H-France Review Volume 18 (2018) Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

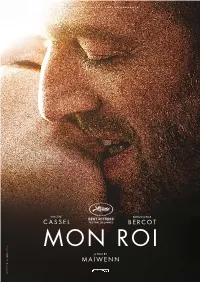

MY KING (MON ROI) a Film by Maïwenn

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRESOR PRESENTS MY KING (MON ROI) A film by Maïwenn “Bercot is heartbreaking, and Cassel has never been better… it’s clear that Maïwenn has something to say — and a clear, strong style with which to express it.” – Peter Debruge, Variety France / 2015 / Drama, Romance / French 125 min / 2.40:1 / Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound Opens in New York on August 12 at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Opens in Los Angeles on August 26 at Laemmle Royal New York Press Contacts: Ryan Werner | Cinetic | (212) 204-7951 | [email protected] Emilie Spiegel | Cinetic | (646) 230-6847 | [email protected] Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman | Shotwell Media | (310) 450-5571 | [email protected] Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | PR & Promotion | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tony (Emmanuelle Bercot) is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on the turbulent ten-year relationship she experienced with Georgio (Vincent Cassel). Why did they love each other? Who is this man whom she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free. LOGLINE Acclaimed auteur Maïwenn’s magnum opus about the real and metaphysical pain endured by a woman (Emmanuelle Bercot) who struggles to leave a destructive co-dependent relationship with a charming, yet extremely self-centered lothario (Vincent Cassel). -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

CIN-1103 : Nouvelle Vague Et Nouveaux Cinémas Contenu Et

Département de littérature, théâtre et cinéma Professeur : Jean-Pierre Sirois-Trahan Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines Session : Hiver 2020 CIN-1103 : Nouvelle Vague et nouveaux cinémas Local du cours : CSL-1630 Horaire : Mercredi, 15h30-18h20 Projection : Mercredi, 18h30-21h20 (CSL-1630) Téléphone : 418-656-2131, p. 407074 Bureau : CSL-3447 Courriel : [email protected] Site personnel : https://ulaval.academia.edu/JeanPierreSiroisTrahan Contenu et objectifs du cours Dans l’histoire du cinéma mondial, la Nouvelle Vague (française) peut être considérée comme l’un des événements majeurs, de telle façon que l’on a pu dire qu’il y avait un avant et un après. Deuxième moment de la modernité au cinéma après le néoréalisme italien, son avènement au tournant des années soixante a profondément changé la donne esthétique de l’art cinématographique, et ce jusqu’à aujourd’hui. L’une des caractéristiques les plus essentielles de ce mouvement fut de considérer le cinéma, dans l’exercice même de sa praxis, de façon critique, cinéphile et réflexive. Groupée autour de la revue des Cahiers du Cinéma, cofondée par André Bazin, la Nouvelle Vague est souvent réduite à un groupe de critiques passés à la réalisation : Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer, Pierre Kast, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze et Marilù Parolini (scénariste). Aussi, il ne faudrait pas oublier ceux que l’on nomma le « groupe Rive gauche » : Agnès Varda, Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Jacques Demy, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Henri Colpi et Jacques Rozier. On peut aussi y rattacher un certain nombre d’outsiders importants, soit immédiatement précurseurs (Jean- Pierre Melville, Georges Franju, Jean Rouch et Alexandre Astruc), soit continuateurs à l’esthétique plus ou moins proche (Marguerite Duras, Jean-Marie Straub et Danièle Huillet, Paula Delsol, Maurice Pialat, Jean Eustache, Chantal Akerman, Philippe Garrel, Jacques Doillon, Catherine Breillat, Danièle Dubroux et André Téchiné). -

Of Christophe Honoré: New Wave Legacies and New Directions in French Auteur Cinema

SEC 7 (2) pp. 135–148 © Intellect Ltd 2010 Studies in European Cinema Volume 7 Number 2 © Intellect Ltd 2010. Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/seci.7.2.135_1 ISABELLE VANDERSCHELDEN Manchester Metropolitan University The ‘beautiful people’ of Christophe Honoré: New Wave legacies and new directions in French auteur cinema ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Drawing on current debates on the legacy of the New Wave on its 50th anniversary French cinema and the impact that it still retains on artistic creation and auteur cinema in France auteur cinema today, this article discusses three recent films of the independent director Christophe French New Wave Honoré: Dans Paris (2006), Les Chansons d’amour/Love Songs (2007) and La legacies Belle personne (2008). These films are identified as a ‘Parisian trilogy’ that overtly Christophe Honoré makes reference and pays tribute to New Wave films’ motifs and iconography, while musical offering a modern take on the representation of today’s youth in its modernity. Study- adaptation ing Honoré’s auteurist approach to film-making reveals that the legacy of the French Paris New Wave can elicit and inspire the personal style and themes of the auteur-director, and at the same time, it highlights the anchoring of his films in the Paris of today. Far from paying a mere tribute to the films that he loves, Honoré draws life out his cinephilic heritage and thus redefines the notion of French (European?) auteur cinema for the twenty-first century. 135 December 7, 2010 12:33 Intellect/SEC Page-135 SEC-7-2-Finals Isabelle Vanderschelden 1Alltranslationsfrom Christophe Honoré is an independent film-maker who emerged after 2000 and French sources are mine unless otherwise who has overtly acknowledged the heritage of the New Wave as formative in indicated. -

Le Cinéma Trouve Son Bonheur En Pays De La Loire

Ouest France - Pays de la Loire 18/02/2017 N° 22082 page 6 Le cinéma trouve son bonheur en Pays de la Loire La région offre un large choix de paysages qui séduit les réalisateurs de films. Ce n’est pas nouveau pour les longs-métrages. Mais, pour la première fois en 2016, deux séries TV ont été tournées ici. Faciliter le travail du réalisateur petits châteaux, encore meublés, Sang de la vigne, à Gorges et Saint- Comme d'autres régions, les Pays de reste attractive. C’est beaucoup Fiacre (Loire-Atlantique), déjà diffusé la Loire disposent d'un bureau d'ac plus accessible que les grands châ sur France 3, et Mon frère bien aimé, téléfilm avec Olivier Marchai et Mi cueil des tournages. Son rôle : faire teaux de la région Centre », men gagner du temps aux réalisateurs en tionne la responsable du bureau des chael Young, programmé le 1er mars sur France 2. leur proposant des sites et un réseau tournages. Mais depuis quelques de professionnels confirmés dans le années, les comédies familiales, ro En tournage cette année De nombreux projets de tournage domaine de l'image, du son, du cos mantiques ou dramatiques se dé sont engagés en 2017. D'abord tume, du maguillage, de la coiffure... roulent dans des décors contempo « Certains réalisateurs viennent rains et souvent en zone urbaine. quatre longs-métrages : Emil Mate- sic de Sylvain Labrosse, à Saint-Na avec une idée précise, d’autres zaire au printemps ; Mademoiselle nous interrogent. Notre mission est Bientôt sur les écrans de Joncquières d'Emmanuel Mouret, de faciliter leur tâche et que tout se Tournés dans la région en 2015 dans un château d'Anjou au second passe bien », explique Pauline Le et 2016, quatre longs-métrages semestre ; Si demain de Fabienne Floch, responsable du bureau des seront bientôt diffusés sur grand tournages. -

François Truffaut's Jules and Jim and the French New Wave, Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 29, núms. 1-2 (2019) · ISSN: 2014-668X François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim and the French New Wave, Re-viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract Truffaut’s early protagonists, like many of those produced by the New Wave, were rebels or misfits who felt stifled by conventional social definitions. His early cinematic style was as anxious to rip chords as his characters were. Unlike Godard, Truffaut went on in his career to commit himself, not to continued experiment in film form or radical critique of visual imagery, but to formal themes like art and life, film and fiction, and art and education. This article reconsiders a film that embodies such themes, in addition to featuring characters who feel stifled by conventional social definitions: Jules and Jim. Keywords: François Truffaut; French film; New Wave; Jules and Jim; Henri- Pierre Roché Resumen Los primeros protagonistas de Truffaut, como muchos de los producidos por la New Wave, eran rebeldes o inadaptados que se sentían agobiados por las convenciones sociales convencionales. Su estilo cinematográfico temprano estaba tan ansioso por romper moldes como sus personajes. A diferencia de Godard, Truffaut continuó en su carrera comprometiéndose, no a seguir experimentando en forma de película o crítica radical de las imágenes visuales, sino a temas formales como el arte y la vida, el cine y la ficción, y el arte y la educación. Este artículo reconsidera una película que encarna dichos temas, además de presentar personajes que se sienten ahogados: Jules y Jim. Palabras clave: François Truffaut, cine francés, New Wave; Jules and Jim, Henri-Pierre Roché. -

General Education Course Proposal University of Mary Washington

GENERAL EDUCATION COURSE PROPOSAL UNIVERSITY OF MARY WASHINGTON Use this form to submit EXISTING courses for review. If this course will be submitted for review in more than one category, submit a separate proposal for each category. COURSE NUMBER: FSEM 100F COURSE TITLE: THE FRENCH NEW WAVE: CINEMA AND SOCIETY SUBMITTED BY: Leonard R. Koos DATE: 1/28/08 This course proposal is submitted with the department’s approval. (Put a check in the box X to the right.) If part of a science sequence involving two departments, both departments approve. THIS COURSE IS PROPOSED FOR (check one). First-Year Seminar X Quantitative Reasoning Global Inquiry Human Experience and Society Experiential Learning Arts, Literature, and Performance: Process or Appreciation Natural Science (include both parts of the sequence) NOTE: See the report entitled “General Education Curriculum as Approved by the Faculty Senate,” dated November 7, 2007, for details about the general education categories and the criteria that will be used to evaluate courses proposed. The report is available at www.jtmorello.org/gened. RATIONALE: Using only the space provided in the box below, briefly state why this course should be approved as a general education course in the category specified above. Attach a course syllabus. Submit this form and attached syllabus electronically as one document to John Morello ([email protected]). All submissions must be in electronic form. My first-year seminar (The French New Wave: Cinema and Society), which has already been taught twice, uses the films of the French Wave as its primary “texts.” Secondary readings as well as Blackboard postings help prepare and organize our class discussions of individual films and directors. -

Let My People Go! a Film by Mikael Buch

Let My People Go! a film by Mikael Buch Theatrical & Festival Booking Contact: Clemence Taillandier, Zeitgeist Films (201) 736-0261 • [email protected] Marketing Contact: Ben Crossley-Marra, Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 x10 • [email protected] Publicity Contact (New York and Los Angeles): Sasha Berman, Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 • [email protected] A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE Let My People Go! a film by Mikael Buch A sweet and hilarious fusion of gay romantic comedy, Jewish family drama and French bedroom farce, Mikael Buch’s Let My People Go! follows the travails and daydreams of the lovelorn Reuben (Regular Lovers’ Nicolas Maury), a French-Jewish gay mailman living in fairytale Finland (where he got his MA in “Comparative Sauna Cultures”) with his gorgeous Nordic boyfriend. But just before Passover, a series of mishaps and a lovers’ quarrel exile the heartbroken Reuben back to Paris and his zany family— including Almodovar goddess Carmen Maura (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, Volver) as his ditzy mom, and Truffaut regular Jean-François Stévenin as his lothario father. Scripted by director Mikael Buch and renowned arthouse auteur Christophe Honoré (Love Songs), Let My People Go! both celebrates and upends Jewish and gay stereotypes with wit, gusto and style to spare. The result is deeply heartwarming, fabulously kitschy and hysterically funny. AN INTERVIEW WITH MIKAEL BUCH What was your background prior to making your first feature film? My father is from Argentina and my mother is Moroccan—a complicated mixture in the first place. I was born in France, but we moved to Taiwan when I was two months old. -

Mon Roi a Film by Maïwenn Photo : ©Productions Du Trésor / Shanna Besson Studiocanal and Les Productions Du Trésor Present

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRÉ SOR PRESENTS VINCENT EMMANUELLE CASSEL BERCOT MON ROI A FILM BY MAÏWENN PHOTO : ©PRODUCTIONS DU TRÉSOR / SHANNA BESSON STUDIOCANAL AND LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRÉSOR PRESENT VINCENT EMMANUELLE CASSEL BERCOT MON ROI RUNNING TIME: 2H08 SYNOPSIS Tony is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on a turbulent relationship that she experienced with Georgio. Why did they love each other? Who is this man that she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free… INTERVIEW WITH MAÏWENN MON ROI deals with a passionate and destructive Was it clear from the start that you wouldn’t be relationship that unfolds over a decade. It’s a story appearing in the film? about relationships viewed from the outside, and Yes. I wanted to work with Emmanuelle Bercot, and I also wanted as such is very different to the kinds of films you to make a film that I wasn’t in, to see what that could bring to have previously made. me as a director. It’s a subject I’ve been thinking about for years, without ever making the film. It scared me; I didn’t feel I was sufficiently The character of Georgio is very complex and also mature to deal with it. I’d written numerous versions without very mysterious… being satisfied with any of them. -

Contact in San Sebastian

CONTACT IN SAN SEBASTIAN Naomi DENamUR +33 6 86 83 03 85 [email protected] SAN PaRiS oFFiCE 5, rue Darcet 75017 Paris, France SEBASTIAN Tel: +33 1 44 69 59 59 Fax: +33 1 44 69 59 42 www.le-pacte.com 2011 COMPLETED LAND OF VENICE INTERNATIONAL CRITICS’ WEEK 2011 OBLIVION (LA TERRE OUTRAGÉE) a film by Michale Boganim (odessa... odessa!) Cast: olga Kurylenko Producers: Les Films du Poisson, Vandertastic, apple Film Duration: 115min Genre: Drama Language: Russian, French April 26th, 1986. On that day, Anya and Piotr celebrate their marriage. Little Valery and his father Alexei, a physicist at the power station in Chernobyl, plant an apple tree. Nikolai, the forest warden, makes his rounds in the surrounding forests. Then, an accident occurs at the power station. Insidiously, the radioactivity transforms nature. The rain is yellow, the trees turn red. Piotr, a volunteer fireman, leaves to extinguish the flames. He never returns. A few days later, the population is evacuated. Alexei, forced to keep silent by the authorities, prefers to disappear. Ten years later, the deserted Pripiat has become a no man’s land and a bizarre tourist attraction. Anya comes to the Zone every month as a tour guide, while Valery goes there to look for traces of his father. And Nikolai continues to cultivate a poisonous garden. With the passing of time, will they be able to accept the hope of a new life? COMPLETED LAST WINTER (L’HIVER DERNIER) a film by John Shank Cast: Vincent Rottiers, anaïs Demoustier, VENICE Florence Loiret Caille DAYS 2011 Producers: Silex Films, Tarantula Films Duration: 98min Genre: Drama Language: French Somewhere on isolated mountainous plains. -

Frontier of Dawn

Rectangle Productions presents Louis Garrel Laura Smet FRONTIER OF DAWN La frontière de l’aube a film by Philippe Garrel France – 105 min – B&W – 1.85 - Dolby SRD INTERNATIONAL PRESS WORLD SALES Viviana Andriani FILMS DISTRIBUTION 32 rue Godot de Mauroy 75009 PARIS 34, rue du Louvre | 75001 PARIS Tel/fax: +33 1 42 66 36 35 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 99 In Cannes: In Cannes: Booth E5/F8 Cell: +33(0)6 80 16 81 39 Tel: +33 4 92 99 33 29 [email protected] www.filmsdistribution.com In Cannes SYNOPSIS Carole, a celebrity neglected by her husband, falls for François, a young photographer. Returning from a business trip the husband surprises them, and the lovers have to end their relationship. Carole gradually drifts into madness and commits suicide. One year later, a few hours before his wedding, François has a vision. It’s Carole, calling him from the other world… INTERVIEW WITH PHILIPPE GARREL How do you explain the title, Frontier of Dawn? While I was writing it, the film was called Heaven of the Angels, an expression I found in Blanche ou l’oubli by Louis Aragon. I liked it a lot but I was put off by the neo-Catholic side. And one night, at four in the morning, I came up with Frontier of Dawn, which evoked both the suicide and the ghost themes. I made the film with this title in mind and it gave me the key to each scene. Maybe the title is too deliberately poetic. I knew a director, Pierre Romans, who said an actor must never act poetic and to be poetic, you have to act in a realistic manner, with a trivial element.