Lilypond Learning Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

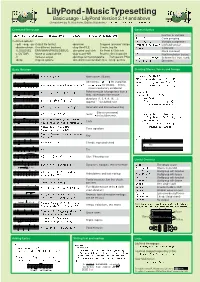

Lilypond Cheatsheet

LilyPond-MusicTypesetting Basic usage - LilyPond Version 2.14 and above Cheatsheet by R. Kainhofer, Edition Kainhofer, http://www.edition-kainhofer.com/ Command-line usage General Syntax lilypond [-l LOGLEVEL] [-dSCMOPTIONS] [-o OUTPUT] [-V] FILE.ly [FILE2.ly] \xxxx function or variable { ... } Code grouping Common options: var = {...} Variable assignment --pdf, --png, --ps Output file format -dpreview Cropped “preview” image \version "2.14.0" LilyPond version -dbackend=eps Use different backend -dlog-file=FILE Create .log file % dots Comment -l LOGLEVEL ERR/WARN/PROG/DEBUG -dno-point-and-click No Point & Click info %{ ... %} Block comment -o OUTDIR Name of output dir/file -djob-count=NR Process files in parallel c\... Postfix-notation (notes) -V Verbose output -dpixmap-format=pngalpha Transparent PNG #'(..), ##t, #'sym Scheme list, true, symb. -dhelp Help on options -dno-delete-intermediate-files Keep .ps files x-.., x^.., x_.. Directions Basic Notation Creating Staves, Voices and Groups \version "2.15.0" c d e f g a b Note names (Dutch) SMusic = \relative c'' { c1\p } Alterations: -is/-es for sharp/flat, SLyrics = \lyricmode { Oh! } cis bes as cisis beses b b! b? -isis/-eses for double, ! forces, AMusic = \relative c' { e1 } ? shows cautionary accidental \relative c' {c f d' c,} Relative mode (change less than a \score { fifth), raise/lower one octave \new ChoirStaff << \new Staff { g1 g2 g4 g8 g16 g4. g4.. durations (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, ...); append “.” for dotted note \new Voice = "Sop" { \dynamicUp \SMusic -

Symantec Web Security Service Policy Guide

Web Security Service Policy Guide Revision: NOV.07.2020 Symantec Web Security Service/Page 2 Policy Guide/Page 3 Copyrights Broadcom, the pulse logo, Connecting everything, and Symantec are among the trademarks of Broadcom. The term “Broadcom” refers to Broadcom Inc. and/or its subsidiaries. Copyright © 2020 Broadcom. All Rights Reserved. The term “Broadcom” refers to Broadcom Inc. and/or its subsidiaries. For more information, please visit www.broadcom.com. Broadcom reserves the right to make changes without further notice to any products or data herein to improve reliability, function, or design. Information furnished by Broadcom is believed to be accurate and reliable. However, Broadcom does not assume any liability arising out of the application or use of this information, nor the application or use of any product or circuit described herein, neither does it convey any license under its patent rights nor the rights of others. Policy Guide/Page 4 Symantec WSS Policy Guide The Symantec Web Security Service solutions provide real-time protection against web-borne threats. As a cloud-based product, the Web Security Service leverages Symantec's proven security technology, including the WebPulse™ cloud community. With extensive web application controls and detailed reporting features, IT administrators can use the Web Security Service to create and enforce granular policies that are applied to all covered users, including fixed locations and roaming users. If the WSS is the body, then the policy engine is the brain. While the WSS by default provides malware protection (blocks four categories: Phishing, Proxy Avoidance, Spyware Effects/Privacy Concerns, and Spyware/Malware Sources), the additional policy rules and options you create dictate exactly what content your employees can and cannot access—from global allows/denials to individual users at specific times from specific locations. -

Latexsample-Thesis

INTEGRAL ESTIMATION IN QUANTUM PHYSICS by Jane Doe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mathematics The University of Utah May 2016 Copyright c Jane Doe 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Jane Doe has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Cornelius L´anczos , Chair(s) 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Hans Bethe , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Niels Bohr , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Max Born , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Paul A. M. Dirac , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved by Petrus Marcus Aurelius Featherstone-Hough , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Mathematics and by Alice B. Toklas , Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. -

![Archive and Compressed [Edit]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8796/archive-and-compressed-edit-1288796.webp)

Archive and Compressed [Edit]

Archive and compressed [edit] Main article: List of archive formats • .?Q? – files compressed by the SQ program • 7z – 7-Zip compressed file • AAC – Advanced Audio Coding • ace – ACE compressed file • ALZ – ALZip compressed file • APK – Applications installable on Android • AT3 – Sony's UMD Data compression • .bke – BackupEarth.com Data compression • ARC • ARJ – ARJ compressed file • BA – Scifer Archive (.ba), Scifer External Archive Type • big – Special file compression format used by Electronic Arts for compressing the data for many of EA's games • BIK (.bik) – Bink Video file. A video compression system developed by RAD Game Tools • BKF (.bkf) – Microsoft backup created by NTBACKUP.EXE • bzip2 – (.bz2) • bld - Skyscraper Simulator Building • c4 – JEDMICS image files, a DOD system • cab – Microsoft Cabinet • cals – JEDMICS image files, a DOD system • cpt/sea – Compact Pro (Macintosh) • DAA – Closed-format, Windows-only compressed disk image • deb – Debian Linux install package • DMG – an Apple compressed/encrypted format • DDZ – a file which can only be used by the "daydreamer engine" created by "fever-dreamer", a program similar to RAGS, it's mainly used to make somewhat short games. • DPE – Package of AVE documents made with Aquafadas digital publishing tools. • EEA – An encrypted CAB, ostensibly for protecting email attachments • .egg – Alzip Egg Edition compressed file • EGT (.egt) – EGT Universal Document also used to create compressed cabinet files replaces .ecab • ECAB (.ECAB, .ezip) – EGT Compressed Folder used in advanced systems to compress entire system folders, replaced by EGT Universal Document • ESS (.ess) – EGT SmartSense File, detects files compressed using the EGT compression system. • GHO (.gho, .ghs) – Norton Ghost • gzip (.gz) – Compressed file • IPG (.ipg) – Format in which Apple Inc. -

Real-Time Generation of Music Notation Via Audience Interaction Using Python and GNU Lilypond Kevin C

Proceedings of the 2005 International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME05), Vancouver, BC, Canada Real-Time Generation of Music Notation via Audience Interaction Using Python and GNU Lilypond Kevin C. Baird University at Buffalo 222 Baird Hall Amherst, NY 14221 01-716-564-1172 [email protected] ABSTRACT 2.2Storage as MusicXML No Clergy is an interactive music performance/installation in In order to perform stochastic transformations on the notation, which the audience is able to shape the ongoing music. In it, No Clergy needs some method of storing musically significant members of a small acoustic ensemble read music notation from information about each page of notation. I chose Recordare's computer screens. As each page refreshes, the notation is altered MusicXML, described by them as “a universal translator for and shaped by both stochastic transformations of earlier music common Western musical notation from the 17th century with the same performance and audience feedback, collected via onwards. It is designed as an interchange format for notation, standard CGI forms. analysis, retrieval, and performance applications.”[10] Each most recent XML file is accessed during the generation of subsequent Keywords pages of notation, while older files are compressed and stored. notation, stochastic, interactive, audience, Python, Lilypond 2.3Rendering of Notation Markup 1.INTRODUCTION After the “conductor” has executed the bash wrapper script, it No Clergy currently runs on a Debian GNU/Linux system. The will then have created one GNU Lilypond markup file for each ideal performance setting has one person serving as the instrument. Lilypond is a Scheme-based music typesetting “conductor” logged in to a shell on the server. -

Lilypond Informations Générales

LilyPond Le syst`eme de notation musicale Informations g´en´erales Equipe´ de d´eveloppement de LilyPond Copyright ⃝c 2009–2020 par les auteurs. This file documents the LilyPond website. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. Pour LilyPond version 2.21.82 1 LilyPond ... la notation musicale pour tous LilyPond est un logiciel de gravure musicale, destin´e`aproduire des partitions de qualit´e optimale. Ce projet apporte `al’´edition musicale informatis´ee l’esth´etique typographique de la gravure traditionnelle. LilyPond est un logiciel libre rattach´eau projet GNU (https://gnu. org). Plus sur LilyPond dans notre [Introduction], page 3, ! La beaut´epar l’exemple LilyPond est un outil `ala fois puissant et flexible qui se charge de graver toutes sortes de partitions, qu’il s’agisse de musique classique (comme cet exemple de J.S. Bach), notation complexe, musique ancienne, musique moderne, tablature, musique vocale, feuille de chant, applications p´edagogiques, grands projets, sortie personnalis´ee ainsi que des diagrammes de Schenker. Venez puiser l’inspiration dans notre galerie [Exemples], page 6, 2 Actualit´es ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, [Actualit´es], page 103, i Table des mati`eres -

Lilypond Allgemeine Information

LilyPond Das Notensatzsystem Allgemeine Information Das LilyPond-Entwicklungsteam Copyright ⃝c 2009–2020 by the authors. Diese Datei dokumentiert den Internetauftritt von LilyPond. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. F¨ur LilyPond Version 2.22.1 1 LilyPond ... Notensatz f¨ur Jedermann LilyPond ist ein Notensatzsystem. Das erkl¨arte Ziel ist es, Notendruck in bestm¨oglicher Qua- lit¨atzu erstellen. Mit dem Programm wird es m¨oglich, die Asthetik¨ handgestochenen traditio- nellen Notensatzes mit computergesetzten Noten zu erreichen. LilyPond ist Freie Software und Teil des GNU-Projekts (https://gnu.org). Lesen Sie mehr in der [Einleitung], Seite 3! Sch¨oner Notensatz LilyPond ist ein sehr m¨achtiges und flexibles Werkzeug, das Notensatz unterschiedlichster Art handhaben kann: zum Beispiel klassische Musik (wie in diesem Beispiel von J. S. Bach), komplexe Notation, Alte Musik, moderne Musik, Tabulatur, Vokalmusik, Popmusik, Unterrichts- materialien, große Orchesterpartituren, individuelle L¨osungen und sogar Schenker-Graphen. Sehen Sie sich unsere [Beispiele], Seite 6, an und lassen sich inspirieren! 2 Neuigkeiten ⟨undefined⟩ [News], Seite ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], Seite ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], Seite ⟨undefined⟩, i Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung.................................................. -

Integral Estimation in Quantum Physics

INTEGRAL ESTIMATION IN QUANTUM PHYSICS by Jane Doe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematical Physics Department of Mathematics The University of Utah May 2016 Copyright c Jane Doe 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Jane Doe has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Cornelius L´anczos , Chair(s) 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Hans Bethe , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Niels Bohr , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Max Born , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Paul A. M. Dirac , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved by Petrus Marcus Aurelius Featherstone-Hough , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Mathematics and by Alice B. Toklas , Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. -

Snippets.Pdf

LilyPond The music typesetter Snippets The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This document shows a selected set of LilyPond snippets from the LilyPond Snippet Repository (http://lsr.di.unimi.it) (LSR). It is in the public domain. We would like to address many thanks to Sebastiano Vigna for maintaining LSR web site and database, and the University of Milano for hosting LSR. Please note that this document is not an exact subset of LSR: some snippets come from input/new LilyPond sources directory, and snippets from LSR are converted through convert-ly, as LSR is based on a stable LilyPond version, and this document is for version 2.22.1. Snippets are grouped by tags; tags listed in the table of contents match a section of LilyPond notation manual. Snippets may have several tags, and not all LSR tags may appear in this document. In the HTML version of this document, you can click on the file name or figure for each example to see the corresponding input file. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ This document has been placed in the public domain. For LilyPond version 2.22.1 i Table of Contents Pitches ................................................... ........... 1 Adding ambitus per voice ................................................... ............ 1 Adding an ottava marking to a single voice .............................................. 1 Aiken head thin variant noteheads................................................... .... 2 Altering the length of beamed stems................................................... .. 2 Ambitus after key signature .................................................. -

Release Notes for Fedora 17

Fedora 17 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 17 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2012 Fedora Project Contributors. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Interpreting the Semantics of Music Notation Using an Extensible and Object-Oriented System

Interpreting the semantics of music notation using an extensible and object-oriented system Michael Droettboom, Ichiro Fujinaga Peabody Conservatory of Music Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Abstract This research builds on prior work in Adaptive Optical Music Recognition (AOMR) (Fujinaga 1996) to create a system for the interpretation of musical semantics. The existing AOMR system is highly extensible, allowing the end user to add new symbols and types of notations at run-time. It was therefore imperative that the new system have the ability to easily define the musical semantics of those new symbols. Python proved to be an effective tool with which to build an elegant and extensible system for the interpretation of musical semantics. 1 Introduction In recent years, the availability of large online databases of text have changed the face of scholarly research. While those same collections are beginning to add multimedia content, content-based retrieval on such non-textual data is significantly behind that of text. In the case of music notation, captured images of scores are not sufficient to perform musically meaningful searches and analyses on the musical content itself. For instance, an end user may wish to find a work containing a particular melody, or a musicologist may wish to perform a statistical analysis of a particular body of work. Such operations require a logical representation of the musical meaning of the score. However, to date, creating those logical representations has been very expensive. Common methods of input include manually enter- ing data in a machine-readable format (Huron and Selfridge-Field 1994) or hiring musicians to play scores on MIDI keyboards (Selfridge-Field 1993). -

Debian Build Dependecies

Debian build dependecies Valtteri Rahkonen valtteri.rahkonen@movial.fi Debian build dependecies by Valtteri Rahkonen Revision history Version: Author: Description: 2004-04-29 Rahkonen Changed title 2004-04-20 Rahkonen Added introduction, reorganized document 2004-04-19 Rahkonen Initial version Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................1 2. Required source packages.....................................................................................................................2 2.1. Build dependencies .....................................................................................................................2 2.2. Misc packages .............................................................................................................................4 3. Optional source packages......................................................................................................................5 3.1. Build dependencies .....................................................................................................................5 3.2. Misc packages ...........................................................................................................................19 A. Required sources library dependencies ............................................................................................21 B. Optional sources library dependencies .............................................................................................22