Embodied Pedagogy: Examples of Moral Practice from Art Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art's Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki

Art’s Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki This is the text of an illustrated paper presented at ‘Art History's History in Australia and New Zealand’, a joint symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Art History in the University of Melbourne and the Australian and New Zealand Association of Art Historians (AAANZ), held on 28 – 29 August 2010. Responding to a set of questions framed around the ‘state of art history in New Zealand’, this paper reviews the ‘invention’ of a nationalist art history and argues that there can be no coherent, integrated history of art in New Zealand that does not encompass the timeframe of the cultural production of New Zealand’s indigenous Māori, or that of the Pacific nations for which the country is a regional hub, or the burgeoning cultural diversity of an emerging Asia-Pacific nation. On 10 July 2010 I participated in a panel discussion ‘on the state of New Zealand art history.’ This timely event had been initiated by Tina Barton, director of the Adam Art Gallery in the University of Victoria, Wellington, who chaired the discussion among the twelve invited panellists. The host university’s department of art history and art gallery and the University of Canterbury’s art history programme were represented, as were the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the City Gallery, Wellington, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries. The University of Auckland’s department of art history1 and the University of Otago’s art history programme were unrepresented, unfortunately, but it is likely that key scholars had been targeted and were unable to attend. -

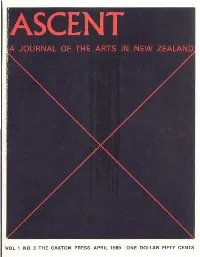

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

E. Mervyn Taylor's Prints on Maori Subjects

THE ENGAGING LINE: E. MERVYN TAYLOR’S PRINTS ON MAORI SUBJECTS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Art History in the University of Canterbury by Douglas Horrell 2006 Contents Contents..................................................................................................................... i Abstract ....................................................................................................................1 Introduction..............................................................................................................2 Chapter One: The making of an artist: history of the development of Taylor’s early career through his close association with Clark, MacLennan, and Woods..................6 Chapter Two: Meeting of worlds: the generation of Taylor’s interest in Maori culture......................................................................................................................19 Chapter Three: Nationalist and local influence: art as identity...............................37 Chapter Four: Grey’s Polynesian Mythology: the opportunity of a career..............46 Chapter Five: A thematic survey of E. Mervyn Taylor’s prints on Maori subjects..56 Conclusion ..............................................................................................................72 Acknowledgements.................................................................................................76 Bibliography...........................................................................................................77 -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

BULLETIN of the CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TE PUNA O WAIWHETU Summer December 03 – February 04

BULLETIN OF THE CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TE PUNA O WAIWHETU summer december 03 – february 04 Open 10am – 5pm daily, late night every Wednesday until 9pm Cnr Worcester Boulevard & Montreal Street, PO Box 2626 Christchurch, New Zealand Tel: (+64 3) 941 7300, Fax: (+64 3) 941 7301 Email: [email protected] www.christchurchartgallery.org.nz Gallery Shop tel: (+64 3) 941 7388 Form Gallery tel: (+64 3) 377 1211 Alchemy Café & Wine Bar tel: (+64 3) 941 7311 Education Booking Line tel: (+64 3) 941 8101 Art Gallery Carpark tel: (+64 3) 941 7350 Friends of the Christchurch Art Gallery tel: (+64 3) 941 7356 b.135 Exhibitions Programme Bulletin Editor: Sarah Pepperle Gallery Contributors 2 Introduction ISLANDS IN THE SUN MAKING TRACKS COMING SOON! Director: Tony Preston A few words from the Director Curator (Contemporary): Felicity Milburn 31 OCTOBER – 1 FEBRUARY 04 13 FEBRUARY – 30 MAY SILICA, SHADOW Curatorial Assistant (Contemporary): Jennifer Hay AND LIGHT Curatorial Assistant (Historical): Ken Hall 3 My Favourite A remarkable collection of prints A unique installation by Canterbury Public Programmes Officer: Ann Betts Margaret Mahy makes her choice 19 MARCH – 11 JULY by indigenous artists of Australasia artist Judy McIntosh Wilson, Gallery Photographer: Brendan Lee and Oceania. continuing her fascination with the A journey through the works of Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery: Marianne Hargreaves marks and tidal tracks imprinted on 4 Noteworthy W.A. Sutton and Ravenscar George D. Valentine, one of New the sandy beaches of Waikuku. News bites from around the Gallery Galleries Zealand’s foremost nineteenth Other Contributors Catalogue available. -

No. Forty One January 1972 President: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw

COA No. Forty one January 1972 president: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw. Exhibitions Officer: Tony Geddes. news The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Receptionist: Jill Goddard. News Editor: A. J. Bisley. 66 Gloucester Street Telephone 67-261 Registered at the Post Office Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine P.O. Box 772 Christchurch Bill Cummings—Oil Marlborough Sounds Series—Kohanga - Marlborough Sounds. March Brian Holmewood and Subject to Adjustment Gallery Calendar Elizabeth Hancock Art School Drawings To 6 January Phillippa Blair National Safety Posters Carl Sydow To 12 January 10 Big Paintings Peter Mardon 6-20 January Manawatu Prints Frits Krijgsman 8-21 January Touring Reproductions April Susan Chaytor Early N.Z. Painting Tom Taylor 26 January Architects (Preview) British Paintings - 13 February Cranleigh Barton Exhibitions mounted with the assistance of the 14-29 February Philip Trusttum Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council through the 11-27 February Annual Autumn Exhibition agency of the Association of N.Z. Art Societies. PAGE ONE C. W. GROVER President's Comment Landscape Design I write this as your new, green as grass presi And Construction dent much aware of the series of distinguished and talented people who have run the Society in the past and wondering if I will be able to 81 Daniels Rd, Christchurch measure up to them. I am quickly beginning to Phone 527-702 appreciate what it means in time and involve ment. Fortunately the Society is in the expert hands of its famous Tweedle-dee and Tweedle dum, the secretary and the treasurer who kindly help the new boy and gently tell him what to do. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21ST CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE NEW COLLECTORS ART THE JIM DRUMMOND COLLECTION THE NEW ZEALAND SALE DECORATIVE ARTS THE 21ST CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE NEW COLLectors art wednesday 22 april 6.30pm THE JIM DRUMMOND COLLECTION saturday 2 may and sunday 3 may 10am please turn to subtitle page for detailed session times THE NEW ZEALAND SALE + DECORATIVE ARTS thursday 14 may 6.30pm RARE BOOKS IN CONJUNCTION WITH paM PLUMBLY a separate catalogue will be available thursday 14 may conditions of sale page 78 absentee bid form page 79 contacts page 80 buyer’s premium on all auctions in this catalogue 15% 3 Abbey Street, Telephone +64 9 354 4646 Newton Freephone 0800 80 60 01 PO Box 68 345, Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 Newton [email protected] Auckland 1145, www.artandobject.co.nz New Zealand entries invited TWENTIETH CENTURY DESIGN TH garth Chester Bob Roukema JUNE 11 2009 Curvesse Chair wing back Chair $3500 - $4000 $2000 - $3000 CONTEMPORARY Len Castle ART + Slab Sided Pot $1000 - $2000 OBJECTS TH Angela Singer MAY 28 2009 Untitled $1000 - $1500 each Peter Peryer IMPORTANT Trout vintage gelatin silver print, 1987 PHOTOGRAPHS $9000 - $14 000 MAY 28TH 2009 One giant leap. The all-new, technologically advanced Lexus RX350 has arrived. Why is the all-new RX350 such an excellent personification of forward thinking? Perhaps it’s the way it innovatively blends the styling of an SUV with the luxury you’ve come to expect from Lexus. With a newly enhanced 3.5 litre engine and Active Torque Control All-Wheel Drive, you’ll have outstanding power coupled with superb response and handling. -

Tui Motu Interislands Monthly Independent Catholic Magazine June 2013 | $6

Tui Motu InterIslands monthly independent Catholic magazine June 2013 | $6 HONE PAPITA RAUKURA ‘RALPH’ HOTERE . editorial a rare diamond hildren are always curious . Daniels was destined for great things spirits soar because of the beauty As a boy of seven or eight, I from birth . A bright child, Ralph and aesthetic power they bring to was fascinated by my moth- excelled easily at primary school, their art . They stop us in our tracks . Cer’s diamond engagement ring . It was winning a boarding scholarship to Ralph’s ventures into such vital issues an unexceptional gold ring set with St . Peter’s Maori School (now Hato as the plight of the Algerian people three small diamonds . However, now Petera College) . Going to Auckland in their search for freedom from I can see why I was entranced . The Teachers College for two years seemed colonial domination, the Cuban mis- exceptional quality of these jewels a logical step forward . And from there, sile crisis, and proposed aluminium shone forth in their beauty and his known ability at art meant he was smelter at Aramoana are at the heart diaphanous colours . A jeweller told sent, in 1952, to Dunedin Teachers of this man’s work . He combined me that the natural quality of the College to train as an arts adviser in in his unique way a Māori heritage diamonds has been enhanced by fine schools . Such is the background of and a thoughtful but fiery spirit that bevelling of the jewels themselves — the man we honour . exposed what was not right in our ‘nature and nurture’ combined to A most important reason for world . -

New Zealand Potter Vol 23/1 Autumn 1981

new zealand potter vol 23/1 autumn 1981 Contents Potters Symposium 2 Don Reitz 3 The New Society 4 John the potter 5 Frank Colson 6 The Raku firings 7 The National Exhibition 8 Crystal gazing 14 Saint Aubyns Potters 16 Honour for potter 22 Kelesita Tasere from Fiji 23 Baroque Politocaust 24 Build your own filter press 26 Air freighting 26 Salute to Bacchus 28 A philosophy of pottery, a standard for judging 30 Waimea Potters. The post-sales-tax Dynasty 33 Royce McGlashen 34 Bumished and primitive fired 37 New Zealand Potter is a non-profit making magazine published twice annually. Circulation is 6,500. The annual subscription is $NZ5.00, for Australia $A6.00, Canada and the United States $US7.00, Britain £4.00 postage included. New Subscriptions should include name and address of subscriber and the issues required. Please mark correspondence ”Subscriptions”. Receipts will not be sent unless asked for. A renewal form is included in the second issue each year. This should be used without delay. It is the only indication that the magazine is still required. Advertising rates Full page 180 mm wide X 250 mm high $280 Half page 180 mm X 122 mm high $154 Quarter page 88 mm wide X 122 mm high $85 Spot 88 mm wide X 58 mm high $46 Offset printing. Unless finished art work ready for camera is supplied by advertiser, the cost of preparing such copy will be added to the above rates. editor: Margaret Harris layout and design: Nigel Harris editorial committee: John Stackhouse, Nigel Harris, Audrey Brodie, Auckland correspondent Barry Brickell moving his terra cottas on the Driving Creek Pottery railway. -

A Comparative Analysis of Content in Maori

MATTERS OF LIFE AND DEATH: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CONTENT IN MAORI TRADITIONAL AND CONTEMPORARY ART AND DANCE AS A REFLECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL MAORI CULTURAL ISSUES AND THE FORMATION AND PERPETUATION OF MAORI AND NON-MAORI CULTURAL IDENTITY IN NEW ZEALAND by Cynthia Louise Zaitz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2009 Copyright by Cynthia Louise Zaitz 2009 ii CURRICULUM VITA In 1992 Cynthia Louise Zaitz graduated magna cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in Drama from the University of California, where she wrote and directed one original play and two musicals. In 1999 she graduated with a Masters in Consciousness Studies from John F. Kennedy University. Since 2003 she has been teaching Music, Theatre and Dance in both elementary schools and, for the last two years, at Florida Atlantic University. She continues to work as a composer, poet and writer, painter, and professional musician. Her original painting, Alcheme 1 was chosen for the cover of Volume 10 of the Florida Atlantic Comparative Studies Journal listed as FACS in Amazon.com. Last year she composed the original music and created the choreography for Of Moon and Madness, a spoken word canon for nine dancers, three drummers, an upright bass and a Native American flute. Of Moon and Madness was performed in December of 2008 at Florida Atlantic University (FAU) and was selected to represent FAU on iTunesU. In April 2009 she presented her original music composition and choreography at FAU in a piece entitled, Six Butts on a Two-Butt Bench, a tongue-in- cheek look at overpopulation for ten actors and seventy dancers. -

Metafiction in New Zealand from the 1960S to the Present Day

Metafiction in New Zealand from the 1960s to the present day A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Matthew Harris 2011 Metafiction in New Zealand from the 1960s to the present day (2011) by Matthew Harris (for Massey University) is licensed under a Creative Commons - Attribution -NonCommercial -NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at www.matthewjamesharris.com. ii ABSTRACT While studies of metafiction have proliferated across America and Europe, the present thesis is the first full-length assessment of its place in the literature of New Zealand. Taking as its point of reference a selection of works from authors Janet Frame, C.K. Stead, Russell Haley, Michael Jackson and Charlotte Randall, this thesis employs a synthesis of contextual and performative frameworks to examine how the internationally- prevalent mode of metafiction has influenced New Zealand fiction since the middle of the 20 th century. While metafictional texts have conventionally been thought to undermine notions of realism and sever illusions of representation, this thesis explores ways in which the metafictional mode in New Zealand since the 1960s might be seen to expand and augment realism by depicting individual modes of thought and naturalising unique forms of self-reflection, during what some commentators have seen as a period of cultural ‘inwardness’ following various socio-political shifts in the latter