Facing Assad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Dayton S. Mak

Library of Congress Interview with Dayton S. Mak The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project DAYTON S. MAK Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: August 9, 1989 Copyright 2010 ADST Q: Dayton, when and where were you born? MAK: I was born in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, July 10, 1917. Q: Let's talk about the family, let's go on the Mak side. What do you know about them? MAK: The Mak original name was three-barrel Mak van Waay, which in Dutch would be Mak fon vei [pronounces in Dutch]. They were from Dordrecht, the Netherlands. The family had an antique showroom there, an auction house a bit like Sotheby's. Q: ...in... MAK: In Dordrecht. That was the Mak van Waay family. They then moved to Amsterdam. At the same time, anther part of the family, a son, I believe, wanted to establish a Mak van Waay firm in Dordrecht itself. According to Dutch law, they couldn't do that. There could only be one firm Mak van Waay, so they opened the Firma Mak in Dordrecht. The Firma Mak still exists, and the big building remains on the tour of the old city of Dordrecht. The Mak van Waay part, of which I'm a member, stayed in Amsterdam until about 15 years ago, when the last Mak van Waay died. He had no children. So, the Mak van Waay in Interview with Dayton S. Mak http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000739 Library of Congress Holland effectively died out. -

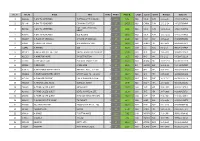

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

After the Accords Anwar Sadat

WMHSMUN XXXIV After the Accords: Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet Background Guide “Unprecedented committees. Unparalleled debate. Unmatched fun.” Letters From the Directors Dear Delegates, Welcome to WMHSMUN XXXIV! My name is Hank Hermens and I am excited to be the in-room Director for Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet. I’m a junior at the College double majoring in International Relations and History. I have done model UN since my sophomore year of high school, and since then I have become increasingly involved. I compete as part of W&M’s travel team, staff our conferences, and have served as the Director of Media for our college level conference, &MUN. Right now, I’m a member of our Conference Team, planning travel and training delegates. Outside of MUN, I play trumpet in the Wind Ensemble, do research with AidData and for a professor, looking at the influence of Islamic institutions on electoral outcomes in Tunisia. In my admittedly limited free time, I enjoy reading, running, and hanging out with my friends around campus. As members of Anwar Sadat’s cabinet, you’ll have to deal with the fallout of Egypt’s recent peace with Israel, in Egypt, the greater Middle East and North Africa, and the world. You’ll also meet economic challenges, rising national political tensions, and more. Some of the problems you come up against will be easily solved, with only short-term solutions necessary. Others will require complex, long term solutions, or risk the possibility of further crises arising. No matter what, we will favor creative, outside-the-box ideas as well as collaboration and diplomacy. -

NCV Issue 7 2018.Indd

Locally Owned and Operated Est. 2000 FREE! Vol. 18 - Issue 7 • July 11, 2018 - August 8, 2018 INSIDE: Winery Guide Vintage Ohio August, 3rd & 4th Great Lakes Medieval Faire! July 14 – Aug. 19th Painesville Party in the Park, July 13th – 15th Interviews - Colin Dussault, Marion Ross & Allen Ravenstine The Amphicar Celina Swim-In Entertainment, Dining & Leisure Connection Read online at www.northcoastvoice.com North Coast Voice OLD FIREHOUSE 5499 Lake RoadWINERY East • Geneva-on-the Lake, Ohio Restaurant & Tasting Room Live Entertainment 7 Days! (See inside back cover for listings) Hours: Sun- urs Noon to 7pm, Entertainment Fri & Sat Noon to 11pm Tasting Rooms 1-800-Uncork-1 all weekend. (see ad on pg. 5) FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND Kitchen Open! EVENTS, SEE OUR AD ON PG. 7 Summer Hours: Mon. - Closed Hours: Mon 12-4 wine sales Tue., Wed. & ur. Noon – 7 Tues. Closed Fri. & Sat. Noon - 11 HUNDLEY Wed 12-7 • Thurs 12-8 • Fri 12 - 9 Sun. Noon - 7 CELLARS Sat 12-10 • Sun 12-5 834 South County Line Road 6451 N. RIVER RD., HARPERSIELD, OHIO 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfi eld, Oh Harpersfi eld, Ohio 44041 WED. 12 - 7, THURS. 12-8 216.973.2711 SAT. 12- 9, SUN. 12-6 440.415.0661 www.laurellovineyards.com www.bennyvinourbanwinery.com WWW.HUNDLEY CELLARS.COM [email protected] [email protected] If you’re in the mood for a palate pleasing wine tasting accompanied by a delectable entree from our restaurant, Ferrante Winery and Ristorante is the place for you! Summer Hours Tasting Room: Mon. - Tues. 10-5 pm One of the newest Wed & Thurs. -

Big Country Rarities Free Downloads Sound & Vision Thing

big country rarities free downloads Sound & Vision Thing. Out of print, underrated, forgotten music, movies, etc. Check comments for links. full discography, rar, etc. Thursday, December 13, 2018. Big Country. Big Country never got the recognition they deserved in the US but still remained a big band in the UK and Europe until the end of their career in the late '90s. Their first 2 albums were produced by Steve Lillywhite, who also worked with U2 and Simple Minds. Thus, they got lumped in with those two bands, as well as The Alarm, as a new wave of anthemic rock of Gaelic origins. They were actually the most seasoned and musically proficient band of that group, right out of the gate as heard on their debut, "The Crossing." They went on to make great albums (except No Place Like Home) for the rest of their career until lead singer Stuart Adamson's tragic suicide in 2000. 3 comments: As an American fan of Big Country, I would disagree that they *never* got the recognition they deserved here. "In A Big Country" was frequently played on the radio and MTV, and I saw them headline at The Fox, one of Atlanta's premier venues, during their first US tour. Enthusiasm didn't carry over to the albums that followed, and in that sense they deserved better in this country. 1983 - The Crossing [Deluxe Edition] 1984 - Steeltown [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1986 - The Seer [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1988 - Peace in Our Time [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1990 - Through A Big Country [Remastered 1996] 1991 - No Place Like Home 1993 - The Buffalo Skinners [Complete Sessions 2019] 1994 - Without The Aid Of A Safety Net [2019] 1995 - Why the Long Face [Deluxe Expanded 2018] 1998 - Restless Natives & rarities 1998 - The Nashville Sessions 1999 - Driving to Damascus [Bonus Tracks] 2001 - Under Cover 2005 - Rarities 2013 - The Journey (w/ Mike Peters) 2017 - Wonderland: The Essential. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

1 Appendices for Covert Regime Change

Appendices for Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War Appendix I: U.S.-backed Covert Regime Change Attempts during the Cold War………………2 Appendix II: U.S.-backed Overt Regime Change Attempts during the Cold War………………65 Appendix III: Additional alleged U.S. Covert Cases……………………………………………66 Note to readers: Appendix 1 contains at least 3 sources for each of the alleged regime change attempts conducted by the United States during the Cold War. As time permits, I have been updating the appendices with additional sources and hyperlinks to collections of operational files. Additional sources are available in the footnotes of Chapters 5-8 of the book. Feel free to contact me at [email protected] if you have any additional questions. (Last updated September 2019.) 1 Appendix I: U.S. Covert Regime Change during the Cold War Target State: Italy Dates: 1947-1968 Tactics: Covert – Election influence, psychological warfare Type of Operation: Preventive Regime Replaced: Yes Examples of Primary Sources: • Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, September 15, 1951, “Analysis of the Power of the Communist Parties of France and Italy and of Measures to Counter Them,” CIA-FOIA, Doc. CIA-RDP80R01731R003200020013-5. • National Security Council, “National Security Council Report: Position of the United States with Respect to Italy in Light of the Possible Communist Participation in Government by Legal Means,” CIA-FOIA, Doc. CIA-RDP78-01617A003100010001-5 • Central Intelligence Agency, February 1948, “The Current Situation in Italy,” CIA-FOIA, Doc. 0000008669 • National Security Council, March 8, 1948, “National Security Council Report: Position of the United States with Respect to Italy in Light of the Possible Communist Participation in Government by Legal Means,” CIA-FOIA, Doc. -

Iranian Espionage in the United States and the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1979)

The Shah’s “Fatherly Eye” Iranian Espionage in the United States and the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1979) Eitan Meisels Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University 13 April 2020 Thesis Instructor: Elisheva Carlebach Second Reader: Paul Chamberlin Meisels 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Historiography, Sources, and Methods ......................................................................................... 12 Chapter 1: Roots of the Anti-SAVAK Campaign ......................................................................... 14 Domestic Unrest in Iran ............................................................................................................ 14 What Did SAVAK Aim to Accomplish? .................................................................................. 19 Chapter 2: The First Phase of the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1974) .................................... 21 Federal Suspicions Stir ............................................................................................................. 21 Counterintelligence to Campaign ............................................................................................. 24 Chapter 3: The Anti-SAVAK Campaign Expands (1975-1976) ................................................. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ARTHUR L. LOWRIE Interviewed by: Patricia Lessard and Theodore Lowrie Initial interview date: December 23, 1989 Co yright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background arly interest in Foreign Service Army service in Korean War Foreign Service exam Aleppo, Syria 1957-1959 Vice Consul ,oy Atherton as Consul -eneral Formation of .nited Arab ,epublic 0asser1s crackdo2n on communism Beirut 1931 Arabic language training Situation in 4iddle ast Khartoum 1932-1934 Political Officer Arabi7ation in the Sudan Declared P0- shortly before Abboud overthro2 Tunis 1934-1937 Political89abor Officer Ambassador ,ussell Impression of labor movement in Tunisia Assignment to Armed Forces Staff College I0,8Algerian Desk 1938-1972 Analy7ing the Sudanese guerilla force Algerian natural gas contract Dealing 2ith corporate America Baghdad 1972-1975 1 Chargé d1Affaires ,eopening the .S post in Baghdad Assessment of Belgian representation 0ationali7ation of Iraq Petroleum Company Kurdish struggle against government Improvement in ..S.-Iraqi relations Impression of Saddam Hussein Police state atmosphere in Iraq 0 A Chief of 4ission meeting Commercial relations 2ith Iraq Cairo 1975-1978 Political Counselor Sadat1s November 1977 trip to Jerusalem Briefing Israeli diplomats Impression of Sadat .nited Nations 1978-1979 4iddle ast Officer Camp David Accords Problems 2ith negotiations ..S. 4ission to uropean Communities 1979-1983 0ATO Defense College Differences bet2een urope and 4iddle ast posts PO9AD to Central Command 1983-1983 Working 2ith military Development of the ,apid Deployment Joint Task Force Difficulty gaining 4iddle ast cooperation Problem of support for Israel Conclusion -reatest achievement8disappointment ,easons for retiring INTERVIEW $: Mr. -

Interview with Frank E. Maestrone

Library of Congress Interview with Frank E. Maestrone The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR FRANK E. MAESTRONE Interviewed by: Hank Zivetz Initial interview date: June 6, 1989 Copyright 1998 ADST [Note: This interview was not edited by Ambassador Maestrone.] Q: Mr. Ambassador, just to begin, how and why did you become involved with the Foreign Service? How did you get into the diplomatic career? MAESTRONE: Well, that's a rather interesting and somewhat amusing story, in that I was a military government officer in W#rzburg, Germany right at the end of the war, and I stayed on for another year. This occurred just after the end of the war. There was an announcement that Foreign Service exams would be given again. They had been suspended during the war, and they would be given throughout the world in various places where the military people could take them. One of the testing spots was going to be Oberammergau, Germany. I had been trying to get some leave from my commanding officer, and he said, “No, we have too much to do.” Along came the circular saying you will get five days' temporary duty in Oberammergau if you want to take the Foreign Service exam. So I said, “This is a splendid idea. I'll get five days temporary duty in Oberammergau and I'll take whatever this Foreign Service exam is.” So I proceeded ahead in driving down in Interview with Frank E. Maestrone http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000737 Library of Congress my Adler convertible with my chauffeur to stay in the post hotel in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which is nearby Oberammergau and took the Foreign Service exam and I passed. -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9m52q2hk Author Wight, David M. Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERISITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by David M. Wight Dissertation Committee: Professor Emily S. Rosenberg, chair Professor Mark LeVine Associate Professor Salim Yaqub 2014 © 2014 David M. Wight DEDICATION To Michelle ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Road to the Oil Shock 14 CHAPTER 2: Structuring Petrodollar Flows 78 CHAPTER 3: Visions of Petrodollar Promise and Peril 127 CHAPTER 4: The Triangle to the Nile 189 CHAPTER 5: The Carter Administration and the Petrodollar-Arms Complex 231 CONCLUSION 277 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Sectors of the MENA as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 19 Figure 1.2 Selected Countries as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 20 Figure 1.3 Current Account Balances of the Non-Communist World, 1970-1977 22 Figure 1.4 Value of US Exports to the MENA, 1946-1977 24 Figure 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 255 iv LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Net Change in Deployment of OPEC’s Capital Surplus, 1974-1976 120 Table 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 256 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a cliché that one accumulates countless debts while writing a monograph, but in researching and writing this dissertation I have come to learn the depth of the truth of this statement.