A Phenomenological Analysis of the Transcendental Ability of Time in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

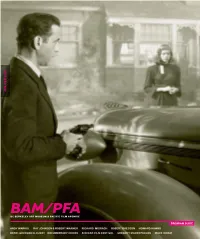

BAM/PFA Program Guide

B 2012 B E N/F A J UC BERKELEY ART MUSEum & PacIFIC FILM ARCHIVE PROGRAM GUIDE AnDY WARHOL RAY JOHNSON & ROBERT WARNER RICHARD MISRACH rOBERT BRESSON hOWARD HAWKS HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOt dOCUMENTARY VOICES aFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL GREGORY MARKOPOULOS mARK ISHAM BAM/PFA EXHIBITIONS & FILM SERIES The ReaDinG room P. 4 ANDY Warhol: PolaroiDS / MATRIX 240 P. 5 Tables OF Content: Ray Johnson anD Robert Warner Bob Box ArchiVE / MATRIX 241 P. 6 Abstract Expressionisms: PaintinGS anD DrawinGS from the collection P. 7 Himalayan PilGrimaGE: Journey to the LanD of Snows P. 8 SilKE Otto-Knapp: A liGht in the moon / MATRIX 239 P. 8 Sun WorKS P. 9 1 1991: The OAKlanD-BerKeley Fire Aftermath, PhotoGraphs by RicharD Misrach P. 9 RicharD Misrach: PhotoGraphs from the Collection State of MinD: New California Art circa 1970 P. 10 THOM FaulDers: BAMscape Henri-GeorGes ClouZot: The Cinema of Disenchantment P. 12 Film 50: History of Cinema, Film anD the Other Arts P. 14 BehinD the Scenes: The Art anD Craft of Cinema Composer MARK Isham P. 15 African film festiVal 2012 P. 16 ScreenaGers: 14th Annual Bay Area HIGH School Film anD ViDeo FestiVal P. 17 HowarD HawKS: The Measure of Man P. 18 Austere Perfectionism: The Films of Robert Bresson P. 21 Documentary Voices P. 24 SeconDS of Eternity: The Films of GreGory J. MarKopoulos P. 25 DiZZY HeiGhts: Silent Cinema anD Life in the Air P. 26 Cover GET MORE The Big Sleep, 3.13.12. See Hawks series, p. 18. Want the latest program updates and event reminders in your inbox? Sign up to receive our monthly e-newsletter, weekly film update, 1. -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Cutting and Framing in Bauer's and Kuleshov' S Films

YURI TSIVIAN Cutting and framing in Bauer's and Kuleshov' s Films This article deals with what looks like the most intriguing aspect of silent cinema in Russia as it passed from its pre-revolutionary period to the period known as the clas sical Soviet montage school. In terms of style filmmakers seemed to have run from one extreme to another. Almost overnight, long shots and long takes, typical for Russian films of the 1910s, gave way to close framing and fast cutting. In this article I am going to address the issue of cutting rate as related to the emerging notion of 'effi cient narrative' and that of closer framing as conflicting with previously established ways of representing the filmic space. Yevgeni Bauer and Lev Kuleshov have been picked out as contrasting figures; besides, in the last years of Bauer's lifetime Kules hov had been his devoted pupil, so the change in style is set off by the continuity of generations. 1. Face versus Space What was the chronology of the facial close-up in early Russian cinema? An exami nation of existing archival holdings is not very rewarding - only about ten per cent of all Russian film output of the teens has survived, and, what is still worse, this percen tage does not equally represent different studio productions. Khanzhonkov's studio style is fairly well known, while we have almost no idea what was the close-up policy of, say, Thieman and Reinhardt studio directors. Memoir sources are interesting but particularly unreliable in regards to close ups. -

300 Greatest Films 4 Black Copy

The goal in this compilation was to determine film history's definitive creme de la creme. The titles considered to be the greatest of the great from around the world and throughout the history of film. So, after an in-depth analysis of respected critics and publications from around the globe, cross-referenced and tweaked to arrive at the ranking of films representing, we believe, the greatest cinema can offer. Browse, contemplate, and enjoy. Check off all the films you have seen 1 Citizen Kane 1941 USA 26 The 400 Blows 1959 France 51 Au Hasard Balthazar 1966 France 76 L.A. Confidential 1997 USA 2 Vertigo 1958 USA 27 Satantango 1994 Hungary 52 Andrei Rublev 1966 USSR 77 Modern Times 1936 USA 3 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 UK 28 Raging Bull 1980 USA 53 All About Eve 1950 USA 78 Mr Hulot's Holiday 1952 France 4 The Rules of the Game 1939 France 29 L'Atalante 1934 France 54 Sunset Boulevard 1950 USA 79 Wings of Desire 1978 France 5 Seven Samurai 1954 Japan 30 Annie Hall 1977 USA 55 The Turin Horse 2011 Hungary 80 Ikiru 1952 Japan 6 The Godfather 1972 USA 31 Persona 1966 Sweden 56 Jules and Jim 1962 France 81 The Apartment 1960 USA 7 Apocalypse Now 1979 USA 32 Man With a Movie Camera 1929 USSR 57 Double Indemnity 1944 USA 82 Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie 1972 France 8 Tokyo Story 1953 Japan 33 E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 1982 USA 58 Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963 France 83 The Seventh Seal 1957 Sweden 9 Taxi Driver 1976 USA 34 Star Wars Episode IV 1977 USA 59 Belle De Jour 1967 France 84 Wild Strawberries 1957 Sweden 10 Casablanca 1942 USA 35 -

Video Production 101: Delivering the Message

VIDEO PRODUCTION VIDEO PRODUCTION 101 101 Delivering the Message Antonio Manriquez & Thomas McCluskey VIDEO PRODUCTION 101 Delivering the Message Antonio Manriquez & Thomas McCluskey Video Production 101 Delivering the Message Antonio Manriquez and Thomas McCluskey Peachpit Press Find us on the Web at www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education Copyright © 2015 by Antonio Jesus Manriquez and Thomas McCluskey Senior Editor: Karyn Johnson Development Editor: Stephen Nathans-Kelly Senior Production Editor: Tracey Croom Copyeditor and Proofreader: Kim Wimpsett Compositor: Danielle Foster Indexer: Jack Lewis Interior Design: Danielle Foster Cover Design: Aren Straiger Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the authors nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

Rosetta Stone: a Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers' Rosetta

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 6 Issue 1 April 2002 Article 7 April 2002 Rosetta Stone: A Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers' Rosetta Bert Cardullo [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Cardullo, Bert (2002) "Rosetta Stone: A Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers' Rosetta," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol6/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rosetta Stone: A Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers' Rosetta Abstract The Dardenne brothers' Rosetta has Christian overtones despite its unrelieved bleakness of tone. In fact, the titular heroine, a teenaged Belgian girl living in dire, subproletarian poverty, has much in common with Robert Bresson's protagonists Mouchette and Balthasar. Both Mouchette (1966) and Au hasard Balthasar (1966) are linked with Rosetta in their examination of the casual, gratuitous inhumanity to which the meek of this earth are subjected, and both films partake of a religious tradition, or spiritual style, dominated by French Catholics like Bresson, Cavalier, Pialat, and Doillon. Those who have argued that the Dardennes' film is merely a documentary-like chronicle of a depressing case choose to ignore this work's religious element, in addition to the fact that Rosetta, unlike Mouchette or Balthasar, is alive and in the good company of a genuine human spirit at the end. -

Visnja Diss FINAL

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles ! ! ! ! Clint Mansell: Music in the Films Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky ! ! ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music ! by ! Visnja Krzic ! ! 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © Copyright by Visnja Krzic 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ! Clint Mansell: Music in the Films Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky ! by ! Visnja Krzic Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair ! This monograph examines how minimalist techniques and the influence of rock music shape the film scores of the British film composer Clint Mansell (b. 1963) and how these scores differ from the usual Hollywood model. The primary focus of this study is Mansell’s work for two films by the American director Darren Aronofsky (b. 1969), which earned both Mansell and Aronofsky the greatest recognition: Requiem for a Dream (2000) and The Fountain (2006). This analysis devotes particular attention to the relationship between music and filmic structure in the earlier of the two films. It also outlines a brief evolution of musical minimalism and explains how a composer like Clint Mansell, who has a seemingly unusual background for a minimalist, manages to meld some of minimalism’s characteristic techniques into his own work, blending them with aspects of rock music, a genre closer to his musical origins. This study also characterizes the film scoring practices that dominated Hollywood scores throughout the ii twentieth century while emphasizing the changes that occurred during this period of history to enable someone with Mansell’s background to become a Hollywood film composer. -

Au Hazard Balthazar 1966

21 MARCH 2006, XII:9 ROBERT BRESSON: Au hazard Balthazar 1966. 95 min. Directed by Robert Bresson Written by Robert Bresson Produced by Mag Bodard Original Music by Jean Wiener Non-Original Music by Franz Schubert (from "Piano Sonata No.20") Cinematography by Ghislain Cloquet Film Editing by Raymond Lamy Animal trainer: Guy Renault Anne Wiazemsky....Marie François Lafarge....Gérard Philippe Asselin....Marie's father Nathalie Joyaut....Marie's mother Walter Green....Jacques Jean-Claude Guilbert....Arnold Pierre Klossowski....Merchant François Sullerot ....Baker Marie-Claire Fremont....Baker's wife Jean Rémignard.... Notary ROBERT BRESSON (25 September 1901, Bromont-Lamothe, Puy-de-Dôme, Auvergne, France—18 December 1999, Paris, natural causes) directed 14 films and wrote 17 screenplays. The films he directed were L'Argent/Money (1983), Le Diable probablement/The Devil Probably (1977), Lancelot du lac (1974), Quatre nuits d'un rêveur/Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), Une femme douce/A Gentle Woman (1969), Mouchette (1967), Au hasard Balthazar/Balthazar (1966), Procès de Jeanne d'Arc/Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), Pickpocket (1959), A Man Escaped (1956), Journal d'un curé de campagne/Diary of a Country Priest (1951), Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne/Ladies of the Park (1945), Les Anges du péché/Angels of the Street (1943) and Les Affaires publiques/Public Affairs (1934). Ghislain Cloquet (18 April 1924, Antwerp, Belgium--November 1981) shot 55 films, among them Four Friends (1981), The Secret Life of Plants (1979), Tess (1979, won Oscar), Love and Death (1975), Mouchette (1967), Loin du Vietnam/Far from Vietnam (1967), Mickey One (1965), Le Trou (1960), Nuit et brouillard/Night and Fog (1955). -

Continuity Editing for 3D Animation

Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence Continuity Editing for 3D Animation Quentin Galvane Remi´ Ronfard Christophe Lino Marc Christie INRIA INRIA INRIA IRISA Univ. Grenoble Alpes & LJK Univ. Grenoble Alpes & LJK Univ. Grenoble Alpes & LJK University of Rennes I Abstract would, at least partially, support users in their creative pro- cess (Davis et al. 2013). We describe an optimization-based approach for auto- Previous contributions in automatic film editing have fo- matically creating well-edited movies from a 3D an- cused on generative methods mixing artificial intelligence imation. While previous work has mostly focused on the problem of placing cameras to produce nice-looking and computer graphics techniques. However, evaluating the views of the action, the problem of cutting and past- quality of film editing (whether generated by machines or by ing shots from all available cameras has never been ad- artists) is a notoriously difficult problem (Lino et al. 2014). dressed extensively. In this paper, we review the main Some contributions mention heuristics for choosing between causes of editing errors in literature and propose an edit- multiple editing solutions without further details (Christian- ing model relying on a minimization of such errors. We son et al. 1996) while other minimize a cost function which make a plausible semi-Markov assumption, resulting in is insufficiently described to be reproduced (Elson and Riedl a dynamic programming solution which is computation- 2007). Furthermore, the precise timing of cuts has not been ally efficient. We also show that our method can gen- addressed, nor the problem of controling the rhythm of cut- erate movies with different editing rhythms and vali- ting (number of shots per minute) and its role in establish- date the results through a user study. -

Mouchette Free

FREE MOUCHETTE PDF Georges Bernanos,J. C. Whitehouse,Fanny Howe | 156 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | The New York Review of Books, Inc | 9781590171516 | English | New York, United States Mouchette () | The Criterion Collection With her innocent salutation and claims to be "nearly thirteen" [1] greeting the visitor from the introduction page, what initially appears as a Mouchette website of an underage female artist evolves into darker themes in the subsequent pages. Mouchette is loosely based on a book by Mouchette Bernanos and the Robert Bresson movie, Mouchette. The storyline is Mouchette a French teenager who commits suicide after she Mouchette raped. An online quiz comparing the "Neo-Mouchette" [2] to the movie angered Bresson's widow, so she threatened a lawsuit against the artist behind the project. The quiz was taken down after that incident. The creator of the website has been a closely guarded secret, [3] though the piece has recently been claimed by artist Martine Neddam. Martine Neddam has since created a page where she explains Mouchette. Mouchette the use of taboo subject matters are what Mouchette "provokes heated reactions", [3] the manipulation of cyber identity [3] and the ability of the creator to maintain anonymity Mouchette so long are the significant reasons this website Mouchette garnered its "international reputation" [5] in the Internet art community. Mouchette simple and "deceptively innocent" [3] introduction, which appears Mouchette to a portrait of a "sad eyed" [2] adolescent girl Mouchette the main page with a floral background, is in stark contrast to the complexity of the rest of the site. Consisting "of various secret links, electronic interactive texts, and poems that reveal the multiple faces of Mouchette artist, Mouchette with her Mouchette and obsessions", [6] participants of the website are often left wondering whether "a website this sophisticated [could] Mouchette be the work of a 13 year old Mouchette. -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by James Michael Churchill 2020 The Thesis Committee for James Michael Churchill Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Zen and the Art of Minimalist Maintenance: Eastern Philosophy in the Cinematic Method of Robert Bresson APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Charles Ramirez-Berg, Supervisor Thomas G. Schatz Zen and the Art of Minimalist Maintenance: Eastern Philosophy in the Cinematic Method of Robert Bresson by James Michael Churchill Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Abstract Zen and the Art of Minimalist Maintenance: Eastern Philosophy in the Cinematic Method of Robert Bresson James Michael Churchill, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2020 Supervisor: Charles Ramirez-Berg This study examines the presence of Zen Buddhism in Robert Bresson’s unique method of film construction. I argue that Bresson’s minimalist choices regarding film form and his emphasis on sensory experience at the expense of intellectual analysis overlap significantly with Zen. In addition, I explore Bresson’s unique theory of film acting and discuss the parallels between his idea of the actor-as-model and the process of transcending the self through Zen meditation. The aim of this thesis is to open the door to a new approach to film studies: a method that highlights direct experience and the achievement of a meditative state as opposed to the Western tradition of critical thinking and conceptual analysis. iv Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................