1 Rethinking Cultural Diversity: Strategic Communication and Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - the Netherlands Tel

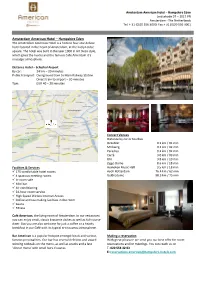

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - The Netherlands Tel. + 31 (0)20 556 3000, Fax.+ 31 (0)20 556 3001 Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden The Amsterdam American Hotel is a historic four-star deluxe hotel located in the heart of Amsterdam, at the lively Leidse square. The hotel was built in the year 1900 in Art Deco style, which gives the rooms and the famous Café Americain it’s nostalgic atmosphere. Distance Hotel – Schiphol Airport By car: 24 km – 20 minutes Public transport: Overground tram to Main Railway Station. Direct train to airport – 20 minutes Taxi: EUR 40 – 20 minutes Concert Venues Distance by car or tourbus DeLaMar 0.1 km / 01 min Melkweg 0.2 km / 02 min Paradiso 0.2 km / 02 min Carré 3.0 km / 09 min RAI 3.8 km / 10 min Ziggo Dome 8.6 km / 18 min Facilities & Services Heineken Music Hall 9.5 km / 18 min 175 comfortable hotel rooms Ayoh Rotterdam 76.4 km / 62 min 4 spacious meeting rooms Geldredome 98.5 km / 75 min In-room safe Mini bar Air conditioning 24-hour room service High Speed Wirless Internet Access Coffee and tea making facilities in the room Sauna Fitness Café American , the living room of Amsterdam. In our restaurant you can enjoy small, classic brasserie dishes as well as full-course diner. But you are also welcome for just a coffee or a hearty breakfast in our Café with its typical art nouveau atmosphere. Bar American is a popular hotspot amongst locals and various Making a reservation famous personalities. -

Waar Flaneren Tot Kunst Verheven Is

Waar flaneren tot kunst verheven is De rol van citybranding bij de herbestemming van Strijp S BART A.M. DE ZWART Marco Polo: “Niemand weet beter dan jij, wijze Kublai, dat je nooit een stad mag verwarren met de woorden die haar beschrijven. En toch is er een verband tussen het een en het ander. Als ik je Olivia beschrijf, een stad rijk aan producten en inkomsten, dan heb ik, om je een idee te geven van haar welvaart, geen ander middel ter beschikking dan te praten over filigraanpaleizen met kussens vol franjes op de vensterbanken van de biforen; achter het hekwerk van een patio besproeien de waterstralen van een draaiende fontein een gazon waar een witte pauw op staat te pronken. Maar uit deze woorden begrijp jij meteen hoe Olivia gehuld is in een smerige roetwolk die zich vasthecht aan de muren van de huizen; dat in het gedrang op straat voetgangers verpletterd worden tegen de muren door manoeuvrerende vrachtwagens. Als ik je moet vertellen over de bedrijvigheid van haar inwoners, praat ik over naar leer geurende werkplaatsen van zadelmakers, over vrouwen die met elkaar kletsen onder het knopen van raffia tapijten, over hangende kanalen waarvan de watervallen molenschoepen in beweging zetten: maar het beeld dat deze woorden oproepen in jouw verlichte bewustzijn is het gebaar waarmee het staal tegen de tanden van de frees gehouden wordt, herhaald door duizenden handen, duizenden malen, op de voor de ploegendienst vastgestelde tijden. Als ik je moet uitleggen hoe de geest van Olivia streeft naar een vrij leven en naar een uiterst verfijnde beschaving, zal ik je vertellen van dames die ’s nachts zingend in verlichte kano’s varen tussen de oevers van een groene vijver; maar dat is slechts om je eraan te herinneren dat er in de buitenwijken waar iedere avond mannen en vrouwen uit boten stappen als rijen slaapwandelaars, altijd wel iemand is die in het donker in lachen uitbarst, die zich te buiten gaat aan grappen en sarcastische opmerkingen. -

Pleidooi Voor Een Integraal, Inclusief Muziekbeleid, Is Een Uitgave Van De Raad Voor Cultuur

De balans, de behoefte Pleidooi voor een integraal, inclusief muziekbeleid Voorwoord 4 Muziek in dialoog 6 Hoofdaanbevelingen 7 1. Naar een integrale, inclusieve visie op muziek 8 Sectoradvisering 8 Een integrale blik 8 De rol van de overheid 11 Muziek in relatie tot andere domeinen 12 2. Het muzikale ecosysteem 14 Inleiding 14 Kunstenaars en producerende instellingen 15 Presentatieplekken: podia en festivals 28 Digitale distributie 30 Talentontwikkeling 31 Kunstvakonderwijs 32 Ondersteunende instellingen 35 Tot slot 37 3. De muzieksector vanuit artistiek perspectief 41 Artistieke ontwikkelingen in productie en presentatie 41 Talentontwikkeling 48 De creatie van nieuwe muziek 50 Documentatie en ontsluiting 50 Aanbevelingen 54 4. De muzieksector vanuit maatschappelijk perspectief 58 Iedereen is een luisteraar 58 Publieksmarkt en toegankelijkheid 59 Muziekeducatie en -participatie 61 Aanbevelingen 66 5. De muzieksector vanuit economisch perspectief 70 Financieringsstromen vanuit de overheid 70 Private financieringsstromen 79 6. Hoofdaanbevelingen 91 Ontwikkel een integraal, inclusief muziekbeleid 91 Besteed meer aandacht aan essentiële functies 92 Erken de kenmerken en kracht van een regionaal muziekklimaat 93 Herbezie de samenstelling van de culturele basisinfrastructuur 94 Besteed expliciet aandacht aan diversiteit 95 Besteed expliciet aandacht aan de arbeidsmarkt voor muziekprofessionals 96 Tot slot 97 Bijlagen 99 Adviesaanvraag 100 Lijst van gesprekspartners 111 Literatuur 116 Colofon 122 Sectoradviezen / Muziek / Inleiding / Voorwoord Voorwoord Muziek in Nederland, waar hebben we het dan over? De muzieksector is groot en Nederlandse artiesten en ensembles brengen samen een lange, gevarieerde speellijst in praktijk. Op een willekeurige dag tijdens het opstellen van dit advies klinken tegelijkertijd Janáčeks ‘Ave Maria’ door Cappella Amsterdam en ‘Nobody’s Wife’ van Anouk over de radio (respectievelijk op NPO Radio 4 en 2). -

Kernpodia 2020

Kernpodia 2020 Naam Podium Plaats Catergorie Link website 013 Tilburg A www.013.nl Altstadt Eindhoven C www.altstadt.nl Baroeg Rotterdam C www.baroeg.nl Beest Goes B www.tbeest.nl Bibelot Dordrecht C www.bibelot.net Boerderij Zoetermeer A www.cultuurpodiumboerderij.nl Bolwerk Sneek B www.hetbolwerk.nl Bosuil Weert A www.debosuil.nl Burgerweeshuis Deventer A www.burgerweeshuis.nl Cacaofabriek Helmond B www.cacaofabriek.nl Corneel Lelystad B www.corneel.nl De Helling Utrecht C www.dehelling.nl Doornroosje Nijmegen B www.doornroosje.nl Dru Cultuurfabriek Ulft B www.drucultuurfabriek.nl Effenaar Eindhoven B www.effenaar.nl Ekko Utrecht C www.ekko.nl Fluor Amersfoort B www.fluor033.nl Flux Zaandam C www.podiumdeflux.nl Gebouw-T Bergen op Zoom A www.gebouw-t.nl Gebr. De Nobel Leiden A www.gebrdenobel.nl Gigant Apeldoorn B www.gigant.nl Grenswerk Venlo B www.grenswerk.nl Groene Engel Oss B www.groene-engel.nl Hall Of Fame Tilburg C www.hall-fame.nl Hedon Zwolle A www.hedon-zwolle.nl Het Podium Hoogeveen C www.hetpodium.nl Iduna Drachten B www.iduna.nu Kroepoekfabriek Vlaardingen C www.kroepoekfabriek.nl Luxor Live Arnhem A www.luxorlive.nl Manifesto Hoorn C www.manifesto-hoorn.nl Meester Almere C www.demeesteralmere.nl Melkweg Amsterdam C www.melkweg.nl Merleyn Nijmegen C www.merleyn.nl Metropool Hengelo C www.metropool.nl Mezz Breda A www.mezz.nl Muziekcafé Helmond C www.muziekcafehelmond.nl Neushoorn Leeuwarden C www.neushoorn.nl Nieuwe Nor Heerlen B www.nieuwenor.nl Nirwana Lierop C www.nirwana.nl OCCII Amsterdam C www.occii.org P3 Purmerend -

Podia Van De Zeroes: Van 013 Tot Tivolivredenburg De Nieuwbouwgolf Van De Jaren Nul in Beeld

Podia van de Zeroes: van 013 tot TivoliVredenburg De nieuwbouwgolf van de jaren nul in beeld Ingmar Griffioen 14 februari 2014 Zoom De Waerdse Tempel in Heerhugowaard De Zeroes was het tijdperk waarin de drang tot vernieuwing, professionalisering en schaalvergroting in het zalencircuit vorm kreeg in een stoet aan nieuwbouw poppodia. Van Haarlem tot Eindhoven en van Purmerend tot Bergen Op Zoom verrezen nieuwe zalen, vaak ingericht als multifunctionele culturele centra. De nieuwbouwgolf begon grofweg met de opening van 013, Tilburg in 1998 en je zou de opening van TivoliVredenburg (juni) en Doornroosje (oktober) als slotstuk van die dadendrang kunnen zien. 3voor12 kijkt naar de verwachtingen en angsten uit de Zeroes en hoe de vlag er anno 2014 bij hangt. MEGALOMAAN OF GROEISTUIPEN? Najaar 2005 openden twee grote nieuwe zalen in Brabant (Effenaar) en Noord-Holland (Patronaat), twee jaar later zat de nieuwbouwgolf zo'n beetje op haar hoogtepunt. 3voor12 noteerde begin 2007: "Op dit moment zijn meer dan vijftien steden bezig met de her- of nieuwbouw van een poppodium. Bij meer dan tien gaat het om complexen die meer dan duizend bezoekers kunnen huisvesten, vaak verdeeld over meerdere zalen." In dezelfde maand vroeg de Volkskrant zich af wie al die blinkende poptempels toch ging vullen? Internationale boekers constateerden op 3voor12 een tekort aan bands die genoeg publiek trekken. De vraag was kortom: "Verplettert het Nederlandse podiumcircuit zichzelf met megalomane ambities, of beleven we de groeistuipen van een professionaliserende sector?" Zoom Paard van Troje grote zaal na de verbouwing © Nico Laan SLEUTELWOORDEN SCHAALVERGROTING EN PROFESSIONALISERING Belangenvereniging VNPF (Vereniging Nederlandse Poppodia en -Festivals) heeft de stand van zaken in 2008 gevat in Het Grote Poppodium Onderzoek. -

Jaarplan2019.Pdf

1 VOORWOORD 3 2 PROGRAMMA 5 2.1 Klassiek 5 2.2 Nieuw gecomponeerde muziek 7 2.3 Jazz 9 2.4 Pop en dance 11 2.5 Wereldmuziek 13 2.6 Educatie en participatie 15 2.7 Kennis & Debat 16 2.8 Zakelijke verhuur 16 3 PUBLIEK 17 3.1 Bereik 17 3.2 Inclusiviteit 18 3.3 Nationale en internationale bekendheid en waardering 18 3.4 Hospitality 19 3.5 Klantenservice en informatie 20 4 PAND 21 4.1 In ons gebouw 21 4.2 Rondom ons gebouw 22 5 PARTNERS 23 5.1 TivoliVredenburg Fonds 23 5.2 Sponsoring 23 5.3 Fondsen 24 5.4 Samenwerking in de stad en regio 24 6 BEDRIJFSVOERING 26 6.1 Personeel en organisatie 26 6.2 Kwaliteit en rendement 28 7 BEGROTING 30 7.1 Activiteiten 30 7.2 Bezoekers 31 7.3 Winst en verliesrekening 2019 33 Roisin Murphy 30 augustus 2018 • Ronda © Ben Houdijk 2 1. VOORWOORD Met het eerste seizoen-aanbod hoopt het Muziekcentrum het publiek […] duidelijk te maken dat de programmering een ópen gegeven is, open voor invulling, open voor suggesties, open voor ontwikkeling. - Mathieu Heinrichs, Muziekcentrum Vredenburg: ontmoetingsplaats voor mensen en muziek. Bron: catalogus ter gelegenheid van de opening van Muziekcentrum Vredenburg, 1979. 2019 is een feestjaar. We hebben twee jubilea te vieren. De Grote Zaal bestaat veertig jaar en onze jonge organisatie TivoliVredenburg beleeft haar eerste lustrum. Op 26 januari 1979 opende Muziekcentrum Vredenburg zijn deuren. Vijf jaar geleden, op 3 juli 2014, werd TivoliVredenburg feestelijk geopend in aanwezigheid van koning Willem-Alexander. -

Ik Ben Ilse Hoeflaak, Kom Uit Santpoort En Woon Al 10 Jaar in Haarlem En Ken Veel Leuke Plekjes Daar

Ik ben Ilse Hoeflaak, kom uit Santpoort en woon al 10 jaar in Haarlem en ken veel leuke plekjes daar. Zelf hou ik van reizen, cultuur, zon, zee, strand, lezen, sporten, muziek en dansen. Van zonnen op het strand, leren surfen, borrelen op het terras of een concert zien bij Woodstock of in het magische openluchttheater Caprera midden in het bos! Hieronder mijn hoogtepunten van Haarlem en omstreken: Activiteiten - Mooi weer: wijnproeverij met Chateau78 door de grachten van Haarlem, zonnen bij strandtent Woodstock, concert in openluchttheater Caprera of een biertje bij het kampvuur bij stadsstrand de Oerkap. - Slecht weer: Bikram yoga, naar cultfilm in de Toneelschuur en winkelen in Haarlem en Amsterdam. Winkel-Tip! Snuffel eens rond bij de Kleine Houtstraat en de Schachelstraat in Haarlem. Onder andere aparte boetiekjes, conceptstores, antiek-, woon- en kledingwinkels (surf en vintage) als Number Nine, Revert & ID. Voor 2ehands meubeltjes Stijlloods, Rataplan Haarlem en Vintagestore Hoofddorp. Koffie en Lunch Wolkers, Dodici (beste koffie), Blender, de Overkant, Staal (streekproducten en lezen), Spaarne 66 en op het terras bij restaurant Zuiddam aan het mooie Spaarne. Restaurants Ora (biologisch, Italiaans eten met binnentuin), Dodici (kleine gerechtjes en goede wijn), Klein Centraal (wat luxer in de buurt van camping, ook terras), Het Goede Uur (kaasfondue in authentieke setting), Truffels (luxer), Bruxelles (gezellig eetcafé), Erawan (Thais) en Indiacorner (Indiaas). Vooral in de Lange Veerstraat die doorgaat in de Kleine Houtstraat zijn heel veel leuke restaurantjes te vinden. Verder zit er in Overveen STACH met de lekkerste hamburgers en biologische maaltijden om mee te nemen. Borrelen - Buiten: Brasserie van Beinum, stadstrand de Oerkap, het Veerkwartier (aan het meer), restaurant Zuiddam. -

Brf VNPF "De Waarde Van POP"

http://www.vnpf.nl/media/files/de-waarde-van-pop.pdf De maatschappelijke DE betekenis van popmuziek WAA R D E VA N POP DE WAARDE VAN POP 1 Popcultuur gaat verder dan alleen popmuziek. Het is een innovatieve cultuur die deel uitmaakt van en terug te vinden is in film, theater, games, grafische vormgeving, andere muziek stromingen, e-cultuur, beeldende kunst, dans en literatuur. Popmuziek is sterk verbonden met jeugdcultuur en vormt een verbindend element tussen andere kunst- en cultuuruitingen. Popcultuur is op allerlei manieren verweven in de samenleving en draagt een belangrijke maatschappelijke waarde in zich op het gebied van cultuur, participatie, talentontwikkeling en economie. Voor pop geldt net zo goed als voor sport dat er zonder 2 DE WAARDE VAN POP DE WAARDE VAN POP 3 brede basis en zonder circuit geen mogelijk heid is tot excelleren en het verzilveren van die maatschappelijke waarden. Popcultuur heeft raakvlakken met beleidsterreinen als cultuur, ruimtelijke ordening, economie, citymarketing, toerisme, welzijn, jeugd, onderwijs en integratie. Het versterken van die brede basis, de infrastructuur van popmuziek, is daarom een belangrijke taak van gemeenten. De podiumkunsten en ook de popsector staan door het huidige overheidsbeleid onder forse druk. Met De waarde van pop tonen initiatiefnemers POPnl en de Vereniging Nederlandse Poppodia en Festivals (VNPF) hoe popcultuur tot uiting komt, welke maatschappelijke waarde zij vertegenwoordigt en hoe belangrijk het is om te blijven investeren in popcultuur. De waarde van pop wordt de Nederlandse gemeenten aangeboden zodat zij zich kunnen versterken met een aantrekkelijk, duurzaam en onderscheidend popcultureel ondernemersklimaat. Optreden The Vagary in de Melkweg, Amsterdam Foto: Richard Tas 4 DE WAARDE VAN POP DE WAARDE VAN POP 5 Het bereik van pop Van alle Dit bereik is het meest zichtbaar in de digitale verspreiding van de muziek, de verkoop van cultuuruitingen geluidsdragers en de bezoekersaantallen van heeft popmuziek het concerten. -

Astria Suparak Is an Independent Curator and Artist Based in Oakland, California. Her Cross

Astria Suparak is an independent curator and artist based in Oakland, California. Her cross- disciplinary projects often address urgent political issues and have been widely acclaimed for their high-level concepts made accessible through a popular culture lens. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art institutions and festivals across ten countries, including The Liverpool Biennial, MoMA PS1, Museo Rufino Tamayo, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, Carnegie Mellon, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, sports bars, and rock clubs. Her current research interests include sci-fi, diasporas, food histories, and linguistics. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (selected) . Independent Curator, 1999 – 2006, 2014 – Present Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art, film, music, and academic institutions and festivals across 10 countries, as well as for unconventional spaces like roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, elementary schools, sports bars, and rock clubs. • ART SPACES, BIENNIALS, FAIRS (selected): The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, Eyebeam, Participant Inc., Smack Mellon, New York; The Liverpool Biennial 2004, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), England; Museo Rufino Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; FotoFest Biennial 2004, Houston; Space 1026, Vox Populi, Philadelphia; National -

NERG 1958 Deel 23 Nr. 02

Tijdschrift van het Nederlands Radiogenootschap DEEL 23 No. 2 1958 De overdracht van omroepprogramma’s via het interlokale telefoonnet door D. van den Berg *) Voordracht gehouden voor het Nederlands Radiogenootschap op 25-4-'57. Summary* For the programme transmission over the Netherlands wire-broadcasting network much use is made of trunk cables. The author describes the various types of programme circuits and the additional repeaters and branching amplifiers. Furthermore he explains what networks are required for the afore-said transmission, what demands they have to meet, and how the networks are maintained. 1. Internationale aanbevelingen voor muziektransmissie. Het telefoonnet en met name het moderne telecommunicatienet leent er zich uitermate goed voor om muziekprogramma's over te brengen, of ruimer geformuleerd: programma's die aan de telefoonfrequentieband van 300-3400 Hz niet voldoende hebben, kunnen op zeer behoorlijke wijze langs kabelverbindingen worden overgebracht. De Union Internationale des Télécommunications (U.I.T.) die als één van zijn onderdelen heeft het Comité Consultatif Inter national Téléfonique (CCIF) dat onlangs zijn naam een iets ge wijzigde vorm heeft gegeven waarbij de telecommunicatie als zodanig wordt genoemd, (CCITT) heeft indertijd een aanbeve ling uitgegeven, welke in zekere zin curieus is en aan de andere kant voldoende aanknoping geeft om het onderwerp te intro duceren. *) Centrale Directie PTT 38 D. van den Berg De aanhef van deze aanbeveling is aardig genoeg om volledig weer te geven: „Le Comité -

Te Goed Om Te Falen

Te goed om te falen Dankwoord van voorzitter raad van toezicht Lennart van der Meulen bij het vertrek van Frans Vreeke als directeur van TivoliVredenburg op donderdag 5 juli 2018. ‘Trots? Mwaaah. Ik vind trots sowieso een moeilijk woord. Moeilijk begrip, trots. Nogmaals ik heb met dat begrip een beetje moeite.’ Aan het woord is Frans Vreeke en we lopen op het eind van de podcast Krenten uit de Pap als de directeur van TivoliVredenburg voor het eerst een beetje stilvalt tegen podcastpresentator en oud-zanger van de band John Coffey, David Achter de Molen. Ze hebben het dan drie kwartier gehad over haast vijf roerige jaren TivoliVredenburg. Over hoe megagroot de klus was. ‘Zoveel groter dan ik ooit gedaan had.’, volgens Frans Vreeke. Over de argwaan bij de start, al het gemopper en gegalbak, en de omslag in de waardering bij iedereen die daadwerkelijk kennismaakte met het gebouw. De mannen hebben het over het legendarische openingsconcert waarbij de Ronda explodeerde en het hele MT dronken werd van geluk en de vele biertjes om dat geluk weg te spoelen. Over de shit van de eerste twee jaar toen de financiering niet op orde was. De opluchting toen de commissie Gehrels - in de woorden van Frans Vreeke zelf - constateerde: ‘Jezus Christus wat hebben jullie een fantastische prestatie geleverd in de oorlog die je zo’n beetje moest voeren’. En over de overwinningsroes toen de gemeenteraad midden in de nacht van 30 juni 2016 het advies van Gehrels overnam en TivoliVredenburg de financiële en bestuurlijke ruimte kreeg om los te gaan. Er komen nieuwe bandjes langs in het gesprek en legendarische optredens. -

I AMSTERDAM CITY MAP Mét Overzicht Bezienswaardigheden En Ov

I AMSTERDAM CITY MAP mét overzicht bezienswaardigheden en ov nieuwe hemweg westerhoofd nieuwe hemweg Usselincx-haven westerhoofd FOSFAATWEG METHAANWEG haven FOSFAATWEG Usselincx- A 8 Zaandam/Alkmaar D E F G H J K L M N P N 2 4 7 Purmerend/Volendam Q R A B C SPYRIDON LOUISWEG T.T. VASUMWEG 36 34 MS. OSLOFJORDWEG Boven IJ 36 WESTHAVENWEG NDSM-STR. 34 S118 K BUIKSLOOTLAAN Ziekenhuis IJ BANNE Buiksloot HANS MEERUM TERWOGTWEG KLAPROZENWEG D R R E 38 T I JDO J.J. VAN HEEKWEG O O N 2 4 7 Purmerend/Volendam Q KRAANSPOOR L RN S101 COENHAVENWEG S LA S116 STREKKERWEG K A I SCHEPENLAAN N 34 U Buiksloterbreek P B SCHEPENLAAN 36 NOORD 1 36 MT. LINCOLNWEG T.T. VASUMWEG KOPPELINGPAD ABEBE BIKILALAAN N SEXTANTWEG FERRY TO ZAANSTAD & ZAANSE SCHANS PINASSTRAAT H. CLEYNDERTWEG A 1 0 1 PAPIERWEG SPYRIDON LOUISWEG MARIËNDAAL NIEUWE HEMWEG COENHAVENWEG B SPYRIDON LOUISWEG SINGEL M U K METAAL- 52 34 34 MT. ONDINAWEG J Ring BEWERKER-I SPYRIDON LOUISWEG I KS K 38 DECCAWEG LO D J 36 36 MARIFOONWEG I ELZENHAGEN- T L map L DANZIGERKADE MARJOLEINSTR. D E WEG A 37 Boven IJ R R 36 K A RE E 38 SPELDERHOLT VLOTHAVENWEG NDSM-LAAN E 34 N E METHAANWEG K K A M Vlothaven TT. NEVERITAWEG 35 K RADARWEG 36 R Ziekenhuis FOSFAATWEG MS. VAN RIEMSDIJKWEG Stadsdeel 38 H E MARIËNDAALZILVERBERG J 36 C T Noord HANS MEERUM TERWOGTWEG 38 S O Sportcomplex IJDOORNLAAN 34 J.J. VAN HEEKWEG S101 K D L S N A H K BUIKSLOOTLAAN BUIKSLOTERDIJK SPELDERHOLT NSDM-PLEIN I 34 BUIKSLOTERDIJK A Elzenhage KWADRANTWEG M L U MINERVAHAVENWEG SLIJPERWEG J.