An Historically-Informed Approach to the Conservation of Vernacular Architecture: the Case of the Phlegrean Farmhouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia

Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Assessorato allo Sviluppo Dipartimento Lavoro e Impresa Servizio Impresa e Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive BANDO RETI Legge 266/97 - Annualità 2011 Agevolazioni a favore delle piccole imprese e microimprese operanti nei quartieri: Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia, Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno, Ponticelli, Barra, San Giovanni a Teduccio, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Stella, San Carlo Arena, Mercato, Pendino, Avvocata, Montecalvario, S.Giuseppe, Porto. Art. 14 della legge 7 agosto 1997, n. 266. Decreto del ministro delle attività produttive 14 settembre 2004, n. 267. Pagina 1 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 SOMMARIO ART. 1 – OBIETTIVI, AMBITO DI APPLICAZIONE E DOTAZIONE FINANZIARIA ART. 2 – REQUISITI DI ACCESSO. ART. 3 – INTERVENTI IMPRENDITORIALI AMMISSIBILI. ART. 4 – TIPOLOGIA E MISURA DEL FINANZIAMENTO ART. 5 – SPESE AMMISSIBILI ART. 6 – VARIAZIONI ALLE SPESE DI PROGETTO ART. 7 – PRESENTAZIONE DOMANDA DI AMMISSIONE ALLE AGEVOLAZIONI ART. 8 – PROCEDURE DI VALUTAZIONE E SELEZIONE ART. 9 – ATTO DI ADESIONE E OBBLIGO ART. 10 – REALIZZAZIONE DELL’INVESTIMENTO ART. 11 – EROGAZIONE DEL CONTRIBUTO ART. 12 –ISPEZIONI, CONTROLLI, ESCLUSIONIE REVOCHE DEI CONTRIBUTI ART. 13 – PROCEDIMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO ART. 14 – TUTELA DELLA PRIVACY ART. 15 – DISPOSIZIONI FINALI Pagina 2 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Art. 1 – Obiettivi, -

Elenco Sezioni Elettorali

' A e T I n L o i A z P I QUARTIERE e Denominazione Plesso Ubicazione Plesso C I S N ° U N M 1 CHIAIA 37 4° CIRCOLO DIDATTICO "M. Cristina di Savoia" VIALE M. CRISTINA DI SAVOIA 1 CHIAIA 40 4° CIRCOLO DIDATTICO "M. Cristina di Savoia" VIALE M. CRISTINA DI SAVOIA 1 CHIAIA 41 4° CIRCOLO DIDATTICO "M. Cristina di Savoia" VIALE M. CRISTINA DI SAVOIA 1 CHIAIA 33 IST. PROFESSIONALE "Bernini" VIA ARCO MIRELLI,19/A 1 CHIAIA 48 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Baracca" plesso "D'Annunzio" PIAZZA S.MARIA DEGLI ANGELI A PIZZOFALCONE,8 1 CHIAIA 45 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Baracca" plesso "V. Emanuele" VICO S.MARIA APPARENTE,12/A 1 CHIAIA 46 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Baracca" plesso "V. Emanuele" VICO S.MARIA APPARENTE,12/A 1 CHIAIA 47 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Baracca" plesso "V. Emanuele" VICO S.MARIA APPARENTE,12/A 1 CHIAIA 49 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Baracca" plesso "V. Emanuele" VICO S.MARIA APPARENTE,12/A 1 CHIAIA 36 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "G. Fiorelli" VIA TOMMASO CAMPANELLA,1/A 1 CHIAIA 19 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Nevio" VIA TORRE CERVATI,9 1 CHIAIA 54 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO "Nevio" VIA TORRE CERVATI,9 1 CHIAIA 18 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 32 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 38 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 42 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 44 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 53 LICEO "Mercalli" VIA ANDREA D'ISERNIA,34 1 CHIAIA 20 LICEO "Umberto I" PIAZZA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA,6 1 CHIAIA 22 LICEO "Umberto I" PIAZZA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA,6 1 CHIAIA 23 LICEO "Umberto I" PIAZZA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA,6 1 CHIAIA 27 LICEO "Umberto I" PIAZZA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA,6 1 CHIAIA 50 LICEO "Umberto I" PIAZZA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA,6 DIPARTIMENTO SEGRETERIA GENERALE - Servizio Anagrafe - Stato civile - Elettorale 1 Ufficio Sedi Elettorali tel. -

Metropolitane E Linee Regionali: Mappa Della

Formia Caserta Caserta Benevento Villa Literno San Marcellino Sant’Antimo Frattamaggiore Cancello Albanova Frignano Aversa Sant’Arpino Grumo Nevano 12 Acerra 11Aversa Centro Acerra Alfa Lancia 2 Aversa Ippodromo Giugliano Alfa Lancia 4 Casalnuovo igna Baiano Casoria 2 Melito 1 in costruzione Mugnano Afragola La P Talona e e co o linea 1 in costruzione Casalnuovo ont Ar erna iemont Piscinola ola P Brusciano Salice asalcist Scampia co P Prat C De Ruggier Chiaiano Par 1 11 Aeroporto Pomigliano d’ Giugliano Frullone Capodichino Volla Qualiano Colli Aminei Botteghelle Policlinico Poggioreale Materdei Madonnelle Rione Alto Centro Argine Direzionale Palasport Montedonzelli Salvator Stazione Rosa Cavour Centrale Medaglie d’Oro Villa Visconti Museo 1 Garibaldi Gianturco anni rocchia Quar v cio T esuvio Montesanto a V Quar La Piazza Olivella S.Gioeduc fficina cola to C Socca Corso Duomo T O onticelli onticelli De Meis er ollena O Quar P T T Quattro in costruzione a Barr P P C P Guindazzi fficina entr P ianura rencia raiano P C Vittorio Dante to isani ia Giornate Morghen Emanuele t v v o o o e Montesanto S.Maria Bartolo Longo Madonna dell’Arco Via del Pozzo 5 8 C Gianturco S.Giorgio Grotta Vanvitelli Fuga A Toledo S. Anastasia Università Porta 3 a Cremano del Sole Petraio Corso Vittorio Nolana S. Giorgio Cavalli di Bronzo Villa Augustea ostruzione Cimarosa Emanuele 3 12131415 Portici Bellavista Somma Vesuviana Licola B Palazzolo linea 7 in c Augusteo Municipio Immacolatella Portici Via Libertà Quarto Corso Vittorio Emanuele A Porto di Napoli Rione Trieste Ercolano Scavi Marina di Marano Corso Vittorio Ottaviano di Licola Emanuele Parco S.Giovanni Barra 2 Ercolano Miglio d’Oro Fuorigrotta Margherita ostruzione S. -

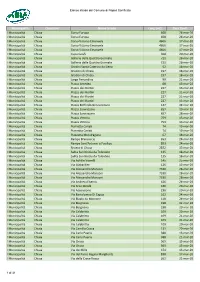

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità -

Portale Monotematico Sulle Cavità Di Pianura

Assessorato Governo del Territorio Regione Campania Assessorato Governo del Territorio SUN Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli Facoltà di Architettura “Luigi Vanvitelli” DCP Dipartimento di Cultura del Progetto BENECON Centro Regionale di Competenza per i Beni Culturali Ecologia Economia A.T.S. Facoltà Architettura (mandataria) A&C 2000 srl (mandante) SOGESI spa (mandante) Portale monotematico sulle cavità di Pianura Realizzazione di un portale monotematico dedicato alla cavità di Pianura da inserire nel portale regionale/sportello cartografico Rappresentante Legale Prof. Arch. Carmine Gambardella Responsabile scientifico Prof. Ing. Giancarlo Atza Coordinatore Prof. Arch. Sabina Martusciello IL TERRITORIO | IL LUOGO | LA CAVA WP1 Storia WP2 Topografia nel corso dei secoli WP3 Presentazione dinamica del rilievo 3D con il laser-scanner WP4 Vista virtuale delle cavità WP5 Evoluzione del rapporto tra la cavità WP6 Aspetti e problematiche di natura geologica WP7 Metodologie di estrazione WP8 Metodi di trasporto sui luoghi di utilizzazione dei materiali WP9 Le più importanti opere realizzate con il piperno della cava di Pianura WP1 | Storia 5 WP1 Storia Il territorio di Pianura tra Neapoli e Puteoli Lungo il versante occidentale della collina dei Camaldoli, ad una quota di circa 210 metri, nei pressi della Masseria del Monte, si apre la galleria della cava di Pianura (1). Il piperno è uno dei prodotti vulcanici caratteristici della Campania, comunemente usato nelle opere architettoniche soprattutto a partire dal XV secolo. Fino alla metà del XX secolo era opinione prevalente che il piperno fosse stato prodotto da un solo vulcano dei Campi Flegrei, il cosiddetto vulcano di Soccavo, ubicato al bordo della caldera Archiflegrea, ai piedi della collina dei Camaldoli. -

Soccavo Pianura Il Programma Locale Degli Interventi E Dei Servizi Sociali

IX M U N I C I P A L I T À Soccavo Pianura Il Programma Locale degli interventi e dei servizi sociali 9^ M U N I C I P A L I T A‘ SOCCAVO PIANURA 1 INDICE ANALITICO 1) Analisi del Territorio ……………………………………………pag 8 2) Contesto socio-demografico 2.1 Dati demografici :aspetti generali………………………………………pag 10 2.2 Area Minori 2.2.1 Aspetti generali……………………………………………………………………………pag 13 2.2.2 La dispersione scolastica…………………………………………………………….pag 15 2.2.3 Le famiglie tra funzioni educative e compiti di cura………………….pag 17 2.2.4 Servizi sociali territoriali:area minori……………………………………….. pag 18 2.3 Area Anziani 2.3.1 Aspetti generali…………………………………………………………………………….pag 21 2.3.2 Servizi sociali territoriali: area anziani………………………………………..pag 22 2.4 Area Disabili 2.4.1 Aspetti generali…………………………………………………………………………….pag 23 2.4.2 Servizi sociali territoriali: Area Disabili……………………………………… pag 24 2.5 I fenomeni di esclusione sociale 2.5.1 Area occupazionale………………………………………………………………………pag 26 2.5.2 Area Immigrati (Questione Rom)......................................... pag 27 2.5.3 Area Farmacodipendenze e Salute Mentale……………………………… pag 29 2 3) Analisi delle risorse sociali 3.1 Strutture pubbliche di aggregazione ……………………………………….pag 32 3.2 Servizio politiche per i minori, l’infanzia e l’adolescenza ……….pag 32 3.3 Servizio politiche per gli anziani e i disabili ……………………………..pag 34 3.4 Area socio-sanitaria ……………………………………………………………………………pag 35 3.4.1 Farmacodipendenze e salute mentale ………………………………………………………pag 35 4) Priorità, obiettivi, azioni …………………………………………………pag 36 4.1 Area Famiglia e minori …………………………………………………………………..pag 36 4.2 Area anziani e disabili …………………………………………………………………..pag 38 4.3 Area Immigrati e Contrasto alla Povertà …………………………………..pag 39 3 IL PROGRAMMA LOCALE DEGLI INTERVENTI E DEI SERVIZI SOCIALI Profilo di Comunità La prima parte del documento conterrà il profilo del territorio e le esigenze della popolazione. -

Riferimenti Degli Enti Cui Sono Affidate Le Attivita' E Dei Csst

AZIONI DI SOSTEGNO EDUCATIVO E PERCORSI FORMATIVI TEORICI/PRATICI RIVOLTE AD ADOLESCENTI – DOTE COMUNE A seguito di apposito Avviso pubblico emanato con Determinazione Dirigenziale n. 24 del 15/06/16 per l’affidamento delle attività denominate "Azioni di sostegno educativo e percorsi formativi teorici/pratici rivolti ad adolescenti – Dote comune", con Disposizione Dirigenziale n. 55 del 05/12/16 sono state affidate le attività agli Enti di seguito indicati in tabella per la durata di 12 mesi aumentata fino ad un massimo di 16 mesi. ENTE MUNICIPALITA’ CSST ISTITUTO SALESIANO ERNESTO MENECHINI 3 - 5 Stella, Vomero, Arenella Miano, San Pietro a Patierno, Secondigliano, COOPERATIVA SOCIALE L'UOMO E IL LEGNO 7 - 8 Piscinola,Chiaiano, Scampia COOPERATIVA SOCIALE L'ORSA MAGGIORE 9 - 10 Soccavo, Pianura, Fuorigrotta, Bagnoli RIFERIMENTI DEGLI ENTI CUI SONO AFFIDATE LE ATTIVITA’ E DEI CSST RIFERI- ENTE COORDINATORE E-MAIL ENTE TEL. ENTE PEC ENTE CSST MAIL CSST MENTO GESTORE TERRITO RIALE MUNICIPALITA’ ISTITUTO MARIO DEL PIANO donvannisdb@ 0817511340 Istitutoe.menichini@pe Stella [email protected] 3 – 5 SALESIANO libero.it c.it li.it ERNESTO MENECHINI Vomero [email protected] Arenella [email protected] MUNICIPALITA’ COOPERATI PIRAS STEFANIA info@luomoeil 0815435924 coopluomoeillegno@leg Miano [email protected] 7 – 8 VA SOCIALE legno.com almail.it L'UOMO E San Pietro [email protected] IL LEGNO apoli.it Secondiglia [email protected]. no it Piscinola [email protected] Chiaiano [email protected] Scampia [email protected] MUNICIPALITA’ COOPERATI FRANCESCA francesca.don 0817281705 [email protected] Soccavo [email protected] 9 – 10 VA SOCIALE D’ONOFRIO ofrio2@gmail. -

Programma Di Risanamento Ambientale E Rigenerazione Urbana

PROGRAMMA DI RISANAMENTO AMBIENTALE E DI RIGENERAZIONE URBANA SITO DI RILEVANTE INTERESSE NAZIONALE DI BAGNOLI- COROGLIO Agenzia nazionale per l'attrazione degli investimenti e lo sviluppo d'impresa S.p.A. - Via Calabria, 46 00187 Roma Sommario 1 INTRODUZIONE .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Il quadro normativo di riferimento del SIN di Bagnoli Coroglio: evoluzione nel tempo ed assetto attuale della legislazione ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 I compiti del soggetto attuatore ........................................................................................................ 9 2 LA STRUTTURA DEL PROGRAMMA .......................................................................................................... 11 2.1 Il percorso ed il metodo seguito nella definizione del Programma ................................................ 11 2.2 L’attività svolta nel corso di questi mesi ......................................................................................... 12 2.3 La programmazione delle attività da svolgere nella fase successiva .............................................. 15 2.4 Inquadramento dell’area ................................................................................................................. 16 2.4.1 Inquadramento Catastale ....................................................................................................... -

1 1 QS Appendice Statistica

Progetto Nuval “Azioni di sostegno alle attività del Sistema Nazionale di Valutazione e dei Nuclei di Valutazione” Progetto Pilota di Valutazione Locale Caso Studio I QUARTIERI SPAGNOLI DI NAPOLI Appendice 1 Analisi statistica: il contesto socio-economico e demografico dei QS Appendice statistica Sommario A.2 Identificazione delle aree e trattamento dei dati...................................................................9 A.3 Il Censimento del 1991 ................................................................................................... 10 A.4 Il Censimento del 2001 ................................................................................................... 22 A.5 Il Censimento del 2011 ................................................................................................... 32 A.6 Le quotazioni immobiliari comparate dell’area dei QS.......................................................... 35 A.7 Le attività economiche all’interno dei QS ........................................................................... 41 A.8 L’analisi dei dati sulle scuole ............................................................................................ 46 2 Appendice statistica A.1 Limiti municipali e sezioni di censimento Il territorio napoletano secondo i dati del Sistan 1 risulta diviso in 30 quartieri e in 10 municipa- lità. La Fig. A.1.1 illustra l’area napoletana suddivisa per quartieri mentre la Fig. A.1.2 descrive l’area napoletana suddivisa per municipalità. Ciascuna municipalità può inglobare uno o più quartieri. -

Strutture Accreditate

Strutture Accreditate aggiornamento: mag 2016 Descrizione tipo Quartiere Codice Denominazione Indirizzo CAP E-mail Sito web Telefono Numero Tipo struttura assistenza erogata struttur struttura fax a ASSISTENZA AGLI ANZIANI Arenella RSA301 Casa Di Cura Padre Viale Dei Pini, 53 80131 rsa.padreannibale@ 081 7416516 081 19318082 STRUTTURA (zona rione Annibale di Francia gmail .com RESIDENZIALE Alto) srl San Lorenzo RSA300 ISTITUTO POVERE VIALE COLLI AMINEI 80139 AMMINISTRAZIONE RSASANGIUSEPPE@I 081 5921858 081 5921858 STRUTTURA FIGLIEDELLA N. 24 @ISTITUTOSUOREVI STITUTOSUOREVISIT RESIDENZIALE VISITAZIONE - RSA SITAZIONE AZIONE.IT S. GIUSEPPE ASSISTENZA AI DISABILI FISICI Arenella RSA301 Casa Di Cura Padre Viale Dei Pini, 53 80131 rsa.padreannibale@ 081 7416516 081 19318082 STRUTTURA (zona rione Annibale di Francia gmail .com RESIDENZIALE Alto) srl ASSISTENZA AIDS Ponticelli 522407 IL MILLEPIEDI V.BOTTEGHELLE,139 80147 MILLEPIEDI94@INWI 081 7590916 081 5442078 STRUTTURA SOCIETA' -MASSERIA RAUCCI ND.IT RESIDENZIALE COOPERATIVA SOCIALE ONLUS ASSISTENZA IDROTERMALE Rione 150246 TERME DI AGNANO VIA AGNANO 80125 081 6189111 081 5701756 ALTRO TIPO DI Flegreo S.p.A. ASTRONI, 24 STRUTTURA TERRITORIALE ASSISTENZA PER TOSSICODIPENDENTI Stella 491233 CENTRO LA TENDA VIA SANITA', 95/96 80136 [email protected] 081 5444638 STRUTTURA onlus SEMIRESIDENZIA LE Pagina 1 di 35 Descrizione tipo Quartiere Codice Denominazione Indirizzo CAP E-mail Sito web Telefono Numero Tipo struttura assistenza erogata struttur struttura fax a ATTIVITA` CLINICA Arenella 470174 KREBS VICO ACITILLO, 80128 [email protected] 081 5601680 081 5601680 AMBULATORIO LABORATORIO DI 55/57 E RICERCHE CLINICHE LABORATORIO S.R.L. Arenella 470129 CARDIONOVA s.a.s. VIA E. SUAREZ, 38 80100 [email protected] 081 5562733 081 5562733 AMBULATORIO t E LABORATORIO Arenella 470120 CUTIS s.as. -

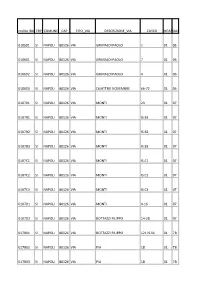

Codice IBU ERP COMUNE CAP TIPO VIA DESCRIZIONE VIA CIVICO COMPARTOSTRALCIO

codice IBU ERP COMUNE CAP TIPO_VIA DESCRIZIONE_VIA CIVICO COMPARTOSTRALCIO 010501 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA GRIMALDI PAOLO 1 01 05 010601 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA GRIMALDI PAOLO 7 01 06 010602 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA GRIMALDI PAOLO 4 01 06 010603 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA QUATTRO NOVEMBRE 66-72 01 06 010701 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI 23 01 07 0107B1 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.B1 01 07 0107B2 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.B2 01 07 0107B3 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.B3 01 07 0107C1 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.C1 01 07 0107C2 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.C2 01 07 0107C3 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI IS.C3 01 07 0107D1 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA MONTI 4-16 01 07 0107D2 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA BOTTAZZI FILIPPO 14-28 01 07 017B01 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA BOTTAZZI FILIPPO 121 IS.01 01 7B 017B02 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA PIA 18 01 7B 017B03 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA PIA 18 01 7B 017B04 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA BOTTAZZI FILIPPO 107-113 01 7B 017B05 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA PIA IS.05 01 7B 017S0T NO NAPOLI 80147 VIA VELOTTI EGIDIO 18 01R203 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE CROCE DI PIPERNO PEGASO 01 R2 01R204 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO ANTARES 01 R2 01R205 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO ALPHA 01 R2 01R206 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO CENTAURO 01 R2 01R207 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO ERCOLE 01 R2 01R208 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO RIGEL 01 R2 01R209 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO ROSS 01 R2 01R210 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO WOLF 01 R2 01R211 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA ENEIDE ORIONE 01 R2 01R2E1 SI NAPOLI 80126 VIA VICINALE PALAZZIELLO -

INFORMASALUTE Accesso Al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale Per I Cittadini Non Comunitari

Progetto cofinanziato da ISTITUTO NAZIONALE UNIONE SALUTE, MIGRAZIONI MINISTERO MINISTERO EUROPEA E POVERTÀ DELLA SALUTE DELL’INTERNO Fondo Europeo per l'Integrazione dei cittadini di Paesi terzi INFORMASALUTE Accesso al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale per i cittadini non comunitari I Servizi Sanitari di NAPOLI e Provincia INFORMASALUTE Accesso al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale per i cittadini non comunitari I PRINCIPALI SERVIZI SANITARI DI NAPOLI E PROVINCIA I PRINCIPALI SERVIZI SANITARI DI NAPOLI E PROVINCIA I PRINCIPALI SERVIZI SANITARI DI NAPOLI E PROVINCIA Il territorio provinciale di Napoli è diviso in tre ASL (Aziende Sa- nitarie Locali) ognuna delle quali ha una sede principale e una serie di distretti socio-sanitari diffusi in modo da facilitare l’ac- cesso dei cittadini: • ASL Napoli 1 - Centro articolata in 11 distretti (da 24 a 34) • ASL Napoli 2 - Nord articolata in 13 distretti (da 35 a 47) • ASL Napoli 3 - Sud articolata in 12 distretti (da 48 a 59) 2 • TERRITORI DI RIFERIMENTO E UFFICI RELAZIONI CON IL PUBBLICO (URP) ASL NAPOLI 1 - CENTRO Via Comunale del Principe 13/a URP: 081.2544487 DISTRETTO 24 Chiaia, Posillipo, Isola di Capri, S. Ferdinando Via Croce Rossa 9 - Tel. 081.2547432/475/341 DISTRETTO 25 Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta Via Winspeare 67 - Tel. 081.2548165 DISTRETTO 26 Pianura, Soccavo Soccavo: Via C. Scherillo 12 - Tel. 081.2548390 TERRITORI DI RIFERIMENTO E UFFICI RELAZIONI CON IL PUBBLICO (URP) DISTRETTO 27 Arenella, Vomero Via S. Gennaro ad Antignano 42 - Tel. 081.2549752/3 DISTRETTO 28 Chiaiano, Piscinola, Marianella, Scampia Viale della Resistenza 25 - Tel. 081.2546518 DISTRETTO 29 Colli Aminei, Stella, S.