The Cahiers Du Cinéma in 1981 Through a Programme at the Cinémathèque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Eric Rohmer's Film Theory (1948-1953)

MARCO GROSOLI FILM THEORY FILM THEORY ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY (1948-1953) IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY FROM ‘ÉCOLE SCHERER’ TO ‘POLITIQUE DES AUTEURS’ MARCO GROSOLI ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY ROHMER’S ERIC In the 1950s, a group of critics writing MARCO GROSOLI is currently Assistant for Cahiers du Cinéma launched one of Professor in Film Studies at Habib Univer- the most successful and influential sity (Karachi, Pakistan). He has authored trends in the history of film criticism: (along with several book chapters and auteur theory. Though these days it is journal articles) the first Italian-language usually viewed as limited and a bit old- monograph on Béla Tarr (Armonie contro fashioned, a closer inspection of the il giorno, Bébert 2014). hundreds of little-read articles by these critics reveals that the movement rest- ed upon a much more layered and in- triguing aesthetics of cinema. This book is a first step toward a serious reassess- ment of the mostly unspoken theoreti- cal and aesthetic premises underlying auteur theory, built around a recon- (1948-1953) struction of Eric Rohmer’s early but de- cisive leadership of the group, whereby he laid down the foundations for the eventual emergence of their full-fledged auteurism. ISBN 978-94-629-8580-3 AUP.nl 9 789462 985803 AUP_FtMh_GROSOLI_(rohmer'sfilmtheory)_rug16.2mm_v02.indd 1 07-03-18 13:38 Eric Rohmer’s Film Theory (1948-1953) Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

![Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online Since 05 February 2016, Connection on 12 April 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3336/le-portique-33-2014-straub-online-online-since-05-february-2016-connection-on-12-april-2021-323336.webp)

Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online Since 05 February 2016, Connection on 12 April 2021

Le Portique Revue de philosophie et de sciences humaines 33 | 2014 Straub ! Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/leportique/2735 DOI: 10.4000/leportique.2735 ISSN: 1777-5280 Publisher Association "Les Amis du Portique" Printed version Date of publication: 1 May 2014 ISSN: 1283-8594 Electronic reference Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online since 05 February 2016, connection on 12 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/leportique/2735; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/leportique.2735 This text was automatically generated on 12 April 2021. Tous droits réservés 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Avant-Propos Autour des films Propos autour des films Le jamais vu (à propos des Dialogues avec Leucò) Jean-Pierre Ferrini À propos de Où gît votre sourire enfoui ? de Pedro Costa Mickael Kummer Autour d'Antigone Au sujet d’Antigone Barbara Ulrich Antigone s'arrête à Ségeste Olivier Goetz Autour d'Antigone Jean-Marie Straub À propos de la mort d'Empédocle Jean-Luc Nancy and Jean-Marie Straub Après la projection du film Anna Magdalena Bach Jacques Drillon and François Narboni Retour sur Chronique d’Anna Magdalena Bach par Jean-Marie Straub Jean-Marie Straub Rencontres avec Jean-Marie Straub après les projections Après Lothringen Jean-Marie Straub Après Sicilia Jean-Marie Straub Autour de O Somma Luce et de Corneille Jean-Marie Straub Après O Somma Luce et Corneille Jean-Marie Straub Le Portique, 33 | 2014 2 Après Chronique d’Anna Magdalena Bach Jean-Marie Straub Autour de trois films Jean-Marie Straub Après Othon Jean-Marie -

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 77-82 Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague Marcos Uzal ABSTRACT This essay begins at the start of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma and with the film-making debut of five of its main members: François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. At the start they have shared approaches, tastes, passions and dislikes (above all, about a group of related film-makers from so-called ‘classical cinema’). Over the course of time, their aesthetic and political positions begin to divide them, both as people and in terms of their work, until they reach a point where reconciliation is not posible between the ‘midfield’ film-makers (Truffaut and Chabrol) and the others, who choose to control their conditions or methods of production: Rohmer, Rivette and Godard. The essay also proposes a new view of work by Rivette and Godard, exploring a relationship between their interest in film shoots and montage processes, and their affinities with various avant-gardes: early Russian avant-garde in Godard’s case and in Rivette’s, 1970s American avant-gardes and their European translation. KEYWORDS Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, radical, politics, aesthetics, montage. 77 PARADOXES OF THE NOUVELLE VAGUE In this essay the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ refers that had emerged from it: they considered that specifically to the five film-makers in this group cinematic form should be explored as a kind who emerged from the magazine Cahiers du of contraband, using the classic art of mise-en- cinéma: Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc scène rather than a revolutionary or modernist Godard, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis. -

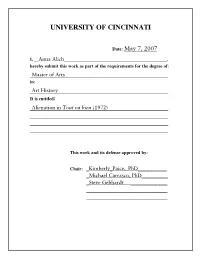

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Review of Elevator to the Gallows

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2006 Review of Elevator to the Gallows Michael Adams City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/135 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Elevator to the Gallows (Criterion Collection, 4.25.2006) Louis Malle’s 1958 film is notable for introducing many of the elements that would soon become familiar in the work of the French New Wave directors. Elevator to the Gallows conveys the sense of an artist trying to present a reality not previously seen in film, but a reality constantly touched by artifice. The film is also notable for introducing Jeanne Moreau to the international film audience. Although she had been in movies for ten years, she had not yet shown the distinctive Moreau persona. Florence Carala (Moreau) and Julien Tavernier (Maurice Ronet) are lovers plotting to kill her husband, also his boss, the slimy arms dealer Simon (Jean Wall). The narrative’s uniqueness comes from the lovers never appearing together. The film opens with a phone conversation between them, and there are incriminating photos of the once-happy couple at the end. In between, Julien pulls off what he thinks is a perfect crime. When he forgets a vital piece of evidence, however, he becomes stuck in an elevator. Then his car is stolen for a joyride by Louis (Georges Poujouly), attempting some James Dean-like rebellious swagger, and his girlfriend, Veronique (Yori Bertin). -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

CIN-1103 : Nouvelle Vague Et Nouveaux Cinémas Contenu Et

Département de littérature, théâtre et cinéma Professeur : Jean-Pierre Sirois-Trahan Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines Session : Hiver 2020 CIN-1103 : Nouvelle Vague et nouveaux cinémas Local du cours : CSL-1630 Horaire : Mercredi, 15h30-18h20 Projection : Mercredi, 18h30-21h20 (CSL-1630) Téléphone : 418-656-2131, p. 407074 Bureau : CSL-3447 Courriel : [email protected] Site personnel : https://ulaval.academia.edu/JeanPierreSiroisTrahan Contenu et objectifs du cours Dans l’histoire du cinéma mondial, la Nouvelle Vague (française) peut être considérée comme l’un des événements majeurs, de telle façon que l’on a pu dire qu’il y avait un avant et un après. Deuxième moment de la modernité au cinéma après le néoréalisme italien, son avènement au tournant des années soixante a profondément changé la donne esthétique de l’art cinématographique, et ce jusqu’à aujourd’hui. L’une des caractéristiques les plus essentielles de ce mouvement fut de considérer le cinéma, dans l’exercice même de sa praxis, de façon critique, cinéphile et réflexive. Groupée autour de la revue des Cahiers du Cinéma, cofondée par André Bazin, la Nouvelle Vague est souvent réduite à un groupe de critiques passés à la réalisation : Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer, Pierre Kast, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze et Marilù Parolini (scénariste). Aussi, il ne faudrait pas oublier ceux que l’on nomma le « groupe Rive gauche » : Agnès Varda, Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Jacques Demy, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Henri Colpi et Jacques Rozier. On peut aussi y rattacher un certain nombre d’outsiders importants, soit immédiatement précurseurs (Jean- Pierre Melville, Georges Franju, Jean Rouch et Alexandre Astruc), soit continuateurs à l’esthétique plus ou moins proche (Marguerite Duras, Jean-Marie Straub et Danièle Huillet, Paula Delsol, Maurice Pialat, Jean Eustache, Chantal Akerman, Philippe Garrel, Jacques Doillon, Catherine Breillat, Danièle Dubroux et André Téchiné). -

March 2015 Questions

March 2015 Questions General Knowledge 1 Which Swiss-born actor was the first person to be presented with an Oscar when he won the award for Best Actor, at the 1929 ceremony? 2 Which adaptation of a Jane Austen novel, directed by Ang Lee, won the Best Film BAFTA in 1996? 3 Name the biopic, due to be released in October of this year, which will be directed by Danny Boyle, written by Aaron Sorkin and star Michael Fassbender as the title character. 4 Which actor links the films Separate Tables, The Pink Panther and A Matter of Life & Death? 5 Greg Dyke is the current chair of the BFI; but which award-winning film director did Dyke succeed in the role in 2008? The 2015 Academy Awards 1 Name the Mexican director of Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), which won both the Best Film and Best Director awards at this year’s Academy Awards. 2 Which Polish film, directed by Paweł Pawlikowski, was the winner of the Best Foreign Language Film award, ahead of entries from Russia, Estonia and Argentina? 3 John Travolta presented the award for Best Original Song at this year’s ceremony alongside which singer, whose name he had mangled at last year’s awards? 4 Each year the Academy presents the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award to a specific individual; who was the recipient of the 2015 award? 5 Which film, directed by Don Hall and Chris Williams, won this year’s award for Best Animated Feature? BFI Flare: London LGBT Film Festival 2015 1 Who takes the title role in I Am Michael, a film about Michael Glatze, a pioneering gay rights activist who later denounced his homosexuality and which will open this year’s London LGBT Film Festival? 2 Name the new U.S.