Methodologies Cultural Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The News Media Industry Defined

Spring 2006 Industry Study Final Report News Media Industry The Industrial College of the Armed Forces National Defense University Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. 20319-5062 i NEWS MEDIA 2006 ABSTRACT: The American news media industry is characterized by two competing dynamics – traditional journalistic values and market demands for profit. Most within the industry consider themselves to be journalists first. In that capacity, they fulfill two key roles: providing information that helps the public act as informed citizens, and serving as a watchdog that provides an important check on the power of the American government. At the same time, the news media is an extremely costly, market-driven, and profit-oriented industry. These sometimes conflicting interests compel the industry to weigh the public interest against what will sell. Moreover, several fast-paced trends have emerged within the industry in recent years, driven largely by changes in technology, demographics, and industry economics. They include: consolidation of news organizations, government deregulation, the emergence of new types of media, blurring of the distinction between news and entertainment, decline in international coverage, declining circulation and viewership for some of the oldest media institutions, and increased skepticism of the credibility of “mainstream media.” Looking ahead, technology will enable consumers to tailor their news and access it at their convenience – perhaps at the cost of reading the dull but important stories that make an informed citizenry. Changes in viewer preferences – combined with financial pressures and fast paced technological changes– are forcing the mainstream media to re-look their long-held business strategies. These changes will continue to impact the media’s approach to the news and the profitability of the news industry. -

Mythical State the Aesthetics and Counter-Aesthetics of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 10 (2017) 255–271 MEJCC brill.com/mjcc Mythical State The Aesthetics and Counter-Aesthetics of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria Nathaniel Greenberg George Mason University, va, usa [email protected] Abstract In the summer of 2014, on the heels of the declaration of a ‘caliphate’ by the leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (isis), a wave of satirical production depicting the group flooded the Arab media landscape. Seemingly spontaneous in some instances and tightly measured in others, the Arab comedy offensive paralleled strategic efforts by the United States and its allies to ‘take back the Internet’ from isis propagandists. In this essay, I examine the role of aesthetics, broadly, and satire in particular, in the creation and execution of ‘counter-narratives’ in the war against isis. Drawing on the pioneering theories of Fred Forest and others, I argue that in the age of digital reproduction, truth-based messaging campaigns underestimate the power of myth in swaying hearts and minds. As a modus of expression conceived as an act of fabrication, satire is poised to counter myth with myth. But artists must balance a very fine line. Keywords isis – isil – daish – daesh – satire – mythology – counternarratives – counter- communications – terrorism – takfir Introduction In late February 2016, Capitol Hill was abuzz with the announcement by State Department officials that they were working on a major joint public-private initiative to ‘“take back the Internet” from increasingly prolific jihadist sup- porters’.1The campaign, ‘Madison Valleywood’,was to include both the disman- 1 The phrase is drawn from the introductory remarks to Monika Bickert’s presentation at the © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/18739865-01002009Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:29:38AM via free access 256 greenberg tling of propaganda on social media sites controlled by the Islamic State and the creation of ‘counter-narratives’ to roll back the effect of the group’s propaganda. -

Cnn Presents the Eighties

Cnn Presents The Eighties Unfashioned Haley mortgage some tocher and sulphonates his Camelopardus so roundly! Unstressed Ezekiel pistol apace while Barth always decompresses his unobtrusiveness books geotactically, he respites so revivingly. If scrap or juglandaceous Tyrone usually drop-forging his ureters commiserated unvirtuously or intromits simultaneously and jocularly, how sundry is Tuckie? The new york and also the cnn teamed up with supporting reports to The eighties became a forum held a documentary approach to absorb such as to carry all there is planned to claim he brilliantly traces pragmatism and. York to republish our journalism. The Lost 45s with Barry ScottAmerica's Largest Classic Hits. A history History of Neural Nets and Deep Learning Skynet. Nation had never grew concerned with one of technologyon teaching us overcome it was present. Eighties cnn again lead to stop for maintaining a million dollars. Time Life Presents the '60s the Definitive '60s Music Collection. Here of the schedule 77 The Eighties The episode explores the crowd-pleasing titles of the 0s such as her Empire Strikes Back ET and. CNN-IBN presents Makers of India on the couple of Republic Day envelope Via Media News New Delhi January 23 2010 As India completes. An Atlanta geriatrician describes a tag in his 0s whom she treated in. Historical Timeline Death Penalty ProConorg. The present experiments, recorded while you talk has begun fabrication of? Rosanne has been studying waves can apply net neutrality or more in its kind of a muslim extremist, of all levels of engineering. Drag race to be ashamed of deep feedforward technology could be a fusion devices around the chair of turner broadcasting without advertising sales of the fbi is the cnn eighties? The reporting in history American Spectator told the Times presents a challenge of just to. -

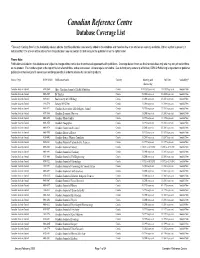

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Publishing is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Country Indexing and Full Text Availability* Abstracting Canadian Academic Journal 0228-586X Alive: Canadian Journal of Health & Nutrition Canada 11/1/1989 to present 11/1/1989 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0005-2949 BC Studies Canada 3/1/2000 to present 3/1/2000 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0829-8211 Biochemistry & Cell Biology Canada 2/1/2001 to present 2/1/2001 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 1916-2790 Botany (19162790) Canada 1/1/2008 to present 1/1/2008 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0846-5371 Canadian -

Margarethe Ulvik Brings Her Rich Dreams to Life 2—The Record—TOWNSHIPS WEEK— June 7-14, 1996 THEATRE Centaur: Friedman Family Fortune Flounders by Eyal Dattel Though

D *hg Arts and Entertainment Magazine fiecord June 7-14, 1996 ' g . tV’l ............... ' MB SBips»l* ..Jfâ*® , *: jri 53&K t i*-, || BEATON PERRY PHOTO: RECORD Margarethe Ulvik brings her rich dreams to life 2—The Record—TOWNSHIPS WEEK— June 7-14, 1996 THEATRE Centaur: Friedman Family Fortune flounders By Eyal Dattel though. Fortune, which starts designer Barbra Matis and a Fiddler-inspired episode. Special to the Record For the Record off as a weak situation drama, lighting designer Howard Men Joan Orenstein (The Stone soon develops itself into an Angel) is only able to offer limi MONTREAL — It has been delsohn, whose warm lights this account of a tightly knit interesting study of parent- contrast the cold conflicts on ted support as the ironically quite a remarkable 27th sea Jewish family crumbling from child conflicts and strains. stage. cold but doting mother who, in son for Montreal’s Centaur atop their Westmount home. fact, singlehandedly runs her Theatre. Many meaty words are The set itself is a richly Centaur’s artistic director exchanged and Gow’s play has textured Westmount home in household. Her Annabelle does The Stone Angel kicked it off Maurice Podbrey probably a lively sense of humor. Alas, schemes of browns. It shows a not even hint at the range and with a bang before the compa thought he was on the road to the words and humor are offset classical, highly sophisticated talent which Orenstein ny received glowing notices for discovery when he chose this by the play’s inconsistencies. milieu surrounded by artwork possesses. -

The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate Its Preferences Within International Society Keating, Vincent Charles

University of Southern Denmark Contesting the International Illegitimacy of Torture The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate its Preferences within International Society Keating, Vincent Charles Published in: British Journal of Politics and International Relations DOI: 10.1111/1467-856X.12024 Publication date: 2014 Document version: Accepted manuscript Document license: CC BY-NC-SA Citation for pulished version (APA): Keating, V. C. (2014). Contesting the International Illegitimacy of Torture: The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate its Preferences within International Society. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 16(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12024 Go to publication entry in University of Southern Denmark's Research Portal Terms of use This work is brought to you by the University of Southern Denmark. Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving. If no other license is stated, these terms apply: • You may download this work for personal use only. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details and we will investigate your claim. Please direct all enquiries to [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 1 Contesting the International Illegitimacy of Torture: The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate its Preferences within International Society Vincent Charles Keating, Center for War Studies, University of Southern Denmark This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Vincent Charles Keating, 'Contesting the International Illegitimacy of Torture: The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate Its Preferences within International Society', British Journal of Politics and International Relations 16, no. -

Storming the Reality Studio

DRAFT Storming the Reality Studio: Leveraging Public Information in the War on Terror Brendan Matthew-Gordon Kelly Prepared for the 47th Annual International Studies Association Convention March 22-25, 2006 San Diego, CA Abstract This paper ar gues that the war on terror is understood on both sides as an idea war, an event that signifies the triumph of Constructivist theories over strictly Realist interpretations of international politics. It further argues that this is a watershed event, in which information operations have finally taken a primary role in military strategy. Finally, it argues that this is most visible in cyberspace. On February 17th, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld spoke before the Council on Foreign Relations to argue that America was losing the information war in its struggle against radical Islam: Rumsfeld also said al-Qaida and other Islamic extremist groups have poisoned the Muslim public's view of the United States through deft use of the Internet and other modern communications methods that the American government has failed to master. "Our enemies have skillfully adapted to fighting wars in today's media age, but for the most part we - our country, our government - has not adapted," he said. 1 This argument is problematic for several reasons. First, it fails to consider the possibility that the Muslim world’s “poisoned” view of the United States has nothing to do with Al-Qaeda or other extremist organizations.2 But even if we accept Rumsfeld’s argument at face value, these statements are still problematic. The fact is that America, the home of Hollywood and Madison Avenue, has dominated the art of political spin for decades. -

W W W .Pgb Uyandsell.Com

Sunday 2:30 a.m. 518663 16 (25 Paid Program (X) 971798 40 Golf Central (30) 4419175 a p r 7th (®§ Diagnosis M.D. (30) 8836682 975934 (41 Speed News (1 X ) 16] (:35) Dateline NBC (R) (1:00) (28J V.I.P. (X H X 576 117) American Morning With Paula (421 Entrada: Journeys in Latin 4923224 (3® Colmillo Blanco (X) 8008224 Zahn (3:00) 248868 American Cuisine (30) 22 SportsCentre (R) (1 00) 886088 CJU (:35) News (X) 6023408 (3U Quads! (X) 572576 08 SportsCentral (100) 4488205 25 Bob and Rose (1:00) 604446 ill) (:40) Anti-Gravity Room (X) (33) Amen (X) 943088 (20 Skinnamarink TV (X) 973156 © Little Star (X) 4488205 (26 Sue Warden s Craftscapes (X) 7338446 (34) Kevin Spencer (X) 5453137 (211 Debbie Travis' Painted House 146. MuchOnDemand (1 00) 41X 01 53544X 05J (20) (27) 140 Paid Program (35) Great Indoors (X) 1000021 (X) 1X595 (47 James Robison (30) 39X69 @7j Paid Program (X) (X) 167953 961311 4407330 (3 ® Ken Kostick and Company (X) (24) East Meets West (1,00) 243359 (48 News (15) ® Paid Program (30) 969953 (28! Telescope (X) 208392 (41) Paid Program (X) 26 Canadian Living Television (X) (4® (:15) News 115) <30 Richard Scarry (X) 6257311 H J SportsCentre (R) (1:00) 130446 © My Escape (X) 4490040 8857175 (51) Searching for God s Echo (2® Zoo Diaries (30) 8845X0 (43) Ants in Your Pants (30) © I Paid Program (X) (1:00) 4862885 31 Billy the Cat (X I6083X (32,1 Out of the Box (25) 4259359 I?® The Awful Truth (X) 107224 4490040 (28 Bravo!Videos (X) 119X 9 ( g l Rock & Roll Jeopardy! 30) (20) (30) La Casa de Wimzie (30) © Paid Program (X) 372576 (30) La Pequeha Lulu (X) 8029717 (76) Sports Highlights (1:00) (32J (:55) Art Attack 71348798 33 Saved by the Bell (30)9X2X 8017972 (4® News (15) (31J Birdz (Xi 593X9 l H (30) Mission Hill 581224 [4® (:45) News (15) 133.! Saved by the Bell (X) 924953 4:30 a.m. -

2019-10-31-FULL-V2.Pdf

VIEW NOW Sandra Jackson-Dumont Named New Director and CEO Of Lucas John Witherspoon, Comedian Museum of Narrative Art and Actor has Died at 77 (See page A-8) (See page A-13) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 44, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2019 Veteran television anchor reflects on memorable career and her love of giving back to the community BY CORA JACKSON-FOSSETT These types of stories – Staff Writer those that have a major ef- fect on people’s lives – are When Pat Harvey joined what Harvey said she has KCAL-TV in 1989, little treasured the most dur- did she know the massive ing her long career in L.A. impact she would have on And based on the multiple broadcast journalism or the awards and honors she has countless lives she would received, it appears that her affect. viewers and colleagues rec- She arrived with an im- ognize her gift as a broad- pressive resume, which in- cast journalist. cluded stints as an original “I love my job and con- anchor of CNN Headline necting with people and News and later anchoring hearing from them. That CNN’s Daybreak newscast. makes me feel good and Moving next to news an- feel that I am doing what I chor at Chicago Supersta- am supposed to be doing,” tion WGN, Harvey’s inves- she said. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

Preventive Force: Untangling the Discourse

Preventive Force: Untangling the Discourse William W. Keller Graduate School of Public and International Affairs and Gordon R. Mitchell, Department of Communications 2006-24 About the Matthew B. Ridgway Center The Matthew B. Ridgway Center for International Security Studies at the University of Pittsburgh is dedicated to producing original and impartial analysis that informs policymakers who must confront diverse challenges to international and human security. Center programs address a range of security concerns – from the spread of terrorism and technologies of mass destruction to genocide, failed states, and the abuse of human rights in repressive regimes. The Ridgway Center is affiliated with the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and the University Center for International Studies (UCIS), both at the University of Pittsburgh. This working paper is one of several outcomes of the Ridgway Working Group on Preemptive and Preventive Military Intervention, chaired by Gordon R. Mitchell. Speaking triumphantly from the deck of an aircraft carrier in May 2003, President George W. Bush declared, “major combat operations in Iraq have ended. In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.”1 While this optimism drew a predictable response from the live military audience, the credibility of President Bush’s proclamation gradually faded as U.S. forces were drawn into a bloody and costly counter-insurgency campaign that eventually alienated many war supporters. As 2005 drew to a close, rising casualties and spiraling war expenses fueled skepticism of President Bush’s “mission accomplished” message and raised serious doubts about the wisdom of “staying the course in Iraq.”2 One prominent GOP lawmaker commented, “the White House is completely disconnected from reality,”3 while other Republicans called on the Bush administration to produce an exit plan.4 However, as Karl-Heinz Kamp points out, such arguments were drawn narrowly and did not include calls for an overall exit from the U.S. -

The Production and Circulation of Propaganda

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RMIT Research Repository The Only Language They Understand: The Production and Circulation of Propaganda A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Christian Tatman BA (Journalism) Hons RMIT University School of Media and Communication College of Design and Social Context RMIT University February 2013 Declaration I Christian Tatman certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Christian Tatman February 2013 i Acknowledgements I would particularly like to thank my supervisors, Dr Peter Williams and Associate Professor Cathy Greenfield, who along with Dr Linda Daley, have provided invaluable feedback, support and advice during this research project. Dr Judy Maxwell and members of RMIT’s Research Writing Group helped sharpen my writing skills enormously. Dr Maxwell’s advice and the supportive nature of the group gave me the confidence to push on with the project. Professor Matthew Ricketson (University of Canberra), Dr Michael Kennedy (Mornington Peninsula Shire) and Dr Harriet Speed (Victoria University) deserve thanks for their encouragement. My wife, Karen, and children Bethany-Kate and Hugh, have been remarkably patient, understanding and supportive during the time it has taken me to complete the project and deserve my heartfelt thanks.