For Richer for Poorer – Poverty and Livelihoods In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

Sharing Life Serving Community

WORSHIPPING GOD SHARING LIFE SERVING COMMUNITY Wychert Vale Benefice Foreword from a close relationship The Bishop of Buckingham with its community in recent years and the The Wychert Vale Benefice is a thriving church recognises 1 Foreword group of rural churches in the heart of this as a significant 2 Brief description of Benefice Buckinghamshire. The Benefice was opportunity which they hope the new 3 Our location recently formed (2016) from two existing appointee will help 4 Our mission smaller benefices and much work has been done in the intervening three years them to grasp. 5 Our strengths to build a strong identity as a single, united During the vacancy, the PCCs have 6 What we want to do benefice. explored different models of team working 7 Type of person we’re looking for Lay leadership within the benefice is well and they are open to exploring with the new incumbent new ways that will help 8 The Benefice churches established, committed and supported by the strong clergy team. The benefice them achieve their vision to worship God, 9 The current team has well-organised structures, including serve their communities and share life. 11 Benefice churches - church a Benefice Council, and benefits from For a priest committed to the diocesan 13 Benefice churches - community part-time administrative support from a vision of becoming a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s World – 14 The Rectory benefice office based in Haddenham. contemplative, compassionate and 15 Church properties The Rector will need to be an able, experienced leader and people manager courageous – this role presents a good 16 Financial summary of our churches who will enable the churches to embrace opportunity to lead mission and ministry in 17 Statistics the challenges and opportunities that lie this exciting context and with a supportive 18 The Diocese and Deanery Information ahead in an area where there is significant team. -

The Bernwode Benefice Bernwodebenefice.Com

The Bernwode Benefice bernwodebenefice.com October 2020 The contents of this profile Foreword Welcome A profile of the Bernwode Benefice The Bernwode Benefice, its location and its parishes Our blessings, challenges and aspirations as a Benefice The effect of COVID-19 Our new rector Job Description and person specification The support we will give you Our Associate Minister – Jenny Edmans Licensed Preacher – Peter Johnson The Benefice and the Parishes Benefice activities Our services, attendances and occasional services The Parishes Practical matters The Vicarage Brill village The wider area The Aylesbury Deanery Vision of the Future and Action Plan The Diocese of Oxford Appendix : Role Description ~ 2 ~ Foreword The seven rural churches of the Bernwode Benefice in north west Buckinghamshire each have committed Churchwardens, supportive laity and strong links with their wider communities. This is an area of great natural beauty which attracts visitors and walkers from the surrounding areas. The churches have, in many ways, drawn closer together during the period of lockdown. The Associate Minister and a lay leader have led a weekly service of compline as well as signposting to other online services. The many who participated from across the benefice have begun to get to know each other better – a positive sign for the future of the benefice. The PCCs have engaged positively with deanery and diocesan advisers during the vacancy and have been open to exploring a more sustainable model of ministry for the future of the benefice. As you will see from the profile, they have identified a number of significant strengths, including their relationship with local schools and the level of support for the churches from within the village communities. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 18/03/2014, 14.00

Buckinghamshire County Council Visit democracy.buckscc.gov.uk for councillor information and email alerts for local meetings BUCKINGHAMSHIRE HISTORIC Agenda ENVIRONMENT FORUM Date: Tuesday 18 March 2014 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Committee Room, Stoke Mandeville Community Centre, Eskdale Road, Stoke Mandeville Agenda Item Page No 1 ELECTION OF CHAIRMAN 2 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE / CHANGES IN MEMBERSHIP 3 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To disclose any Personal or Disclosable Pecuniary Interests 4 MINUTES 1 - 6 of the meeting held on 4 November 2013 to be confirmed 5 MATTERS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 6 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY ARCHAEOLOGY SERVICE REPORTS 7 - 16 • Report of the Senior Archaeology Planning Officer • Report of the Historic Environment Record Officer 7 MILTON KEYNES ARCHAEOLOGICAL OFFICER'S REPORT To Follow 8 EMERGENCY RECORDING FUND REPORT 17 - 18 Report of the Environment Lead Officer 9 COUNTY MUSEUM 19 - 22 Reports of the Keeper of Archaeology and Finds Liaison Officer 10 NATIONAL TRUST REPORT Report of the Regional Archaeologist 11 CHURCH ARCHAEOLOGY Report of the Diocesan Archaeological Adviser 12 CONSERVATION OFFICERS' REPORT • Aylesbury Vale • Chiltern • Milton Keynes • South Bucks • Wycombe 13 ANY OTHER BUSINESS 14 DATE AND TIME OF NEXT MEETING The next meeting is to be held on Thursday 18 September 2014, 2.30pm, Mezz 3, County Hall, Aylesbury, Bucks. If you would like to attend a meeting, but need extra help to do so, for example because of a disability, please contact us as early as possible, so that we can try to put the right support -

Botley Character Statement West Way Community Concern

Botley Character Statement West Way Community Concern 1 Contents A. Introduction to the Botley Character Statement C. Headline Findings D. Location, Context and Layout E. Historical Development F. Character Areas 1. West Way 2. Old Botley 3. Seacourt 4. Westminster Way 5. Arthray Road 6. Cumnor Rise 7. North of West Way 8. Dean Court G. Sources Appendix A. Methodology 2 Section A. Introduction to the Botley Character Statement Local residents and businesses in Botley have joined together to prepare this character statement as a result of concern that new development should respond positively to the area’s established positive character. Local and national planning policies require proposals for new development to take local character into account and respond positively to it in the design of new buildings and spaces and their use. However, defining what the positive features of local character are that should be sustained and what negative feature should be managed out through development is a fundamental stage in this design process and requires assessment, analysis and establishment of consensus. Character assessments are now being undertaken by various community groups, as well as local planning authorities to establish this consensus about what is valued in the character of local areas and neighbourhoods to inform planning for change. To support local communities in undertaking their own assessment of character a number of toolkits have been prepared with the assistance of CABE and English Heritage. These are a recognised means for community groups to prepare character assessments that are sufficiently robust and reliable to be informative for planning decisions. -

Archdeaconry Records

Archdeaconry and peculiar records The Archdeaconry of Oxford was part of the Diocese of Lincoln until the creation of the Diocese of Oxford in 1542. The archdeaconry generated many of the same types of records as the diocese. Because the bishop and archdeacon sometimes used the same officials, there was overlap in the records. It can be difficult to tell which records belong to the Bishop (the Diocesan records) and which to the Archdeacon in the C16th and C17th. The collection contains the records of the Archdeaconry of Oxford and also of peculiar jurisdictions in Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Peculiars were ecclesiastical areas within the Diocese of Oxford, but outside the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Oxford, such as Banbury, Buckingham, Langford, and Thame. In 1836 the Archdeaconry of Berkshire was also transferred to the Diocese of Oxford from the Diocese of Salisbury. In 1845 the Archdeaconry of Buckingham was transferred from the Diocese of Lincoln The court records (ARCH/1) deal with cases concerning the behaviour of the clergy, marriages, morals and religious beliefs of the laity, tithes, wills, church fabric and parish customs. The visitation records (ARCH/2) were created from the visits made by the archdeacon or his officials to every parish every few years. The financial records (ARCH/3) include fees and account books, and procuration books (procurators managed the affairs of other people). The records of clergy (ARCH/4) include mandates for induction of clergy into church livings, sequestration bonds for taking over a benefice (after the resignation or inability of the incumbent clerk in performing their duties) and subscription books including clergy ordination lists and institutions to livings, recording basic information on the names of clerks, their qualifications and careers The parochial records (ARCH/5) contain the annual transcripts of parish register entries. -

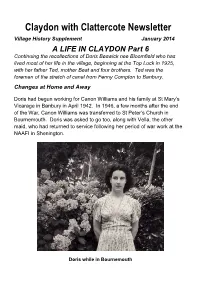

Claydon with Clattercote Newsletter

Claydon with Clattercote Newsletter Village History Supplement January 2014 A LIFE IN CLAYDON Part 6 Continuing the recollections of Doris Beswick nee Bloomfield who has lived most of her life in the village, beginning at the Top Lock in 1925, with her father Ted, mother Beat and four brothers. Ted was the foreman of the stretch of canal from Fenny Compton to Banbury. Changes at Home and Away Doris had begun working for Canon Williams and his family at St Mary’s Vicarage in Banbury in April 1942. In 1946, a few months after the end of the War, Canon Williams was transferred to St Peter’s Church in Bournemouth. Doris was asked to go too, along with Vella, the other maid, who had returned to service following her period of war work at the NAAFI in Shenington. Doris while in Bournemouth The Vicarage in Bournemouth was much smaller than that in Banbury, as was the household. There was only Canon and Mrs Williams and one of their children. In service, there was just Doris and Vella, with Vella taking on the role of cook, but she would also clean the kitchen and help with polishing the silver while Doris was a maid of all trades. As in Banbury, Mrs Williams frequently helped with the chores. With no handyman, Doris took over some of those tasks, such as cleaning the Bishop’s shoes while Mrs Williams relieved Doris of one of her Banbury jobs of cleaning out the grates and setting and lighting the fires. The girls were allowed to take their time off together and the family would organise their meals themselves and do all of the washing up. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 Considerable Work Has Been Done on the Collections, Although Much Still Remains to Be Sorted Out

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 considerable work has been done on the collections, although much still remains to be sorted out. The work of identifying and labelling geological specimens has been completed, and the insect collections sorted, fumi- gated, labelled, put in checklist order and card indexed. The egg collection has also been re-labelled and card indexed, and some specimens added to it. In the historical field a large collection of photographic plates, mainly taken by Taunt of Oxford about 1900, has been sorted and placed in individual envelopes. Racking has been installed in part of the first floor of the stable and most of the collection of pottery sherds transferred to it, where it is easily accessible. A start has been made on the production of a card index of the folk collection and to-date some 1,500 cards have been completed. At short notice reports on archaeological sites in the Chilterns and in the River Ouse Green Belt were prepared, and at greater leisure one on the Vale of Aylesbury for the County Planning Department. This involved visiting a very large number of sites, which did however yield additional information about some. A start has been made on an examination of air photographs of the county, and a number of new sites, particularly of ring ditches and medieval sites, have been found. Excavations were carried out by the museum staff on four sites referred to in The Records, three of them on behalf of the Milton Keynes Research Committee. Amongst the exhibitions was one of Museum Purchases 1960-1970, opened by Earl Howe, Chairman of the County Education Committee, which showed all the purchases made during that period. -

January 2012

Marcham & District News COTHILL – FrilFord – GarFord – Gozzards Ford – MarCHAM – TUBNEY Your Independent Local Newsheet – www.madnews.co.uk January 2012 Vol: 34 No: 1 READ & RECYCLE! FREE ► arthur anson outside the institute in the early 1900s see page 5 (image reproduced by kind permission of Maurice Shepherd) ▲ ► Starting young! a model and plan for a village hall at MCG's Family Event see page 9 ► Santa visiting the toddler group at their Christmas party Holiday WaStE CollECtioNS Please ensure your rubbish bags aren’t left vulnerable to animal and/or bird attack. * Please note on these days collections will start from 6am, an hour earlier than usual, so remember to put your bins out the night before. ▲ Pre School with Normal day Revised day Which bin? giant land snail 'horns' Friday 30 December Tuesday 3 January Grey see page 13 Monday 2 January Wednesday 4 January Green ◄ Mary and Joseph in the stable by Emily Tuesday 3 January Thursday 5 January Green Wednesday 4 January Friday 6 January Green Thursday 5 January Saturday 7 January * Green Friday 6 January Monday 9 January Green Monday 9 January Tuesday 10 January Grey Tuesday 10 January Wednesday 11 January Grey Wednesday 11 January Thursday 12 January Grey Thursday 12 January Friday 13 January Grey Friday 13 January Saturday 14 January * Grey DIARY FOR JANUARY 10 Tue Marcham Society, All Saints’ Church, 19.45 11 20 Fri Deadline for all submissions for February 10 Tue Singing at 62 North Street, 14.00 – 15.30 11 issue of MADNews 11 Wed Marcham Parish Council Meeting, Duffield 3 20 -

Special Meeting of Council

Public Document Pack Special Meeting of Council Tuesday 27 January 2015 Members of Cherwell District Council, A special meeting of Council will be held at Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, OX15 4AA on Tuesday 27 January 2015 at 6.30 pm, and you are hereby summoned to attend. Sue Smith Chief Executive Monday 19 January 2015 AGENDA 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Declarations of Interest Members are asked to declare any interest and the nature of that interest which they may have in any of the items under consideration at this meeting. 3 Communications To receive communications from the Chairman and/or the Leader of the Council. Cherwell District Council, Bodicote House, Bodicote, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX15 4AA www.cherwell.gov.uk Council Business Reports 4 Cherwell Boundary Review: Response to Local Government Boundary Commission for England Draft Recommendations (Pages 1 - 44) Report of Chief Executive Purpose of report To agree Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s (“LGBCE” or “the Commission”) draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council. Recommendations The meeting is recommended: 1.1 To agree the Cherwell District Council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council (Appendix 1). 1.2 To delegate authority to the Chief Executive to make any necessary amendments to the council’s response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft recommendations of the further electoral review for Cherwell District Council prior to submission in light of the resolutions of Council. -

70751 064 RAF Brize Norton ACP Consultation Report Draft A-BZN

ERROR! NO TEXT OF SPECIFIED STYLE IN DOCUMENT. RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal Consultation Feedback Report Document Details Reference Description Document Title RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal Consultation Feedback Report Document Ref 70751 064 Issue Issue 1 Date 3rd October 2018 Issue Amendment Date Issue 1 3rd October 2018 RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal | Document Details ii 70751 064 | Issue 1 Executive Summary RAF Brize Norton (BZN) would like to extend thanks to all the organisations and individuals that took the time to participate and provide feedback to the Public Consultation held between 15th December 2017 and 5th April 2018. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) is the Sponsor of a proposed change to the current arrangements and procedures in the immediate airspace surrounding the airport. As the airport operators, and operators of the current Class D Controlled Airspace (CAS), RAF Brize Norton is managing this process on behalf of the MOD. If approved, the proposed change will provide enhanced protection to aircraft on the critical stages of flight in departure and final approach, and will provide connectivity between the RAF Brize Norton Control Zone (CTR) and the UK Airways network. In addition, the Airspace Change will deliver new Instrument Flight Procedures (IFP) utilising Satellite Based Navigation which will futureproof the procedures used at the Station. As part of the Civil Aviation Authority’s (CAA) Guidance on the Application of the Airspace Change Process (Civil Aviation Publication (CAP) 725) [Reference 1], BZN is required to submit a case to the CAA to justify its proposed Airspace Change, and to undertake consultation with all relevant stakeholders.