Review of Elevator to the Gallows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 77-82 Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague Marcos Uzal ABSTRACT This essay begins at the start of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma and with the film-making debut of five of its main members: François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. At the start they have shared approaches, tastes, passions and dislikes (above all, about a group of related film-makers from so-called ‘classical cinema’). Over the course of time, their aesthetic and political positions begin to divide them, both as people and in terms of their work, until they reach a point where reconciliation is not posible between the ‘midfield’ film-makers (Truffaut and Chabrol) and the others, who choose to control their conditions or methods of production: Rohmer, Rivette and Godard. The essay also proposes a new view of work by Rivette and Godard, exploring a relationship between their interest in film shoots and montage processes, and their affinities with various avant-gardes: early Russian avant-garde in Godard’s case and in Rivette’s, 1970s American avant-gardes and their European translation. KEYWORDS Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, radical, politics, aesthetics, montage. 77 PARADOXES OF THE NOUVELLE VAGUE In this essay the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ refers that had emerged from it: they considered that specifically to the five film-makers in this group cinematic form should be explored as a kind who emerged from the magazine Cahiers du of contraband, using the classic art of mise-en- cinéma: Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc scène rather than a revolutionary or modernist Godard, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Series 28: 10) ND Louis Malle, VANYA on 42 STREET 1994, 119 Minutes)

April 8, 2014 (Series 28: 10) ND Louis Malle, VANYA ON 42 STREET 1994, 119 minutes) Directed by Louis Malle Written by Anton Chekhov (play “Dyadya Vanya”), David Mamet (adaptation) and Andre Gregory (screenplay) Cinematography by Declan Quinn Phoebe Brand ... Nanny Lynn Cohen ... Maman George Gaynes ... Serybryakov Jerry Mayer ... Waffles Julianne Moore ... Yelena Larry Pine ... Dr. Astrov Brooke Smith ... Sonya Wallace Shawn ... Vanya Andre Gregory ... Himself LOUIS MALLE (director) (b. October 30, 1932 in Thumeries, Nord, France—d. November 23, 1995 (age 63) in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, California) directed 33 films and television shows, including 1994 Vanya on 42nd Street, 1992 Damage, 1990 May and 1954 Station 307 (Short)—and was the cinematographer for Fools, 1987 Au Revoir Les Enfants, 1986 “God's Country” (TV 5: 1986 “God's Country” (TV Movie documentary), 1986 “And Movie documentary), 1986 “And the Pursuit of Happiness” (TV the Pursuit of Happiness” (TV Movie documentary), 1962 Vive Movie documentary), 1985 Alamo Bay, 1984 Crackers, 1981 My le tour (Documentary short), 1956 The Silent World Dinner with Andre, 1980 Atlantic City, 1978 Pretty Baby, 1975 (Documentary), and 1954 Station 307 (Short). Black Moon, 1974 A Human Condition (Documentary), 1974 Lacombe, Lucien, 1971 Murmur of the Heart, 1969 Calcutta ANTON CHEKHOV (writer—play “Dyadya Vanya”) (b. Anton (Documentary), 1967 The Thief of Paris, 1965 Viva Maria!, 1963 Pavlovich Chekhov, January 29, 1860 in Taganrog, Russian The Fire Within, 1962 A Very Private Affair, 1960 Zazie dans le Empire [now Rostov Oblast, Russia]—d. July 15, 1904 (age 44) metro, 1958 The Lovers, 1958 Elevator to the Gallows, and 1953 in Badenweiler, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) Crazeologie (Short). -

Brakhage Program 2012

The Brakhage Center Symposium 2012 Quickly becoming a tradition in the world of avant-garde filmmaking and artistry, the Brakhage Center Symposium will again be hosted this year by the University of Colorado at Boulder. In a weekend dedicated to the exploration of new ideas in cinema art, guest programmer Kathy Geritz explores Experimental Narrative. Presenters will include Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Amie Siegel, J.J. Murphy, Chris Sullivan, and Stacey Steers with musical guests The Boulder Laptop Orchestra (BLOrk). Program of Events Friday, March 16 (Muenzinger Auditorium on the CU Campus) 7:00- Multiple and Repeated Narratives 10:00 Screening: Syndromes and A Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006) Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Person. Saturday, March 17 (Visual Arts Complex 1B20 on the CU Campus) 10:00- Narratives Remade, Reused, and Revisited 12:00 Amie Siegel and Stacey Steers in Person. 1:30- Andy Warhol and Narrative 4:00 Filmmaker and critic J.J. Murphy will lecture on Warhol and narrative. 5:00- Lumière Revisited: Documentary and Narrative Hybrids 7:30 Amie Siegel, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and J. J. Murphy in Person. Sunday, March 18 (Visual Arts Complex 1B20 on the CU Campus) 10:30- Animation and Personal Journeys 1:30 Stacey Steers and Chris Sullivan in Person. 3:00- Méliès Revisited: Dreams and Fantasies 4:30 J.J. Murphy, Chris Sullivan, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Person. Special guest performance by BLOrk. (Boulder Laptop Orchestra) Topic: Experimental Narrative "We know what a narrative film is, and what an experimental film is, but what is an experimental narrative? Programmer Profile The selection of films and videos presented in this year’s Kathy Geritz symposium will present various ways filmmakers are Kathy Geritz is a film curator at Pacific Film Archive, exploring this terrain. -

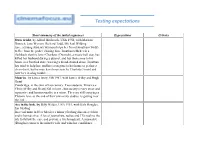

Testing Expectations

Testing expectations Short summary of the initial sequences Expectations Criteria Stage fright, by Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1950, with Marlene Dietrich, Jane Wyman, Richard Todd, Michael Wilding Jane, a young student (Wyman) helps her friend Jonathan (Todd) to flee from the police chasing him. Jonathan tells her in a flashback that his lover Charlotte (Dietrich), a music-hall star, has killed her husband during a quarrel, and has then come to his house in a frenzied state, wearing a blood-stained dress. Jonathan has tried to help her, and has even gone to her home to get her a clean dress, but he may have been seen by Charlotte's maid and now he's in a big trouble ... Maurice, by James Ivory, GB 1987, with James Wilby and Hugh Grant Cambridge, at the start of last century. Two students, Maurice e Clive (Wilby and Grant) fall in love - but society is very strict and repressive and homosexuality is a crime. They are still enjoying a Platonic love as the end of their university studies is getting near the end ... Ace in the hole, by Billy Wilder, USA 1951, with Kirk Douglas, Jan Sterling In a coal mine in New Mexico a miner (Sterling) has an accident and is buried alive. A lot of journalists, radios and TVs rush to the site to follow the case and provide a live broadcast. A journalist (Douglas) contacts the miner's wife and wins her confidence ... Arlington Road, by Mark Pellington, USA 1999, with Jeff Bridges, Tim Robbins, Joan Cusack Michael Faraday (Bridges), a widower, lives with his 10-year-old son in a house in the suburbs of Washington. -

The Calhoun School

THE CALHOUN SCHOOL TABLE OF CONTENTS Important Information 3 ❏ Course Registration Process ❏ Independent Study ❏ Adding or Dropping Classes ❏ External Academic Work ❏ Accelerating Mathematics Coursework Academic Planning Advice 6 ❏ For All Upper Schoolers ❏ For Rising Ninth Graders ❏ For Rising Tenth Graders ❏ For Rising Eleventh Graders ❏ For Rising Twelfth Graders 2019-2020 US Course Offerings & Descriptions ❏ New Courses for 2019-2020 9 ❏ English 10 ❏ Social Studies 18 ❏ Mathematics 26 ❏ World Languages 32 ❏ Science 39 ❏ Computer & Information Science 45 ❏ Music 46 ❏ Theater Arts 51 ❏ Visual Arts 55 ❏ Community Service 62 ❏ Physical Education 63 ❏ Special Courses 64 Other Academic Policies 66 ❏ Language Waiver Criteria ❏ Incompletes ❏ Academic/Social Probation COVER ILLUSTRATION: Oliver Rauch, Calhoun Class of 2019 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION COURSE REGISTRATION PROCESS Each year during Mod 5, there will be a ten-day registration period during which students in grades 9-11 will select courses for the following school year. The registration process will begin at a special Town Meeting, which will be devoted to the introduction of the online Course Catalogue (including a preview of new courses) and an overview of the course registration process. Following the Town Meeting, cluster advisers will share a Course Registration Packet with each of their advisees. The packet will include the student’s current academic transcript, a Transcript Audit Review Form, and a Course Selection Form. Although it is ultimately the student’s responsibility to complete his/her Course Selection Form, this process works best when students consult with teachers, cluster advisors, and parents/guardians to make informed decisions. It is advised that each student utilize the Transcript Review Audit Form to ensure that adequate progress is being made toward all Calhoun graduation requirements. -

Of Gods and Men

A Sony Pictures Classics Release Armada Films and Why Not Productions present OF GODS AND MEN A film by Xavier Beauvois Starring Lambert Wilson and Michael Lonsdale France's official selection for the 83rd Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film 2010 Official Selections: Toronto International Film Festival | Telluride Film Festival | New York Film Festival Nominee: 2010 European Film Award for Best Film Nominee: 2010 Carlo di Palma European Cinematographer, European Film Award Winner: Grand Prix; Ecumenical Jury Prize - 2010Cannes Film Festival Winner: Best Foreign Language Film, 2010 National Board of Review Winner: FIPRESCI Award for Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, 2011 Palm Springs International Film Festival www.ofgodsandmenmovie.com Release Date (NY/LA): 02/25/2011 | TRT: 120 min MPAA: Rated PG-13 | Language: French East Coast Publicist West Coast Publicist Distributor Sophie Gluck & Associates Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Sophie Gluck Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 124 West 79th St. Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10024 110 S. Fairfax Ave., Ste 310 550 Madison Avenue Phone (212) 595-2432 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] Phone (323) 634-7001 Phone (212) 833-8833 Fax (323) 634-7030 Fax (212) 833-8844 SYNOPSIS Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay… come what may. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt.