UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Services Policy Review of Paraguay

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT SERVICES POLICY REVIEW PARAGUAY UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT SERVICES POLICY REVIEW PARAGUAY ii SERVICES POLICY REVIEW OF PARAGUAY NOTE The symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat or of the government of Paraguay. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat. This publication has been edited externally. For further information on the Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch and its activities, please contact: Ms. Mina MASHAYEKHI Head Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch Division of International Trade in Goods and Services, and Commodities Tel: +41 22 917 56 40 Fax: +41 22 917 00 44 www.unctad.org/tradenegotiations UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2014/2 © Copyright United Nations 2014 All rights reserved. Printed in Switzerland ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication presents the result of a Services Policy Review (SPR) undertaken by the government of Paraguay in collaboration with UNCTAD. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Bilingual Education in Paraguay Hiroshi Ito

Ito Multilingual Education 2012, 2:6 http://www.multilingual-education.com/content/2/1/6 RESEARCH Open Access With Spanish, Guaraní lives: a sociolinguistic analysis of bilingual education in Paraguay Hiroshi Ito Abstract Through interviews with Paraguayan parents, teachers, intellectuals, and policy makers, this paper examines why the implementation of Guaraní-Spanish bilingual education has been a struggle in Paraguay. The findings of the research include: 1) ideological and attitudinal gaps toward Guaraní and Spanish between the political level (i.e., policy makers and intellectuals) and the operational level (i.e., parents and teachers); 2) insufficient and/or inadequate Guaraní-Spanish bilingual teacher training; and 3) the different interpretations and uses of the terms pure Guaraní (also called academic Guaraní) and Jopará (i.e., colloquial Guaraní with mixed elements of Spanish) between policy makers and intellectuals, and the subsequent issue of standardizing Guaraní that arises from these mixed interpretations. Suggestions are made to carve out a space wherein we might imagine an adequate implementation of bilingual education. Keywords: Bilingual education policy, Language ideologies and attitudes, Diglossia, Guaraní, Paraguay Introduction children to learn Spanish. Yet, without Guaraní in the The sociopolitical linguistic landscape in Paraguay is classroom, it is difficult for Guaraní-speaking children to unique, complex, and even contradictory. Unlike many learn Spanish and other academic content taught in Spanish languages -

1 WATER EDUCATION in PARAGUAY by Amanda Justine

WATER EDUCATION IN PARAGUAY By Amanda Justine Horvath B.S. Ohio Northern University, 2006 A thesis submitted to the University of Colorado Denver in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Environmental Sciences May 2010 1 This thesis for the Master of Science degree by Amanda Justine Horvath has been approved by Bryan Shao-Chang Wee John Wyckoff Jon Barbour Date 2 Horvath, Amanda Justine (Master of Science, Environmental Sciences) Water Education in Paraguay Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Bryan Shao-Chang Wee ABSTRACT The importance of water as a resource is a foundational concept in environmental science that is taught and understood in different ways. Some countries place a greater emphasis on water education than others. This thesis explores the educational system in Paraguay, with a particular focus on environmental education and water. Coupling my work as a Peace Corps/Paraguay Environmental Education Volunteer and my participation with Project WET, a nonprofit organization that specializes in the development of water education activities, I compiled country specific information on the water resources of Paraguay and used this information to adapt 11 Project WET Mexico activities to the Paraguayan classroom. There were many cultural and social factors that were considered in the adaption process, such as language and allotted time for lessons. These activities were then presented in a series of teacher workshops in three different locations to further promote water education in Paraguay. This abstract accurately represents the content of the candidate’s thesis. I recommend its publication. Signed ________________________________ Bryan Shao-Chang Wee 3 DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my parents in gratitude for their support with all my crazy adventures and ideas and also to the people of Paraguay, who opened their homes and hearts to me for over two and a half years. -

Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay

Pedagogical Research 2021, 6(3), em0096 e-ISSN: 2468-4929 https://www.pedagogicalresearch.com Research Article OPEN ACCESS Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay Marcelo de Oliveira Dias 1* 1 Universidade Federal Fluminense, BRAZIL *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Citation: Dias, M. d. O. (2021). Reforms of Mathematics Curriculum Guidelines for Middle Education in Brazil and Paraguay. Pedagogical Research, 6(3), em0096. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/10950 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 21 Sep. 2020 The construction of the National Common Curricular Base (NCCB) for the area of Mathematics and its High School Accepted: 18 Mar. 2021 Technologies in Brazil and the last update of the Mathematics Program for High School in Paraguay are prescribed curriculum documents in force for the teaching of Mathematics in these countries. The construction of each one of them exposed intense political elements and has been a constant target of conflicts and tensions in these countries. The policy cycle approach, established by sociologist Stephen J. Ball and collaborators, has usually been applied by curriculum policy researchers, as well as from other sectors. Therefore, it has been configured in an important methodological bias for the understanding of the documents’ approval processes from the contexts of production and influence, as well as the standards that guided this construction and the ideological constraints that emanate from the involvement of multilateral organisms. In order to achieve this objective, this article presents a comparative analysis of documents in specific circumstances during the processes of the recent reforms of the prescribed documents for mathematical learning in Brazil and Paraguay. -

Universal Periodic Reporting

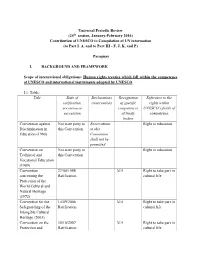

Universal Periodic Review (24th session, January-February 2016) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN information (to Part I. A. and to Part III - F, J, K, and P) Paraguay I. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK Scope of international obligations: Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Title Date of Declarations Recognition Reference to the ratification, /reservations of specific rights within accession or competences UNESCO’s fields of succession of treaty competence bodies Convention against Not state party to Reservations Right to education Discrimination in this Convention to this Education (1960) Convention shall not be permitted Convention on Not state party to Right to education Technical and this Convention Vocational Education (1989) Convention 27/04/1988 N/A Right to take part in concerning the Ratification cultural life Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) Convention for the 14/09/2006 N/A Right to take part in Safeguarding of the Ratification cultural life Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) Convention on the 30/10/2007 N/A Right to take part in Protection and Ratification cultural life 2 Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) II. Input to Part III. Implementation of international human rights obligations, taking into account applicable international humanitarian law to items F, J, K, and P Right to education 1. NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK 1.1. Constitutional Framework1: 1. The right to education is provided in the Constitution adopted on 20 June 19922. Article 73 of the Constitution defines the right to education as the “right to a comprehensive, permanent educational system, conceived as a system and a process to be realized within the cultural context of the community”. -

Paraguay Region: Latin America and the Caribbean Income Group: Lower Middle Income Source for Region and Income Groupings: World Bank 2018

Paraguay Region: Latin America and the Caribbean Income Group: Lower Middle Income Source for region and income groupings: World Bank 2018 National Education Profile 2018 Update OVERVIEW In Paraguay, the academic year begins in February and ends in December, and the official primary school entrance age is 6. The system is structured so that the primary school cycle lasts 6 years, lower secondary lasts 3 years, and upper secondary lasts 3 years. Paraguay has a total of 1,339,000 pupils enrolled in primary and secondary education. Of these pupils, about 727,000 (54%) are enrolled in primary education. Figure 3 shows the highest level of education reached by youth ages 15-24 in Paraguay. Although youth in this age group may still be in school and working towards their educational goals, it is notable that approximately 2% of youth have no formal education and 7% of youth have attained at most incomplete primary education, meaning that in total 9% of 15-24 year olds have not completed primary education in Paraguay. FIG 1. EDUCATION SYSTEM FIG 2. NUMBER OF PUPILS BY SCHOOL LEVEL FIG 3. EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, YOUTH (IN 1000S) AGES 15-24 School Entrance Age: Primary Primary school - Age 6 Incomplete No Education7% Upper Post- 2% Primary Complete Secondary Secondary 7% Duration and Official Ages for School Cycle: 283 26% Primary : 6 years - Ages 6 - 11 Lower secondary : 3 years - Ages 12 - 14 Upper secondary : 3 years - Ages 15 - 17 Primary 727 Academic Calendar: Lower Secondary Secondary Complete 329 15% Secondary Starting month : February Incomplete 43% Ending month : December Data source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics Data Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2016 Data source: EPDC extraction of MICS dataset 2016 SCHOOL PARTICIPATION AND EFFICIENCY The percentage of out of school children in a country shows what proportion of children are not currently participating in the education system and who are, therefore, missing out on the benefits of school. -

Astronomy Education in Paraguay Or on This Document Please Contact the Office of Astronomy for Education ([email protected])

Astronomy Education in Paraguay This overview is part of the project "Astronomy Education Worldwide" of the International Astronomical Union's Office of Astronomy for Education. More information: https://astro4edu.org/worldwide Structure of education: the curriculum is divided into 3 levels, begins with two years of non-obligatory Initial Education (kindergarten) at the ages of 3 or 4, and then continue to Basic School Education at the age of 6 which is obligatory, it is composed of nine grades with an extension of one year each divided into 3 cycles. Then it follows Medium Level (Secondary) which is non obligatory and has an extension of three years, it has two modalities to follow, Science Secondary where students have as a choice different emphasis as Arts, Literature, Social Sciences and Technology, etc. and Technical Secondary with emphasis on Nursing, Computer Science, Constructions, etc. There is as well a level that offers Basic Education to people older than 15 years who have not had access to Basic School Education and the degree is equivalent to it; it has a three-year extension. 18 years old students who haven’t been able to access to secondary have the opportunity to achieve an equivalent degree in a faster way that is summarized in two years. Those twelve years and the alternatives to it are free of charge at state schools, there’s also private schools which charge of fees to students and account for the 10% of the pupils, as well as subsidized schools that are funded in part by the state and the students through the charge of fees and represent the 12% of the pupils. -

The Afro-Paraguayan Community of Cambacuá Introduction Being Black in Paraguay

Micro Study Minority Rights Development& The Afro-Paraguayan Community of Cambacuá Introduction Being black in Paraguay ambacuá is an Afro-Paraguayan community of 300 o be black in Paraguay is to be almost invisible to the rest families (c. 2,000 individuals) located some 15 km to the Tof society. Most Paraguayans are unaware of the existence Ceast of the Paraguayan capital Asunción in the of a black community in Paraguay and assume that any black municipality of Fernando de la Mora. Just over 30 years ago people are Brazilian. Nevertheless, Afro-Paraguayans, despite the community was violently dispossessed of over 90 per cent their lack of numbers and the daily racism to which they are of its land by the Paraguayan state. Since then, in the face of subjected, maintain a distinct identity characterized by a human rights abuses, immense poverty and racial vibrant and continually evolving culture. Since Afro- discrimination, the community has been immersed in a struggle Paraguayans are not included as a separate category within the both to retain its identity and to have its traditional land national census their exact numbers are unknown; however, restored. This is the story of that struggle. along with the indigenous population – who comprise 2 per cent of the population – they are among the most impoverished groups in the country. While the Paraguayan Constitution recognizes the existence of indigenous people – and guarantees them the right to land and the freedom to practise their distinct cultures – Afro-Paraguayans as a separate category are absent from any national legislation, as if it were assumed that black culture either has disappeared, or should do so. -

Indigenous Intercultural Bilingual Education in Latin America

2010/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/29 Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2010 Reaching the marginalized Reaching the unreached: indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America Luis Enrique López 2009 This paper was commissioned by the Education for All Global Monitoring Report as background information to assist in drafting the 2010 report. It has not been edited by the team. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the EFA Global Monitoring Report or to UNESCO. The papers can be cited with the following reference: “Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2010, Reaching the marginalized” For further information, please contact [email protected] López IIBE 2009 Reaching the unreached: indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America Commission Background Study for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2009 Luis Enrique López1 Around the world, it is clear that simply stating that equal opportunities exist for all does not ensure equal participation from all. This is so because complex patterns of discrimination act as powerful obstacles to access. These patterns act both through cultural messages given by society and through personal subordinated attitudes. Therefore if educational opportunities are to reach all groups which are discriminated against, then specific obstacles to access must be identified and programmes organised in response to them. In ICAE (International Council of Adult Education), 2003, Agenda for the Future. Six Years Later. Pp. 16-17. 1. Introduction The paper focuses on the educational situation of the most marginalized children and adolescents in Latin America: those belonging to indigenous homes and communities. -

Determinants of Student Achievements in the Primary Education of Paraguay

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Otter, Thomas; Villalobos Barría, Carlos Working Paper Determinants of student achievements in the primary education of Paraguay IAI Discussion Papers, No. 198 Provided in Cooperation with: Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research, University of Goettingen Suggested Citation: Otter, Thomas; Villalobos Barría, Carlos (2009) : Determinants of student achievements in the primary education of Paraguay, IAI Discussion Papers, No. 198, Georg- August-Universität Göttingen, Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research (IAI), Göttingen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/57338 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

School Infrastructure in Paraguay

A WORLD BANK STUDY School Infrastructure in Paraguay NEEDS, INVESTMENTS, AND COSTS Quentin Wodon School Infrastructure in Paraguay A WORLD BANK STUDY School Infrastructure in Paraguay Needs, Investments, and Costs Quentin Wodon © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 World Bank Studies are published to communicate the results of the Bank’s work to the development com- munity with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally edited texts. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, inter- pretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

Planning Education for Regional Economic Integration: the Case of Paraguay and MERCOSUR

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 362 938 EA 025 110 AUTIOR McGinn, Noel Planning Education for Regional Economic Integration: The Case of Paraguay and MERCOSUR. PUB DATE Mar 93 NOTE llp.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Comparative and International Education Society (Kingston, Jamaica, March 1993). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Economic Development; *Economic Impact; Educational Planning; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Exports; Foreign Countries; Imports; *International Trade IDENTIFIERS *MERCOSUR; *Paraguay; South America ABSTRACT This paper examines the possible impact of MERCOSUR on Paraguay's economic and educational systems. MERCOSUR is a trade agreement among Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, under which terms all import tariffs among the countries will be eliminated by 1994. The countries will enter into a common economic market. The worst-case scenario resulting from the agreement is one of negative growth in the region. If economic growth is limited to Paraguay's neighboring countries, migration of Paraguayans to those countries could occur. In the best-case scenario, Paraguay could benefit from expansion of exported agricultural products and livestock, which could result in progressive industrialization. However, given the lack of industrial development and education, most analysts believe that Paraguay could suffer when MERCOSUR is implemented fully. Therefore, the country will need to make the following fundamental changes in its educational policy to maintain or improve current standards of living under the trade agreement: (1) increase levels of spending on education; (2) shift to a curricular emphasison the development of productive and managerial skills; and (3) placemo.:e emphasis on science and technology.