The Films of Robert Bresson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

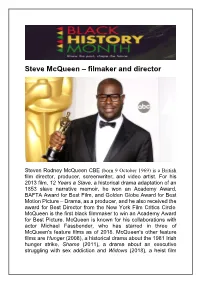

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

El Último Cine

Cartel alemán de Estambul 65 (Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, 1965). Bilbao (Bigas Luna, 1978) SuscripciónSuscripción a la a alertala alerta del del programa programa mensual mensual del del cine cine Doré Doré en: en: http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO Ciclos en preparación: Marzo: William Wellman (y II) CiclosAño enDual preparación: España-Japón 3XDOC Febrero:Ellas crean: Nueve cineastas argentinas Muestra de cine filipino (y II) MuestraRecuerdo de cinede: Jesúsbúlgaro Franco, Alfredo Landa, Lolita Sevilla … CasaCentenario Asia presenta: de Rafael ‘El últimoGil (y II) cine iraní’ RecuerdoJirí Menzel de Maureen O´Hara Mikhail Romm Jirí Menzel Brian de Palma Alberto Lattuada Alberto Lattuada Luc Moullet GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE ENERO 2016 Centenario de Harold Lloyd Robert Bresson Recuerdo de Vicente Aranda Costa-Gavras Muestra de cine filipino Muestra de cine palestino (y II) Muestra de cine rumano (y II) Costa-Gavras Mike de Leon rodando Itim (1976) Agradecimientos enero 2016: A Contracorriente Films, Barcelona; Antonio Isasi Jr., Barcelona; Cinemateca Portuguesa, Lisboa; Film Development Council of the Philippines (Briccio Santos, presidente, y Teodoro Granados, director ejecutivo), Makati; Flat Cinema, Madrid; Gaumont, Harold Lloyd Entertainment, Inc. (Sara Juárez), Los Ángeles; Instituto Cultural Rumano de Madrid (Ioana Anghel, Ovidiu Miron); Lola Films, Madrid; Multivideo S.L, Madrid; Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum (Regina Schlagnitweit ), Viena; Plataforma de Divulgación UCM (Ricardo Jimeno y José Antonio Jiménez de las Heras), Madrid; Tamasa Distribu- tion, París; Universal Pictures; Video Mercury, Madrid; Warner Bros. Pictures int. -

Directing the Narrative Shot Design

DIRECTING THE NARRATIVE and SHOT DESIGN The Art and Craft of Directing by Lubomir Kocka Series in Cinema and Culture © Lubomir Kocka 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933406 ISBN: 978-1-62273-288-3 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. CONTENTS PREFACE v PART I: DIRECTORIAL CONCEPTS 1 CHAPTER 1: DIRECTOR 1 CHAPTER 2: VISUAL CONCEPT 9 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPT OF VISUAL UNITS 23 CHAPTER 4: MANIPULATING FILM TIME 37 CHAPTER 5: CONTROLLING SPACE 43 CHAPTER 6: BLOCKING STRATEGIES 59 CHAPTER 7: MULTIPLE-CHARACTER SCENE 79 CHAPTER 8: DEMYSTIFYING THE 180-DEGREE RULE – CROSSING THE LINE 91 CHAPTER 9: CONCEPT OF CHARACTER PERSPECTIVE 119 CHAPTER 10: CONCEPT OF STORYTELLER’S PERSPECTIVE 187 CHAPTER 11: EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION/ EMOTIONAL DESIGN 193 CHAPTER 12: PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL REGULARITIES IN LEFT-RIGHT/RIGHT-LEFT ORIENTATION 199 CHAPTER 13: DIRECTORIAL-DRAMATURGICAL ANALYSIS 229 CHAPTER 14: DIRECTOR’S BOOK 237 CHAPTER 15: PREVISUALIZATION 249 PART II: STUDIOS – DIRECTING EXERCISES 253 CHAPTER 16: I. -

Pdf-Collections-.Pdf

1 Directors p.3 Thematic Collections p.21 Charles Chaplin • Abbas Kiarostami p.4/5 Highlights from Lobster Films p.22 François Truffaut • David Lynch p.6/7 The RKO Collection p.23 Robert Bresson • Krzysztof Kieslowski p.8/9 The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew p.24 D.W. Griffith • Sergei Eisenstein p.10/11 Yiddish Collection p.25 Olivier Assayas • Alain Resnais p.12/13 Themes p.26 Jia Zhangke • Gus Van Sant p.14/15 — Michael Haneke • Xavier Dolan p.16/17 Buster Keaton • Claude Chabrol p.18/19 Actors p.31 Directors CHARLES CHAPLIN THE COMPLETE COLLECTION AVAILABLE IN 2K “A sort of Adam, from whom we are all descended...there were two aspects of — his personality: the vagabond, but also the solitary aristocrat, the prophet, the The Kid • Modern Times • A King in New York • City Lights • The Circus priest and the poet” The Gold Rush • Monsieur Verdoux • The Great Dictator • Limelight FEDERICO FELLINI A Woman of Paris • The Chaplin Revue — Also available: short films from the First National and Keystone collections (in 2k and HD respectively) • Documentaries Charles Chaplin: the Legend of a Century (90’ & 2 x 45’) • Chaplin Today series (10 x 26’) • Charlie Chaplin’s ABC (34’) 4 ABBas KIAROSTAMI NEWLY RESTORED In 2K OR 4K “Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema” — MARTIN SCORSESE Like Someone in Love (in 2k) • Certified Copy (in 2k) • Taste of Cherry (soon in 4k) Shirin (in 2k) • The Wind Will Carry Us (soon in 4k) • Through the Olive Trees (soon in 4k) Ten & 10 on Ten (soon in 4k) • Five (soon in 2k) • ABC Africa (soon -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

The Austerity Campaign That Never Ended

Decide which new car to buy NYTimes: Home - Site Index - Archive - Help Welcome, trondsen - Member Center - Log Out Go to a Section Search: All of Movies DVD Showtimes & Tickets Search by Movie Title: The Austerity Campaign That Never Ended And/Or by ZIP Code: By TERRENCE RAFFERTY Published: July 4, 2004 T is more or less compulsory — see Page 79 of the official movie critic's handbook — to describe the works of the French filmmaker Robert Bresson as austere, which is not the sort of praise that sets off stampedes to the box office, even in France. In 1965, Susan Sontag wrote: "Bresson is now firmly labeled as an esoteric director. He has never had the attention of the art house audience that flocks to Buñuel, Bergman, Fellini — though he is a far greater director than these." And that was in his (relative) heyday: he had at that point made 6 of his 13 films, including his four best — "Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne" (1945), "The Diary of a Country Priest" (1951), "A Man Escaped" (1956) and "Pickpocket" (1959). Those pictures, it turns out, were about as audience-friendly as he ever got, and, probably, as he ever wanted to be. Now that Bresson's films are finally beginning to trickle out on DVD, a new Museum of Modern Art generation will have its chance to be daunted by this imperious, stubbornly François Leterrier as a condemned uningratiating body of work, and while I wouldn't suggest that the two most recent Frenchman in a Nazi prison in releases, "A Man Escaped" and "Lancelot of the Lake" (1974), answer to any Robert Bresson's "A Man Escaped." reasonable definition of fun, they are, if you surrender to their inexorable rhythm and the rigorous perversities of their style, utterly compelling. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

300 Greatest Films 4 Black Copy

The goal in this compilation was to determine film history's definitive creme de la creme. The titles considered to be the greatest of the great from around the world and throughout the history of film. So, after an in-depth analysis of respected critics and publications from around the globe, cross-referenced and tweaked to arrive at the ranking of films representing, we believe, the greatest cinema can offer. Browse, contemplate, and enjoy. Check off all the films you have seen 1 Citizen Kane 1941 USA 26 The 400 Blows 1959 France 51 Au Hasard Balthazar 1966 France 76 L.A. Confidential 1997 USA 2 Vertigo 1958 USA 27 Satantango 1994 Hungary 52 Andrei Rublev 1966 USSR 77 Modern Times 1936 USA 3 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 UK 28 Raging Bull 1980 USA 53 All About Eve 1950 USA 78 Mr Hulot's Holiday 1952 France 4 The Rules of the Game 1939 France 29 L'Atalante 1934 France 54 Sunset Boulevard 1950 USA 79 Wings of Desire 1978 France 5 Seven Samurai 1954 Japan 30 Annie Hall 1977 USA 55 The Turin Horse 2011 Hungary 80 Ikiru 1952 Japan 6 The Godfather 1972 USA 31 Persona 1966 Sweden 56 Jules and Jim 1962 France 81 The Apartment 1960 USA 7 Apocalypse Now 1979 USA 32 Man With a Movie Camera 1929 USSR 57 Double Indemnity 1944 USA 82 Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie 1972 France 8 Tokyo Story 1953 Japan 33 E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 1982 USA 58 Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963 France 83 The Seventh Seal 1957 Sweden 9 Taxi Driver 1976 USA 34 Star Wars Episode IV 1977 USA 59 Belle De Jour 1967 France 84 Wild Strawberries 1957 Sweden 10 Casablanca 1942 USA 35 -

This Is a List of the Titles and Classmarks of the Library's DVD Collection As of November 2018 for Quick Reference. the Colle

St John’s College Library DVD Collection This is a list of the titles and classmarks of the Library’s DVD collection as of November 2018 for quick reference. The collection can be browsed in the AV Room on the First Floor, and current availability can be found via the online catalogue. The collection is constantly being updated so for the most up to date titles, please search the online catalogue. The first section of this guide is organised alphabetically by title. The second section is organised by language/country. Title Call Number 8 1/2 DVD ITA.ott.fel 8 1/2 DVD ITA.ott.fel 36 DVD FRE.tre.mar 1871 DVD ENG.eig.mcm 1984 DVD ENG.nin.rad 2046 DVD CHI.twe.won 10 Cloverfield Lane DVD ENG.ten.tra 10 things I hate about you DVD ENG.ten.jun 1000 Dollari sul nero = Blood at Sundown DVD ITA.mil.sir 10000 dollari per un massacro = $10000 blood money DVD ITA.die.gue 12 years a slave DVD ENG.twe.mcq 20,000 days on Earth DVD ENG.twe.for 2001 : a space odyssey DVD ENG.two.kub 28 days later DVD ENG.twe.boy 2point4 children the complete series three DVD ENG.two.mar 3 godfathers DVD ENG.thr.for 45 years DVD ENG.for.hai 47 ronin DVD JAP.shi.ich 50 years of the Cuban revolution DVD SPA.fif.cub 50 years of the Cuban revolution DVD SPA.fif.cub 50 years of the Cuban revolution DVD SPA.fif.cub 50 years of the Cuban revolution DVD SPA.fif.cub 60s collection DVD FRE.god.god 8 women DVD FRE.hui.ozo A beautiful mind DVD ENG.bea.how A bit of Fry and Laurie the complete fourth series DVD ENG.bit.spi A bronx tale DVD ENG.bro.den A bullet for the general DVD ITA.qui.dam A Christmas tale a film by Arnaud Desplechin.