Ethics, Human Rights and Development in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

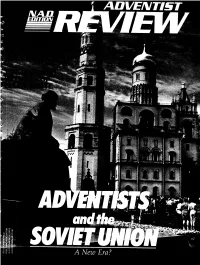

ADVENTIST REVIEW, the First Issue of Each Month, Hidden Sorrow and Loneliness

ADVENTIST N.A.D EDITION A New Era? LETTERS ti Hands Up is the responsibility of the hostess. It consecrated and talented workers would seem presumptuous for should enter the city and set to work I'd like to raise my hands (that's 4 right, both of them) and say "Praise guests to use appliances or equip- (Evangelism, p. 34), and that large the Lord" for the two hands-on ment without a request or an invita- corps of workers be organized to editorials in the March 26 REVIEW. tion, which would make it unneces- work the city (Medical Ministry, pp. They were the most thought-pro- sary to remind them of the 299-301). Where are they expected voking material in the issue. Hands household rules. to live? The van people are not Having pleasant and tactful con- working the city from outside but down. DENNIS FERREE Rohrersville, Maryland trol of one's home should never be from inside, where they are coming construed as coercion. to know the pain, hurt, language, Alone in Church NELLIE ONDRIZEK and culture of city folk. Coalmont, Tennessee Local churches were conducting Thank you for "Married, in a feeding program from their base- Church, and Alone" (Mar. 12). I Wiser? ments before the van ministry. married my Pentecostal (inactive) The March 5 REVIEW announced Grand Concourse, a church in the husband in 1984 and was baptized Glendale Adventist Medical Cen- Bronx, started that program in 1981, into the SDA family a year ago. ter's decision to be involved in in and still feeds 150 persons every While I miss him when he doesn't vitro fertilization, artificial insemi- Tuesday. -

Lind, Magdalon Eugen (1910–1985) and Kezia (1909–2013)

Magdalon and Kezia Lind Photo courtesy of Leif Lind. Lind, Magdalon Eugen (1910–1985) and Kezia (1909–2013) YONA BALYAGE, AND NATHANIEL MUMBERE WALEMBA Yona Balyage, Ph.D. in education (Central Luzon State University, Philippines), is a professor in Educational Administration and Management. He serves as director of Quality Assurance at the University of Eastern Africa, Baraton, Eldoret, Kenya. He has also served as department head and school dean at the same university. He is married to Eseza and they have three children. Nathaniel Mumbere Walemba, D.Min. (Andrews University, Berrien Spring, Michigan U.S.A.), retired in 2015 as executive secretary of the East-Central Africa Division (ECD) of Seventh-day Adventists. In retirement, he is assistant editor of this encyclopedia for ECD. A Ugandan by birth, Walemba has served the Seventh-day Adventist Church in many capacities having started as a teacher, a frontline pastor, and principal of Bugema Adventist College in Uganda. He has authored several magazine articles and a chapter, “The Experience of Salvation and Spiritualistic Manifestations,” in Kwabena Donkor, ed.The Church, Culture and Spirits (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 2011), pp. 133-143. He is married to Ruth Kugonza and they have six children and fourteen grandchildren. Referred to as “God’s Angel to Mount Rwenzori,” Magdalon Eugen (M. E.) Lind, along with his wife Kezia, were pioneer missionaries of the Seventh-day Adventist Church to the Rwenzori1 Mountains2 in western Uganda. He was a pastor, director, president, fluent speaker of several African languages, fundraiser, and a generous donor. As missionaries, Magadalon and Kezia were beloved by the people of Uganda and other countries where he worked, including3 Kenya, United Kingdom, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Lebanon.4 Early Life M. -

An Approach to a Holistic Ministry in a Seventh-Day Adventist Urban Church in Uganda

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1988 An Approach to a Holistic Ministry in a Seventh-day Adventist Urban Church in Uganda Nathaniel Mumbere Walemba Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Walemba, Nathaniel Mumbere, "An Approach to a Holistic Ministry in a Seventh-day Adventist Urban Church in Uganda" (1988). Dissertation Projects DMin. 241. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/241 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

88-317 ANNUAL COUNCIL Nairobi, Kenya, October 4-11, 1988

88-317 ANNUAL COUNCIL Nairobi, Kenya, October 4-11, 1988 GENERAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE October 4, 1988, 7 p.m. PRESENT J 0 Achilihu, Elvin Adams, C 0 Adeogun, C E Aeschlimann, Ebenezer Agboka, J Agboka, G Agoki, N F Aina, G H Akers, A A Alalade, Artur Alfredo, G Amayo, Erich Amelung, K Ruselinyange Amon, K 0 Amoyaw, W T Andrews, Bogale Anulo, R E Appenzeller, S A Armah, W John Arthur, P K Asareh, Z F Ayonga, D 0 Babalola, G P Babcock, Phenias Bahimba, Karl H Bahr, R P Bailey, Stefano Baraburiye, M T Battle, B B Beach, M A Bediako, Mikael Beesoo, S I Biraro, Bekele Biri, Jack Bohannon, Ebow Bonnie, F A Botomani, J T Bradfield, C E Bradford, Ellen Bresee, W Floyd Bresee, V L Bretsch, C D Brooks, G W Brown, Reinder Bruinsma, Shirley Burton, W B Buruchara, Ireno Cargill, E E Carman, G Tom Carter, R H Carter, D W B Chalale, S Chand, Dimas Chende, S H Chileya II, C S J Chinyowa, G J Christo, W T Clark, Paul Clare, W 0 Coe, G F Colon, Daniel Cordas, Antonio Coroa, G H Crumley, Vasco Cubenda, H Carl Currie, R L Dale, L T Daniel, P B de Freitas, D D Dennis, P M Diaz, J M Dube, H D Dumba, 0 C Edwards, G Egwakhe, G Elieneza, Jean Ema'a, S A Farag, E C Fehlberg, J H Figueroa, Karen Flowers, Philip Follett, Z N S Fosi, Anacleto Franco, R I Gainer, D F Gilbert, R J Gombwa, 0 E Gordon, Gordon Gray, I E Grice, Daniel Gueho, L M Guttschuss, G Gordon Hadley, Robert Hall, K R Heinrich, C D Henri, Lloyd Henry, Bekele Heye, D I Isabirye, B E Jacobs, R L Joachim, S B Johansen, W G Johnsson, Bruce Johnston, F L Jones, R K Kamundi, H B Kanjewe, D W Kapitao, A -

State Building and Service Provision After Rebel Victory in Civil Wars

From Insurgent to Incumbent: State Building and Service Provision After Rebel Victory in Civil Wars The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40050154 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA From Insurgent to Incumbent: State Building and Service Provision after Rebel Victory in Civil Wars A dissertation presented by Kai Massey Thaler to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2018 © 2018 – Kai Massey Thaler All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Kai Massey Thaler Professor Steven Levitsky From Insurgent to Incumbent: State Building and Service Provision after Rebel Victory in Civil Wars ABSTRACT How do rebel organizations govern when they gain control of an internationally recognized state? I advance an organization-level theory, arguing that ideology affects recruitment, socialization of fighters and followers, and group relations with civilians, creating path dependencies that carry over to shape post-victory state building and governance. I code rebel groups on a spectrum between two ideal types: programmatic and opportunistic. More programmatic organizations’ aims extend beyond power to socioeconomic and political transformation, spurring attempts to expand state reach over and through territory and society. -

From the End of the World to the Ends of the Earth

edition afem? mission specials 1 Stefan Höschele This book offers a readable access to Adventist missiology, not only describing it but showing how it developed, thereby turning its eyes away from the end of the world to the ends of the earth. Those who want to know how 3500Adventists grew to 12 million, will find some answers here. FromFrom the the End End Prof. Dr. Klaus Fiedler University of Malawi ofof the the World World STEFAN HÖSCHELE, born 1972. Studied at Friedensau University, 1991-1996. Served the Seventh-day Adventist Church as a missionary in Algeria, 1993-1994, and as a toto the the Ends Ends lecturer of theology at Tanzania Adventist College, 1997- 2003. Since 2003, he is a lecturer of Systematic Theology at Friedensau University. Currently writes a doctoral disser- tation at the University of Malawi about the history of ofof the the Earth Earth Adventism in Tanzania. He is married and has 3 children. The Development of ISBN 3-937965-14-9 Seventh-Day-Adventist Missiology Foreword by Klaus Fiedler VTR edition afem • mission specials 1 Höschele • Adventist Missiology edition afem? mission specials 1 Note on the Web Version This web version of the book From the End of the World to the Ends of the Earth: The Development of Seventh-Day Adventist Missiology is made available to the public in electronic format for research and private use only. Therefore, it is not public domain, and the publisher (Verlag für Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, Nürnberg, Germany) owns the full copyright. It may not be posted on any web site or stored on servers. -

Uganda, Country Information

Uganda, Country Information UGANDA ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURE HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS PROMINENT PEOPLE GLOSSARY REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended for use by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Uganda.htm[10/21/2014 10:09:59 AM] Uganda, Country Information 2. -

Review and Herald. Publishing Association 55 West

Nonprofit Organization REVIEW AND HERALD. PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION U.S. Postage 55 WEST OAK RIDGE DRIVE PAID HAGERSTOWN, MD 21740 Hagerstown, MD Permit No. 261 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED [DITORIAL The Road Map to Success n the journey of life everyone would cultivate the habit of regular Bible study. like to arrive at the destination called Another idea is to attempt to identify "success." In the King James Version of with the characters of the Bible. Put the Bible, Joshua 1:8 contains the only yourself in the middle of the verses and occurrence of the word success to be found paragraphs and stories. Let God speak to in that entire version of the Bible. you personally and prayerfully. The words of our text provide us with Look for promises from God to claim "If the believer the road map that leads to success: "This as you read. Look for commands to obey. book of the law shall not depart out of thy Look for examples to follow. And look for would be a mouth; but thou shalt meditate therein the failures of others that can serve as winner in the day and night, that thou mayest observe warnings to you. to do according to all that is written therein: for then thou shalt make thy way he Bible not only tells us about our game of life, prosperous, and then thou shalt have Savior but invites us to trust Him and he/she is not good success." T to receive Him. Indeed it is the Bible that shows us the will of our Lord for us. -

MAKERERE SUPPLEMENT SHORT.Indd

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAKERERE UNIVERSITY we build for the future we build for the future 3 2 3 cated all this by awarding him the Secretariat. A Uganda, born He was a leading national- ment. In his book (Not Yet devotedly served as chancellor for Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) of 44 years ago, Eriyo has since ist and political agitator in the Uhuru), Mzee Jaramogi Odinga Makerere University as well. Makerere University. PRO Ritah April 2012 been Deputy EAC independence struggle for Nyasa- reveals that he did his A’levels at Secretary General in charge of land which became Malawi after Alliance High School after which Namisango says they were recog- JULIUS NYERERE nizing his outstanding record of Productive and Social Sectors. independence. Born on Novem- he went to Makerere University excellence in diplomacy, journal- She has a Bachelors degree in ber 22 1929, Murray William in 1940. Thereafter he returned Julius Kambarage Nyerere ism, administration, governance; Social Sciences, a Post Graduate Kanyama Chiume, a Makerere to Kenya to teach at a second- was born on April 13th 1922 and BUILDING regional and global politics. Diploma in Education (PGDE) graduate was synonymous ary school- Maseno High School died on October 14th 1999. The and a Master’s degree in arts-all with the Malawi independence until 1948 when he joined Kenya Tanzanian founding president was from Makerere University. A struggle of the 1950s-1960s. He African Union (KAU), one of an alumnus of Makerere Univer- RICHARD SEZIBERA proud Makererean, Jessica Eriyo was also one of the leaders of the the political parties then fighting sity. -

Review and Herald for 1990

„nvENTIsr NAD EDITION Editor s page 3 • Guide to Indianapolis page 6 • Theme Song page 12 • Delegates page 15 The enclosed booklet, "Global Mission: Person to Person," will explain this global To Catch a Vision strategy and how you can be involved. Read it carefully; pray as you read. Ask the Lord: How do You want me to be involved? And Neal C. Wilson when He answers you, as He surely will, President, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists respond "Here am I, Lord; send me." Indianapolis is a fine and gracious city. It is large enough to be a city but small enough elcome to the fifty-fifth cession of the mitment to our Lord as a result of what hap- to be friendly. As I have visited here over the WGeneral Conference of Seventh-day pens in Indianapolis. past 25 years I have found the people to be Adventists! "Grace be unto you, and peace, My report to the world church, which I polite and cultured. I have also been im- from God our Father, and from the Lord Jesus present on the opening evening of the session pressed by the genuine spirit of devotion and Christ" (1 Cor. 1:3). and which usually appears in the bulletins, Christian love of our fellow believers in the Delegates, friends, visitors, we have gath- takes a different form this time. We have Indiana Conference. I feel confident that you ered in Indianapolis from almost every nation prepared a video that gives highlights from who are delegates and visitors will enjoy your under heaven. -

AIDS and International Seventh-Day Adventism

"IS THIS OUR CONCERN?" AIDS and International Seventh-day Adventism. Ronald Lawson Professor Department of Urban Studies Queens College, CUNY Flushing, NY 11367 A paper read at the meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, Pittsburgh, August 1992 The Problem Summers were a time of fear during the polio crisis of the 1950s--but Seventh-day Adventists were at the forefront of treating the disease. Indeed, their work so impressed a prominent Ohio family that they donated a 400-bed hospital in suburban Dayton to the church.1 Why were Adventists so prominent in this respect? Adventist theology emphasizes "wholeness", linking physical wellness, spiritual health and evangelism. These concerns led the Adventist Church to establish a major system of hospitals and clinics around the world, to advocate natural remedies and foster a vegetarian diet. The involvement of the church in the medical field has led members to enter medically- related occupations in disproportionate numbers. The early Adventist interest in water treatments prepared them well to treat polio victims. Given this history, it is not unreasonable to expect that the Adventist church would once again take a prominent place in responding to AIDS, the new epidemic which struck in the 1980s. Not only did the Adventist concern with health, medicine, and public health and its widespread hospital system prepare it ideally to confront an international epidemic, but rapid growth of the church in Africa, the continent most ravaged by the disease,2 and the new Adventist self-description as "the Caring Church" would seem to have demanded action. However, in the words of Bekele Heye, President of the Eastern Africa Division of the world church, "AIDS is not an Adventist issue!" [interview, 1990].