, Fisher & Phillips LLP, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, for Defendants. -

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York Office of the President PRESIDENT Bettina B. Plevan (212) 382-6700 Fax: (212) 768-8116 [email protected] www.abcny.org January 25, 2005 Dear Sir/Madam: Please find attached commentary on the Inquiries Bill, currently before the House of Lords. The Association of the Bar of the City of New York (the “Association”) is an independent non- governmental organization of more than 23,000 lawyers, judges, law professors, and government officials. Founded in 1870, the Association has a long history of dedication to human rights, notably through its Committee on International Human Rights, which investigates and reports on human rights conditions around the world. Among many other topics, the Committee has recently published reports on national security legislation in Hong Kong and human rights standards applicable to the United States’ interrogation of detainees. The Committee has been monitoring adherence to human rights standards in Northern Ireland for the past 18 years. During this time, the Committee has sponsored three missions to Northern Ireland, covering reform of the criminal justice system, use of emergency laws, and the status of investigations into past crimes, including in particular the murders of solicitors Rosemary Nelson and Patrick Finucane. The Committee’s interest in the Inquiry Bill stems from our belief that it could have devastating consequences for the Finucane inquiry, as well as other inquiries into human rights cases from Northern Ireland. Beyond these cases, we believe the Bill, if passed into law, would concentrate power in the executive in a problematic way and jeopardize the integrity of investigations into matters of public concern. -

10307 <888> 09/30/13 Monday 11:40 P.M. I Drank a 24 Ounce Glass of 50% Schweppes Ginger Ale and 50% Punch

10307 <888> 09/30/13 Monday 11:40 P.M. I drank a 24 ounce glass of 50% Schweppes Ginger Ale and 50% punch. http://www.stamfordvolvo.com/index.htm . When I was driving my 1976 Volvo 240 many years ago, I chatted with a Swedish girl down on the pier on Steamboat Road who apparently was http://www.kungahuset.se/royalcourt/royalfamily/hrhcrownprincessvictoria.4.39616051158 4257f218000503.html . She was attending www.yale.edu at the time and living in Old Greenwich. http://www.gltrust.org/ Greenwich Land Trust http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24328773 Finnish Saunas !!!!!! Mystery 13th Century eruption traced to Lombok, Indonesia 'TomTato' tomato and potato plant unveiled in UK CIO <888> 09/30/13 Monday 10:10 P.M. In watching "Last Tango in Halifax" this past Sunday evening, they talked about having eight foot snow drifts in Halifax, England, so I guess they have bad weather there in the winter. On October 1, as usual or today, a lot of the seasonal workers around here will be heading south for the winter to join the the larger number of winter residents down south. The weather is still nice here, but there is a bit of a chill in the air. There will probably still be a few hardy individuals left up north to face the oncoming winter. I have friends in Manhattan that live near the Winter Palace http://www.metmuseum.org/ . CIO <888> 09/30/13 Monday 9:45 P.M. My order for 50 regular $59 Executive 3-Button Camel Hair Blazer- Sizes 44-52 for $62.53 with tax and shipping will not be available until November 1, 2013, since it is back ordered. -

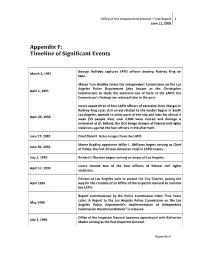

Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events

Office of the Independent Monitor: Final Report 1 June 11, 2009 Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events George Holliday captures LAPD officers beating Rodney King on March 2, 1991 tape. Mayor Tom Bradley forms the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department (also known as the Christopher April 1, 1991 Commission) to study the excessive use of force in the LAPD; the Commission’s findings are released later in the year. Jurors acquit three of four LAPD officers of excessive force charges in Rodney King case; civil unrest related to the verdict begins in South Los Angeles, spreads to other parts of the city and lasts for almost a April 29, 1992 week (55 people died, over 2,000 were injured and damage is estimated at $1 billion); the DOJ brings charges of federal civil rights violations against the four officers in the aftermath. June 27, 1992 Chief Daryl F. Gates resigns from the LAPD. Mayor Bradley appointee Willie L. Williams begins serving as Chief June 30, 1992 of Police, the first African‐American chief in LAPD history. July 1, 1993 Richard J. Riordan begins serving as mayor of Los Angeles. Jurors convict two of the four officers of federal civil rights April 17, 1993 violations. Citizens of Los Angeles vote to amend the City Charter, paving the April 1995 way for the creation of an Office of the Inspector General to monitor the LAPD. Report commissioned by the Police Commission titled “Five Years Later: A Report to the Los Angeles Police Commission on the Los May 1996 Angeles Police Department’s Implementation of Independent Commission Recommendations” is released.