It All Started with Kapteyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Rörande Uppsala Universitet B

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter rörande Uppsala universitet B. INBJUDNINGAR, 192 Redaktör: Per Ström Bild- och uppsatsredaktion: Carl Frängsmyr Layout: Grafisk service Vinjetter: Tryggve Nevéus Omslagsbild: Carolina Rediviva i vinterdräkt sett från söder. Gouache av Eric Österlund från 1800-talets andra hälft. Uppsala universitetsbibliotek. ISSN 0566-3091 ISBN 978-91-513-0829-6 Sättning: Grafisk service, Uppsala universitet Tr yck: DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2020 Kontakt med redaktionen Förfrågningar kring distribution och abonnemang, till exempel rörande levererad upplagas storlek eller önskemål om erhållande av seriens skrifter, riktas till redaktionen under följande e-postadress: [email protected] Promotionsfesten i Uppsala den 31 januari 2020 med Uppsala universitets inbjudningsskrifter 1844–2019. 175-årsregister över däri publicerade uppsatser, dokument, förordningar och biographica Sammanställt och försett med inledning av Carl Frängsmyr Innehåll Uppsala universitets inbjudningsskrifter 1844–2019. 175-årsregister över däri publicerade uppsatser, dokument, förordningar och biographica. Sammanställt och försett med inledning av Carl Frängsmyr 9 Program 75 Processionsordning 76 Promotionsarrangemang 77 Rektors hälsningsord 79 Universitetets och fakulteternas inbjudan 81 Promotorernas presentationer Teologiska fakulteten, av Mia Lövheim 83 Juridiska fakulteten, av Charlotta Zetterberg 85 Medicinska fakulteten, av Ulf Gyllensten 87 Farmaceutiska fakulteten, av Anna Orlova 89 Historisk-filosofiska fakulteten, avSven -

European Southern Observatory Bulletin No. 1

EUROPEAN SOUTHERN OBSERVATORY BULLETIN NO. 1 The Governments of Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden have signed a Convention1) concerning the erection of a powerful astronomical observatory on Oetober 5, 1962. Ey this Convention a European organization for astronomic:ll researd1 in the SOllthern Hemisphere is created. The purpose of this organization is the con strllction, equipment, and operation of an astronomical observatory situated in the Southern Hemisphere. The initial program comprises the following sllbjects: 1. a 1.00 m photoelectrie tele cope, 2. a 1.50 m speetrographic tcleseope, 3. a 1.00 m Sd1midt telescope, 4. a 3.50 m tele cope, 5. allxiliary equipment neeessary to carry out research programs, 6. the buildings necessary to shelter the scientific equipment as weil as the administration of the observatory and the housing of personnel. The site of the observatory will be in the middle between the Pacific coast and the high duin of the Andes, 600 km north of Santiago de Chile, on La Silla. ') The ESO Management will on rcquest readily provide for copie, of ,he Pari, Convclllion of 5 Oetober 1962. Organisation Europeenne pour des Recherehes Astronomiques dans l'Hemisphere Austral EUROPEAN SOUTHERN OBSERVATORY BULLETIN NO. 1 November 1966 Edited by European Southern Observatory, Office of the Director 21 Am Bahnhof, 205 Hamburg 80, Fed. Rep. of Germany ESO BULLETIN NO. 1 CONTENTS O. Heckmann: Foreword 5 J. Ramberg: Bertil Lindblad 7 A doeument eoneerning the astronomical eomparison between South Afriea and Chile ................ 9 H. Siedentopf: Comparison between South Afriea and Chile 11 A. -

Biography of Horace Welcome Babcock

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES H O R ACE W ELCOME B A B COC K 1 9 1 2 — 2 0 0 3 A Biographical Memoir by GEO R G E W . P R ESTON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2007 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. Photograph by Mount Wilson and Los Campanas Observatories HORACE WELCOME BABCOCK September 13, 1912−August 29, 2003 BY GEORGE W . P RESTON ORACE BABCOCK’S CAREER at the Mount Wilson and Palomar H(later, Hale) Observatories spanned more than three decades. During the first 18 years, from 1946 to 1964, he pioneered the measurement of magnetic fields in stars more massive than the sun, produced a famously successful model of the 22-year cycle of solar activity, and invented important instruments and techniques that are employed throughout the world to this day. Upon assuming the directorship of the observatories, he devoted his last 14 years to creating one of the world’s premier astronomical observatories at Las Campanas in the foothills of the Chilean Andes. CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION Horace Babcock was born in Pasadena, California, the only child of Harold and Mary Babcock. Harold met Horace’s mother, Mary Henderson, in Berkeley during his student days at the College of Electrical Engineering, University of California. After brief appointments as a laboratory assis- tant at the National Bureau of Standards in 1906 and as a physics teacher at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1907, Horace’s father was invited by George Ellery Hale in 1908 to join the staff of the Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO), where he remained for the rest of his career. -

Le Prague Astronomtque Accueille 2900 Astronomes Do Monde Entier

DISSERTATIO PRAGAE CVM MCMLXVII 20. VIII. Series Secunda Lett r e au Rédacteur e n Chef du Nuncius Sidereus MON CHER AMI, Sur Ia foi du Président qui affjrme que j'écris plus de 3.300 lettres par an pour le seul service de l'UAI, ou peut-être en raison des contributions passées aux journaux des Assemblées Générales, par exemple à ce Kosmos [ Moscou, 1958), où, avec mon vieux complice Schatzman, nous avons émis des idées définitives ( qu'en reste-t-ll?) sur !a structure de l'UAI, vous me demandez. .. Sonnerie de telephone. Bxcusez cette lettre m terrompue: c'était un astro nome cannois qui auait vu hier soir un objet céleste; et est-ce que je pourrais lui dire sz? et est-ce que ;e ne pensais pas que peut-etre? des extra-terrestres? et.... d'ailleurs il a vu des hublots très distinctement! .. vous me demandez done quelques mots pour le Nuncius Sidere us, pour y parler des droits et des devoirs d'un Secrétaire Général... Beau sujet, s'il en est. La grandeur de ... .. Excusez cette nouvelle interruption. On frappe à la porte. Il faut signer le courrier du jour. «With all good wishes». «With all good wishes, sincerely yours». «With all good wishes, sincerely yours». Ah non, pas d celui-là! Tl n'est pas assez gentil avec moi. On mettra «sincerely yours», s1mplement. Bien. A demain, Christiane {voir figure no 1}. Et reprenons ma lettre inter rompue. Je disais done !'exaltation du Secrétaire Général, lorsqu'!l considère, avec le supreme detachement auquel il peut pretendre, aus-dessus de Ia mêlée, les developpernents excitants de notre si belle science. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Rörande Uppsala Universitet B

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter rörande Uppsala universitet B. INBJUDNINGAR, 189 Redaktör: Per Ström Bild- och uppsatsredaktion: Carl Frängsmyr Layout: Grafisk service Vinjetter: Tryggve Nevéus Omslagsbild: Carl Wilhelmsons inspektorsporträtt av Arvid G. Högbom, Norrlands nation. Jämför sidan 16. Fotograf: Mikael Wallerstedt.. ISSN 0566-3091 ISBN 978-91-513-0525-7 Sättning: Grafisk service, Uppsala universitet Tr yck: DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2019 Kontakt med redaktionen Förfrågningar kring distribution och abonnemang, till exempel rörande levererad upplagas storlek eller önskemål om erhållande av seriens skrifter, riktas till redaktionen under följande e-postadress: [email protected] Promotionsfesten i Uppsala den 25 januari 2019 Innehåll Om Arvid G. Högboms Självbiografiska anteckningar. Av Carl Frängsmyr 7 Självbiografiska anteckningar. AvArvid G. Högbom 15 Personförteckning 73 Program 81 Processionsordning 82 Promotionsarrangemang 83 Rektors hälsningsord 85 Universitetets och fakulteternas inbjudan 87 Promotorernas presentationer Teologiska fakulteten, av Mattias Martinson 89 Juridiska fakulteten, av Minna Gräns 91 Medicinska fakulteten, av Anna Rask-Andersen 93 Farmaceutiska fakulteten, av Per Andrén 95 Historisk-filosofiska fakulteten, avErik Carlson 97 Språkvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Mats Eskhult 99 Samhällsvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Lars Magnusson 101 Utbildningsvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Ann-Carita Evaldsson 103 Teknisk-naturvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Gunilla Kreiss 105 Kortfattat promotionslexikon -

Nvncio Sidereo Iii 4

D IS SERTATIO CVM NVNCIO SIDEREO III 4 PRAGAE MMVI 17. VIII. SERIES TERTIA Today's invited discourse at 6:15 p.m. in the Congress Hall Zdeněk Švestka – 40 years as an editor of Solar Physics Address of František Fárník at the yesterday’s celebratory lunch DISCOURSE The magnetic fi eld and its effects on the solar Ladies and gentlemen, dear colleagues, atmosphere in high resolution I was honored by the suggestion of Lídia to say a few words about Zdeněk during INVITED Alan Title, Stanford-Lockheed Institute for Space Research this occasion, focusing on his contribution to solar physics in general. It is a pleasure S ' in the fi rst place but, at the same time, a very diffi cult task for me. I am sure that To resolve the effects of the magnetic fi eld it is necessary to image the interior and speaking about Zdeněk’s scientifi c work for a group of solar physicists is like “carrying TODAY measure its rotation and fl ow systems; track the responses of the magnetic fi elds to fl ows in the surface; and to follow the coals to Newcastle”. Therefore, allow me to be brief about science and to add some personal reminiscences too. Because I am one generation younger, I came to our OF evolution of structures in the corona. Because the Sun is dynamic, both high spatial and temporal resolution are essential. Since the Sun’s magnetic fi eld effects encompass the entire spherical exterior, the entire surface and outer atmosphere Institute in Ondřejov after Zdeněk had to emigrate in 1971 and that’s why we met for must be mapped. -

Notable Scientists

NOTABLE SCIENTISTS A TO Z OF SCIENTISTS IN SPACE AND ASTRONOMY DEBORAH TODD AND JOSEPH A. ANGELO,JR. A TO Z OF SCIENTISTS IN SPACE AND ASTRONOMY Notable Scientists Copyright © 2005 by Deborah Todd and Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Todd, Deborah. A to Z of scientists in space and astronomy / Deborah Todd and Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. p. cm.—(Notable scientists) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4639-5 (acid-free paper) 1. Astronomers—Biography. 2. Space sciences—Biography. I. Angelo, Joseph A. II. Title. III. Series. QB35.T63 2005 520'.92'2—dc22 2004006611 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. Toro Cover design by Cathy Rincon Chronology by Sholto Ainslie Printed in the United States of America VB TECHBOOKS 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. “I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of stars makes me dream.” —Vincent Van Gogh “All of us are truly and literally a little bit of stardust.” —William Fowler To the loves on this very tiny planet who have sprinkled their stardust into my life and believed in my dreams. -

Messenger-No54.Pdf

MESSENGER No. 54 - December 1988 ESO'S EARLY HISTORY, 1953-1975 I. STRIVING TOWARDS THE CONVENTION ADRIAAN BLAAUW*, Kapteyn Laboratory, Groningen L'astronomie est bien I'ecale de la patience. From a letter by A. Danjon to J. H. Oort, 21 September 1962. A Historical Statement vention between five of these six coun be replaced by joint effort. As my col On January 26, 1954 twelve leading tries - Great Britain went its own way league and friend Charles Fehrenbach astranomers fram six European coun signed on 5 October 1962. By that time used to say: "11 faut faire I'Eurape." It tries issued the historical statement we almost ten years had passed since the also was a time at which some of the reproduce here [1]. It carries the sig notion of a joint Eurapean observatory Eurapean countries . had to deal with natures of Otto Heckmann and Albrecht had been expressed for the first time. serious internal problems. Governments Unsöld of the German Federal Republic, Another year and three months would as weil as astronomers had to face this. Paul Bourgeois fram Belgium, Andre have to elapse until the impatient hands It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Couder and Andre Danjon fram France, of the astranomers would be free to lay the first instigation towards the joint Roderick Redman fram Great Britain, the first solid foundations for the erec effort which would become ESO, had to Jan Oort, Pieter Oosterhoff and Pieter tion of the observatory. The date is come from one who, although rooted in van Rhijn from the Netherlands, and January 17, 1964 when, with the com European ancestry, had been an on Bertil Lindblad, Knut Lundmark and pletion of aseries of parlamentary ratifi looker on European astranomy for many Gunnar Malmquist fram Sweden. -

IAU Xxiind General Assembly -The Hague 1994 Editor: SETH SHOSTAK Associate Editor: RENÉ GENEE No

The IAU XXIInd General Assembly -The Hague 1994 Editor: SETH SHOSTAK Associate Editor: RENÉ GENEE No. 1: Tuesday, 16 August he 22nd session of the IAU wide variety of research results, edu- As an easy first excursion, partici- General Assembly will attract cational presentations, and discuss- pants should go to Scheveningen, the nearly two thousand partici- sions of organizational questions such beach community adjacent to The T as naming conventions and other mat- Hague. lt is easily reached by walking pants this year. They will be privy to 23 professional sessions, and can parti- ters of general relevance to IA U three blocks down the Johan de cipate in 14 working groups and joint members. Witlaan to tram 7. The tram trip takes discussions. An impressive, and inti- Needless to say, we also encourage 10 minutes or Jess. midating, total of 600 talks will be those who are visiting The Hague for For those of a more athletic bent, given, and the poster presentations the first time to be sure to avail them- an aggressive walker can be in tally more than a thousand. selves of the many attractions and Scheveningen in 25 minutes- 30 minu- Ali in ail, participants will enjoy a diversions in this cosmpolitan city. tes if your walking style is phlegmatic. Hugo van Woerden, Chairman of the National Organizing Committee, reflects on the history of this he red, white and blue logo for the 22nd General Assembly, year's General Assembly. T used to adorn posters and other official publications (and reproduced above in modest monochrome), was t's a great pleasure to welcome This time, the road stayed open. -

Some Milestones in History of Science About 10,000 Bce, Wolves Were Probably Domesticated

Some Milestones in History of Science About 10,000 bce, wolves were probably domesticated. By 9000 bce, sheep were probably domesticated in the Middle East. About 7000 bce, there was probably an hallucinagenic mushroom, or 'soma,' cult in the Tassili-n- Ajjer Plateau in the Sahara (McKenna 1992:98-137). By 7000 bce, wheat was domesticated in Mesopotamia. The intoxicating effect of leaven on cereal dough and of warm places on sweet fruits and honey was noticed before men could write. By 6500 bce, goats were domesticated. "These herd animals only gradually revealed their full utility-- sheep developing their woolly fleece over time during the Neolithic, and goats and cows awaiting the spread of lactose tolerance among adult humans and the invention of more digestible dairy products like yogurt and cheese" (O'Connell 2002:19). Between 6250 and 5400 bce at Çatal Hüyük, Turkey, maces, weapons used exclusively against human beings, were being assembled. Also, found were baked clay sling balls, likely a shepherd's weapon of choice (O'Connell 2002:25). About 5500 bce, there was a "sudden proliferation of walled communities" (O'Connell 2002:27). About 4800 bce, there is evidence of astronomical calendar stones on the Nabta plateau, near the Sudanese border in Egypt. A parade of six megaliths mark the position where Sirius, the bright 'Morning Star,' would have risen at the spring solstice. Nearby are other aligned megaliths and a stone circle, perhaps from somewhat later. About 4000 bce, horses were being ridden on the Eurasian steppe by the people of the Sredni Stog culture (Anthony et al. -

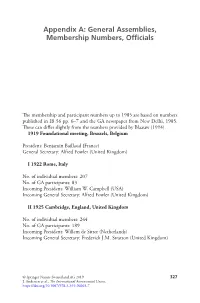

Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials

Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials The membership and participant numbers up to 1985 are based on numbers published in IB 56 pp. 6–7 and the GA newspaper from New Delhi, 1985. These can differ slightly from the numbers provided by Blaauw (1994). 1919 Foundational meeting, Brussels, Belgium President: Benjamin Baillaud (France) General Secretary: Alfred Fowler (United Kingdom) I 1922 Rome, Italy No. of individual members: 207 No. of GA participants: 83 Incoming President: William W. Campbell (USA) Incoming General Secretary: Alfred Fowler (United Kingdom) II 1925 Cambridge, England, United Kingdom No. of individual members: 244 No. of GA participants: 189 Incoming President: Willem de Sitter (Netherlands) Incoming General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 327 J. Andersen et al., The International Astronomical Union, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96965-7 328 Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials III 1928 Leiden, Netherlands No. of individual members: 288 No. of GA participants: 261 Incoming President: Frank W. Dyson (United Kingdom) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) V 1932 Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States No. of individual members: 406 No. of GA participants: 203 Incoming President: Frank Schlesinger (USA) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) V 1935 Paris, France No. of individual members: 496 No. of GA participants: 317 Incoming President: Ernest Esclangon (France) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) VI 1938 Stockholm, Sweden No. of individual members: 554 No. of GA participants: 293 President: Arthur S. Eddington (United Kingdom) until 1944, then Harold Spencer-Jones (United Kingdom) General Secretary: Jan H.