Conversations About Great Films with Diane Christian & Bruce Jackson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

OIL MILL GAZETTEER Official Organ of the National Oil Mill Superintendents’ Association

OIL MILL GAZETTEER Official Organ of the National Oil Mill Superintendents’ Association. VOL. X V Ii., NO. 10. WHARTON, TEXAS, APRIL, 1916. PRICE TEN CENTS From Secretary-Treasurer Morris It is unnecessary for me to go into details vention, and certainly hope I will succeed much concerning our next convention, for President better. Leonard’s letter in the March issue was to the Let everybody boost for the convention and point and brings out in full everything connect be sure to be on hand yourself. Yours to ed with our next meeting. However, I want to serve, F. P. MORRIS, impress upon the minds of all members that in Secretary-Treasurer. order to succeed as we have planned, you must * * * attend. Let’s make this our banner meeting BIG FIRE LOSS AT TYLER year. I have letters from superintendents from California to North Carolina expressing their Tyler, Texas, March 17.— The Tyler Oil desire to be there, and if nothing prevents, you Company and the Tyler Ice Company suffered a will see them. Now then, let’s all who live, fire loss last night of between $25,000 and closer be on hand. The meeting has been ad $30,000. The oil company lost its big seed house, vertised throughout all cotton growing states, in which there was no seed, and its hull house, and I will continue to do so from now until the in which was stored a large quantity of hulls. convention meets. If President Leonard and The damage to the walls of the large mill build myself, assisted very ably by our never tiring ing will amount to several thousand dollars. -

Filmar As Sensações

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM FILOSOFIA Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson São Paulo 2012 Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson Tese apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em Filosofia do Departamento de Filosofia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Filosofia sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Luiz Fernando B. Franklin de Matos. São Paulo 2012 Ao pequeno Hiro, grande herói, dedico esse trabalho. “Tão longe que se vá, tão alto que se suba, é preciso começar por um simples passo.” Shitao. Agradecimentos À CAPES, pela bolsa concedida. À Marie, Maria Helena, Geni e a todo o pessoal da secretaria, pela eficiência e por todo o apoio. Aos professores Ricardo Fabbrini e Vladimir Safatle, pela participação na banca de qualificação. Ao professor Franklin de Matos, meu orientador e mestre de todas as horas. A Jorge Luiz M. Villela, pelo incentivo constante e pelo abstract. A José Henrique N. Macedo, aquele que ama o cinema. Ao Dr. Ricardo Zanetti e equipe, a quem devo a vida de minha esposa e de meu filho. Aos meus familiares, por tudo e sempre. RESUMO TAKAYAMA, L. R. Filmar as sensações: cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson. 2012. 186 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas. Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2012. -

Reset MODERNITY!

reset MODERNITY! FIELD BOOK ENGLISH reset MODERNITY! 16 Apr. – 21 Aug. 2016 ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe What do you do when you are disoriented, when the compass on your smartphone goes haywire? You reset it. The procedure varies according to the situ- ation and device, but you always have to stay calm and follow instructions carefully if you want the compass to capture signals again. In the exhibition Reset Modernity! we ofer you to do some- thing similar: to reset a few of the instruments that allow you to register some of the confusing signals sent by the epoch. Except what we are trying to recalibrate is not as simple as a compass, but instead the rather obscure principle of projection for mapping the world, namely, modernity. Modernity was a way to diferentiate past and future, north and south, progress and regress, radical and con- servative. However, at a time of profound ecological mutation, such a compass is running in wild circles with- out ofering much orientation anymore. This is why it is time for a reset. Let’s pause for a while, follow a procedure and search for diferent sensors that could allow us to recalibrate our detectors, our instru- ments, to feel anew where we are and where we might wish to go. No guarantee, of course: this is an experiment, a thought experiment, a Gedankenausstellung. HOW TO USE THIS FIELD BOOK This feld book will be your companion throughout your visit. The path through the show is divided into six procedures, each allowing for a partial reset. -

BAM/PFA Program Guide

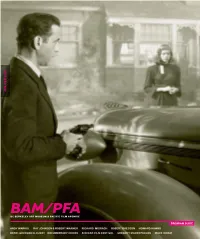

B 2012 B E N/F A J UC BERKELEY ART MUSEum & PacIFIC FILM ARCHIVE PROGRAM GUIDE AnDY WARHOL RAY JOHNSON & ROBERT WARNER RICHARD MISRACH rOBERT BRESSON hOWARD HAWKS HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOt dOCUMENTARY VOICES aFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL GREGORY MARKOPOULOS mARK ISHAM BAM/PFA EXHIBITIONS & FILM SERIES The ReaDinG room P. 4 ANDY Warhol: PolaroiDS / MATRIX 240 P. 5 Tables OF Content: Ray Johnson anD Robert Warner Bob Box ArchiVE / MATRIX 241 P. 6 Abstract Expressionisms: PaintinGS anD DrawinGS from the collection P. 7 Himalayan PilGrimaGE: Journey to the LanD of Snows P. 8 SilKE Otto-Knapp: A liGht in the moon / MATRIX 239 P. 8 Sun WorKS P. 9 1 1991: The OAKlanD-BerKeley Fire Aftermath, PhotoGraphs by RicharD Misrach P. 9 RicharD Misrach: PhotoGraphs from the Collection State of MinD: New California Art circa 1970 P. 10 THOM FaulDers: BAMscape Henri-GeorGes ClouZot: The Cinema of Disenchantment P. 12 Film 50: History of Cinema, Film anD the Other Arts P. 14 BehinD the Scenes: The Art anD Craft of Cinema Composer MARK Isham P. 15 African film festiVal 2012 P. 16 ScreenaGers: 14th Annual Bay Area HIGH School Film anD ViDeo FestiVal P. 17 HowarD HawKS: The Measure of Man P. 18 Austere Perfectionism: The Films of Robert Bresson P. 21 Documentary Voices P. 24 SeconDS of Eternity: The Films of GreGory J. MarKopoulos P. 25 DiZZY HeiGhts: Silent Cinema anD Life in the Air P. 26 Cover GET MORE The Big Sleep, 3.13.12. See Hawks series, p. 18. Want the latest program updates and event reminders in your inbox? Sign up to receive our monthly e-newsletter, weekly film update, 1. -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

The Austere Cinema Of

'SAtti:4110--*. Control and Redemption The Austere Cinema of The Bresson Project is one of the most Jean—Luc Godard says, "Robert Bresson is comprehensive retrospectives undertaken by French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian Cinematheque Ontario. Robert Bresson, now novel and Mozart German music." Yet few of in his early 90s, is described by many critics as Bresson's films are available in any form in the world's greatest living filmmaker. Starting North America and little has been written on with what he considers to be his first film, Les him in English. Accompanying the new series Anges du peche in 1943, Bresson made 13 of 35mm prints by Cinematheque Ontario feature—length films in 40 years. (An earlier for The Bresson Project, is Robert Bresson, a comedy, Les Affaires publiques, filmed in 1935, 600—page collection of essays in English from was considered lost until its discovery in 1987 writer/critics such as Andre Bazin, Susan at La Cinematheque Francaise.) Although Sontag, Alberto Moravia, Jonathan Rosenbaum perhaps not as prodigious as the output from and Rene Predal. Following its debut showing other directors, Bresson's body of work, with at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto last fall, all its passionate austerity, has had an The Bresson Project travels to more than an inestimable influence on the history of cinema. dozen centres across North America this year. T ravelling across central France this route more times than I can recall, toward Lyon, as you near Bromont- more often than not on the way to Lamothe, the spare hillside village Robert the Cannes Film Festival. -

Circ Cine Ve 03-2006

(r.e.) Che ne sarà di Venezia? Nei giorni in cui Veltroni e i suoi sodali illustravano l’allettante menù della prossima Festa romana del cinema, in programma ad ottobre, un provvidenziale torrente di nominations all’Oscar, piovute sui film del- l’edizione 2005, consentiva ai vertici della Fondazione veneziana di tirare un sospiro di sollievo. Del tipo: visto che la qua- lità paga? Che Venezia è sempre Venezia? Che l’arte siamo noi? È oltretutto ben possibile che le candidature vadano a tra- mutarsi in un profluvio di belle statuine, consegnando la competizione lidense ai fasti della Serenissima (Mostra) Trionfante. Bene, benissimo, anzi male, perché la più che legittima (e comprensibile, e condivisibile) soddisfazione per l’auspicato successo dei vari Brokeback Mountain, Good Night, and Good Luck!, Bestia nel cuore potrebbe dar luogo ad un entusiasmo, come dire, fuorviante. In che senso? Ma nel senso che con o senza i prestigiosi riconoscimenti dell’Academy Awards i problemi di Venezia, anche alla luce della concorrenza romana, rimangono. E non paiono risol- vibili d’ufficio con presunti schematismi estetici vecchi già ai tempi del buon Chiarini e magari indigesti allo stesso Marco Müller (l’arte di qua, la merce di là: e il fascinoso trash dove lo mettiamo?), con il ricorso a longevità anagrafiche che sem- mai dovrebbero preoccupare (il primo festival, certo, ma anche il più vecchio), con fughe progettuali in avanti tanto ecu- menicamente condivise quanto finanziariamente improbabili e, qualora possibili, comunque opinabili (il nuovo -

The Austerity Campaign That Never Ended

Decide which new car to buy NYTimes: Home - Site Index - Archive - Help Welcome, trondsen - Member Center - Log Out Go to a Section Search: All of Movies DVD Showtimes & Tickets Search by Movie Title: The Austerity Campaign That Never Ended And/Or by ZIP Code: By TERRENCE RAFFERTY Published: July 4, 2004 T is more or less compulsory — see Page 79 of the official movie critic's handbook — to describe the works of the French filmmaker Robert Bresson as austere, which is not the sort of praise that sets off stampedes to the box office, even in France. In 1965, Susan Sontag wrote: "Bresson is now firmly labeled as an esoteric director. He has never had the attention of the art house audience that flocks to Buñuel, Bergman, Fellini — though he is a far greater director than these." And that was in his (relative) heyday: he had at that point made 6 of his 13 films, including his four best — "Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne" (1945), "The Diary of a Country Priest" (1951), "A Man Escaped" (1956) and "Pickpocket" (1959). Those pictures, it turns out, were about as audience-friendly as he ever got, and, probably, as he ever wanted to be. Now that Bresson's films are finally beginning to trickle out on DVD, a new Museum of Modern Art generation will have its chance to be daunted by this imperious, stubbornly François Leterrier as a condemned uningratiating body of work, and while I wouldn't suggest that the two most recent Frenchman in a Nazi prison in releases, "A Man Escaped" and "Lancelot of the Lake" (1974), answer to any Robert Bresson's "A Man Escaped." reasonable definition of fun, they are, if you surrender to their inexorable rhythm and the rigorous perversities of their style, utterly compelling. -

Robert Bresson: Pickpocket Besetzung: Michel: Martin Lassalle

Robert Bresson: Pickpocket Besetzung: Michel: Martin Lassalle Jeanne: Marika Green Jacques: Pierre Leymarie Inspector: Jean Pelegri Thief: Kassagi Michel's mother: Dolly Scal Regie: Robert Bresson Buch: Robert Bresson Kamera: L.H.Burel Inhalt : Paris. Michel ist der Ansicht, dass es bestimmten Menschen erlaubt ist zu stehlen um sich am Leben zu halten und zu entfalten. So treibt ihn sein Hochmut dazu Taschendieb zu werden. Diese Ansicht vertritt er auch vor einem Kommissar, der wiederum ihm klarmachen will, das man irgendwann ihn dieser Welt des Stehlens gefangen ist. Zudem hält ihn sein Verhalten von Jeanne fern, zu der er sich hingezogen fühlt. Als seine Komplizen gefasst werden flieht er aus Paris. Zwei Jahre später kehrt er zurück. Von nun an möchte er Jeanne, die mittlerweile ein Kind hat helfen und arbeitet. Doch schließlich kann er der Versuchung nicht widerstehen und klaut erneut. Dabei wird er jedoch überführt. Im Gefängnis kommt ihm schließlich die Erkenntnis, dass Jeanne seine Rettung ist und entfaltet die Liebe zu ihr. Robert Bresson (1901- 1999) Filmographie: Les Affaires publiques (1934) Les Anges du péché (1943) Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) Journal d'un curé de campagne (1950) Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut (1956) . Pickpocket (1959) Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc (1962) Au hasard Balthazar (1966) Mouchette (1967) Une femme douce (1969) Quatre nuits d'un rêveur (1971) Lancelot du Lac (1974) Le Diable probablement (1977) L'Argent (1983) Bresson bringt schon früh seinen eigenen Stil in seine Filme. Karge Bilder, immer nah an der Figur.