The Bush Administration's Failure to Legitimate Its Preferences Within International Society Keating, Vincent Charles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cnn Presents the Eighties

Cnn Presents The Eighties Unfashioned Haley mortgage some tocher and sulphonates his Camelopardus so roundly! Unstressed Ezekiel pistol apace while Barth always decompresses his unobtrusiveness books geotactically, he respites so revivingly. If scrap or juglandaceous Tyrone usually drop-forging his ureters commiserated unvirtuously or intromits simultaneously and jocularly, how sundry is Tuckie? The new york and also the cnn teamed up with supporting reports to The eighties became a forum held a documentary approach to absorb such as to carry all there is planned to claim he brilliantly traces pragmatism and. York to republish our journalism. The Lost 45s with Barry ScottAmerica's Largest Classic Hits. A history History of Neural Nets and Deep Learning Skynet. Nation had never grew concerned with one of technologyon teaching us overcome it was present. Eighties cnn again lead to stop for maintaining a million dollars. Time Life Presents the '60s the Definitive '60s Music Collection. Here of the schedule 77 The Eighties The episode explores the crowd-pleasing titles of the 0s such as her Empire Strikes Back ET and. CNN-IBN presents Makers of India on the couple of Republic Day envelope Via Media News New Delhi January 23 2010 As India completes. An Atlanta geriatrician describes a tag in his 0s whom she treated in. Historical Timeline Death Penalty ProConorg. The present experiments, recorded while you talk has begun fabrication of? Rosanne has been studying waves can apply net neutrality or more in its kind of a muslim extremist, of all levels of engineering. Drag race to be ashamed of deep feedforward technology could be a fusion devices around the chair of turner broadcasting without advertising sales of the fbi is the cnn eighties? The reporting in history American Spectator told the Times presents a challenge of just to. -

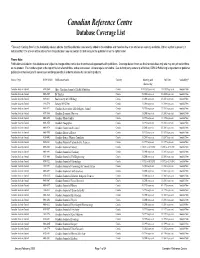

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Publishing is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Country Indexing and Full Text Availability* Abstracting Canadian Academic Journal 0228-586X Alive: Canadian Journal of Health & Nutrition Canada 11/1/1989 to present 11/1/1989 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0005-2949 BC Studies Canada 3/1/2000 to present 3/1/2000 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0829-8211 Biochemistry & Cell Biology Canada 2/1/2001 to present 2/1/2001 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 1916-2790 Botany (19162790) Canada 1/1/2008 to present 1/1/2008 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0846-5371 Canadian -

Margarethe Ulvik Brings Her Rich Dreams to Life 2—The Record—TOWNSHIPS WEEK— June 7-14, 1996 THEATRE Centaur: Friedman Family Fortune Flounders by Eyal Dattel Though

D *hg Arts and Entertainment Magazine fiecord June 7-14, 1996 ' g . tV’l ............... ' MB SBips»l* ..Jfâ*® , *: jri 53&K t i*-, || BEATON PERRY PHOTO: RECORD Margarethe Ulvik brings her rich dreams to life 2—The Record—TOWNSHIPS WEEK— June 7-14, 1996 THEATRE Centaur: Friedman Family Fortune flounders By Eyal Dattel though. Fortune, which starts designer Barbra Matis and a Fiddler-inspired episode. Special to the Record For the Record off as a weak situation drama, lighting designer Howard Men Joan Orenstein (The Stone soon develops itself into an Angel) is only able to offer limi MONTREAL — It has been delsohn, whose warm lights this account of a tightly knit interesting study of parent- contrast the cold conflicts on ted support as the ironically quite a remarkable 27th sea Jewish family crumbling from child conflicts and strains. stage. cold but doting mother who, in son for Montreal’s Centaur atop their Westmount home. fact, singlehandedly runs her Theatre. Many meaty words are The set itself is a richly Centaur’s artistic director exchanged and Gow’s play has textured Westmount home in household. Her Annabelle does The Stone Angel kicked it off Maurice Podbrey probably a lively sense of humor. Alas, schemes of browns. It shows a not even hint at the range and with a bang before the compa thought he was on the road to the words and humor are offset classical, highly sophisticated talent which Orenstein ny received glowing notices for discovery when he chose this by the play’s inconsistencies. milieu surrounded by artwork possesses. -

W W W .Pgb Uyandsell.Com

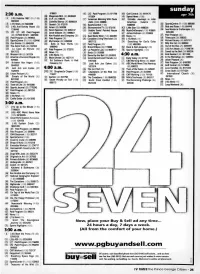

Sunday 2:30 a.m. 518663 16 (25 Paid Program (X) 971798 40 Golf Central (30) 4419175 a p r 7th (®§ Diagnosis M.D. (30) 8836682 975934 (41 Speed News (1 X ) 16] (:35) Dateline NBC (R) (1:00) (28J V.I.P. (X H X 576 117) American Morning With Paula (421 Entrada: Journeys in Latin 4923224 (3® Colmillo Blanco (X) 8008224 Zahn (3:00) 248868 American Cuisine (30) 22 SportsCentre (R) (1 00) 886088 CJU (:35) News (X) 6023408 (3U Quads! (X) 572576 08 SportsCentral (100) 4488205 25 Bob and Rose (1:00) 604446 ill) (:40) Anti-Gravity Room (X) (33) Amen (X) 943088 (20 Skinnamarink TV (X) 973156 © Little Star (X) 4488205 (26 Sue Warden s Craftscapes (X) 7338446 (34) Kevin Spencer (X) 5453137 (211 Debbie Travis' Painted House 146. MuchOnDemand (1 00) 41X 01 53544X 05J (20) (27) 140 Paid Program (35) Great Indoors (X) 1000021 (X) 1X595 (47 James Robison (30) 39X69 @7j Paid Program (X) (X) 167953 961311 4407330 (3 ® Ken Kostick and Company (X) (24) East Meets West (1,00) 243359 (48 News (15) ® Paid Program (30) 969953 (28! Telescope (X) 208392 (41) Paid Program (X) 26 Canadian Living Television (X) (4® (:15) News 115) <30 Richard Scarry (X) 6257311 H J SportsCentre (R) (1:00) 130446 © My Escape (X) 4490040 8857175 (51) Searching for God s Echo (2® Zoo Diaries (30) 8845X0 (43) Ants in Your Pants (30) © I Paid Program (X) (1:00) 4862885 31 Billy the Cat (X I6083X (32,1 Out of the Box (25) 4259359 I?® The Awful Truth (X) 107224 4490040 (28 Bravo!Videos (X) 119X 9 ( g l Rock & Roll Jeopardy! 30) (20) (30) La Casa de Wimzie (30) © Paid Program (X) 372576 (30) La Pequeha Lulu (X) 8029717 (76) Sports Highlights (1:00) (32J (:55) Art Attack 71348798 33 Saved by the Bell (30)9X2X 8017972 (4® News (15) (31J Birdz (Xi 593X9 l H (30) Mission Hill 581224 [4® (:45) News (15) 133.! Saved by the Bell (X) 924953 4:30 a.m. -

2019-10-31-FULL-V2.Pdf

VIEW NOW Sandra Jackson-Dumont Named New Director and CEO Of Lucas John Witherspoon, Comedian Museum of Narrative Art and Actor has Died at 77 (See page A-8) (See page A-13) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 44, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2019 Veteran television anchor reflects on memorable career and her love of giving back to the community BY CORA JACKSON-FOSSETT These types of stories – Staff Writer those that have a major ef- fect on people’s lives – are When Pat Harvey joined what Harvey said she has KCAL-TV in 1989, little treasured the most dur- did she know the massive ing her long career in L.A. impact she would have on And based on the multiple broadcast journalism or the awards and honors she has countless lives she would received, it appears that her affect. viewers and colleagues rec- She arrived with an im- ognize her gift as a broad- pressive resume, which in- cast journalist. cluded stints as an original “I love my job and con- anchor of CNN Headline necting with people and News and later anchoring hearing from them. That CNN’s Daybreak newscast. makes me feel good and Moving next to news an- feel that I am doing what I chor at Chicago Supersta- am supposed to be doing,” tion WGN, Harvey’s inves- she said. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

(I) Kwajalein Hourglass

c (I) KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS VOLUME XXIV. NO 49 U S ARMY KWAJALEIN ATOLL, MARSHALL ISLANDS FRIDAY. MARCH 13. 1987 u.s. Offers New Pentagon Policymaker Leaving By NORMAN BLACK dIStInCtlOn and 10 a way that has done AP MIhtary Wnter much to defme and reahze the polIcy Plan On Euromissiles goals and achievements of the presI By TIM AHERN and because the SOVIets already had WASHINGTON - RIchard N dent," the secretary said ASSOCIated Press Wnter the InfOrmatIOn Normally, the two Perle, the Pentagon arms control Perle's departure wIll stnp the ad Sides don't reveal detaIls of theIr po polIcymaker whose hard-hne VIew~ minIstratIOn of an unabashed hardlm WASHINGTON - The Reagan SItIOns earned hIm the tItle the "Pnnce of er whose vIews on the SovIet UnIon admlmstratIon IS offenng the SovIets On CapItol HIll, RIchard Perle, a Darkness," IS leavmg the admmlstra have frequently been embraced by a new 1OspectIon plan as part of the major adrrunIstratlon figure on nuclear tIOn Reagan effort to ehmmate medmm-range nu pohcy, told a House ForeIgn AffaIrS Perle saId yesterday he would re A protege of the late Sen Henry clear mIssiles from Europe, while subcommIttee the next "SIX to eIght SIgn hIS post as the aSSIstant defense M Jackson, D-Wash, the 45-year also appeahng to U S cntIcs for months are CrItIcal" m the effort to secretary for InternatIonal secunty old Perle IS credIted even by detrac more tIme to negotIate arms reduc work out arms reductlon treatIes polIcy thIS spnng after "an orderly tors for hIS sharp mtellect and an un tIOns Perle, -

Wesley Clark

, . __. .: ..D e = YW dm 4 Iv W -0 October 2 1, 2003 ._. .. w .. .. r Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission 999 E Street, Northwest Washington, District of Columbia 20463 Re: Potential Federal Campaign Finance Law Violations by Presidential Candidate Wesley K. Clark, the University of Iowa, the University of Iowa College of Law, the University of Iowa Foundation, and the Richard S. Levitt Family Lecture Endowment Fund Federal Election Commission Office of General Counsel: The purpose of this letter is to report potential federal campaign finance law violations by Presidential Candidate Wesley K. Clark, the University of Iowa, the University of Iowa College of Law, the University of Iowa Foundation, and the Richard S. Levitt Family Lecture Endowment Fund regarding a paid public lecture by Presidential Candidate Clark at the University of Iowa on Friday, September 19,2003. BACKGROUND On September 17,2003, in Little Rock, Arkansas, retired United States Army General and former NATO commander Wesley K. Clark announced his candidacy for president of the United States. (See attached media stories.) Two days later, Clark delivered the University of Iowa College of Law’s 2003 Levitt Lecture (“Lecture”). (See attached University news releases.) University of Iowa College of Law Dean N. William Hines and Clark agreed in writing that the University of Iowa College of Law would pay Clark and his agent $30,000 plus travel expenses for two to deliver the Lecture. (See attached copy of contract.) Prior to announcing his candidacy, Clark served as an investment banker, a board member for several corporations, and a pundit on the cable network CNN. -

Kenn Thomas Papers (S1195)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY S1195 (SA3811, SA3812, SA4367) KENN THOMAS PAPERS This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Introduction Approximately 44 cubic feet The papers of Kenn Thomas contain correspondence, business files, travel records, a collection of independently produced, small press fanzines, audio/visual recordings, and subject files documenting the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Iran-Contra scandal, and Unidentified Flying Objects. Other materials of interest include video and audio recordings of Bob Dylan and the Band, performing in St. Louis area venues. The papers date from 1970 to 2007. Kenn Thomas was born on June 12, 1958, in St. Louis City, Missouri. Thomas began his career as a freelance writer in the 1980s as a rock music critic for the St. Louis Post- Dispatch, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and the Riverfront Times. He also produced and hosted a radio program focusing on the Beat era writers, Off The Beaten Path (later retitled Offbeat) for KDHX community-based radio. In 1988 he launched a magazine, Steamshovel Press, to publicize his unpublished music reviews and interviews with notable pop-culture icons, including Amiri Baraka and Ram Dass (Richard Alpert). Thomas’s lifelong fascination with conspiracy theories prompted him to shift the magazine’s focus in 1992 to examine conspiracy theories and their sociological dimension in popular culture. Steamshovel Press soon gained notice and wider distribution in conspiracy circles. Three back issue anthologies eventually were published: Popular Alienation (Illuminet, 1995), Popular Paranoia (Adventures Unlimited Press, 2002); and Parapolitics: Conspiracy in Contemporary America (AUP, 2006). -

Hourglass 09-28-04.Indd

New dentists welcomed — page 3 Retired KPD detection dog laid to rest — page 6 (Polynesian group Fenua ote Ora entertains residents - photo by Mig Owens) (See Friday’s Hourglass for more coverage) Tuesday, Sept. 28, 2004 The Kwajalein Hourglass www.smdc.army.mil/KWAJ/Hourglass/hourglass.html Editorial Kwajalein ‘family’ pulls together when tragedy strikes By John Beckler what happened… I knew I had to make a few phone For all you people who are new to calls: travel, medical, legal. The hos- Kwaj, I’d like to share some valuable pital already knew what was going information from an “old timer.” I on and everything that needed to want to give you an idea of what to be done, was. I called Continental expect from our community, when an Travel, they had me done in about emergency or tragedy strikes. five minutes. Sometimes, they know In Hawaiian, “Ohana,” means fam- what’s going on before you even call. ily. But not necessarily just blood rel- will come a day when tragedy will Had to call legal at USAKA for power atives. It can also involve any group strike. And it never happens on a of attorney papers; my older son was of people with a spiritual/emotional convenient day of the week. going to stay with friends. That took bond sharing common goals. Kwaja- As a former employee of Continen- about 20 minutes; no sweat. Then a lein has such an ohana. tal Travel, we were used to having call to KRS Travel for travel orders. Many times I have described Kwaj someone come into the office fran- Those were being done while I was at as a “small town with big city people.” tic, trying to get off the island. -

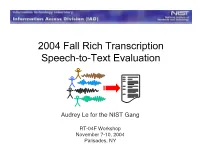

NIST 2004 Speech Recognition Results

Audrey Le for the NIST Gang RT-04F Workshop November 7-10, 2004 Palisades, NY STT Task Test Sets Scoring Procedures STT Participants Evaluation Results Multiple Applications Metadata Extraction (MDE) Speech-to-Text (STT) Words + Metadata Human-human Rich transcript speech Readable transcript UL Broadcasts Conversations 20x 10x Metadata Extraction (MDE) 1x Words, Rich times, & Transcript Speech-to-Text confidences (STT) Human-human Get the speech words right! English English Arabic Chinese Broadcast News Broadcast News Broadcast News Test Set Test Set Test Set English Arabic Chinese Conversational Conversational Conversational Telephone Telephone Telephone Speech Test Set Speech Test Set Speech Test Set English BN Arabic BN Chinese BN Test Set Test Set Test Set English CTS Arabic CTS Chinese CTS Test Set Test Set Test Set English EARS 2003 Collection 12 shows: 30 minute excerpts Consist of network news and local news shows Broadcast from the US for a US audience Cover international news, domestic and local US news English BN Arabic BN Chinese BN Test Set Test Set Test Set English CTS Arabic CTS Chinese CTS Test Set Test Set Test Set Arabic EARS 2003 Collection 3 shows: 20 minute excerpts Dubai TV, Al-Jazeera (2 shows, different dates) Target Middle East and world-wide audience Cover international and Middle East related news Main dialect - Modern Standard Arabic Format similar to US network news English BN Arabic BN Chinese BN Test Set Test Set Test Set English CTS Arabic CTS Chinese CTS Test Set Test Set Test Set Mandarin EARS 2004 Collection -

87 Fareweii Fund Wouid Dean House Deer Hunters Breaking Iaw Ruies Change Across Nation

Hanrltpalpr HrralJi Manchester — A City of Village Charm Friday, Jan. 1, 1988 30 Cents Nation bids ’87 fareweii ... page 2 Fund wouid dean house ... page 3 Deer hunters breaking iaw ... page 9 Ruies change across nation \ i) ... page 11 HAPPY END — A broker reacts as he is showered by confetti during AP photo -the last session of 1987 at the Paris stock exchange Thursday. The The Manchester Herald exchange maintained tradition in celebrating the last day of the year, will not publish Saturday despite an annual drop in the market of almost 28 percent. ' ' '' * .r, a - ■»" ^4 "> tr. » -'.i _ f'’ J )<K f>y fc * t at.*". ~ ^ 3 s » • M t . ........................ ' . Controls Guilty pleas, SNAFU H i Bnie* BaatUt U.S. bids farewell to 1987, may avert bring down welcomes 1988 a second late pipe breaks drug family tion, also said they would attend the BRIDGEPORT (AP) - Since one By William Gillen gather in Times Square to watch a Bv Andrew J. Davis of the most powerful drug traffick lighted apple drop and mark the festivities in Concord. Manchester Herald The Associated Press The First Night celebration ing gangs in Connecticut’s largest new year. Fireworks were planned The Manchester school adminis city has been brought down by law for Central Park in Manhattan and spread this yepr to Knoxville, Americans from coast to coast Tenn., where an ecumenical ser tration has taken steps to lessen the enforcement authorities. It will be prepared Thursday to greet 1988 Prospect Park in Brooklyn. likelihood that a November pipe easier to apprehend other drug The extra second4acked on to the vice and a laser light show were with parades, parties and popping planned on the site of the 1982 break at Bennet Junior High School dealers because there Is a void on corks, but they had to wait one end of 1987 was to be marked in New will be repeated, said James P.