Asymmetric Warfare: Bangladesh Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Bangladesh

Annexure 3 Plan to Create Greater Bangla Desh including Assam in it Greater Bangladesh From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Greater Bangladesh (translated variously as Bengali : , Brihat Bangladesh ;[1] Bengali : Brihad Bangladesh ;[2] Bengali : , Maha Bangladesh ;[3] and Bengali : , Bishal Bangla [4] ) is a political theory circulated by a number of Indian politicians and writers that People's Republic of Bangladesh is trying for the territorial expansion to include the Indian states of West Bengal , Assam and others in northeastern India. [5] The theory is principally based on fact that a large number of Bangladeshi illegal immigrants reside in Indian territory. [6] Contents [hide ] 1 History o 1.1 United Bengal o 1.2 Militant organizations 2 Illegal immigration o 2.1 Lebensraum theory o 2.2 Nellie massacre o 2.3 The Sinha Report 3 References [edit ]History The ethno-linguistic region of Bengal encompasses the territory of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal , as well as parts of Assam and Tripura . During the rule of the Hindu Sena dynasty in Bengal the notion of a Greater Bangladesh first emerged with the idea of uniting Bengali-speaking people in the areas now known as Orissa , Bihar and Indian North East (Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya ) along with the Bengal .[7] These areas formed the Bengal Presidency , a province of British India formed in 1765, though Assam including Meghalaya and Sylhet District was severed from the Presidency in 1874, which became the Province of Assam together with Lushai Hills in 1912. This province was partitioned in 1947 into Hindu -majority West Bengal and Muslim - majority East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to facilitate the creation of the separate Muslim state of Pakistan , of which East Bengal became a province. -

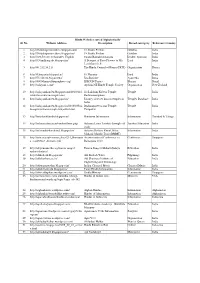

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Fazlul Huq and Bengal Politics in the Years Before the Second Partition of Bengal (1947)

6 Fazlul Huq and Bengal Politics in the years before the Second Partition of Bengal (1947) On 24 April 1943, H.E. the Governor Sir John Herbert with the concurrence of the Viceroy, issued a proclamation by which he revoked the provision of Section 93 and invited the leader of the Muslim League Assembly Party, Khwaja Sir Nazimuddin to form a new ministry. The aspirant Nazimuddin who made constant effort to collect support in order to form a new ministry, ultimately managed to have the support of 140 members in the Bengal Assembly (consisting of 250 membrs). On the other hand, the Opposition (led by Fazlul Huq) had 108 members. Following the dismissal of the Second Huq Ministry, a large number of Muslim M.L.A.s thought it expedient to cross the floor and join the League because of Governor‟s inclination towards Nazimuddin whom he invited to form a new ministry. As they flocked towards the League, the strength of the League Parliamentary Party rose from 40 to 79. Abul Mansur Ahmed, an eminent journalist of those times, narrated this trend in Muslim politics in his own fashion that „everyone had formed the impression that the political character of the Muslim Legislators was such that whoever formed a ministry the majority would join him‟1 which could be applicable to many of the Hindu members of the House as well. Nazimuddin got full support of the European Group consisting of 25 members in the Assembly. Besides, he had been able to win the confidence of the Anglo-Indians and a section of the Scheduled Caste and a few other members of the Assembly. -

Women's Awakening in Bengal in the Swadeshi Era

© July 2021| IJIRT | Volume 8 Issue 2 | ISSN: 2349-6002 Women's Awakening in Bengal in the Swadeshi era Nilendu Biswas Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, Asannagar Madan Mohan Tarkalankar College, Nadia,West Bengal, India Abstract - As women have been seen in various covered with Swadeshi consciousness. By joining a revolutionary activities in colonial Bengal, the large number of women, men were indirectly able to awakening of women has been reflected in these gain strength and courage. Due to the inconsistency of activities. As a poisonous consequence of the British rule, the information, it is difficult to gather proper the British government implemented the 'Partition of historical evidence of various activities of women's Bengal' to break the backbone of the Bengali nation. But in this incident, the Bengali nation, Hindus and Muslims awakening. Because, in that era, the activities of alike, erupted in protest, outraged by the British women wrapped in the atmosphere of conservatism government's conspiracy. Breaking the traditional idea were not made public. As a result, women's activities of Bengali women in the ‘Andor mohal’ (inner palace), could not be illuminated by the light of the larger the women came out in the ‘Bahir mohal’ (outer palace) external world outside of society, remaining in the and joined the Swadeshi movement covered with secluded corners of the inner court. While Swadeshi consciousness. By joining a large number of acknowledging this obstacle, we can highlight the women, men were indirectly able to gain strength and awakening of women in the light of the information courage. While acknowledging this obstacle, we can mentioned in various papers. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

Wbadmi Project Impact Assessment Report- Phase 2

2020 WBADMI PROJECT IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT- PHASE 2 INTERNATIONAL WATER MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 7 Contributors ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 8 1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................... 14 2. STUDY FRAMEWORK ..................................................................................................................... 18 2.1 Objective of the Study .......................................................................................................... 18 2.2 Methodological Framework ................................................................................................. -

Matua’ Society

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 6 June 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 FOLKLORE AND SOCIAL BELIEFS IN ‘MATUA’ SOCIETY Nilendu Biswas, Assistant Professor, Department of History Asannagar Madan Mohan Tarkalankar College, Nadia,West Bengal, India Abstract: The Matua religion occupies a special place in the study of the history of the lower classes of India. The social customs and practices of the Matuas, which are located in the lower echelons of Hinduism, have perpetuated their culture. Through their marriage system and shraddha rituals, the prevailing folklore even provoked protests against the Brahmin society. Harichand Tagore has a special role in the social and cultural life of the Matuas. The Matuas originated from the lower class or lower class of the Hindus, so there are many similarities with the Hindus in terms of their social folklore. Although they are located at the lowest level of society, their existence has survived in the course of time. The internal rituals and customs of contemporary society have influenced the Matuas. The Matuars themselves have continued the movement to assert their position in the social sphere. My main objective in this research paper is to establish the status of the Matuas as an independent nation by highlighting folklore and social beliefs. Key words: Namahsudra - social exploitation - Matua - Harichand - women - folklore. Introduction: The Matua movement was a special trend in the study of the history of the lower classes in India. In the then East Bengal of undivided India, the Namashudra community was at the very bottom of the lower caste Hindus, they had no social status, no rights. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. No. Reference Broad catergory Website Address Description Country 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/m Hindu Kush odern/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temp Hindu Temples of Kabul les_of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?modul Hindu Temples of Afaganistan e=pluspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint &title=Hindu%20Temples%20in%20Afg hanistan%20.html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Bangladesh Assessment

BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 – 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 – 2.6 III HISTORY Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 3.1 – 3.4 1972-1982 3.5 – 3.8 1983 – 1990 3.9 – 3.15 1991 – 1996 3.16 – 3.21 1997 - 1999 3.22 – 3.32 January 2000 - October 2000 3.33 – 3.35 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Constitution 4.1.1 – 4.1.3 Government 4.1.4 President 4.1.5 – 4.1.6 Parliament 4.1.7 – 4.1.9 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM 4.2.1 – 4.2.6 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.2 1974 Special Powers Act 4.3.3 – 4.3.5 Public Safety Act 4.3.6 – 4.3.8 2 V HUMAN RIGHTS 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.3 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Torture 5.2.1 – 5.2.2 Police 5.2.3 – 5.2.9 Supervision of Elections 5.2.10 – 5.2.12 Human Rights Groups 5.2.13 – 5.2.15 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities 5.3.1 – 5.3.6 Biharis 5.3.7 – 5.3.10 Chakmas 5.3.11 – 5.3.12 Rohingyas 5.3.13– 5.3.16 Ahmadis 5.3.17 – 5.3.18 Women 5.3.19 – 5.3.31 Children 5.3.32 - 5.3.37 5.4 OTHER ISSUES Assembly and Association 5.4.1 – 5.4.3 Speech and Press 5.4.4 – 5.4.7 Travel 5.4.8 Chittagong Hill Tracts 5.4.9 – 5.4.13 Student Organizations 5.4.14 – 5.4.16 Taslima Nasreen 5.4.17 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 5.4.18 Domestic Servants 5.4.19-5.4.20 Prison Conditions 5.4.21 -5.2.22 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY 3 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. -

Annual Administrative Report for 2008-2009

Annual Administrative Report for 2008-2009 FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL 1 CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Preface 1 2. Introduction 2 3. REVENUE BRANCH 4 (i) Directorate of Commercial Taxes 6–12 (ii) Directorate of Agricultural Income Tax 13–15 (iii) Directorate of Electricity Duty 16–18 (iv) Directorate of Registration and Stamp Revenue 19–31 (v) Directorate of State Lottery 32–34 (vi) Directorate of Entry Taxes / Revenue Intelligence 35–36 (vii) Policy Planning Unit 37–38 (viii) WB Commercial Taxes Appellate & Revisional Board 39–40 (ix) Bureau of Investigation 41–43 (x) West Bengal Taxation Tribunal 44–45 (xi) West Bengal Settlement Commission 46 (xii) Office of the Collectorate of Stamps Revenue, Kolkata 47–48 (xiii) Right to Information Cell 49–50 4. BUDGET BRANCH 51–74 (i) Project Monitoring Unit 70 (ii) Statistics Cell 71 (iii) RIDF Cell 72 (iv) Data Processing Centre 73–74 5. AUDIT BRANCH 75–97 (i) Directorate of Treasuries & Accounts, W.B 77–79 (ii) Directorate of Pension, Provident Fund & Group Insurance, W.B. 80–88 (iii) Assistance to Political Sufferers (APS) Branch 89 (iv) Directorate of Small Savings 90–91 (v) Economic Offences Investigation Cell 92–94 (vi) Secretariat A/Cs 95–96 (vii) Medical Cell 97 6. INSTITUTIONAL FINANCE 98–106 (i) West Bengal Financial Corporation 98–103 (ii) West Bengal Infrastructure Development Finance Corporation 104–106 7. AUTONOMOUS BODIES 107–110 (i) Public Service Commission, West Bengal 107–108 (ii) State Administrative Tribunal, West Bengal 109–110 8. INTERNAL AUDIT BRANCH 111–117 9. LAW CELL 118–127 10. -

Bangladesh, Country Information

Bangladesh, Country Information BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS: VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RUGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY General file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Bangladesh.htm[10/21/2014 9:57:04 AM] Bangladesh, Country Information 2.1 Located in south Asia, the People's Republic of Bangladesh is bordered almost entirely by India, except for a small frontier in the Southeast with Burma and the coastline along the Bay of Bengal in the south.