Dalphinis and Robert Lee 20.9.2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments Received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2009-069

Comments received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2009-069 Outcome: Rejected Effective date: 2010-01-18 SIL International ISO 639-3 Registration Authority 7500 W. Camp Wisdom Rd., Dallas, TX 75236 PHONE : (972) 708-7400 FAX : (972) 708-7380 (GMT-6) E-MAIL : [email protected] INTERNET : http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/ Registration Authority decision on Change Request no. 2009-069: to rename the current code element [acf] “Saint Lucian Creole French” as “Martiniquan Creole French” The request to rename this code element from “Saint Lucian Creole French” to “Martiniquan Creole French” is rejected as being an issue within the scope of Ethnologue: Languages of the World , and not directly within the purview of the ISO 639-3 standard. The ISO 639-3 RA acknowledges the confusion concerning the relationship between the French creole used in Martinique and the French creole used in adjacent island nations of the Lesser Antilles, as described by the Ethnologue , 16 th ed. However, it seems that this issue is one to be corrected within the Ethnologue itself, to associate the language as spoken in Martinique with [acf] and not with [gcf], as it does currently. Discussion of this proposal (which, unfortunately, was not offered in the format of a formal comment to the RA), focused on two issues closely associated with this request: • The misrepresentation caused by referring to all the very closely associated creoles of the southern Lesser Antilles varieties (Martinique, St. Lucia, Dominica, Grenada, Trinidad and Tobago) by the name with which it is associated in a single country. -

1 a NEW LOOK at NASALIZATION in HAITIAN CREOLE* Albert Valdman

1 A NEW LOOK AT NASALIZATION IN HAITIAN CREOLE* Albert Valdman & Iskra Iskrova Indiana University 1. Introduction The status of nasal vowels in Haitian Creole (HC) and in French lexifier creoles in general has been the object of a considerable literature. However, its analysis has remained impervious to various types of phonological approaches. The nasal vowel system of HC has posed two major problems: (1) the determination of the total inventory; (2) the analysis of nasal vowels occurring in the context of adjacent or nearby other nasal segments. There is a further issue that has proven even more untractable: the analysis of nasalization phenomena occurring in the post-posed clitics, the third person singular pronoun li and the definite determiner la. Even more complex but relatively unexplored by phonologists are nasalization phenomena associated with the possessive pronoun in northern varieties of the language, for example [papam]~ alternating with [paparam]~ and [papa a mwe~] 'my father', [dwa~m] alternating with [do a mwe~] 'my back' (Valdman 1978). The maximal inventory of nasal vowels of HC comprises five units; its major differences with that of Referential French (RF) is the presence of a pair of high vowels and the absence of the front rounded vowel, see Table (1). There are also significant differences in the phonetic characteristics of the various phonemes that will not be dealt with here. (1) Nasal vowel inventories of HC and RF Haitian Creole Referential French i~ u~ e~ ä~ ∞~ œ~ o~ a~ a~ *We owe a debt of gratitude to our colleague Stuart Davis who generously provided advice and counsel on theoretical issues; of course, only we as authors are responsible for the application of his suggestions to this specific analysis. -

Samuel Selvon and Linton Kwesi Johnson

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea From the Caribbean to London: Samuel Selvon and Linton Kwesi Johnson Relatrice Laureanda Prof.ssa Annalisa Oboe Francesca Basso n° matr.1109406 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2015 / 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................................................... 3 FIRST CHAPTER - HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ............................. 5 1. The Rise and the Fall of the British Empire: An Overview ..........................5 2. Caribbean Migration to Great Britain: From the 1950s to the 1970s .............9 3. White Rejection: From the 1950s to the 1970s........................................... 12 SECOND CHAPTER - THE MIGRANT FROM THE CARIBBEAN .. 19 1. Identity ..................................................................................................... 19 1.1. Theoretical Overview ....................................................................... 19 1.2. Caribbean Identity ............................................................................ 21 2. Language .................................................................................................. 29 3. “Colonization in Reverse” ......................................................................... 37 THIRD CHAPTER - SAMUEL SELVON............................................... 41 1. Biography ................................................................................................ -

Passivization and the Cognitive Complexity Principle in Wes: the Case of Finite and Non-Finite Complementation Clauses

Passivization and the Cognitive Complexity Principle in WEs: The case of finite and non-finite complementation clauses Noura Abdou (Regensburg University, Germany) Rohdenburg (1996:149) investigates the role played by processing complexity in the choice between grammatical alternatives in present day English. He lists passive constructions among cognitively more complex contexts where more explicit variants tend to be favored. In this respect, my present work adds to previous research by testing the effect of Rohdenburg’s complexity principle (1996:151) on the envelop of variation between finite and non-finite complementation clauses (CCs) in terms of the use of passivized verbs in the CCs of verb hope across five varieties of English; namely British and American English (as norm-providing ENL varieties) and Singapore, Indian, and Philippine English (as nativized L2 varieties of English). Furthermore, previous research (e.g. Leech et al. 2009, Seoane and Williams 2006) has shown that there is a decreasing tendency of be-passive in British and American English academic writing in the second half of the 20th century. This considered, my results will show whether the tendency towards higher use of active voice can also be found in the CCs of hope. The present study aims to: 1) examine the distribution of finite (that-clause, zero-complementizer clause) and non-finite (to-infinitive) CCs in the previously mentioned varieties, and 2) shed more light on the reasons that might have contributed to the infrequent use of the passive construction in the CCs of hope across these varieties; such as the recurrent use of first person pronouns (Hundt and Mair 1999), the colloquialization of written English (Mair and Leech 2006), etc. -

Creole Discourse and Social Development

IDRC-M R212e CREOLE DISCOURSE AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT LaW"ence D. tarrington Material contained in this report is produced as submitted and has not been subjected to peer review or editing by IDRC Communications Division staff. Mention of proprietary ncJlles does not constitute endorsenent of the product and is given only for infonnation. ©1988 Lawrence D. Carrington CONTENTS Pref ace 1 Creoles in the societies under study 6 St. Lucia: Creole within public life 13 Dominica: Creole within public life 22 The French Departments 26 Haiti and Haitian 32 The question of instrumentalization 37 Considerations in the formal use of the vernaculars 44 The areas of action 49 The available scholarship and technical resources 54 Bibliography 60 Conclusion 81 Notes and references 82 Appendix 1 News and information 85 Appendix 2 Agricultural information 87 Appendix 3 Health education 91 Appendix 4 Adult literacy 94 Appendix 5 Original project document 96 Appendix 6 Institutions at which studies on Antillean are in progress 102 1 I PREFACE The history of the project The project which has come to be known as Creole Discourse and Social Development had its beginnings in a series of conversa tions between Jean Casimir, Social Affairs Officer, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and Lawrence Carrington, Senior Research Fellow, Faculty of Educa tion, University of the West Indies (UWI). The pair attended together the 3eme Colloque International des Etudes Creoles held in St. Lucia in May of 1981. Exchanges related to the instru mental ization of vernacular languages led Casimir and Carrington to elaborate their ideas on the mobilization of vernacular languages in the development of Caribbean states. -

Out of Africa

Out of Africa African influences in Atlantic Creoles Mikael Parkvall 2000 Battlebridge Publications i This volume is dedicated to the memory of Chris Corne and Gunnel Källgren two of my main sources of inspiration and support during the preparation of this thesis who sadly died before its completion. Published by: Battlebridge Publications, 37 Store Street, London WC1E 7QF, United Kingdom Copyright: Mikael Parkvall November 2000 <[email protected]> All rights reserved. ISBN 1-903292-05-0 Cover design: Mikael Parkvall Printed by Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Brunel Road, Totton, Hampshire, SO40 3WX, UK. ii Contents Map showing the location of the Atlantic Creoles viii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Aim and scope of the study 2 1.2 Methodology 1.2.1 Defining substrate influence 3 1.2.2 Choice of substrate languages 3 1.2.3 Sources used 5 1.2.4 Other issues 9 1.3 Terminological issues and transcription conventions 9 1.3.1 Names of contact languages 9 1.3.2 Names of African languages 10 1.3.3 Names of geographical regions 11 Map of geographical regions involved in the slave trade 12 1.3.4 Linguistic terminology 12 Map of the locations where selected African languages are spoken 13 1.3.5 Transcription of linguistic examples 13 1.3.6 Abbreviations and symbols used 14 1.4 Acknowledgements 15 2. Epistemology, methodology and terminology in Creolistics 16 2.1 First example: Universals, not substrate 20 2.2 Second example: Again universals, not substrate 21 2.3 Third example: Lexifier, not substrate or universals 22 2.4 Fourth example: Substrate, not lexifier 23 2.5 Conclusion 24 3. -

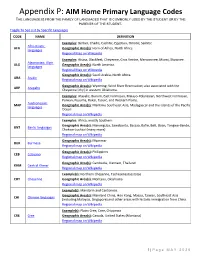

Appendix P: AIM Home Primary Language Codes the LANGUAGE IS from the FAMILY of LANGUAGES THAT IS COMMONLY USED by the STUDENT OR by the PARENTS of the STUDENT

Appendix P: AIM Home Primary Language Codes THE LANGUAGE IS FROM THE FAMILY OF LANGUAGES THAT IS COMMONLY USED BY THE STUDENT OR BY THE PARENTS OF THE STUDENT. Toggle To See List by Specific Languages CODE NAME DEFINITION Examples: Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian, Omotic, Semitic. Afro-Asiatic AFA Geographic Area(s): Horn of Africa, North Africa. languages Regional Map on Wikipedia Examples: Atsina, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Gros Ventre, Menominee, Miami, Shawnee. Algonquian; Algic ALG Geographic Area(s): North America. languages Regional Map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Saudi Arabia, North Africa. Arabic ARA Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Wyoming: Wind River Reservation; also associated with the ARP Arapaho Cheyenne [chy] in western Oklahoma. Examples: Atayalic, Bunum, East Formosan, Malayo-Polynesian, Northwest Formosan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Tsouic, and Western Plains. Austronesian MAP Geographic Area(s): Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar and the islands of the Pacific languages Ocean Regional map on Wikipedia Examples: Africa, mostly Southern Geographic Area(s): Manenguba, Sawabantu, Bassaa, Bafie, Beti, Boan, Tongwe-Bende, BNT Bantu languages Chokwe-Luchazi (many more) Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Myanmar BUR Burmese Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Philippines CEB Cebuano Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand KHM Central Khmer Regional map on Wikipedia Example(s): Northern Cheyenne, Tsehesenestsestotse CHY Cheyenne Geographic Area(s): Montana, -

The Sentence of Guadeloupean Creole

To mum, dad, Matteo and Filippo. And to all the people who think that the difference between a language and a dialect has something to do with linguistics considerations, whereas it is only a matter of political and economical power. Don't be ashamed of speaking the idiom that best reflects your inner self. “Pa obliyé, tout biten ka évoliyé. […] Avan lang fwansé té tin Laten. Laten, kon manmanpoul kouvé zé a-y é éklò : Pangnòl, Italyen, Fwansé, Pòwtigè... Lè yo vin manman, yo fè pitit osi : fwansé fè kréyòl, Pòwtigè fè Brézilyen, Pangnòl fè Papamiento... Pa obliyé on tipoul sé on poul ki piti é poulòsdonk kréyòl kon fwansé sé on lang.” [Moïse, 2005] Table of contents i. Acknowledgements ….............................................................................................11 ii. English Abstract ….................................................................................................13 iii. Italian Abstract …..................................................................................................14 iv. Symbols ….............................................................................................................15 Introduction …..........................................................................................................19 PART 1: ON CREOLE LANGUAGES AND GUADALOUPEAN CREOLE Chapter 1: On Creole languages ….........................................................................25 1.1 Pidgins and Creole languages …..........................................................................25 1.2 -

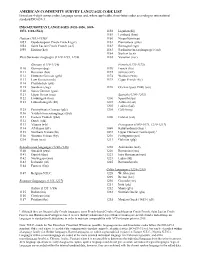

American Community Survey Language Code List

AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY LANGUAGE CODE LIST Listed are 4-digit census codes, language names and, where applicable, three-letter codes according to international standard ISO 639-3. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (1053-1056, 1069- 1073, 1110-1564) 1158 Ligurian (lij) 1159 Lombard (lmo) Haitian (1053-1056)1 1160 Neapolitan (nap) 1053 Guadeloupean Creole French (gcf) 1161 Piemontese (pms) 1054 Saint Lucian Creole French (acf) 1162 Romagnol (rgn) 1055 Haitian (hat) 1163 Sardinian (macrolanguage) (srd) 1164 Sicilian (scn) West Germanic languages (1110-1139, 1234) 1165 Venetian (vec) German (1110-1124) French (1170-1175) 1110 German (deu) 1170 French (fra) 1111 Bavarian (bar) 1172 Jèrriais (nrf) 1112 Hutterite German (geh) 1174 Walloon (wln) 1113 Low German (nds) 1175 Cajun French (frc) 1114 Plautdietsch (ptd) 1115 Swabian (swg) 1176 Occitan (post 1500) (oci) 1120 Swiss German (gsw) 1121 Upper Saxon (sxu) Spanish (1200-1205) 1122 Limburgish (lim) 1200 Spanish (spa) 1123 Luxembourgish (ltz) 1201 Asturian (ast) 1202 Ladino (lad) 1125 Pennsylvania German (pdc) 1205 Caló (rmq) 1130 Yiddish (macrolanguage) (yid) 1131 Eastern Yiddish (ydd) 1206 Catalan (cat) 1132 Dutch (nld) 1133 Vlaams (vls) Portuguese (1069-1073, 1210-1217) 1134 Afrikaans (afr) 1069 Kabuverdianu (kea) 1 1135 Northern Frisian (frr) 1072 Upper Guinea Crioulo (pov) 1 1136 Western Frisian (fry) 1210 Portuguese (por) 1234 Scots (sco) 1211 Galician (glg) Scandinavian languages (1140-1146) 1218 Aromanian (aen) 1140 Swedish (swe) 1220 Romanian (ron) 1141 Danish (dan) 1221 Istro Romanian (ruo) -

An Inside Look at Gullah: What Makes It Distinctive David B Frank1

Paper presented on March 10, 2017, at the 84th Meeting of the Southeastern Conference on Linguistics, College of Charleston. An Inside Look at Gullah: What Makes it Distinctive David B Frank1 0. Introduction As a linguist, I value diversity. The theme of this conference is to consider “underrepresented linguistic varieties in the Lowcountry and beyond,” and that fits very well with my interest in Gullah and other creole languages. As a linguist, I don’t consider there to be any “incorrect” or substandard language forms. They are all fascinating and valued. (Well, to tell the truth, sometimes I make private judgments, such as when I hear someone say “just between you and I….”) Sociolinguistically-speaking, one’s attitude toward linguistic forms will tend to match one’s attitude toward the people that use those forms. If you tell someone (at least outside of the academic setting) that you are a linguist, you will probably get asked the same question I get asked: “How many languages do you speak?” You can hardly blame them for asking, because in some contexts such as the military, a linguist is defined as someone who learns to speak one or more other languages. I usually say that while I speak some Spanish and French, linguistics involves a study of the principles of language in general. In the process of trying to understand the nature of language in general, we are exposed to bits of lots of different languages. But I add that I have a special interest in creole languages, and three specific languages that I have focused on and can speak with some degree of fluency are French Creole as spoken on the island of Saint Lucia, Gullah (an English Creole), and the Portuguese Creole spoken in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. -

Gullah Grammar Sketch David B Frank SIL International 0

Paper written for and presented on September 25, 2015, at the Centennial Conference of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History in Atlanta. Gullah Grammar Sketch David B Frank SIL International 0. Introduction The name Gullah pertains to a language and a culture with a distinct heritage centered in the southeastern US along the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia, but extending into the southern coastal area of North Carolina and the northern coastal area of Florida. The name Geechee is preferred as a cultural identifier in some places, particularly in Georgia; and to show the unity of the culture, the combined name Gullah Geechee is now often used. Probably the name Gullah came from that of the Gola people in coastal western Africa, whose language and culture pre-date the modern names of the countries they still inhabit, namely Liberia and Sierra Leone.1 The first published application of that name to a language2 is John Bennett’s 1908 article in the South Atlantic Quarterly titled “Gullah: A Negro Patois,” which starts out, “There is a patois spoken in the mainland and island regions, bordering the South Atlantic Seaboard, so singular in its sound as constantly to be mistaken for a foreign language. It is found in no other portion of the South. Ordinary negro dialect found in books has no resemblance to it.” In 1926, Reed Smith wrote a booklet called “Gullah,” published as Bulletin of the University of South Carolina number 190. He wrote, “The term Gullah is a little-known word for a less-known people.