Collaboration and Integration in Performing Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - the Netherlands Tel

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - The Netherlands Tel. + 31 (0)20 556 3000, Fax.+ 31 (0)20 556 3001 Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden The Amsterdam American Hotel is a historic four-star deluxe hotel located in the heart of Amsterdam, at the lively Leidse square. The hotel was built in the year 1900 in Art Deco style, which gives the rooms and the famous Café Americain it’s nostalgic atmosphere. Distance Hotel – Schiphol Airport By car: 24 km – 20 minutes Public transport: Overground tram to Main Railway Station. Direct train to airport – 20 minutes Taxi: EUR 40 – 20 minutes Concert Venues Distance by car or tourbus DeLaMar 0.1 km / 01 min Melkweg 0.2 km / 02 min Paradiso 0.2 km / 02 min Carré 3.0 km / 09 min RAI 3.8 km / 10 min Ziggo Dome 8.6 km / 18 min Facilities & Services Heineken Music Hall 9.5 km / 18 min 175 comfortable hotel rooms Ayoh Rotterdam 76.4 km / 62 min 4 spacious meeting rooms Geldredome 98.5 km / 75 min In-room safe Mini bar Air conditioning 24-hour room service High Speed Wirless Internet Access Coffee and tea making facilities in the room Sauna Fitness Café American , the living room of Amsterdam. In our restaurant you can enjoy small, classic brasserie dishes as well as full-course diner. But you are also welcome for just a coffee or a hearty breakfast in our Café with its typical art nouveau atmosphere. Bar American is a popular hotspot amongst locals and various Making a reservation famous personalities. -

Podia Van De Zeroes: Van 013 Tot Tivolivredenburg De Nieuwbouwgolf Van De Jaren Nul in Beeld

Podia van de Zeroes: van 013 tot TivoliVredenburg De nieuwbouwgolf van de jaren nul in beeld Ingmar Griffioen 14 februari 2014 Zoom De Waerdse Tempel in Heerhugowaard De Zeroes was het tijdperk waarin de drang tot vernieuwing, professionalisering en schaalvergroting in het zalencircuit vorm kreeg in een stoet aan nieuwbouw poppodia. Van Haarlem tot Eindhoven en van Purmerend tot Bergen Op Zoom verrezen nieuwe zalen, vaak ingericht als multifunctionele culturele centra. De nieuwbouwgolf begon grofweg met de opening van 013, Tilburg in 1998 en je zou de opening van TivoliVredenburg (juni) en Doornroosje (oktober) als slotstuk van die dadendrang kunnen zien. 3voor12 kijkt naar de verwachtingen en angsten uit de Zeroes en hoe de vlag er anno 2014 bij hangt. MEGALOMAAN OF GROEISTUIPEN? Najaar 2005 openden twee grote nieuwe zalen in Brabant (Effenaar) en Noord-Holland (Patronaat), twee jaar later zat de nieuwbouwgolf zo'n beetje op haar hoogtepunt. 3voor12 noteerde begin 2007: "Op dit moment zijn meer dan vijftien steden bezig met de her- of nieuwbouw van een poppodium. Bij meer dan tien gaat het om complexen die meer dan duizend bezoekers kunnen huisvesten, vaak verdeeld over meerdere zalen." In dezelfde maand vroeg de Volkskrant zich af wie al die blinkende poptempels toch ging vullen? Internationale boekers constateerden op 3voor12 een tekort aan bands die genoeg publiek trekken. De vraag was kortom: "Verplettert het Nederlandse podiumcircuit zichzelf met megalomane ambities, of beleven we de groeistuipen van een professionaliserende sector?" Zoom Paard van Troje grote zaal na de verbouwing © Nico Laan SLEUTELWOORDEN SCHAALVERGROTING EN PROFESSIONALISERING Belangenvereniging VNPF (Vereniging Nederlandse Poppodia en -Festivals) heeft de stand van zaken in 2008 gevat in Het Grote Poppodium Onderzoek. -

I AMSTERDAM CITY MAP Mét Overzicht Bezienswaardigheden En Ov

I AMSTERDAM CITY MAP mét overzicht bezienswaardigheden en ov nieuwe hemweg westerhoofd nieuwe hemweg Usselincx-haven westerhoofd FOSFAATWEG METHAANWEG haven FOSFAATWEG Usselincx- A 8 Zaandam/Alkmaar D E F G H J K L M N P N 2 4 7 Purmerend/Volendam Q R A B C SPYRIDON LOUISWEG T.T. VASUMWEG 36 34 MS. OSLOFJORDWEG Boven IJ 36 WESTHAVENWEG NDSM-STR. 34 S118 K BUIKSLOOTLAAN Ziekenhuis IJ BANNE Buiksloot HANS MEERUM TERWOGTWEG KLAPROZENWEG D R R E 38 T I JDO J.J. VAN HEEKWEG O O N 2 4 7 Purmerend/Volendam Q KRAANSPOOR L RN S101 COENHAVENWEG S LA S116 STREKKERWEG K A I SCHEPENLAAN N 34 U Buiksloterbreek P B SCHEPENLAAN 36 NOORD 1 36 MT. LINCOLNWEG T.T. VASUMWEG KOPPELINGPAD ABEBE BIKILALAAN N SEXTANTWEG FERRY TO ZAANSTAD & ZAANSE SCHANS PINASSTRAAT H. CLEYNDERTWEG A 1 0 1 PAPIERWEG SPYRIDON LOUISWEG MARIËNDAAL NIEUWE HEMWEG COENHAVENWEG B SPYRIDON LOUISWEG SINGEL M U K METAAL- 52 34 34 MT. ONDINAWEG J Ring BEWERKER-I SPYRIDON LOUISWEG I KS K 38 DECCAWEG LO D J 36 36 MARIFOONWEG I ELZENHAGEN- T L map L DANZIGERKADE MARJOLEINSTR. D E WEG A 37 Boven IJ R R 36 K A RE E 38 SPELDERHOLT VLOTHAVENWEG NDSM-LAAN E 34 N E METHAANWEG K K A M Vlothaven TT. NEVERITAWEG 35 K RADARWEG 36 R Ziekenhuis FOSFAATWEG MS. VAN RIEMSDIJKWEG Stadsdeel 38 H E MARIËNDAALZILVERBERG J 36 C T Noord HANS MEERUM TERWOGTWEG 38 S O Sportcomplex IJDOORNLAAN 34 J.J. VAN HEEKWEG S101 K D L S N A H K BUIKSLOOTLAAN BUIKSLOTERDIJK SPELDERHOLT NSDM-PLEIN I 34 BUIKSLOTERDIJK A Elzenhage KWADRANTWEG M L U MINERVAHAVENWEG SLIJPERWEG J. -

Eileen Standley-Cv2020

EILEEN STANDLEY Clinical Professor – Creative Practices, Movement Practices, and Alexander Technique Curriculum Vitae Tel: 310-406-7488 PO Box 870304 Tempe, AZ 85287-2002 [email protected] http://www.eileenstandley.com EDUCATION Bachelor of Arts Degree Dramatic Art-Dance University California Berkeley (1981) Distinctions: Scholarly Academic Honors Eisner Award in the Performing Art Phi Beta Kappa for Academic Achievement Scholarship Bella Lewitsky Dance Company; USC Idyllwild, CA (1982) Diploma from Media Academie in Hilversum, NL (2002) Fulltime course -Video content editing and theory (AVID, FCP certified) Diploma SAE Technology College in Amsterdam, NL (2000) Full-time Web design and Multimedia Producer program Certified Alexander Technique Teacher AmSAT (2009) Master of Fine Arts in Interdisciplinary Arts: Choreography & Visual Arts; Wilson College, Chambersburg, PA (2017) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS/EMPLOYMENT 2010 to Present Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Film, Dance and Theatre (the School of Music, Dance and Theatre), Clinical Professor (MY) 2009 to 2010 Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Dance Clinical Professor of Creative Practice (one year position) 1986 to 2009 Amsterdam School for the Arts, School for New Dance Development1 Tenured and Guest Artist Faculty positions 1999 to 2009 Amsterdam School for the Arts Guest Artist Faculty in the following departments: 1 The SNDO, School for New Dance Development (School voor Nieuwe Dansontwikkeling in Dutch), is a full time 4- Year professional education course that leads to the diploma Bachelor of Dance – Choreography. Eileen Standley School for New Dance Development, Masters in Choreography Program2, Modern Dance Department, Jazz and Musical Theater Department, National Ballet Department, and Mime (Physical Theater) Department. -

Verzilverpunten Adres Postcode Plaats Telefoon

Bij onderstaande verzilverpunten kan de Theater & Concertbon ingewisseld worden (op volgorde van postcode). Met de Theater en Concertbon kunnen geen online aankopen gedaan worden. VERZILVERPUNTEN ADRES POSTCODE PLAATS TELEFOON WEBSITE PROVINCIE Amsterdams Marionettentheater Nieuwe Jonkerstraat 8 1011 CM AMSTERDAM 020-6208027 www.marionettentheater.nl Noord Holland Het Internationaal Danstheater Kloveniersburgwal 89 1011 KA AMSTERDAM 020-6239112 www.intdanstheater.nl Noord Holland Nationale Opera & Ballet Waterlooplein 22 1011 PG AMSTERDAM 020-6255455 www.hetmuziektheater.nl Noord Holland De Theatercompagnie Kloveniersburgwal 50 1012 CX AMSTERDAM 020-5205320 www.theatercompagnie.nl Noord Holland Betty Asfalt Produkties Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal 282 1012 RC AMSTERDAM 020-6204748 www.bettyasfalt.nl Noord Holland Beurs van Berlage Damrak 243 1012 ZJ AMSTERDAM 020-5304141 www.beursvanberlage.nl/agenda/ Noord Holland Theater Amsterdam Danzigerkade 5 1013 AP AMSTERDAM 020-7055000 www.theateramsterdam.nl Noord Holland Het Veemtheater Van Diemenstraat 410 1013 CR AMSTERDAM 020-6260112 www.hetveemtheater.nl Noord Holland Comedy Cafe IJdok 89 1013 MM AMSTERDAM 020-7220827 www.comedycafe.nl Noord Holland Felix Meritis Keizersgracht 324 1016 EZ AMSTERDAM 020-6231311 www.felix.meritis.nl Noord Holland Boom Chicago Rozengracht 117 1016 LV AMSTERDAM 020-5205320 www.boomchicago.nl Noord Holland Huis aan de Amstel Lauriergracht 99C 1016 RJ AMSTERDAM 020-6229328 www.huisaandeamstel.nl Noord Holland Jeugdtheater de Krakeling Nieuwe Passeerderstraat 1 1016 XP -

Evaluatieverslag 2020 Popronde.Nl

POPRONDE EVALUATIEVERSLAG 2020 POPRONDE.NL 1 Foto cover: Douwe Doorduin - Popronde Poppodium Pre-Party Amsterdam INHOUD INLEIDING POPRONDE 2020 7 1. WERVING EN SELECTIE ACTS 2020 9 2. WAT WEL PLAATSVOND 9 DE COÖRDINATORENDAG IN FEBRUARI 2020 3. HET LAND OP SLOT 13 OVERZICHT EN TOELICHTING PERIODE MAART 2020 - MAART 2021 4. POPRONDE POPPODIUM PRE-PARTIES 19 5. POPRONDE POPPODIUM PRE-PARTIES IN DE MEDIA & EXPOSURE 21 6. POPWAARTS IN DE BASISINFRASTRUCTUUR - BIS 27 7. VOORUITBLIK POPRONDE 2021 EN DAARNA 35 8. BESTUURSVERSLAG EN VERSLAG RAAD VAN TOEZICHT 37 SMOELENBOEK 41 LEMOTAT - Popronde Poppodium Pre-Party Amsterdam 4 5 INLEIDING POPRONDE 2020 Als gevolg van de pandemie heeft er geen Popronde kunnen en mogen plaatsvinden zoals we die gewend waren; in elke stad op (on)denkbare plekken in het centrum optredens van opkomende acts; van intieme singer-songwriter tot knallende noise en energieke indie, van experimentele electronica tot groovende funk, harde hiphop en vrolijke pop. Hordes publiek vrij zappend tussen de locaties; van kapperszaak, tattooshop, ijzerhandel tot kerk, kroeg en club; Voor Stichting Popwaarts was duidelijk, binnen de anderhalve meter samenleving is het vertrouwde Popronde concept niet uitvoerbaar. In maart 2020 ging Nederland – en de rest van de wereld – op slot en nu, een jaar later is het eind daarvan nog niet in zicht. In dit verslag kijken we terug, belichten we wat we wel hebben gedaan, wat goed is gegaan en kijken we vooruit naar de Popronde 2020 inhaaleditie – de Popronde Tiendaagse - eind april / begin mei 2021. Het laatste antwoord op de maatregelen, het uiterste scenario dat we uit de hoge hoed toveren. -

Overzicht VSCD-Podia Met Programmering

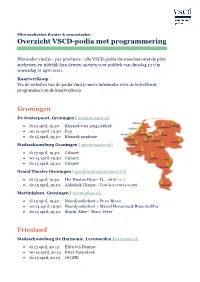

Pilot sneltesten theater & concertzalen Overzicht VSCD-podia met programmering Hieronder vind je - per provincie - alle VSCD-podia die meedoen met de pilot sneltesten en tijdelijk hun deuren openen voor publiek van dinsdag 13 t/m woensdag 21 april 2021. Kaartverkoop Via de websites van de podia vind je meer informatie over de betreffende programma’s en de kaartverkoop. Groningen De Oosterpoort, Groningen | spotgroningen.nl/ • di 13 april, 19.30: Klassiek voor jong publiek • wo 14 april, 19.30: Pop • do 15 april, 19.30: Klassiek symfonie Stadsschouwburg Groningen | spotgroningen.nl/ • di 13 april, 19.30: Cabaret • wo 14 april, 19.30: Cabaret • do 15 april, 19.30: Cabaret Grand Theatre Groningen | grandtheatregroningen.nl/nl • di 13 april, 19.30: Het Houten Huis - ‘Ik… eh ik’ (6+) • do 15 april, 19.30: Abhishek Thapar - ‘Cow is a cow is a cow’ Martiniplaza, Groningen | martiniplaza.nl/ • di 13 april, 19.30: Noordpoolorkest + Pe en Rinus • wo 14 april, 19.30: Noordpoolorkest + Marcel Hensema & Rosa da Silva • do 15 april, 19.30: Stayin' Alive - ‘Disco Fever’ Friesland Stadsschouwburg De Harmonie, Leeuwarden | harmonie.nl/ • di 13 april, 20.15: Ellen ten Damme • wo 14 april, 20.15: Peter Pannekoek • do 15 april, 20.15: OG3NE Overijssel Wilminktheater en Muziekcentrum Enschede | wilminktheater.nl/nl/ • ma 19 april, 19.30: Lente offensief van 5 cabaretiers • di 20 april, 19.30: Lente offensief van 5 cabaretiers • wo 21 april, 19.30: Lente offensief van 5 cabaretiers Zwolse Theaters - Odeon Dommerholtzaal | zwolsetheaters.nl/ • ma 19 april, -

L LP Binnenwerk Tivolivredenburg.Indd

TivoliVredenburg ‘Vijf zalen is ongekend in de wereld en dan zijn ze ook nog gestapeld. Minstens zo uniek is dat TivoliVredenburg gebouwd is door vijf architecten, die elkaar niet de tent uitvochten.’ Op 3 juni 2014 opent Koning muziekpaleis nieuwe Utrechts Willem Alexander met een gongslag het Utrechtse Tivoli- Vredenburg, een muziekpaleis dat zijn weerga niet kent. Van Doorn van H. Herman van foto’s de gerenoveerde Vredenburg- zaal van Herman Hertzberger tot de fonkelnieuwe Ronda popzaal maak je een gang door 35 jaar Utrechtse muziek- geschiedenis. Dit boek kijkt in vijf compleet verschillende zalen, naar de ontstaansgeschiedenis op de historische locatie Vredenburg, de fusie van de gebruikers en de visie van de architecten. TivoliVredenburg Utrechts nieuwe muziekpaleıs nieuwe Utrechts Kom binnen, kom boven. Een hand Colofon Uitgave Deze publicatie van Uitgeverij Lecturis kwam tot maalt een slinger rond over het dak, stand in samenwerking met TivoliVredenburg. Fotografie ons mechaniek begint te lopen – spots Herman H. van Doorn Tekst en interviews Speeldoos zoeken de sterren van de avond op, Ingmar Griffioen Tekeningen vier zalen komen tot leven rond de as, Architectuurstudio hh Gedicht binnenzijde omslag achthoekig, pluche en hout. Luister, ‘Speeldoos’, geschreven in opdracht van TivoliVredenburg, in 2015 opgenomen in: Ingmar Heytze, Utrecht voor beginners en gevorderden, verzamelde Utrechtse gedichten, kijk, drink alles in. Wat krijgt de wereld Uitgeverij Podium, Amsterdam 2015. beter aan het draaien dan muziek? Ontwerp Piet Gerards Ontwerpers (Piet Gerards en Maud van Rossum) Kom verder, nergens ben je dichterbij. Lithografie en druk Vanavond spelen we alleen voor jou. Lecturis, Eindhoven Binden Hexspoor, Boxtel Ingmar Heytze © 2015 Herman H. -

ADE Press Release March 25Th

ADE Confirms 25th Anniversary Edition of its Conference and Festival www.amsterdam-dance-event.nl ADE confirms its 25th anniversary edition in physical form with both conference and festival events set to take place from 13th - 17th October 2021. Additionally, the organisation supports music professionals during the re-opening of the live music industry by making its online B2B platform free-to-access on the road to ADE 2021. The Road to ADE 2021 As a result of the widespread vaccination campaign and rapid test capacity in the Netherlands, ADE expects to celebrate the reopening of its industry at its 25th anniversary edition in Amsterdam taking place from the 13th through 17th of October. The organisation is dedicated to presenting the best possible ADE experience while ensuring public health guidelines, featuring a rich and diverse program for professionals, artists and music enthusiasts alike. The ADE team is thrilled to kick off the road to the ADE Festival 2021 with a varied lineup of organisers announcing their first shows, including Audio Obscura, Awakenings, DGTL, Dockyard, Elrow, Into the Woods, Loveland and Verknipt, as well as venues Concertgebouw, Panama, Melkweg and Paradiso. The latter two have already announced part of their program, with artists including Dave Clarke and Oliver Heldens for Melkweg and Avalon Emerson and Speedy J presents STOOR live for Paradiso set to take the stage. ADE Conference 2021 and free online community Music professionals can gear up for the ADE Pro conference program at Amsterdam's iconic Felix Meritis in October. In addition, the Amsterdam Dance Event Foundation extends its support to the live music industry by inviting music professionals to become an active part of the road to ADE 2021 on its online B2B platform, completely free of charge. -

Media Kit 2017 Farai Shot by Vicky by Shot 08 Issue Farai Subbacultcha Magazine, London Grout in for Subbacultcha

media kit 2017 Farai shot by Vicky by shot 08 Issue Farai Subbacultcha magazine, Grout London in for Subbacultcha We are an independent music platform based in Amsterdam. — We produce progressive shows accompanied by a quarterly music magazine. With the support of a loyal community of members, we have set in place a unique system that enables us to introduce a large and diverse young audience to the emerging music that excites us. Shows Subbacultcha hosts 10+ unruly shows a month, booked in-house and organized by us at venues of our choice. Subbacultcha shows Collaboration and co-hosting We are all about shows. We aim to book and promote unconventional, Besides organizing and producing our own events, we also curate unruly artists at the very start of their careers – right about the time and co-promote shows, festivals and events in collaboration with when they release their first album or tour Europe for the first time. our partners such as Muziekgebouw aan ‘t IJ, Melkweg, Progress Bar, We take cues from independent labels and intertwined networks across Motel Mozaique and many more. the world to unearth the most interesting music-makers out there today. We host shows at our homebase De School, Amsterdam and work closely with small alternative venues in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, organizing Custom events for brands & partners shows where the right audience meets the right artist. We also organize and produce events for brands and partners. Ranging from booking artists and DJs to producing and promoting entire events. Support your Local Area Network Some of the partners we work with are Order, Dr Martens, American Apparel, Urban Outfitters and Goose Island. -

And Erik Alkema

Bildetage presents videos by Avi Krispin and Erik Alkema Bildetage selected the videos of Avi Krispin (IL/NL) and Erik Alkema (NL), whose works reflect on different kinds of possible usage of the medium for the artistic practice. Avi Krispin is always working on a high technical level, many of her works involve several actors, complex lighting and sophisticated recording facilities. Erik approaches video more as a sculptor or a painter. He uses the screen as a frame and a canvas. An extra dimension to expand and to stage the sculptural worlds he creates in his personal and unique textile imagery. Despite a certain sense of humour, what many of the works have in common is a conceptual approach as well as the strategy of expression by assuming a role. Selection of activities of Bildetage (more on www.bildetage.com) Leipzig Discussions and Exhibition: Schöne Kunst, 14.‐16.10.2011 Grosse Kunst, 26.10.2011 Julia Weller: To make it more biutiful, 8.‐10.11.2011 Belgrade Grounded, Gruppenausstellung, KC Grad, 2010 Dreamlike, Gruppenausstellung, Galeria FLU der Akademie der Bildenden Künste, 2010 Rotterdam Left before – right behind, around the corner project space, Rotterdam, Juli 2012. Alpine Gothic: 10.000 Edelweiss, 2011 Georg Oberhumer: What a Stimulating Recreation, Ausstellung, TENT Rotterdam, 2011 Struktura, MAVV, 2011 Fake Identity, Kunst Kamers Rotterdam, 2011 Jasmin Schaitl: Tape‐Loop, Live‐Performance und Video‐Stream, TENT Rotterdam and Kunst&Complex, 2011 Rennes How to pirate an A4. Festival Oodaq d’images poétiques Vienna Corinne -

84 Complete.Pdf

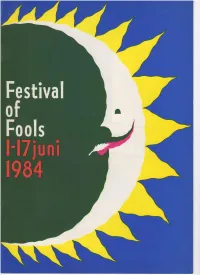

Kaartverkoop Volledig reserveringen programma- toegangsprijzen boekje, prijs: 2,50 Op 21 mei begint de voorverkoop bij de AUB-ticketshop - hoek Leidseplein/Marnixstraat tel.: 22 90 11 Dagelijks van 10.00 - 18.00 uur Alle buitenvoorstellingen zijn gratis Toegangsprijzen voor binnenvoorstellingen varieren van 5,-tot 15,- Tijdens het Festival kan er ook bij de betreffende theaters gereserveerd worden. t fOOLS Opening Slotweekend 16 en 17 juni De officiele opening van het Festival of Fools 1984 De slotmanifestatie van het festival is dit jaar gekon- Tijdens het Festival zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 1 juni om 14.00 uur op sentreerd rond het Leidseplein. Op zaterdag 16 juni goedkope maaltijden de Dam. Op dat moment zal de Wethouder voor de is er's middags op het podium op het Leidseplein en in: Kunstzaken van Amsterdam, mevrouw Luimstra- in het Vondelpark Openluchttheater een uitgebreid Albeda, met een korte toespraak het festival van programma.'s Avonds zijn er een groot aantal voor• Litterair Cafe De Engel- start laten gaan. stellingen en konserten in de Melkweg, Paradiso en bewaarder Op een groot podium treedt daarna de Japanse per- de Balie. Kloveniersburgwal 59 cussiegroep Ondekoza op. Verder zijn te zien: Vince Op zondag 17 is er's middags in het Vondelpark dag. 17.30 - 21.00 uur Bruce, Shusaku & Dormu Dance theatre. Openluchttheater een laatste optreden van Ondeko• za, met daama de Afrikaanse reggaeband Roots Melkweg Anabo. Lijnbaansgracht 234 A Het slotfeest van het Festival of Fools 1984 vindt dag. 18.00 - 21.00 uur dan's avonds plaats in Paradiso met een groots opge- dag. v.a.