The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, a Novel on His Website, the Author Places It in the Public Domain

THE MARVEL UNIVERSE origin stories a NOVEL by BRUCE WAGNER Press Send Press 1 By releasing The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, A Novel on his website, the author places it in the public domain. All or part of the work may be excerpted without the author’s permission. The same applies to any iteration or adaption of the novel in all media. It is the author’s wish that the original text remains unaltered. In any event, The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, A Novel will live in its intended, unexpurgated form at brucewagner.la – those seeking veracity can find it there. 2 for Jamie Rose 3 Nothing exists; even if something does exist, nothing can be known about it; and even if something can be known about it, knowledge of it can't be communicated to others. —Gorgias 4 And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you. —Denis Johnson 5 Book One The New Mutants be careless what you wish for 6 “Now must we sing and sing the best we can, But first you must be told our character: Convicted cowards all, by kindred slain “Or driven from home and left to die in fear.” They sang, but had nor human tunes nor words, Though all was done in common as before; They had changed their throats and had the throats of birds. —WB Yeats 7 some years ago 8 Metamorphosis 9 A L I N E L L Oh, Diary! My Insta followers jumped 23,000 the morning I posted an Avedon-inspired black-and-white selfie/mugshot with the caption: Okay, lovebugs, here’s the thing—I have ALS, but it doesn’t have me (not just yet). -

From Textual Poachers to Textual Gifters: Exploring Fan Community and Celebrity in the Field of Fan Cultural Production

From Textual Poachers to Textual Gifters: Exploring Fan Community and Celebrity in the Field of Fan Cultural Production by Bertha Catherine LP Chin School of Journalism, Media & Cultural Studies Cardiff University 15 November 2010 UMI Number: U584515 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584515 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SUMMARY Early fan studies positioned fans as ‘textual poachers’ (Jenkins, 1992), suggesting that fans poach characters and materials from texts as an act of resistance towards commercial culture to form their own readings through fan cultural production such as fan fiction. As such, fans are often presented as a unified, communal group interacting within the context of fan communities that are considered alternative social communities with ‘no established hierarchy’ (Bacon-Smith, 1992, p. 41). However, Milly Williamson argued that fans do not all operate from a position of cultural marginality. Fans not only go on to collaborate with the media producers they allegedly poach from, they also “engage in elitist distinctions between themselves and other...fans” (Williamson, 2005, p. -

Taste of Race Cancelled, Gala Moved

C M Y K BINGO You may never win an Academy Award, but at least you don’t need a NIGHT designer gown or borrowed jewelry to play Red Carpet bingo B1 Devils blast County to discuss Frostproof attorney, recycling for 4th A7 straight EWS UN A10 LP’s Williams marks NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ 1st year in post A5 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 2, 2014 Taste of Race cancelled, Gala moved ber of Commerce Executive interest and issues getting con- “When I talked to the Sports Gala to be held Friday at track Director Liz Barber said the firmation on the vintage race Car Vintage Racing Associa- chamber board had agreed with cars as the reasons. tion, they couldn’t really guar- BY BARRY FOSTER ficials have reported both the the Heartland Riders Associa- The Circle of Speed was an antee me that cars would be News-Sun correspondent Wednesday afternoon Taste of tion that it would be best not to evening event held before the able to come down or how the Race and the Wednesday continue both the Taste of the annual historic races, while the many,” said Lora Todd of Plan SEBRING — It appears two night Gala will not he held this Race and the Circle of Speed Taste of the Race was staged at B Promotions. “So I’m not will- fan favorites of Race Week will year. Events. noon on the Wednesday before not he happening this year. Of- New Greater Sebring Cham- They cited lack of community the 12 Hours of Sebring. -

Sibling Connections: an Exploration of Adopted People's Birth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Sibling Connections: An Exploration of Adopted People’s Birth and Adoptive Sibling Relationships Across the Life-Span Heather Claire Ottaway Thesis submitted to the University of East Anglia For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis presents a qualitative exploratory study of adopted people’s birth and adoptive sibling relationships across the life-span. Very little is known at present about the longitudinal experience and meaning of these relationships. This study therefore seeks to increase knowledge about how these relationships are developed, maintained and practiced across the life-span from the adopted person’s perspective. Semi- structured interviews were carried out with twenty adopted adults, all of whom had knowledge of at least one birth sibling. Ten participants also had adoptive siblings, who were unrelated and also adopted into the family, or were the birth children of their adoptive parents. Two participants grew up together with one birth sibling and apart from others. Almost three-quarters of the sample who had been reunited with at least one birth sibling had been in contact with them for over 6 years. -

American Dad”

THE PORTRAYAL OF MISOGYNY IN FAMILY REFLECTED IN THE ANIMATED SITCOM “AMERICAN DAD” (2013) THESIS Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Sarjana Degree in English Department of Faculty of Cultural Science, Sebelas Maret University Written by: APRIANTIARA RAHMAWATI SUSMA C0313006 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES SEBELAS MARET UNIVERSITY SURAKARTA 2018 i ii iii PRONOUNCEMENT Name : Apriantiara Rahmawati Susma Student Number : C0313006 The researcher states that the thesis entitled “The Portrayal of Misogyny in Family Reflected in the Animated Sitcom “American Dad” (2013)” is originally written by the researcher and not a part of plagiarism. The explanation of the research is taken by theories and materials from trustable sources with direct quotation and paraphrased citation. The researcher is fully responsible for the pronouncement and if this is proven to be wrong, the researcher is willing to take any responsible actions given by the Faculty of Cultural Science, Sebelas Maret University, including the withdrawal of the degree. Surakarta, 5 January 2018 The researcher Apriantiara Rahmawati Susma iv MOTTO “Successful men and women keep moving. They make mistakes, but they don’t quit” (Conrad Hilton) “I believe in myself and my ability to succeed” (Anonym) v This thesis is wholeheartedly dedicated to: My lovely and supportive parents & Big family of Soedjiman vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The researcher would like to give appreciations to all the persons who help me to finish this thesis. First of all, I would like to thank to Allah SWT for answering my prayers, giving me strength and the ability to finish this thesis, so that I could accomplish the requirements to earn the S1 degree in English Department of Sebelas Maret University. -

Cover Story a Collection of Articles from the Wondercon Anaheim Program Books 2012–2019

COVER STORY A COLLECTION OF ARTICLES FROM THE WONDERCON ANAHEIM PROGRAM BOOKS 2012–2019 All art & characters TM & © DC ® ® COVER STORY: RYAN SOOK WonderCon special guest Ryan Sook is known for his dynamic cover designs, so he was a natural to design this year’s Program Book cover and official T-shirt. Utilizing DC’s New 52 costume designs for its “Big Three” heroes, Ryan came up with a stunning illustration that captures the power of all three color the background ele- After considering what heroes and their respective ments with secondary colors was needed, the sketch worlds. We asked Ryan for his and allow the main imagery came pretty naturally, take on how the cover came to really pop! and the color scheme to be. was formulated at that In the case of this time. For the multiple What’s your initial thought cover, what led you to uses of the art, each fi gure process on designing a piece include the various needed to be usable as a like this, especially since “environments” for each separate and distinct you’re dealing with three such hero? entity. So I penciled iconic characters? each fi gure on a separate Superman is not Superman piece of paper, keeping a ABOVE: Ryan’s original cover sketch. RIGHT: Two of Ryan’s without Krypton as much as close eye on the sketch Initially my thought was to try recent DC New 52 covers, DC Universe Presents #8 (top) and Diana is not a princess un- for size and placement. and capture what has been Justice League Dark #3 (bottom). -

Awnmag5.08.Pdf

Table of Contents NOVEMBER 2000 VOL.5 NO.8 4 Editor’s Notebook A new, healthy beginning… 5 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 6 Belphégor,The Renewed Legend The legend of Belphégor has entranced France for years. Now France 2 and 3 bring the mys- terious dark figure back to television, only this time, it’s animated. Annick Teninge reports. 11 No Boundaries:An Interview With Eric Radomski From Batman: The Animated Series to Spawn and Spicy, Eric Radomski has always been testing the limits of animated TV, while being very vocal about what makes and breaks a show. Amid Amidi passes on the insight. 19 Primetime Animation Fills Growing Niche TV Gerard Raiti studies the migration of animated primetime programming from the major net- works to more specialized networks and reveals that maybe 2000 wasn’t such a bust after all, rather just a shifting of sorts. 2000 24 The Good,The Bad,The Butt-Ugly Martians The Butt-Ugly Martians are about to invade Earth and the World Wide Web simultaneously. Paul Younghusband investigates this strategy’s development and implementation process. 26 Boom and Doom Did primetime television animation fail because it was animated or because it was on big time network TV? Martin Goodman offers new insight on the pressures (and ignorance) influencing the bust of 2000. 30 Tom Snyder Productions Goes Scriptless Sharon Schatz goes behind the scenes at Tom Snyder Productions and learns how this surpris- ing little company has been hitting winners ever since its inception. 34 The Purpose of That X-Chromosome Oxygen’s flagship showcase of animation, X-Chromosome is almost a year old. -

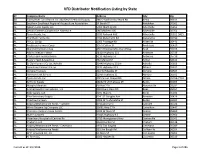

VFD Distributor Notification Listing by State

VFD Distributor Notification Listing by State ST Company Name Address City Zip AK Funny River Fjord Ranch LLC dba Kenai Feed and Supply 38612 Kalifornsky Beach RD Kenai 99611 AK Southern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association 14 Borch ST Ketchikan 99901 AL Asbury Farm Supply LLC 5000 Martling RD Albertville 35951 AL Dekalb Farmers Cooperative Albertville 586 Mitchell AVE Albertville 35951 AL Tyson Foods, Inc. 1100 Railroad AVE Albertville 35951-3425 AL Trantham Farms Inc. 1260 State Farm Rd Alexandria 36250 AL Tri Co. Co-op 1003 Frontage RD Aliceville 35442 AL Andalusia Farmers Coop 305 S Cotton ST Andalusia 36420 AL Marshall Farmers Coop 460 S Brindlee Mountain Pkwy Arab 35016 AL Adams Western Wear 28100 Highway 251 Ardmore 35739 AL Clarks Feed and Hardware 9210 Highway 53 Ardmore 35739 AL Rusty's Feed & Seed LLC 762 Market ST Ariton 36311 AL St Clair Farmers Co-op, Ashville 36440 Highway 231 N Ashville 35953 AL Limestone Farmers Co-op 1910 Highway 31 S Athens 35611 AL Atmore Truckers 210 W Ridgeley ST Atmore 36504 AL Harrison Tack & Feed 11956 Highway 31 Atmore 36502 AL Tyson Foods, Inc. 200 Carnes Chapel RD Attalia 35954-7710 AL KZ Farm Supply 18632 N US Highway 29 Banks 36005 AL Murphy Minerals PO Box 729 Blountsville 35031 AL Animal Health International, Inc. 990 Rivers Oaks RD Boaz 35957 AL Bibb Supply, LLC 2291 Main St Brent 35034 AL Elite Veterinary Supply 624 1/2 Douglas Ave Brewton 36426 AL Choctaw Farmers 1006 W Pushmataha ST Butler 36904 AL Anipro/Xtraformance Feeds - Camden 10 Claiborne ST Camden 36726 AL West Alabama Ag Company LLC 25661 Hwy 17 N Carrollton 35447 AL Cherokee Farmers Coop Centre 1020 W Main ST Centre 35960 AL Mark's Grocery 12005 Highway 9 S Centre 35960 AL Veterinary Hospital of Centreville 1780 Montgomery Hwy Centreville 35042 AL Chatom Feed 16959 Jordan ST Chatom 36518 AL Anipro/Xtraformance Feeds - Cleveland 1650 Tim King Rd Cleveland 35049 AL Anipro/Xtraformance Feeds 333 Jim Baugh Rd Coffeeville 36524 AL W.V. -

As the World Turns

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace@MIT As the World Turns in a Convergence Culture by Samuel Earl Ford B.A. English, Mass Communication, News/Editorial Journalism, Communication Studies Western Kentucky University, 2005 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2007 2007 Samuel Earl Ford. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies 11 May 2007 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: __________________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 1 2 As the World Turns in a Convergence Culture by Samuel Earl Ford Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 11, 2007, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT The American daytime serial drama is among the oldest television genres and remains a vital part of the television lineup for ABC and CBS as what this thesis calls an immersive story world. However, many within the television industry are now predicting that the genre will fade into obscurity after two decades of declining ratings. -

The Salvation Army Valescent Home Patients on Dec

MANCHEST1:R HI-RAI.D, lYiilav, R T I APARTMENTS STORE/OFFICE MISCELLANEOUS CARS FOR RENT FOR RENT I MISCELLANEOUS I j SERVICES FOR SALE m TAG SALE FOR SALE 6 room heated apart liolisf^ ment. $800 with secur GSL Building Mainte MOVING-ln basement FORD, 1971, Maverick. ity. Na pets. 646-2426. nance Co, Commerci- sale. Freezer, kitchen Needs body work. ELLINGTON al/ResIdentlal building E N D R O LLS Runs. $99. Call 647-1824. W e e k d a y s , 9-4.________ 21'h" width — 5041 set, braided rugs, and MEADOWVIEW repairs and home Im D c lit! other Items. December CHEROKEE Jeep, 1977. ONE bedroom apart provements. Interior 13" width — 2 for SOC ment. $550 monthly, ye PLAZA 9, 10-2, 125 Grissom With 1985 motor. $3,500 and exterior painting, Newsprint end rolls can be Road.______________ or best otter. 646-2358. arly lease. Security light carpentry. Com picked up at the Manchester deposit, references re plete janitorial ser Herald ONLY befu'e 11 a m. IN-DOOR Estate Sale-58 DODGE - Omni, 1984. One 1000 sq. ft. Monday through rhuraday. owner. Air condition quired. No pets. Peter vice. Experienced, rel CARPENTRY/ ELECTRICAL Waddell Road, Man man Real Estate. 649- Busy Rte. 83, now 1000 sq. ft. iable, free estimates. chester, Saturday, De ing, A M /FM Cassette, 9404. rental area. In attractive 643-0304. REMODELING cember 9th, 9:30-3:00. cruise, sunroof. $2375. shopping plaza. Ideal for re Furniture, Christmas 646- 5652.________ MANCHESTER - 4 room tail, office, professional, serv DUMAS ELECTRIC apartment.