Volume 07 Number 01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUCATION of POOR GIRLS in NORTH WEST ENGLAND C1780 to 1860: a STUDY of WARRINGTON and CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland

EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND c1780 to 1860: A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire September 2005 EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND cll8Oto 1860 A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER ABSTRACT This study is an attempt to discover what provision there was in North West England in the early nineteenth century for the education of poor girls, using a comparative study of two towns, Warrington and Chester. The existing literature reviewed is quite extensive on the education of the poor generally but there is little that refers specifically to girls. Some of it was useful as background and provided a national framework. In order to describe the context for the study a brief account of early provision for the poor is included. A number of the schools existing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries continued into the nineteenth and occasionally even into the twentieth centuries and their records became the source material for this study. The eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century were marked by fluctuating fortunes in education, and there was a flurry of activity to revive the schools in both towns in the early nineteenth century. The local archives in the Chester/Cheshire Record Office contain minute books, account books and visitors' books for the Chester Blue Girls' school, Sunday and Working schools, the latter consolidated into one girls' school in 1816, all covering much of the nineteenth century. -

Open Gardens

Festival of Open Gardens May - September 2014 Over £30,000 raised in 4 years Following the success of our previous Garden Festivals, please join us again to enjoy our supporters’ wonderful gardens. Delicious home-made refreshments and the hospice stall will be at selected gardens. We are delighted to have 34 unique and interesting gardens opening this year, including our hospice gardens in Adderbury. All funds donated will benefit hospice care. For more information about individual gardens and detailed travel instructions, please see www.khh.org.uk or telephone 01295 812161 We look forward to meeting you! Friday 23 May, 1pm - 6pm, Entrance £5 to both gardens, children free The Little Forge, The Town, South Newington OX15 4JG (6 miles south west of Banbury on the A361. Turn into The Town opposite The Duck on the Pond PH. Located on the left opposite Green Lane) By kind permission of Michael Pritchard Small garden with mature trees, shrubs and interesting features. Near a 12th century Grade 1 listed gem church famous for its wall paintings. Hospice stall. Wheelchair access. Teas at South Newington House (below). Sorry no dogs. South Newington House, Barford Rd, OX15 4JW (Take the Barford Rd off A361. After 100 yds take first drive on left. If using sat nav use postcode OX15 4JL) By kind permission of Claire and David Swan Tree lined drive leads to 2 acre garden full of unusual plants, shrubs and trees. Richly planted herbaceous borders designed for year-round colour. Organic garden with established beds and rotation planting scheme. Orchard of fruit trees with pond. -

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS Except public holidays Effective from 02 August 2020 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, School 0840 1535 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0723 - 0933 33 1433 - 1633 1743 1843 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0730 0845 0940 40 1440 1540 1640 1750 1850 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0734 0849 0944 then 44 1444 1544 1644 1754 - Great Rollright 0658 0738 0853 0948 at 48 1448 1548 1648 1758 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0747 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1457 1557 1657 1807 - South Newington - - - - times - - - - - 1903 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0626 0716 0758 0911 1006 each 06 1506 1606 1706 1816 - Bloxham Church 0632 0721 0804 0916 1011 hour 11 1511 1611 1711 1821 1908 Banbury, Queensway 0638 0727 0811 0922 1017 17 1517 1617 1717 1827 1914 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0645 0735 0825 0930 1025 25 1525 1625 1725 1835 1921 SATURDAYS 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0838 0933 33 1733 1833 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0845 0940 40 1740 1840 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0849 0944 then 44 1744 - Great Rollright 0658 0853 0948 at 48 1748 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1757 - South Newington - - - times - - 1853 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0716 0911 1006 each 06 1806 - Bloxham Church 0721 0916 1011 hour 11 1811 1858 Banbury, Queensway 0727 0922 1017 17 1817 1904 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0735 0930 1025 25 1825 1911 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Bank Holidays At Easter, Christmas and New Year special timetables will run - please check www.stagecoachbus.com or look out for seasonal publicity This timetable is valid at the time it was downloaded from our website. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

DECEMBER 2018 Price 50P Where Sold

DECEMBER 2018 Price 50p where sold www.barfordnews.co.uk Wishing all our readers a BARFORD VILLAGE MARKET SATURDAY 15TH DECEMBER very Merry 10AM – 12PM Christmas, IN THE VILLAGE HALL your on- JOIN US FOR COMPLIMENTARY going support is so MULLED WINE & MINCE PIES much appreciated. Joan’s beautifully wrapped, deliciously from the Barford News Team tempting chocolates….perfect for Christmas *** Excellent selection of artisan breads *** Moore & Lyon offering home-reared meats and free range hen & duck eggs *** Janet Macey - Of Berry’s Orchard - lovely selection of potted herbs etc. along with a small selection of unique hand decorated pots *** Plus a good range of local producers selling cakes, bread, honey, preserves, greetings cards, wrapping paper & crafts Rapeseed oils, Fairtrade items, hand knitted woollies....and treats for the birds or simply join us for a Cuppa with friends and neighbours!! Come along to sample our wonderful butties with a filling of your choice - bacon / bacon & egg / breakfast bacon, sausage & egg 1 Page PARISH COUNCIL NOTES Removal of the Stage in the Village Hall – The A meeting of the Parish Council took place at responses from parishioners on whether to 7.30pm on 7th November in Barford Village Hall remove the village hall stage were all in favour and was attended by Cllrs Turner, Hobbs, Eden, apart from one. It was agreed to proceed with Cox, Best, County Cllr Fatemian and Mr Best obtaining quotes before the final decision is (Parish Clerk and Responsible Financial Officer) made. and two members of the public. Apologies were received from District Cllr Williams and Cllr Reinforcement of The Green - This work is being Charman. -

Special Meeting of Council

Public Document Pack Special Meeting of Council Tuesday 27 January 2015 Members of Cherwell District Council, A special meeting of Council will be held at Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, OX15 4AA on Tuesday 27 January 2015 at 6.30 pm, and you are hereby summoned to attend. Sue Smith Chief Executive Monday 19 January 2015 AGENDA 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Declarations of Interest Members are asked to declare any interest and the nature of that interest which they may have in any of the items under consideration at this meeting. 3 Communications To receive communications from the Chairman and/or the Leader of the Council. Cherwell District Council, Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX15 4AA www.cherwell.gov.uk Council Business Reports 4 Cherwell Boundary Review: Response to Local Government Boundary Commission for England Draft Recommendations (Pages 1 - 44) Report of Chief Executive Purpose of report To agree Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s (“LGBCE” or “the Commission”) draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council. Recommendations The meeting is recommended: 1.1 To agree the Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council (Appendix 1). 1.2 To delegate authority to the Chief Executive to make any necessary amendments to the council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council prior to submission in light of the resolutions of Council. -

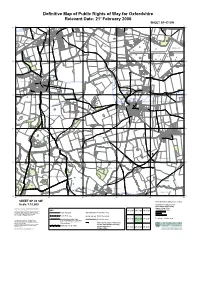

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 43 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 43 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 2800 3500 5900 7300 5300 8300 Pond 0006 0003 5400 0004 5400 0004 5800 0004 A 361 1400 35 Pond 35 Ryehill Barn CLOSE Church Farm 136/9 Factory MANNING 29 Brooklands House Water 8/4a Pond 136/4 Pond 8700 Oak View 8/2 Pavilion 300/7 3587 Drain Happy Valley Farm Milcombe 5800 House Brookside 29 4885 5385 The Cottage Little Stoney 2083 FERNHILL WAY 5783 Hillcroft Laburnum Farnell Fields Hall Farm Milcombe GASCOIGNE House Sallivon Hall BLOXHAM ROAD GASCOIGNE CL 4381 300/2 7380 PAR 298/4 Coombe ADISE LANE Smithy House PO Cottage WAY WAY GASCOIGNE CLOSE Sinks Gleemeade 0080 Smithy Stone Leigh MAULE 0080 Fieldside 8679 1978 Drain Issues BLOXHAM ROAD Bovey The Brompton Farm 3675 Old Barn Pippins 8274 Lea 3774 300/7 Dovecot Manor Manor Ct Drain HORTON LANE Pond Farm Pond 8876 TON ROAD 6872 NG CHURCH LANE Well 5772 SOUTH NEWI BARLOW CL Pond Hall Farm Cotts Reemas Southwynd 3169 Farm 298/9 8068 View 3767 0066 0067 Baytree 1267 298/3 Heath Villa Pond Pond House 0066 Broad Hill View Cottage 2364 Hollies Barn Sinks Horse and Groom (PH) 4560 Jasmine Oak GREEN THE Cottage Hall Farm Houses Council The Old Arnsby Cott 2757 PORTLAND ROAD Spring Pp Ho Mulberry Issues Milcombe CP Arnsby Keytes Cottage St Laurence's Church Blue Pitts BARFORD ROAD HEATH CLOSE Rosery Kingstone Holly Cottage Cottage Westfield Cottag 0049 Slade Farm Rye House Redford House Little Heritage 298/7a e 1152 0052 1650 Birchells Barn 0650 298/8 Pond Ppg Sinks -

The Old Farm SOUTH NEWINGTON • OXFORDSHIRE the Old Farm SOUTH NEWINGTON • OXFORDSHIRE

The Old Farm SOUTH NEWINGTON • OXFORDSHIRE The Old Farm SOUTH NEWINGTON • OXFORDSHIRE Banbury 6 miles, (London/Marylebone from 57 minutes), M40 (J11) about 7 miles, Chipping Norton 7 miles, Oxford 20 miles Immaculate converted barn with generous garden, workshop & stores Dining room, sitting room, snug, study, kitchen/breakfast room, Pantry, utility room & WC 4 bedrooms, 2 bath/shower rooms Detached oak framed double garage Greenhouse, workshop & stores Gated driveway parking Generous gardens & private courtyard About 0.82 acre YOUR ATTENTION IS DRAWN TO THE IMPORTANT NOTICE ON THE LAST PAGE OF THE TEXT LOCATION South Newington is situated in attractive rolling North Oxfordshire countryside between the market towns of Banbury and Chipping Norton close to the Cotswolds. A Conservation Village which includes a public house and a late Norman parish church centred around the ‘Pole Axe’ which is a grass recreational field for children. Local facilities can be found at Bloxham and Chipping Norton. More extensive recreational, leisure and sporting facilities available at Banbury, Oxford, Stratford upon Avon and Leamington Spa. The recently opened Soho Farmhouse at Great Tew is nearby providing a 100 acre estate and members’ club in the Oxfordshire countryside. Excellent education in the area including Great Tew Primary, Warriner senior school, Cotswold school, and private schools include Bloxham, Tudor Hall, Sibford Quaker school and the Oxford schools: The Dragon, Magdalen, St Edwards, and Headington School for Girls. Good communication connections with Junction 11 of the M40 Motorway found at Banbury (approximately 7 miles) for the North and Junction 10 (approximately 11 miles) for the South. A main line train station can be found at Banbury with regular services to London/ Marylebone (from 57 minutes peak time). -

The Blue Coat School Board of Trustees

The Blue Coat School Board of Trustees Joan Bonenfant Joan believes passionately that all children, whatever their background, should have access to education of the highest possible standard and she has dedicated her professional life to putting such ideals into practice. Born and brought up in Liverpool, Joan graduated with a joint honours degree in French and Philosophy. After having worked for a year in France, she studied for a postgraduate certificate in education (PGCE) at Bristol University. Joan then returned to the North West and worked in a number of secondary schools, ending her teaching career as the deputy Role: Chair of Trustees headteacher of a large comprehensive school in St Helens. Appointed: 04/2020 Appointed by: Members The pinnacle of her career, in her view, was when she was Term of office: 04/2024 appointed as one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors and she Voting rights: Full continued in this role for almost ten years, until her recent Declaration of interests: None retirement. Joan is currently the director of her own business Contact: that provides educational consultancy across the region. [email protected] Joan is firmly committed to the belief that education really can have a transformational impact on children’s lives and thus help us to create a better future. Patrick Adamson Patrick is a Deputy Headteacher at a Grammar School in Wirral. He originally studied Maths and Computer Science before working as a Software Engineer on the Seawolf and Rapier anti-aircraft missile systems and on the sonar system for the Trident submarines. He became a Maths teacher in his early thirties and has worked in a variety of schools in the Northwest. -

CORKIN, Ian the Conservative Party Candidate X RE-ELECT

FRINGFORD AND HEYFORDS WARD - THURSDAY 2ND MAY 2019 Cherwell District Council elections - Thursday 2nd May 2019 CORKIN, Ian The Conservative Party Candidate x RE-ELECT Get in touch [email protected] 07841 041419 with Ian: www.iancorkin.yourcllr.com facebook.com/cllriancorkin IAN’S PLAN FOR FRINGFORD AND HEYFORDS WARD: Protect our village way of life and the unique local character of our 1 area by resisting speculative and inappropriate development. Continue to be a strong voice representing your priorities in 2 negotiations and consultations for big infrastructure projects such as HS2, East West Rail and the Oxford to Cambridge Expressway. Enhance our natural environment; delivering the Burnehyll 3 Woodland Project, ensuring Stratton Audley Quarry is protected as a nature reserve and brought into public use and securing the IAN funds to complete the A4421 cycle path. Work with villages to help them develop traffic management and CORKIN 4 calming schemes for the benefit of residents. Support community facilities such as village halls and play areas as well as the volunteers who use them to deliver amazing Your local champion for: 5 services to our residents, children, young people, seniors and military veterans, to name but a few. Ardley with Fewcott, Bainton, Baynards Green, Bucknell, Caulcott, Chesterton, Cottisford, Finmere, Fringford, Promote an innovative and inclusive District housing agenda that 6 delivers affordable homes and has provision for our young Fulwell, Godington, Hardwick, Hethe, Heyford Park, people. Juniper Hill, Kirtlington, Little Chesterton, Champion our vital rural economy and protect our beautiful Lower Heyford, Middleton Stoney, Mixbury, 7 countryside. Newton Morrell, Newton Purcell, Stoke Lyne, Stratton Audley, Tusmore and Upper Heyford Promoted by Alana Powell on behalf of Ian Corkin both of North Oxfordshire Conservative Association, Unit 1a Ockley Barn, Upper Aynho Grounds, Banbury, OX17 3AY. -

'Income Tax Parish'. Below Is a List of Oxfordshire Income Tax Parishes and the Civil Parishes Or Places They Covered

The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is a list of Oxfordshire income tax parishes and the civil parishes or places they covered. ITP name used by The National Archives Income Tax Parish Civil parishes and places (where different) Adderbury Adderbury, Milton Adwell Adwell, Lewknor [including South Weston], Stoke Talmage, Wheatfield Adwell and Lewknor Albury Albury, Attington, Tetsworth, Thame, Tiddington Albury (Thame) Alkerton Alkerton, Shenington Alvescot Alvescot, Broadwell, Broughton Poggs, Filkins, Kencot Ambrosden Ambrosden, Blackthorn Ambrosden and Blackthorn Ardley Ardley, Bucknell, Caversfield, Fritwell, Stoke Lyne, Souldern Arncott Arncott, Piddington Ascott Ascott, Stadhampton Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascot-under-Wychwood Asthall Asthall, Asthall Leigh, Burford, Upton, Signett Aston and Cote Aston and Cote, Bampton, Brize Norton, Chimney, Lew, Shifford, Yelford Aston Rowant Aston Rowant Banbury Banbury Borough Barford St John Barford St John, Bloxham, Milcombe, Wiggington Beckley Beckley, Horton-cum-Studley Begbroke Begbroke, Cutteslowe, Wolvercote, Yarnton Benson Benson Berrick Salome Berrick Salome Bicester Bicester, Goddington, Stratton Audley Ricester Binsey Oxford Binsey, Oxford St Thomas Bix Bix Black Bourton Black Bourton, Clanfield, Grafton, Kelmscott, Radcot Bladon Bladon, Hensington Blenheim Blenheim, Woodstock Bletchingdon Bletchingdon, Kirtlington Bletchington The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is -

Lark Rise Observations

1st July, 2008 Issue 21 Oxfordshire Record Office, St Luke’s Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford, OX4 2HT. Telephone 01865 398200. Email [email protected]: www.oxfordshire.gov.uk LARK RISE OBSERVATIONS THE SMITHY AT FRINGFORD Page 1 SEE PAGES 2 and 3 - for ‘Observations’ 1st July, 2008 Issue 21 LARK RISE OBSERVATIONS Anyone watching the recent BBC adaptations of FloraThompson’s Lark Rise to Candleford trilogy will be aware that, although filmed elsewhere, the novels are set in the north-east corner of Oxfordshire with Lark Rise representing Juniper Hill and Candleford supposedly an amalgam of Banbury, Bicester, Brackley and Buckingham. Flora Thompson (nee Timms) lived at End House in Juniper Hill, a hamlet of Cottisford where she attended the local Board school and church on Sundays. Her job in the post office was at Fringford (about 4-5 miles away). In the novels Flora called herself Laura and in the TV series her parents are called Robert and Emma Timmins. In real life her family name was Timms and her parents were called Albert and Emma. The End House where they lived in Juniper Hill can still be seen today (part of a modern dwelling) and its location can be seen on an OS map, c1900. The Cottisford parish registers reveal that 10 children of Albert and Emma were baptized in the church, starting with Martha on 13th Nov 1875 and ending with Cecil Barrie on 6th Mar 1898 (over 20 years, by which time Emma was in her mid-40s). Four of the children, including Martha, Albert (born 1882), Ellen Mary (born 1893) and Cecil Barrie (buried 4th Apr 1900) died in infancy.