1 WATER EDUCATION in PARAGUAY by Amanda Justine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Services Policy Review of Paraguay

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT SERVICES POLICY REVIEW PARAGUAY UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT SERVICES POLICY REVIEW PARAGUAY ii SERVICES POLICY REVIEW OF PARAGUAY NOTE The symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat or of the government of Paraguay. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat. This publication has been edited externally. For further information on the Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch and its activities, please contact: Ms. Mina MASHAYEKHI Head Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch Division of International Trade in Goods and Services, and Commodities Tel: +41 22 917 56 40 Fax: +41 22 917 00 44 www.unctad.org/tradenegotiations UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2014/2 © Copyright United Nations 2014 All rights reserved. Printed in Switzerland ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication presents the result of a Services Policy Review (SPR) undertaken by the government of Paraguay in collaboration with UNCTAD. -

Paraguay Mennonites: Immigrants, Citizens, Hosts

Mennonite Central Committee Peace Office Publication January –March 2009 Volume 39, Number 1 Paraguay Mennonites: Immigrants, Citizens, Hosts IN THIS ISSUE Introduction 3 Mennonites In Paraguay: by Daryl Yoder-Bontrager A Brief History by Edgar Stoesz n July of this year, people who are part Paraguay was appropriate for Mennonites Iof the Anabaptist tradition will gather in in other ways as well. A somewhat isolated, 6 A Letter from Paraguay: Asunción, Paraguay from all over the world land-locked country in the middle of the The 2008 Elections to celebrate the 15th global assembly of Southern Cone, the southern triangle of by Alfred Neufeld Mennonite World Conference. The assembly South America, Paraguay contained vast will be hosted jointly by the 8 Paraguayan tracts of sparsely populated lands in its 9 Hopes and Plans for the MWC member churches. In anticipation northwest Chaco area. The Chaco region, 2009 Mennonite World of that event, this issue of Peace Office shared with Bolivia and Argentina, is Conference Assembly 15 Newsletter offers some beginning glimpses famous for its climatic extremes. The coun - by Carmen Epp into the people and issues of Paraguay. try had long since merged Spanish-speaking and Guarani-speaking cultures. Today Span - 11 Ernst Bergen, Jumping into Almost anywhere in Paraguay at nearly any ish and Guarani, the language of the domi - Empty Space time of day one can find Paraguayans clus - nant indigenous group, are both official reviewed by Alain Epp Weaver tered in little groups drinking tereré, a cold languages. Moving to Paraguay seemed a tea, sipped from a metal straw stuck into win/win situation. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Bilingual Education in Paraguay Hiroshi Ito

Ito Multilingual Education 2012, 2:6 http://www.multilingual-education.com/content/2/1/6 RESEARCH Open Access With Spanish, Guaraní lives: a sociolinguistic analysis of bilingual education in Paraguay Hiroshi Ito Abstract Through interviews with Paraguayan parents, teachers, intellectuals, and policy makers, this paper examines why the implementation of Guaraní-Spanish bilingual education has been a struggle in Paraguay. The findings of the research include: 1) ideological and attitudinal gaps toward Guaraní and Spanish between the political level (i.e., policy makers and intellectuals) and the operational level (i.e., parents and teachers); 2) insufficient and/or inadequate Guaraní-Spanish bilingual teacher training; and 3) the different interpretations and uses of the terms pure Guaraní (also called academic Guaraní) and Jopará (i.e., colloquial Guaraní with mixed elements of Spanish) between policy makers and intellectuals, and the subsequent issue of standardizing Guaraní that arises from these mixed interpretations. Suggestions are made to carve out a space wherein we might imagine an adequate implementation of bilingual education. Keywords: Bilingual education policy, Language ideologies and attitudes, Diglossia, Guaraní, Paraguay Introduction children to learn Spanish. Yet, without Guaraní in the The sociopolitical linguistic landscape in Paraguay is classroom, it is difficult for Guaraní-speaking children to unique, complex, and even contradictory. Unlike many learn Spanish and other academic content taught in Spanish languages -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title ¿Nuestro guaraní? Language Ideologies, Identity, and Guaraní Instruction in Asunción, Paraguay / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9k50224n Author Lang, Nora Walsh Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ¿Nuestro guaraní? Language Ideologies, Identity, and Guaraní Instruction in Asunción, Paraguay A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies by Nora Walsh Lang Committee in charge: Professor Olga Vásquez, Chair Professor Alison Wishard Guerra Professor Christine Hunefeldt 2014 Copyright Nora Walsh Lang, 2014 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nora Walsh Lang is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To all of the members of Ruffinelli family, for opening up their hearts and homes, over and over and again. iv EPIGRAPH We must understand that they (children) are multidimensional beings, formed and being formed within contexts of discourses and histories. What we should be about is big people helping little people to become big people, theorizing about the practices that nurture and support. -Norma González (2001) I am my language: Discourses of women & children in the borderlands. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………………………………...iii -

A Selection of Flowering Shrubs and Trees for Color in Miami-Dade Landscapes

A Selection of Flowering Shrubs and Trees for Color in Miami-Dade Landscapes If no ‘Season for Flowering’ is indicated, flowering occurs periodically throughout the year (usually less so in cooler weather). If water needs are not shown (see key below: drought tolerance/need for moist soil), provide supplemental water once per week to established plants in prolonged hot dry conditions; reduce frequency during cooler winter weather. KEY: sm.tr - Small tree; lg.tr - Large tree; shr – Shrub; cl.sh - Climbing shrub (requires some support); m - Moist soil (limited drought tolerance); dr - Drought Tolerant; fs - Full sun; ss - Some shade. Shrub/Tree Season for Flowering WHITE Beaumontia grandiflora (cl.sh; fs) -> winter (Herald’s Trumpet)1 Brunfelsia jamaicensis (shr; ss; m) -> late fall – winter (Jamaica Raintree)1 Ceiba insignis (lg.tr; fs; dr) -> fall (White Silk Floss Tree) Cordia boissieri (sm.tr; fs; dr) (Texas white olive)2 Dombeya burgessiae (shr; fs) cream – pale pink -> late fall – winter (Apple Blossom, Pink Pear Blossom)1 Eranthemum nigrum (see E. pulchellum below) (Ebony) Euphorbia leucophylla (shr/sm.tr; fs) white/pink -> winter (Little Christmas Tree, Pascuita)1, 2 Fagrea ceylanica (shr/sm.tr; fs/ss; dr) (Ceylon Fagrea) 1,2 Gardenia taitensis (shr/sm.tr; fs; dr) (Tahitian Gardenia)1,2 Jacquinia arborea, J. keyensis (sm.tr/shr; fs; dr) -> spring – summer (Bracelet Wood)1 (Joewood) 1, 2 1 Fragrant 2 Adapts especially well to limestone Kopsia pruniformis (shr/sm.tr; fs/ss.)♣ (Java plum) Mandevilla boliviensis (cl.sh/ss) -> spring -

JAPANESE IMMIGRANTS ABROAD by John B

JAPANESE IMMIGRANTS ABROAD by John B. Cornell and Robert J. Smith Introduction Our intent here is to review research completed to date on our subject and to call attention to topics which seem particularly promising for future investigation. We have limited our concern to research on Japanese in the Americas and Hawaii, feeling that materials on Japanese in other areas are too fugitive or the issues they concern too parochial to justify inclusion in this brief review. Migration from Japan began in 1868, the year of the Restoration. Al- though Japan strove to resettle large numbers of excess proletarians in Manchukuo and other areas under her political control in the interwar period, the most successful, lasting and best documented migrations were to other regions of the world and seem to bear no relation to the Empire's colonial ambitions. Well above a million, and possibly five million, Japa- nese went abroad during this period for reasons other than tourism and governmental foreign service (Ichihashi 1932: 12; Ota 1968: 1). Foreign reaction to the image of Japan presented by immigrants abroad has tended to be mixed and in general far less favorable than that produced by Jap- anese achievements in the arts, letters, technology, and scholarship. The body of literature on emigration and the Japanese abroad is vast, but it is uneven in quality and displays little thematic consistency. One of its promi- nent characteristics is a pulse-like pattern over time as the intensity of scholarly interest in migration rose and fell according to the intensity of concern felt by receiving nations over strategies of accepting and exporting immigrants and over the treatment of resident Japanese minorities. -

Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay

Pedagogical Research 2021, 6(3), em0096 e-ISSN: 2468-4929 https://www.pedagogicalresearch.com Research Article OPEN ACCESS Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay Marcelo de Oliveira Dias 1* 1 Universidade Federal Fluminense, BRAZIL *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Citation: Dias, M. d. O. (2021). Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay. Pedagogical Research, 6(3), em0096. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/10950 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 21 Sep. 2020 The construction of the National Common Curricular Base (NCCB) for the area of Mathematics and its High School Accepted: 18 Mar. 2021 Technologies in Brazil and the last update of the Mathematics Program for High School in Paraguay are prescribed curriculum documents in force for the teaching of Mathematics in these countries. The construction of each one of them exposed intense political elements and has been a constant target of conflicts and tensions in these countries. The policy cycle approach, established by sociologist Stephen J. Ball and collaborators, has usually been applied by curriculum policy researchers, as well as from other sectors. Therefore, it has been configured in an important methodological bias for the understanding of the documents’ approval processes from the contexts of production and influence, as well as the standards that guided this construction and the ideological constraints that emanate from the involvement of multilateral organisms. In order to achieve this objective, this article presents a comparative analysis of documents in specific circumstances during the processes of the recent reforms of the prescribed documents for mathematical learning in Brazil and Paraguay. -

Paraguay Investment Guide 2019-2020 Summary

PARAGUAY INVESTMENT GUIDE 2019-2020 SUMMARY Investments and Exports Network of paraguay - REDIEX EDUCATION AND HEALTH IN COUNTRY TRAITS LEGAL FRAMEWORK PARAGUAY 1.1. Socio-economic, political and 4.1. Tax Regime 7.1. Education Services geographical profile 4.2. Labor System 7.2. Professional and Occupational 1.2. Land and basic infrastructure 4.3. Occupational health and safety Training Av. Mcal. López 3333 esq. Dr. Weiss 1.3. Service Infrastructure policies of covid-19 7.3. Health Services Asunción - Villa Morra 1.4. Corporate structure 4.4. Immigration Laws 1 4 7 Paraguay. Page. 9 1.5. Contractual relations between Page. 101 4.5. Intellectual Property Page. 151 Tel.: +595 21 616 3028 +595 21 616 3006 foreign companies and their 4.6. Summary of procedures and [email protected] - www.rediex.gov.py representatives in Paraguay requirements to request the foreign 1.6. Economy investor’s certification via SUACE Edition and General Coordination 4.7. Environmental legislation Paraguay Brazil Chamber of Commerce REAL ESTATE MARKET MAJOR INVESTMENT SECTORS IMPORT AND EXPORT OF GOODS 8.1. Procedure for real estate purchase 8.2. Land acquisition by foreigners 2.1. General Information 5.1. Regulatory framework for interna- Av. Aviadores del Chaco 2050, Complejo World Trade Center Asunción, 2.2. Countries investing in Paraguay tional trade Torre 1, Piso 14 Asunción - Paraguay 2.3. Investment sectors 5.2. Customs 8 Page. 157 Tel.: +595 21 612 - 614 | +595 21 614 - 901 2.4. Investments 5.3. Customs broker [email protected] - www.ccpb.org.py 2 5 5.4. -

Development of Allometric Equations for Tree Biomass in Forest Ecosystems in Paraguay

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279917200 Development of Allometric Equations for Tree Biomass in Forest Ecosystems in Paraguay Article in Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly · July 2015 DOI: 10.6090/jarq.49.281 CITATIONS READS 13 423 12 authors, including: Tamotsu Sato Lidia Pérez de Molas Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute Universidad Nacional de Asunción 69 PUBLICATIONS 645 CITATIONS 22 PUBLICATIONS 38 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Yukako Monda Mirtha Vera De Ortiz Kyoto University Universidad Nacional de Asunción 14 PUBLICATIONS 178 CITATIONS 10 PUBLICATIONS 35 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Manejo de Recursos Naturales View project Relationship between aboveground biomass and measures of structure and species diversity in tropical forests of Vietnam View project All content following this page was uploaded by Tamotsu Sato on 24 March 2021. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. JARQ 49 (3), 281 - 291 (2015) http://www.jircas.affrc.go.jp Development of Allometric Equations for Tree Biomass in Forest Ecosystems in Paraguay Tamotsu SATO1*, Masahiro SAITO2, Delia RAMÍREZ3, Lidia F. PÉREZ DE MOLAS3, Jumpei TORIYAMA2, Yukako MONDA2, Yoshiyuki KIYONO4, Emigdio HEREBIA3, Nora DUBIE5, Edgardo DURÉ VERA5, Jorge David RAMIREZ ORTEGA5 and Mirtha VERA DE ORTIZ3 1 Department of Forest Vegetation, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute -

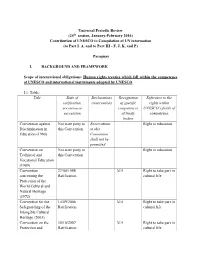

Universal Periodic Reporting

Universal Periodic Review (24th session, January-February 2016) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN information (to Part I. A. and to Part III - F, J, K, and P) Paraguay I. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK Scope of international obligations: Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Title Date of Declarations Recognition Reference to the ratification, /reservations of specific rights within accession or competences UNESCO’s fields of succession of treaty competence bodies Convention against Not state party to Reservations Right to education Discrimination in this Convention to this Education (1960) Convention shall not be permitted Convention on Not state party to Right to education Technical and this Convention Vocational Education (1989) Convention 27/04/1988 N/A Right to take part in concerning the Ratification cultural life Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) Convention for the 14/09/2006 N/A Right to take part in Safeguarding of the Ratification cultural life Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) Convention on the 30/10/2007 N/A Right to take part in Protection and Ratification cultural life 2 Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) II. Input to Part III. Implementation of international human rights obligations, taking into account applicable international humanitarian law to items F, J, K, and P Right to education 1. NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK 1.1. Constitutional Framework1: 1. The right to education is provided in the Constitution adopted on 20 June 19922. Article 73 of the Constitution defines the right to education as the “right to a comprehensive, permanent educational system, conceived as a system and a process to be realized within the cultural context of the community”. -

From Japonés to Nikkei: the Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese

From japonés to Nikkei: The Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese Descent by Eszter Rácz Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Szabolcs Pogonyi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2019 Abstract This thesis investigates what defines the identity of third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians and what is the current definition of Nikkei ethnic belonging on personal as well as institutional level. I look at the identity formation processes of Peruvians with ethnic Japanese background in light of the strong attachment to Japan as an imagined homeland, the troubled history of anti-Japanese discrimination in Peru and US internment of Japanese Peruvians during World War II, the consolidation of Japanese as a high-status minority, and ethnic return migration to Japan from 1990. Ethnicity has been assumed to be the cornerstone of identity in both Latin America where high sensitivity for racial differences results in intergenerational categorization and Japan where the essence of Japaneseness is assumed to run through one’s veins and passed on to further generations even if they were born and raised abroad. However when ethnic returnees arrived to Japan they had to realize that they were not Japanese by Japanese standards and chose to redefine themselves, in the case of Japanese Peruvians as Nikkei. I aim to explore the contents of the Japanese Peruvian definition of Nikkei by looking at existing literature and conducting video interviews through Skype and Messenger with third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians. I look into what are their personal experiences as Nikkei, what changes do they recognize as the consequence of ethnic return migration, whether ethnicity has remained the most relevant in forming social relations, and what do they think about Japan now that return migration is virtually ended and the visa that allowed preferential access to Japanese descendants is not likely to be extended to further generations. -

Paraguay Region: Latin America and the Caribbean Income Group: Lower Middle Income Source for Region and Income Groupings: World Bank 2018

Paraguay Region: Latin America and the Caribbean Income Group: Lower Middle Income Source for region and income groupings: World Bank 2018 National Education Profile 2018 Update OVERVIEW In Paraguay, the academic year begins in February and ends in December, and the official primary school entrance age is 6. The system is structured so that the primary school cycle lasts 6 years, lower secondary lasts 3 years, and upper secondary lasts 3 years. Paraguay has a total of 1,339,000 pupils enrolled in primary and secondary education. Of these pupils, about 727,000 (54%) are enrolled in primary education. Figure 3 shows the highest level of education reached by youth ages 15-24 in Paraguay. Although youth in this age group may still be in school and working towards their educational goals, it is notable that approximately 2% of youth have no formal education and 7% of youth have attained at most incomplete primary education, meaning that in total 9% of 15-24 year olds have not completed primary education in Paraguay. FIG 1. EDUCATION SYSTEM FIG 2. NUMBER OF PUPILS BY SCHOOL LEVEL FIG 3. EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, YOUTH (IN 1000S) AGES 15-24 School Entrance Age: Primary Primary school - Age 6 Incomplete No Education7% Upper Post- 2% Primary Complete Secondary Secondary 7% Duration and Official Ages for School Cycle: 283 26% Primary : 6 years - Ages 6 - 11 Lower secondary : 3 years - Ages 12 - 14 Upper secondary : 3 years - Ages 15 - 17 Primary 727 Academic Calendar: Lower Secondary Secondary Complete 329 15% Secondary Starting month : February Incomplete 43% Ending month : December Data source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics Data Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2016 Data source: EPDC extraction of MICS dataset 2016 SCHOOL PARTICIPATION AND EFFICIENCY The percentage of out of school children in a country shows what proportion of children are not currently participating in the education system and who are, therefore, missing out on the benefits of school.