E. Mervyn Taylor's Prints on Maori Subjects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Cultural Impact Assessment, May 2007

Supplemental Cultural Impact Assessment for the Proposed Advanced Technology Solar Telescope (ATST) at Haleakalā High Altitude Observatories Papa‘anui Ahupua‘a, Makawao District, Island of Maui TMK: (2) 2-2-07:008 Prepared for KC Environmental and The National Science Foundation (NSF) Prepared by Colleen Dagan, B.S. Robert Hill B.A. Tanya L. Lee-Greig, M.A. and Hallett H. Hammatt, Ph.D. Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc. Wailuku, Hawai‘i (Job Code: HALEA 2) May 2007 O‘ahu Office Maui Office Kailua, Hawai‘i 96734 16 S. Market Street, Suite 2N Ph.: (808) 262-9972 www.culturalsurveys.com Wailuku, Hawai‘i 96793 Fax: (808) 262-4950 Ph: (808) 242-9882 Fax: (808) 244-1994 Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HALEA 2 Management Summary Management Summary Report Reference Supplemental Cultural Impact Assessment for the Proposed Advanced Technology Solar Telescope (ATST) at Haleakalā High Altitude Observatories Papa‘anui Ahupua‘a, Makawao District, Island of Maui TMK: (2) 2-2-07:008 (Dagan et al. 2007) Date May 2007 Project Number CSH Job Code: HALEA 2 Project Location Overall Location: Pu‘u Kolekole, Haleakalā High Altitude Observatories (TMK [2] 2-2-07:008), as depicted on the USGS 7.5 minute Topographic Survey Map, Portions of Kilohana Quadrangle and Lualailua Hills Quadrangle. Preferred ATST Site Location: Mees Solar Observatory Facility Alternate ATST Site Location: Reber Circle Land Jurisdiction State of Hawai‘i Agencies National Science Foundation (NSF) – Proposing Agency Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) – Proposing Agency University of Hawai‘i Institute for Astronomy (UH IfA) – Managing Agency U.S. -

Art's Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki

Art’s Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki This is the text of an illustrated paper presented at ‘Art History's History in Australia and New Zealand’, a joint symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Art History in the University of Melbourne and the Australian and New Zealand Association of Art Historians (AAANZ), held on 28 – 29 August 2010. Responding to a set of questions framed around the ‘state of art history in New Zealand’, this paper reviews the ‘invention’ of a nationalist art history and argues that there can be no coherent, integrated history of art in New Zealand that does not encompass the timeframe of the cultural production of New Zealand’s indigenous Māori, or that of the Pacific nations for which the country is a regional hub, or the burgeoning cultural diversity of an emerging Asia-Pacific nation. On 10 July 2010 I participated in a panel discussion ‘on the state of New Zealand art history.’ This timely event had been initiated by Tina Barton, director of the Adam Art Gallery in the University of Victoria, Wellington, who chaired the discussion among the twelve invited panellists. The host university’s department of art history and art gallery and the University of Canterbury’s art history programme were represented, as were the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the City Gallery, Wellington, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries. The University of Auckland’s department of art history1 and the University of Otago’s art history programme were unrepresented, unfortunately, but it is likely that key scholars had been targeted and were unable to attend. -

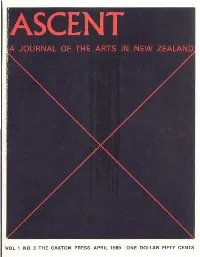

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

Legacy – the All Blacks

LEGACY WHAT THE ALL BLACKS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE BUSINESS OF LIFE LEGACY 15 LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP JAMES KERR Constable • London Constable & Robinson Ltd 55-56 Russell Square London WC1B 4HP www.constablerobinson.com First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2013 Copyright © James Kerr, 2013 Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologise for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition. The right of James Kerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-47210-353-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-47210-490-8 (ebook) Printed and bound in the UK 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Cover design: www.aesopagency.com The Challenge When the opposition line up against the New Zealand national rugby team – the All Blacks – they face the haka, the highly ritualized challenge thrown down by one group of warriors to another. -

Embodied Pedagogy: Examples of Moral Practice from Art Education

EMBODIED PEDAGOGY: EXAMPLES OF MORAL PRACTICE FROM ART EDUCATION Ruth Boyask University of Canterbury, New Zealand Educators operate today in a climate that favours instrumental means to achieve economically rational ends. This emphasis conflicts with the moral purpose of education, which is concerned ostensibly with widening participation and increasing personal liberty. Framed by this potential conflict is an investigation into the activity of historical figures in New Zealand art education to reveal how their deliberate activities negotiated the dominant discourses of their times, and how they shifted cultural production and understandings towards divergent social ends. These historical cases provide insight into possibilities for contemporary educators. Teaching and learning occur both within and outside of educational institutions, policies and sectors. Whilst this premise may not appear particularly innovative or surprising, taken seriously it has the potential to destabilise existing orders of educational practice. It indicates that the creation of knowledge as it is experienced does not necessarily conform to generalised policies nor does it occur within the formal institutions and educational sectors that we have constructed for its legitimation and continuance. However, this premise conflicts with basic assumptions operating currently within the discipline of education, where educational knowledge is positioned in relation to specific and discrete epistemological constructions. This article is developed from a fundamentally phenomenological position, whereby social discourses are constructed through embodied interaction and dialogue, resulting in social practices such as pedagogy, which are ritualised and re-enacted throughout our institutions. The discussion claims that pedagogies have moral implications in that they expand or inhibit social participation and personal liberty, and therefore they encourage educators, when determining a course of action, to deliberate on how their practices intersect with educational structures. -

A Case Study of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Maori Stereotypes, Governmental Poiicies and Maori Art in Museums Today: A Case Study of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Rohana Crelinsten A Thesis in The Department of Art Education Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 1999 O Rohana Crelinsten, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 dcanaâa du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Weiiing(ori OttawaON KlAON4 OnawaON K1AW Canada Canade The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dlowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Maori Stereotypes, Governmental Policies and Maori Art in Museums Today: A Case Study of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tcngarewa Rohana Crelinsten Maori art in New Zealand museums has a Long history extending back to the first contacts made between Maori (New Zealand's Native peoples) aud Europeans. -

BULLETIN of the CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TE PUNA O WAIWHETU Summer December 03 – February 04

BULLETIN OF THE CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TE PUNA O WAIWHETU summer december 03 – february 04 Open 10am – 5pm daily, late night every Wednesday until 9pm Cnr Worcester Boulevard & Montreal Street, PO Box 2626 Christchurch, New Zealand Tel: (+64 3) 941 7300, Fax: (+64 3) 941 7301 Email: [email protected] www.christchurchartgallery.org.nz Gallery Shop tel: (+64 3) 941 7388 Form Gallery tel: (+64 3) 377 1211 Alchemy Café & Wine Bar tel: (+64 3) 941 7311 Education Booking Line tel: (+64 3) 941 8101 Art Gallery Carpark tel: (+64 3) 941 7350 Friends of the Christchurch Art Gallery tel: (+64 3) 941 7356 b.135 Exhibitions Programme Bulletin Editor: Sarah Pepperle Gallery Contributors 2 Introduction ISLANDS IN THE SUN MAKING TRACKS COMING SOON! Director: Tony Preston A few words from the Director Curator (Contemporary): Felicity Milburn 31 OCTOBER – 1 FEBRUARY 04 13 FEBRUARY – 30 MAY SILICA, SHADOW Curatorial Assistant (Contemporary): Jennifer Hay AND LIGHT Curatorial Assistant (Historical): Ken Hall 3 My Favourite A remarkable collection of prints A unique installation by Canterbury Public Programmes Officer: Ann Betts Margaret Mahy makes her choice 19 MARCH – 11 JULY by indigenous artists of Australasia artist Judy McIntosh Wilson, Gallery Photographer: Brendan Lee and Oceania. continuing her fascination with the A journey through the works of Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery: Marianne Hargreaves marks and tidal tracks imprinted on 4 Noteworthy W.A. Sutton and Ravenscar George D. Valentine, one of New the sandy beaches of Waikuku. News bites from around the Gallery Galleries Zealand’s foremost nineteenth Other Contributors Catalogue available. -

Analysing the Origin of Māui the Semi-Divine Trickster in Polynesian Mythology*

Analysing the Origin of Māui the Semi-Divine Trickster in Polynesian Mythology* Martina Bucková Analýza pôvodu polobožského kultúrneho hrdinu Māuiho v polynézskej mytológii Resumé Kultúrny hrdina Māui je fenomén, ktorý sa objavuje takmer vo všetkých mytologických systémoch Polynézie. Pozoruhodný je jeho pôvod, ktorý je zvyčajne sčasti božský a sčasti ľudský. Príspevok analyzuje rôzne varianty polynézskych mýtov a zameriava sa najmä na informácie týkajúce sa jeho pôvodu, okolností narodenia, varianty mien rodičov a súrodencov. Abstract The cultural hero Māui is a phenomenon that occurs in nearly all the mytholo- gical systems of Polynesia. His origin is remarkable and is mostly partly divine and partly human. This paper analyses different variants of the Polynesian myths about Māui, espe- cially focusing on his origin, the circumstances of his birth and variants of his parents’ names and siblings. Keywords Polynesia, Mythology · Māui, Analysis of Variants in the Tradition A trickster or culture hero is a mythical being found in the mythologies of many archaic societies. In some mythologies, the culture hero is given a divine origin; in others he is a demigod or only a spirit that acts on the command of a higher deity. Prometheus, for example, was of a purely divine origin. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, he was the son of Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene. Māui of Polynesia is an example of a culture hero who was present in most versions of myths of semi-divine origin: in Maori mythology he came from the 156 SOS 13 · 2 (2014) lineage of Tu-mata-uenga, and in Hawaiian mythology his mother was the goddess Hina-a-he-ahi (‘Hina of the fire’). -

Relating Maori and Pakeha : the Politics of Indigenous and Settler

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Relating Maori and Pakeha: the politics of indigenous and settler identities A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology at Massey University Palmerston North New Zealand Avril Bell 2004 Abstract Settler colonisation produced particular colonial subjects: indigene and settler. The specificity of the relationship between these subjects lies in the act of settlement; an act of colonial violence by which the settler physically and symbolically displaces the indigene, but never totally. While indigenes may be physically displaced from their territories, they continue to occupy a marginal location within the settler nation-state. Symbolically, as settlers set out to distinguish themselves from the metropolitan ‘motherlands’, indigenous cultures become a rich, ‘native’ source of cultural authenticity to ground settler nationalisms. The result is a complex of conflictual and ambivalent relations between settler and indigene. This thesis investigates the ongoing impact of this colonial relation on the contemporary identities and relations of Maori (indigene) and Pakeha (settlers) in Aotearoa New Zealand. It centres on the operation of discursive strategies used by both Maori and Pakeha in constructing their identities and the relationship between them. I analyse ‘found’ texts - non-fiction books, media and academic texts - to identify discourse ‘at work’, as New Zealanders make and reflect on their identity claims. -

In Māori Mythology, Tiki Is the First Man Created by Either Tūmatauenga Or Tāne

by Mike Prero In Māori mythology, Tiki is the first man created by either Tūmatauenga or Tāne. He found the first woman, Marikoriko, in a pond; she seduced him and he became the father of Hine-kau-ataata. By extension, a tiki is a large or small wooden or stone carving in humanoid form, although this is a somewhat archaic usage in the Māori language. Carvings similar to tikis and coming to represent deified ancestors are found in most Polynesian cultures. They often serve to mark the boundaries of sacred or significant sites. Tiki carving is one of the oldest art forms known to man, and all original Tiki carvings are unique. Each island culture introduced another variation to the carving technique. In most tiki cultures, Tiki statues carved by high-ranking tribesmen were considered sacred and powerful, and these were used in special reli- gious ceremonies. Tiki statues carved by anyone other than a high-ranking tribesman were used simply as decoration. Some island people still believe in the power of the Tiki, just as some statues are created to be used as fo- cus objects for ceremonies—similar to voodoo rituals. Statues carved with threatening expressions are often used to scare away evil spirits, and others with more amicable expressions are created for use in religious ceremonies, healing services, or to bring good luck. Each individually carved Tiki statue, whether stone or wood, displays the artistic creativity of its time. Many archaeologists believe the statues each have a unique story to tell, and that these specific symbols and carvings represented aspects of ancient life.