Draupadi" by Mahasveta Devi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to BI-Tagavad-Gita

TEAcI-tER'S GuidE TO INTROduCTioN TO BI-tAGAVAd-GiTA (DAModAR CLASS) INTROduCTioN TO BHAqAVAd-qiTA Compiled by: Tapasvini devi dasi Hare Krishna Sunday School Program is sponsored by: ISKCON Foundation Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 1. History ofthe Kuru Dynasty 3 2. Birth ofthe Pandavas 10 3. The Pandavas Move to Hastinapura 16 4. Indraprastha 22 5. Life in Exile 29 6. Preparing for Battle 34 7. Quiz 41 Crossword Puzzle Answer Key 45 Worksheets 46 9ntroduction "Introduction to Bhagavad Gita" is a session that deals with the history ofthe Pandavas. It is not meant to be a study ofthe Mahabharat. That could be studied for an entire year or more. This booklet is limited to the important events which led up to the battle ofKurlLkshetra. We speak often in our classes ofKrishna and the Bhagavad Gita and the Battle ofKurukshetra. But for the new student, or student llnfamiliar with the history ofthe Pandavas, these topics don't have much significance ifthey fail to understand the reasons behind the Bhagavad Gita being spoken (on a battlefield, yet!). This session will provide the background needed for children to go on to explore the teachulgs ofBhagavad Gita. You may have a classroonl filled with childrel1 who know these events well. Or you may have a class who has never heard ofthe Pandavas. You will likely have some ofeach. The way you teach your class should be determined from what the children already know. Students familiar with Mahabharat can absorb many more details and adventures. Young children and children new to the subject should learn the basics well. -

Understanding Draupadi As a Paragon of Gender and Resistance

start page: 477 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 477–492 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a22 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Understanding Draupadi as a paragon of gender and resistance Motswapong, Pulane Elizabeth University of Botswana [email protected] Abstract In this article Draupadi will be presented not only as an unsung heroine in the Hindu epic Mahabharata but also as a paragon of gender and resistance in the wake of the injustices meted out on her. It is her ability to overcome adversity in a venerable manner that sets her apart from other women. As a result Draupadi becomes the most complex and controversial female character in the Hindu literature. On the one hand she could be womanly, compassionate and generous and on the other, she could wreak havoc on those who wronged her. She was never ready to compromise on either her rights as a daughter-in-law or even on the rights of the Pandavas, and remained ever ready to fight back or avenge with high handedness any injustices meted out to her. She can be termed a pioneer of feminism. The subversion theory will be employed to further the argument of the article. This article, will further illustrate how Draupadi in the midst of suffering managed to overcome the predicaments she faced and continue to strive where most women would have given up. Key words Draupadi; marriage; gender and resistance; Mahabharata and women 1. Introduction The heroine Draupadi had many names: she was called Draupadi from her father’s family; Krishnaa the dusky princess, Yajnaseni-born of sacrificial fire, Parshati from her grandfather side, panchali from her country; Sairindhiri, the maid servant of the queen Vitara, Panchami (having five husbands)and Nitayauvani,(the every young) (Kahlon 2011:533). -

Dharma As a Consequentialism the Threat of Hridayananda Das Goswami’S Consequentialist Moral Philosophy to ISKCON’S Spiritual Identity

Dharma as a Consequentialism The threat of Hridayananda das Goswami’s consequentialist moral philosophy to ISKCON’s spiritual identity. Krishna-kirti das 3/24/2014 This paper shows that Hridayananda Das Goswami’s recent statements that question the validity of certain narrations in authorized Vedic scriptures, and which have been accepted by Srila Prabhupada and other acharyas, arise from a moral philosophy called consequentialism. In a 2005 paper titled “Vaisnava Moral Theology and Homosexuality,” Maharaja explains his conception consequentialist moral reasoning in detail. His application of it results in a total repudiation of Srila Prabhupada’s authority, a repudiation of several acharyas in ISKCON’s parampara, and an increase in the numbers of devotees whose Krishna consciousness depends on the repudiation of these acharyas’ authority. A non- consequentialist defense of Śrīla Prabhupāda is presented along with recommendations for resolving the existential threat Maharaja’s moral reasoning poses to the spiritual well-being of ISKCON’s members, the integrity of ISKCON itself, and the authenticity of Srila Prabhupada’s spiritual legacy. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Dharma as a Consequentialism ..................................................................................................................... 1 Maharaja’s application of consequentialism to Krishna Consciousness ..................................................... -

Greater Bangladesh

Annexure 3 Plan to Create Greater Bangla Desh including Assam in it Greater Bangladesh From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Greater Bangladesh (translated variously as Bengali : , Brihat Bangladesh ;[1] Bengali : Brihad Bangladesh ;[2] Bengali : , Maha Bangladesh ;[3] and Bengali : , Bishal Bangla [4] ) is a political theory circulated by a number of Indian politicians and writers that People's Republic of Bangladesh is trying for the territorial expansion to include the Indian states of West Bengal , Assam and others in northeastern India. [5] The theory is principally based on fact that a large number of Bangladeshi illegal immigrants reside in Indian territory. [6] Contents [hide ] 1 History o 1.1 United Bengal o 1.2 Militant organizations 2 Illegal immigration o 2.1 Lebensraum theory o 2.2 Nellie massacre o 2.3 The Sinha Report 3 References [edit ]History The ethno-linguistic region of Bengal encompasses the territory of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal , as well as parts of Assam and Tripura . During the rule of the Hindu Sena dynasty in Bengal the notion of a Greater Bangladesh first emerged with the idea of uniting Bengali-speaking people in the areas now known as Orissa , Bihar and Indian North East (Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya ) along with the Bengal .[7] These areas formed the Bengal Presidency , a province of British India formed in 1765, though Assam including Meghalaya and Sylhet District was severed from the Presidency in 1874, which became the Province of Assam together with Lushai Hills in 1912. This province was partitioned in 1947 into Hindu -majority West Bengal and Muslim - majority East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to facilitate the creation of the separate Muslim state of Pakistan , of which East Bengal became a province. -

UCLA Historical Journal

The Ambiguity of the Historical Position of Hindu Women in India: Sita, Draupadi and the Laws of Manu Sangeeta R. Gupta ^^^^'^ HE CURRENT' SUBORDINATE POSITION of Indian women in social, m legal and cultural realms is claimed by fundamentalists to be based on Jim Hindu tradition and supported by religious scriptures. Centuries-old gender roles' for women are depicted as Hindu traditions which need to be protected. Those contesting these views are condemned as attacking Hinduism itself. This article will examine the historical and scriptural basis, if any, of these submissive female gender roles and vvall provide arguments against their current traditional interpretation. While these roles do have historical roots in the Hindu culture, the scriptural "validation" is a political and social tool used by funda- mentalist forces through the ages to justify and perpetuate the oppression of Hindu women. I wall further argue that the religious scriptures themselves are open to several interpretations, but only those that perpetuate the patriarchal^ concept of the "ideal" Hindu woman have been espoused by the majority of the Brahamanical class. This article will deconstruct female gender roles through a careful examination of specific characters in the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharatha, to illustrate an alternate and perhaps more complete picture of the position of women. The Laws of Manu,^ which are frequently quoted by fundamentalists, brahmin priests and others to justify the submissive role ofwomen as "natural," will also be examined to present a more comprehen- sive picture. Religious and cultural norms in India are interwoven and, as such, have a tremendous impact on the daily lives' of both women and men. -

2455-3921 the Festival of Draupadi in Vanniyar Community V.Kathiravan

Volume: 2; No: 1; March-2016. pp 92-97. ISSN: 2455-3921 The Festival of Draupadi In Vanniyar Community V.Kathiravan Assistant Professor in History, VHNSN College (Autonomous), Virudhunagar, India. *Corresponding Author Email Id: [email protected] Festivals are mingle with human life and given entire satisfaction of their life without fair and festival on one country, village or community will exist. Fair and festivals of the particular district, town, and village usually express their entire life style. People from all walks of life are longing to celebrate their fair and festivals. The Hindus, Christians, Muslims and other religious sects also mingled with their own fair and festivals. The Vanniyars also very much involved and observed their fair and festivals in a grand manner. Family Deities and Festivals of the Vanniyars The annual festivals of the Vanniyars were celebrated in a befitting manner. They worshiped Draupathi as a head of the Vanniya goddesses. Also, in dramatic plays, the king was always taken by a Kshatriya, who is generally a Vanniya. These peculiarities, however, have become common nowadays, when privileges peculiar to one caste are being trenched upon by the other caste men. In the Tirupporur temple, the practice of beating the Mazhu (red hot iron) is done by a dancing – girl serving the Vanniya caste. The privilege of treading on the fire is also peculiar to the Vanniyas. In South Arcot district, “Draupadi’s temples are very numerous, and the priest at them is generally a Palli by caste, and Pallis take the leading part in the ceremonies. Why this should be so is not clear. -

Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sita, Draupadi, Gandhari

Education 2014, 4(5): 122-125 DOI: 10.5923/j.edu.20140405.03 Sita (Character from the Indian epic –Ramayana), Draupadi and Gandhari (Characters from another Indian epic – Mahabharata) - A Comparative Study among Three Major Mythological Female Characters - Gandhari: An exception- Uditi Das1,*, Shamsad Begum Chowdhury1, Meejanur Rahman Miju2 1Institute of Education, Research and Training, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh 2Institute of Education, Research and Training (IERT), University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstract There are lots of female characters in Mahabharata and Ramayana but few characters enchant people of all ages and all classes. Mass people admit that Sita should be the icon of all women. Draupadi though a graceful character yet not to be imitated. Comparatively, Gandhari’s entrance into the epic is for a short while; though her appearance is very negligible, yet our research work is to show logically that Gandhari among these three characters is greater than the greatest. We think and have wanted to prove that Gandhari with her short appearance in the epic, excels all other female characters- depicted in Mahabharata and Ramayana. Keywords Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sita, Draupadi, Gandhari eighteen chapters. Again these chapters have been divided 1 . Introduction into one hundred sub-chapters. There are one lac (hundred thousand) verses in Mahabharata. Pandu, Kunti, Draupadi Ramayana: Ramayana is an epic composed by Valmiki and her five husbands, Dhritarastra, Gandhari and their one based on the life history of Ram-the king of the then Oudh hundred tyrannic sons – all are some of the famous and and is divided into seven cantos (Kanda). Sita was Ram’s notorious characters from this great epic. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Justice in the Hands of Torture

Justice “In the Hands of Torture” Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Justice “in the hands of Torture” Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Narayanashrama Tapovanam Venginissery, P.O. Ammadam Thrissur, Kerala 680 563, INDIA www.swamibhoomanandatirtha.org 2 Justice “In the Hands of Torture” Author: Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Published by © Managing Trustee Narayanashrama Tapovanam Venginissery, P.O. Ammadam Thrissur, Kerala 680 563, INDIA Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.swamibhoomanandatirtha.org eBook Reprint June 2013 All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. 3 This book is a compilation of a series of articles by Poojya Swamiji, that appeared in the Monthly Journal Vicharasethu – The Path of Introspection. This series began in the June 1975 issue and concluded in the September 1975 issue. Here the articles have been presented as they were in the original se- ries and no further editing has been carried out. 4 JUSTICE “IN THE HANDS OF TORTURE” In the April issue, under the title 'Dear Souls become humans first' I was speaking about the Grandfather Bheeshma, his greatness, the masterly, though amazing, way in which he spoke and conducted himself in the battlefield, even in the most crucial and life- surrendering situations. In connection with the trend of that thought, my mind began to ponder over the behaviour of the same elderly Knower on an earlier occasion when Draupadi was sub- jected to inhuman torture by Duhshasana in the open assembly of the Kurus, right in front of her husbands, the Pandava brothers. -

Wintersemester 2017/18

des Instituts für Südasien-, Tibet- und Buddhismuskunde Wintersemester 2017/18 1 2 Lehrveranstaltungen am ISTB Überblick LV-Nr. LV-Typ ECTS SSt. LV-Leiter Titel Seite 140345 PS 5 2 Angermeier, Vitus Wie man ein Königreich führt - Streifzüge durch das Arthaśāstra 5 140344 VO 5 2 Buß, Johanna Einführung in die moderne Südasienkunde 6 140307 UE 5 2 Buß, Johanna Moderne Geschichte Nepals 7 140280 VO+UE 10 4 Chudal, Alaka Einführung in die Nepali I 7 140366 UE 5 2 Chudal, Alaka Begleitende Übung zur Einführung in die Nepali I 7 140171 UE 5 2 Chudal, Alaka Hindi-Grammatik für Fortgeschrittene 8 140079 UE 5 2 Chudal, Alaka Leichte Hindi-Lektüre 8 140103 UE 5 2 Chudal, Alaka Women in the Nepali Press 9 140362 SE 7 2 Dannecker, Petra Migration und Entwicklung in Südasien 9 140115 UE 5 2 David, Hans-Jürgen Kultur und Religion des westlichen Himalaya 10 140089 UE 5 2 Dolensky, Jan Begleitende Übung zur Einführung in das klassische Tibetisch I 36 An Introduction to Hindu Tantrism: History, Rituals and 140241 VO 5 2 Ferrante, Marco 10 Philosophy 140091 VO 5 2 Freschi, Elisa Einführung in die Indologie 12 Kolloquium zu den Philosophien und Religionen Südasiens für 140126 KO 5 2 Freschi, Elisa 13 fortgeschrittene Studierende 140246 PS 5 2 Gaenszle, Martin Ethnische Bewegungen in Südasien 14 140181 UE 5 2 Gaenszle, Martin Indigene Historiographien in Nepal 15 140185 SE 10 2 Gaenszle, Martin Orale Traditionen in Indien und Nepal 16 Masterkonversatorium Kultur und Gesellschaft des modernen 140186 KO 5 2 Gaenszle, Martin 17 Südasien 140078 VO+UE 10 4 Geisler, -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

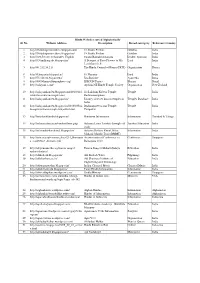

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Fazlul Huq and Bengal Politics in the Years Before the Second Partition of Bengal (1947)

6 Fazlul Huq and Bengal Politics in the years before the Second Partition of Bengal (1947) On 24 April 1943, H.E. the Governor Sir John Herbert with the concurrence of the Viceroy, issued a proclamation by which he revoked the provision of Section 93 and invited the leader of the Muslim League Assembly Party, Khwaja Sir Nazimuddin to form a new ministry. The aspirant Nazimuddin who made constant effort to collect support in order to form a new ministry, ultimately managed to have the support of 140 members in the Bengal Assembly (consisting of 250 membrs). On the other hand, the Opposition (led by Fazlul Huq) had 108 members. Following the dismissal of the Second Huq Ministry, a large number of Muslim M.L.A.s thought it expedient to cross the floor and join the League because of Governor‟s inclination towards Nazimuddin whom he invited to form a new ministry. As they flocked towards the League, the strength of the League Parliamentary Party rose from 40 to 79. Abul Mansur Ahmed, an eminent journalist of those times, narrated this trend in Muslim politics in his own fashion that „everyone had formed the impression that the political character of the Muslim Legislators was such that whoever formed a ministry the majority would join him‟1 which could be applicable to many of the Hindu members of the House as well. Nazimuddin got full support of the European Group consisting of 25 members in the Assembly. Besides, he had been able to win the confidence of the Anglo-Indians and a section of the Scheduled Caste and a few other members of the Assembly.