Cultivating Femininity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

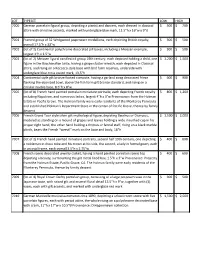

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Estudo E Desenvolvimento Do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Juvane Nunes Marciano Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 Juvane Nunes Marciano Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação do Departamento de Informática e Matemática Aplicada da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte como requisito final para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Sistemas e Computação. Linha de pesquisa: Engenharia de Software Orientador Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda PPGSC – PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO DIMAP – DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA CCET – CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA UFRN – UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 UFRN / Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Marciano, Juvane Nunes. Aprendizagem da língua japonesa apoiada por ferramentas computacionais: estudo e desenvolvimento do jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders. / Juvane Nunes Marciano. – Natal, RN, 2014. 140 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Terra. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação. 1. Informática na educação – Dissertação. 2. Interação humano- computador - Dissertação. 3. Jogo educacional - Dissertação. 4. Kanas – Dissertação. 5. Hiragana – Dissertação. 6. Roma-ji – Dissertação. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Japanese Economic Growth During the Edo Period*

Japanese Economic Growth during the Edo Period* Toshiaki TAMAKI Abstract During the Edo period, Japanese production of silver declined drastically. Japan could not export silver in order to import cotton, sugar, raw silk and tea from China. Japan was forced to carry out import-substitution. Because Japan adopted seclusion policy and did not produce big ships, it used small ships for coastal trade, which contributed to the growth of national economy. Japanese economic growth during the Edo period was indeed Smithian, but it formed the base of economic development in Meiji period. Key words: Kaimin, maritime, silver economic growth, Sakoku 1.Introduction Owing to the strong influence of Marxism, and Japan’s defeat in World War II, Japanese historians dismissed the Edo period (1603–1867) as a stagnating period. Japan, during this period, was regarded as a country that lagged behind Europe because of its underdeveloped social and economic systems. It had been closed to the outside world for over two hundred years, as a result of its Sakoku (seclusion) policy, and could not, therefore, progress as rapidly as Europe and the United States. This image of Japan during the Edo period began to change in the 1980s, and this period is now viewed as an age of economic growth, even if Japan’s growth rates were not as rapid as those of Europe. Economic growth during the Edo period is now even considered to be the foundation for the economic growth that occurred after the Meiji period. In this paper, I will develop three arguments that demonstrate the veracity of the above viewpoint. -

Alcock and Harris. Foreign Diplomacy in Bakumatsu Japan Author(S): John Mcmaster Reviewed Work(S): Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol

Alcock and Harris. Foreign Diplomacy in Bakumatsu Japan Author(s): John McMaster Reviewed work(s): Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 22, No. 3/4 (1967), pp. 305-367 Published by: Sophia University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2383072 . Accessed: 07/10/2012 12:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Sophia University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Monumenta Nipponica. http://www.jstor.org Alcock and Harris FOREIGN DIPLOMACY IN BAKUMATSU JAPAN by JOHN MCMASTER T W ENTY-ONE timesthe guns shattered the noonday quiet of Edo Bay. As they roared, thered-ball flag ofJapan was hoisted to join what Japanese called the flowery flag of theAmericans. It wasJuly 29th, the year was i858and the warship was acknowl- edgingthat a commercialtreatyhadjust been signed on board. The roar, the smoke and the shudderthroughout the wooden ship was appropriate. The proximatecause of the treaty hadbeen cannon. Although theJapanese then had no ship to match the "Powhattan," the solitaryvessel was notas importantas thenews she had brought from Shanghai. Other foreignvessels were on theway to Japan, not alone but in fleets.A Britishsquadron was to be followedby a French,both fresh from forcing treaties upon China. -

Westernization in Japan: America’S Arrival

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-3, Issue-8, Aug.-2017 http://iraj.in WESTERNIZATION IN JAPAN: AMERICA’S ARRIVAL TANRIO SOPHIA VIRGINIA English Literature Department BINUS UNIVERSITY Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- As America arrived with westernization during late Edo period also known as Bakumatsu period, Japan unwelcomed it. The arrival of America in Japan had initiated the ‘wind of change’ to new era towards Japan culture albeit its contribution to Japan proffers other values at all cost. The study aims to emphasize the importance of history in globalization era by learning Japan's process in accepting western culture. By learning historical occurrences, cultural conflicts can be avoided or minimized in global setting. The importance of awareness has accentuated an understanding of forbearance in cultural diversity perspectives and the significance of diplomatic relation for peace. Systematic literature review is applied as the method to analyze the advent of America, forming of treaty, Sakoku Policy, Diplomatic relationship, and Jesuit- Franciscans conflict. The treaty formed between Japan and America served as the bridge for Japan to enter westernization. Keywords- Westernization, Japan, America, Sakoku Policy, Jesuit-Franciscans Conflict, Treaty, Culture, Edo Period. I. INTRODUCTION Analysing from the advent of America leads to Japan’s Sakoku Policy which took roots from a Bakumatsu period or also known as Edo period, dispute caused by westerners when Japan was an specifically in the year of 1854 in Capital of Kyoto, open country. This paper provides educational values Japan, was when the conflict between Pro-Shogunate from historical occurrences. -

Torture, Forced Confessions, and Inhuman Punishments: Human Rights Abuses in the Japanese Penal System

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Torture, Forced Confessions, and Inhuman Punishments: Human Rights Abuses in the Japanese Penal System Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/63f7h7tc Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 20(2) Author Vize, Jeff Publication Date 2003 DOI 10.5070/P8202022161 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TORTURE, FORCED CONFESSIONS, AND INHUMAN PUNISHMENTS: HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN THE JAPANESE PENAL SYSTEM Jeff Vize* INTRODUCTION Japan has rarely found itself on the most-wanted lists of human rights activists, and perhaps for good reason. It is the richest and most stable nation in Asia,' and seems to practice none of the flagrantly abusive policies of regional neighbors like China2 or Myanmar. 3 Its massive economy provides a high stan- dard of living. 4 Crime, though rising rapidly in the last ten years, is still minuscule by international standards. In 2000, Japanese authorities reported that there were 1,985 crimes for every 100,000 inhabitants, compared to 4,124 in the United States, and * University of California at Davis, King Hall School of Law, J.D. (2004). The author would like to thank Professor Diane Marie Amann for her helpful advice, comments, and criticism. The author would also like to thank Professor Kojiro Sakamoto, and his wife Chikage, for their advice from a Japanese perspective. 1. JAPAN'S NEW ECONOMY: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY 2-3 (Magnus Blomstrom et al. eds., 2001). See also Statistics Division, United Nations, Indicators on Income and Economic Activity, at http://un- stats.un.org/unsd/demographic/social/inc-eco.htm (last visited July 27, 2003) (listing Japan's per capita gross domestic product for 2001 at $32,540, the fifth highest in the world). -

The Kata of Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu

The Kata of Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu Shoden Level or Omori-ryu There are three levels of Iai (aware and ready) kata (formal techniques) in Eishin ryu. The first or shoden level consist of eleven forms developed by Omori Rokurozaemon, a student of Hasegawa Eishin and an expert in Shinkage Ryu kenjutsu. With the unification of Japan the samurai had no wars to fight (1615-1867). Omori combined a series of sword drawing exercises with the etiquette of the tea ceremony to create the formal Seiza Kata. This was the birth of ‘Iaido’ where techniques of self-defense became techniques of self-development. These kata are used for grading for second dan and above in the All United States Kendo Federation. They are called the koryu kata, which means classical martial traditions or ancient forms. All but one, Oikaze, begin from the seiza (kneeling) position. The O chiburi (blood throw) is done standing with the feet together. Present Name English meaning and explanation of technique 1. Mae Front The enemy is in seiza before you when he goes for his sword. 2. Migi Right You is facing right and your enemy is in seiza at your left. 3. Hidari Left You are facing left and your enemy is in seiza at your right. 4. Ushiro Rear You are facing the rear and the enemy is in seiza behind you. 5. Yaegaki Barriers within Your enemy survives your first over head cut and plays possum barriers until you begin noto. As he attacks again, you move back and draw to block a cut to the leg and counter-attack with kirioroshi. -

Nook 1St Generation Or Nook Simpletouch, Sony Reader, Kobo)

How to Download eBooks to Your Black & White eInk eReader (Nook 1st Generation or Nook SimpleTouch, Sony Reader, Kobo) Warren Public Library You will need: . A Warren Public Library Card . PC or Mac computer . Black & White eReader (Nook 1st Generation or Nook . Adobe Digital Editions software SimpleTouch, Sony Reader, Kobo Reader) and a USB cable to attach it to your computer Note: Before you can checkout eBooks for your eReader, you will need to download and install Adobe Digital Editions. For instructions on how to do this, see page 3. 1. In a web browser on your computer, go to our OverDrive site at http://ebooks.mcls.org. 2. Near the upper right, click Sign In. Select Warren Public Library from the dropdown menu. Enter your Library card number. Click the green Sign In button. 3. Using the search box on the right-hand side, search for the title or author you are looking for. To narrow your results to titles usable by your eReader, in the left-hand side menu under Format click Adobe EPUB eBook. Click the title of the book you wish to checkout. 4. To check out your EPUB eBook, click “Borrow”. The EPUB eBook will be checked out to you. If the EPUB eBook is not currently available to be checked out, instead of saying “Borrow” it will say “Place a Hold”. To put an item on hold, click the “Place a Hold” button. Enter your email address in the boxes where indicated. You will get an email when the item is available to be checked out, and will have 72 hours from when the email is sent to checkout and download your hold. -

Ws \\ I: I, I; I\ Si

x i: w s \\ i: i, i; i\ s i: FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAJOR EXHIBITION OF JAPANESE ART AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Exhibition To Appear Only In Washington WASHINGTON, August 25, 1988- The art of the daimyo, feudal lords who ruled the provinces of Japan for nearly 700 years, will be the focus of a new exhibition, Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185 - 1868, opening this fall at the National Gallery of Art. The exhibition will bring together more than 450 Japanese-owned works of art that express the values that helped shape the aesthetic ideals and social character of the Japanese nation in its feudal age. An unprecedented number of objects officially designated by the Japanese government as National Treasures, Important Cultural Properties and Important Art Objects will be on view in what will be the largest exhibition of its kind ever presented in the West, or even in Japan. This exhibition will appear only in Washington. Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185 - 1868 will be in the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, Oct. 30, 1988 through Jan. 23, 1989. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, The Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, and The Japan Foundation. The R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, The Yomiuri Shimbun and The Nomura Securities Co., Ltd. made the exhibition possible. Japan Air Lines provided transport. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.