Projects for Peace Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

Press Release

Dated : October 16, 2019 EMBASSY OF INDIA DOHA Press Release World Class Indian Artist set to thrill Doha Audience The Embassy of India, in association with the ICC Advisory Council, is organising a sitar concert on 18th Oct 2019 at 1900 PM at Katara Drama Theater, by the famous Grammy Awarded Nominee sitarist Shri Shujaat Husain Khan. The Maestro’s musical career began at the age of three when he began practicing on a specially made small sitar. By the age of six, he was recognized as a child prodigy and began giving public performances. Shujaat Khan has performed at all the prestigious music festivals in India and has performed throughout Asia, Africa, North America, and Europe. Audiences around the world are captivated by his unique style of sitar playing, his exceptional voice, and his intuitive and spontaneous approach to rhythm. “ We are glad that, as part of celebrations of India Qatar Year of Culture 2019, we are able to host an artist of his stature and talent. I am sure his performance will captivate the Doha audience, which is known to appreciate class and master artistry” said Shri P Kumaran, the Ambassador of India to Qatar. “We are happy that ICC Advisory Council could chip in with this program to support the Embassy in its effort to bring in world class Indian artists to Qatar as part of IQYOC celebrations” said KM Varghese the Chairman of the Council. ======END==== About the artist Shujaat Husain Khan is one of the greatest North Indian classical musicians of his generation. He belongs to the Imdad Khan gharana of the sitar and his style of playing sitar, known as the gayaki ang, is imitative of the subtleties of the human voice. -

Banasthali Vidyapith

BANASTHALI VIDYAPITH Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Education Curriculum Structure First Semester Examination, December, 2019 Second Semester Examination, April/May, 2020 Third Semester Examination, December, 2020 Fourth Semester Examination, April/May, 2021 Fifth Semester Examination, December, 2021 Sixth Semester Examination, April/May, 2022 Seventh Semester Examination, December, 2022 Eighth Semester Examination, April/May, 2023 BANASTHALI VIDYAPITH P.O. BANASTHALI VIDYAPITH (Rajasthan)-304022 July, 2019 15 2 No. F. 9-6/81-U.3 Government of India Ministry of Education and Culture (Department of Education) New Delhi, the 25th October, 1983 N O T I F I C A T I O N In exercise of the powers conferred by Section 3 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956 (3 of 1956) the Central Government, on the advice of the Commission, hereby declare that Banasthali Vidyapith, P. O. Banasthali Vidyapith, (Rajasthan) shall be deemed to be a University for the purpose of the aforesaid Act. Sd/- (M. R. Kolhatkar) Joint Secretary of the Government of India N O T I C E Changes in Bye-laws/Syllabi and Books may from time to time be made by amendment or remaking, and a Candidate shall, except in so far as the Vidyapith determines otherwise, comply with any change that applies to years she has not completed at the time of change. © BANASTHALI VIDYAPITH 3 Contents Page Nos. Programme Educational Objectives 4 Programme Outcomes 5 Curriculum Structure 6 Evaluation Scheme and Grading System 36 DISCIPLINARY COURSES Page Nos. 1. Applied Statistics 41 2. Computer Applications 65 3. Dramatic Art (Theatre) 88 4. -

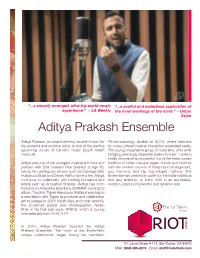

Aditya Prakash Ensemble

“...a smartly arranged, ultra-hip world music “...a soulful and melodious exploration of experience.” ~ LA Weekly the inner workings of the mind.” ~ Urban Asian Aditya Prakash Ensemble Aditya Prakash, an award-winning vocalist known for Ethnomusicology studies at UCLA, where horizons his powerful and emotive voice, is one of the leading to cross-cultural musical interaction expanded vastly. upcoming voices of Carnatic music (South Indian The young, imaginative group of musicians, who while classical). bridging seemingly disparate styles of music, create a boldly innovative and powerful mix of the deep-rooted Aditya was one of the youngest musicians to tour and tradition of Indian classical ragas, chants and rhythms perform with Sitar maestro Ravi Shankar at age 16, with the modern sounds of brass band arrangement, taking him prestigious venues such as Carnegie Hall, jazz harmony, and hip hop-infused rhythms. The Hollywood Bowl and Disney Hall to name a few. Aditya Ensemble has created an outlet for the Indian classical continues to collaborate with leading innovators and and jazz aesthetic to shine forth in an accessible, artists such as Anoushka Shankar (Aditya has been modern, playful yet powerful and dynamic way featured on Anoushka Shankar’s GRAMMY nominated album, Traveler), Tigran Hamasyan (Aditya is working on a new album with Tigran as producer and collaborator set to release in 2021) Karsh Kale and most recently, the acclaimed dancer and choreographer, Akram Khan in his final solo work, XENOS, which is touring is now internationally -

World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016

World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016 United Nations United Nations World Economic Situation and Prospects 2016 asdf United Nations New York, 2016 The report is a joint product of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Af- fairs (UN/DESA), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the five United Nations regional commissions (Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA)). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) also contributed to the report. For further information, see http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/index.shtml or contact: DESA ECLAC MR. WU HONGBO, Under-Secretary-General MS. ALICIA BÁRCENA, Executive Secretary Department of Economic and Social Affairs Economic Commission for Latin America Room S-2922 and the Caribbean United Nations Av. Dag Hammarskjöld 3477 New York, NY 10017 Vitacura USA Santiago, Chile ☎ +1-212-9635958 Chile [email protected] ☎ +56-2-22102000 [email protected] UNCTAD DR. MUKHISA KITUYI, Secretary-General ESCAP United Nations Conference on Trade DR. SHAMSHAD AKHTAR, Executive Secretary and Development Economic and Social Commission for Asia Room E-9042 and the Pacific Palais de Nations United Nations Building 1211 Geneva 10 Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Switzerland Bangkok 10200 ☎ +41-22-9175806 Thailand [email protected] ☎ +66-2-2881234 [email protected] ECA DR. CARLOS LOPES, Executive Secretary ESCWA United Nations Economic Commission for Africa MS. RIMA KHALAF, Executive Secretary Menelik II Avenue Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia P.O. -

Ustad Shujaat Khan Transcends Indian Classical Music

Ustad Shujaat Khan transcends Indian classical music Written by Anupma Khanna | Dehradun Thursday, 24 November 2011 23:47 Sporting a funky colourful watch, a vivacious ‘ultra-cool’ disposition and an attitude that reflects the fluidity of changing times; Sitar maestro Ustad Shujaat Khan transcends traditional stereotypes of Indian classical music in ways more than one. His relaxed manners, natural wise-cracks and a remarkable sense of humour are perfect compliments to a man who has suffered much in life for the cause of his independence. The seventh generation torchbearer of the embellished legacy of the Imdad gharana that has produced many a virtuoso, Shujaat has in fact cemented a distinct identity of his own. His intuitive genius and spontaneous versatility have floored music aficionados in Asia, Africa, North America and Europe. He is one of the five Indians who made it to Amazon’s 100 greatest music albums in the world in 2009 and has won honour from the United Nations, a Grammy nomination and more. However, for him, reaching the boulevard of fame had its share of toil and tears. “During my music training years, I was a completely dedicated and submitted disciple of my prodigious father. At times, after strumming the strings of the Sitar for several exhausting hours, overnight practice that would make my fingers bleed, he felt that I wasn’t good enough. When I performed, there was always the burden of matching the sky-high expectations set by my father. Treading the path carved by your forefathers is not all glitzy like it appears. The journey is beset with travail,” he told The Pioneer. -

Room for a (Long) View

A Khandani Perspective: Room for a (Long) View DANIEL M. NEUMAN Abstract: A half century personal overview of my study of Hindustani musicians generally, and my teacher specifically provides the context and explanation for what I aver as the distinctive features of Hindustani music. First, the music practice did not require colonial reconfigurations from the perspective of its hereditary khandani practitioners. Second, for ethnomusicologists, the relationship between the researcher-disciple and consultant-master teacher was uniquely personal and loyal. Accordingly, despite exponentially expanding our understanding of its music practices in the last 50 years, ethnomusicological research in India remains remarkably free of generational friction, other than the necessary traction to learn more. Résumé : La vue d ’ ensemble acquise au bout d ’ un demi-siècle d ’ étude des musiciens hindoustanis en général, et celle transmise par mon professeur en particulier, fournissent 44 (1): 210-234. le contexte et l ’ explication de ce que j ’ affirme être les traits distinctifs de la musique hindoustani. Premièrement, du point de vue de ses praticiens khandani héréditaires, la pratique musicale n ’ a pas eu besoin de reconfigurations coloniales. Deuxièmement, pour les ethnomusicologues, la relation entre le disciple-chercheur et l ’ enseignant maître- MUSICultures consultant était uniquement personnelle et faite de loyauté. Par conséquent, bien que notre compréhension de ces pratiques musicales ait connu une croissance exponentielle au cours des cinquante -

World Music Performances

5TH ANNUAL MINI-CONFERENCE ON SCHOLARSHIP AND TEACHING Globalizing the Curriculum Sponsored by The Ohio State University Academy of Teaching Friday, May 6, 2011 150 Younkin Success Center World Music Program Featuring Faculty and Students from the OSU School of Music 12:45 pm Wart Hog #3 by Austin Wrinkle OSU Percussion Ensemble, Joseph Krygier, conductor Mike Dillman Mario Marini Brian Rhodus Andrew Hartman Johnny Mendoza Tim Shuster Amanda Lyon Ashley Williams *Kora Music Ryan Skinner, Kora *OSU Slavic Chorus Margarita Mazo, conductor Raag Mishra Kafi Hans Utter, Sitar River of Sorrow Tsun-Hui Hung, Erhu *African Drumming Ensemble Olivier Tarpaga, conductor *selections to be announced About Our Performers Tsun-Hui Hung holds a B.A. in Erhu performance from the Chinese Culture University, Taiwan, a M.A. music composition from Ohio University, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Cognitive Ethnomusicology at Ohio State University. Her research interests include the cross-cultural study of pitch processing in music and speech and rhythm processing in vocal and instrumental music. An artist in both solo and collaborative performances worldwide, Tsun-Hui has won many awards, including the Excellent Prize in the National Erhu Competition in Taiwan. She has performed many times in the National Concert Hall and National Opera House in Taiwan and has played with many major orchestras, including the Taipei Symphony Orchestra and the National Chinese Opera Company. Margarita Mazo, Professor and Distinguished Scholar, is internationally known for her research on Russian music. She has published on Russian vernacular traditions, music of Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and music and musical life in Post-Soviet Russia. -

Pedagogical Intervention in Indian Music Education

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 2 February 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Pedagogical Intervention in Indian Music Education 1Rakesh Paliwal ,Music Research Scholar 1Department of Music, 1Mohanlal Sukhadia University,Udaipur, India Abstract: For qualitative and quantitative desired learning outcome ,Indian Music Education under aegis of government policy followed all values for each group.All earlier policy issue are overridden with N.E.P. 2020.This study has been undertaken to investigate the objectives of Pedagogy in Indian Music Education using T.L.E. practices and procedure. This study is carried out to attain 21 st century skills in indian music education with new perspective on the classical contemporary practices and modern innovative practices with instructional approach.This article on Indian Music education intervene with new innovative measures and Leveraging tech usage by social media , I.C.T and A.I.. Index Terms – Teaching,Learning,Evaluation,leveraging,pedagogy, Channel,App,Leadership Lesson,Dashboard ,Database. I. Introduction Music Education in Emerging Trend has entered in 21 st century with social Media.Success Ratio of a Artist is determined with number of Articles Written (its Impact Factor,Peer Reviewed,Its Access as open),Number of Books (Acknowledged,written as author,written as co-author,,Reviewed,Released in pen drive,Released online,in press),Number of Interview.Cultural and social relevance in Music Education has many challenges that play Hide and seek .Like every question there exists a valid and reliable answer .Social Media has filled gap and acting as a boon in musical Educational Issues.In This article we focus on Music Education Challenges and find out next course of ease action. -

Here, Effect SIMCA Challenges the Copyright Board Right Constitution

INTERVIEW F George Brooks SOUND Sajid-Wajid REGULARS F Offbeat: Strum the Junk! Venue Watch: BOXFebruary 2011 I Volume 1 I Issue 7 I ` 150 Bflat, Bengaluru Watch Tower: Bengaluru ww Right E Clause and Here, Effect SIMCA challenges the Copyright Board Right constitution Now E Sing Along! Are we about to witness the boom of karaoke in the country? E E E Rajya Sabha MP, script writer, lyricist and now, crusader for the creative fraternity. Saptak, Javed Akhtar on why he is convinced the Baajaa Gaajaa Indian Copyright Act should be amended 2011 kicks off with interesting music fests across the country I Publisher’s Note SOUND Final Act? BOX n a few days’ time, on February 21, both Houses of the Indian parliament February 2011 I Volume 1 I Issue 7 Iwill reconvene for the Budget session. MASTHEAD It remains to be seen whether parliamentary business will be struck by the same state of paralysis that characterized the Winter session a few months back. However, indications are that the government has been goaded into a PUBLISHER Nitin Tej Ahuja more flexible and accommodative stance on the opposition’s main demand of [email protected] a JPC investigation into the telecom spectrum auction controversy. Therefore, EDITOR it is possible that we may have a normal parliamentary session. Of course, Aparna Joshi the word ‘normal’ is used here rather generously given our parliamentarians’ [email protected] propensity for drama and shenanigans. CREATIVE DIRECTOR Sajid Moinuddin www.hbdesign.in From the music industry’s perspective, the million dollar question undoubtedly is whether this session will see the coming into law of the very CORRESPONDENTS Anita Iyer contentious amendments to the Copyright Act. -

Of 66 RECORDINGS COLLECTED by DEBRA

Page 1 of 66 RECORDINGS COLLECTED BY DEBRA JAN BIBEL Current Date September 1, 2021 The personal preferential ratings (* to ****) are continually revised with repeated hearings over the years. Sequence of albums here does not match the sequence on the shelves, which is in correct order. International Musique du No: *** Ocora C 559005 Gagaku and Beyond **** Tokyo Gakuso Celestial Harmonies 13179 Gems from Foreign Lands *** Tokyo Gakuso Celestial Harmonies 13217 Tegoto ** Tomoko Sunazaki Fortuna 17068 Koto Music. Tadao Sawai Plays Michio Miyagi *** Playasound PS 65180 The Soul of the Koto *** Musicians of Ikuta-Ryu Lyrichord 7218 Japan. Splendor of the Koto *** Playasound PS 65131 Koto Music of Japan ** Zumi-Kai Group LaserLIght 12 184 Koto Classics **** Shinichi Yuize Nonesuch 511729 L’ Epopee des Heike ** Junko Ueda VDE CD-650 Sankyoku *** Ensemble Yonin No Kai Ocora C 560070 Japan/Traditional Vocal & Instrumental Music **** Ensemble Nipponia Nonesuch 72072 Kabuki & Other Traditional Music **** Ensemble Nipponia Nonesuch 72084 Kabuki and Jiuta-Mai Music *** Ethnic B 6809 Nagauta [Kabuki concert music] *** Ensemble Kineya Ocora C 560144 Melody of Japan/ Brightness of Summer *** King KICH 2128 Melody of Japan/Pathos of Autumn ** King KICH 2129 Melody of Japan/Stillness of Winter *** King KICH 2130 Melody of Japan/Joy of Spring *** King KICH 2127 Japanese Traditional Music Gagaku *** King KICH 2001 Nagaku (No) *** King KICH 2002 Kabuki *** King KICH 2003 Biwa *** King KICH 2004 Shakuhachi *** King KICH 2005 So (Koto) *** King KICH 2006 Sankyoku (ensemble) *** King KICH 2007 Shamisen I *** King KICH 2008 Shamisen II *** King KICH 2009 Percussion *** King KICH 2010 Japanese Dance Music *** King KICH 2022 Japanese Work Songs ** King KICH 2023 Music of Japanese Festivals ** King KICH 2028 Eternal Songs *** Agatsuma Domo 73049 En **** Agatsuma Domo 73072 Yasouemaki ** WagakkiBand Avex Music [.mp3] Spirit of Samurai. -

Master's Thesis

Conflict and Confluence: Constructing and Challenging Boundaries at the Ahiri Institute for Indian Classical Music and Dance Anna Marie Stirr Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2005 2 2005 Anna Marie Stirr All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………..…………..i Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………ii Introduction………………………………………………………………………..……1 Chapter 1: History, Classicism, Multiculturalism and Presentation…………..………. 7 The Development of Classicism………………………………………..………7 Recognition of Diversity………………………………………………..…..…13 Institutional Discourse: Official Presentation ……………………..………….16 Chapter 2: A Tradition of Innovation: Discourses in Performance ……..…………….25 Promoting the Future of Indian Music: Subashish Bhattacharya’s Press Kit Interview. ………………………………….………………………26 Passing on the Tradition: Shujaat Khan and Ghazal at Carnegie Hall…………………………………………………………………… 36 Outside Orthodox Expectations: Sridhar Shanmugam’s Choreography…………………………………………...……………. 45 Chapter 3: The Search for a Musical Universal: Fusion and Confusion …………..….53 “Masters of Spirit” at Joe’s Pub: Confusion ……………………………..……54 “Spirits of Egos” ………………………………………………..……..59 Possibilities for Inspiration ……………………………………..……..64 Spirituality, Indian Music, and Finding Universals……………………..……. 65 Perspectives on Spirituality ……………………………………..……..68 Enjoyment, Connection and the Possibility of Transcendence: A Social Act ….74 The Ahiri