Appendix: Methods of Studying Nucleic Acids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restriction Endonucleases

Molecular Biology Problem Solver: A Laboratory Guide. Edited by Alan S. Gerstein Copyright © 2001 by Wiley-Liss, Inc. ISBNs: 0-471-37972-7 (Paper); 0-471-22390-5 (Electronic) 9 Restriction Endonucleases Derek Robinson, Paul R. Walsh, and Joseph A. Bonventre Background Information . 226 Which Restriction Enzymes Are Commercially Available? . 226 Why Are Some Enzymes More Expensive Than Others? . 227 What Can You Do to Reduce the Cost of Working with Restriction Enzymes? . 228 If You Could Select among Several Restriction Enzymes for Your Application, What Criteria Should You Consider to Make the Most Appropriate Choice? . 229 What Are the General Properties of Restriction Endonucleases? . 232 What Insight Is Provided by a Restriction Enzyme’s Quality Control Data? . 233 How Stable Are Restriction Enzymes? . 236 How Stable Are Diluted Restriction Enzymes? . 236 Simple Digests . 236 How Should You Set up a Simple Restriction Digest? . 236 Is It Wise to Modify the Suggested Reaction Conditions? . 237 Complex Restriction Digestions . 239 How Can a Substrate Affect the Restriction Digest? . 239 Should You Alter the Reaction Volume and DNA Concentration? . 241 Double Digests: Simultaneous or Sequential? . 242 225 Genomic Digests . 244 When Preparing Genomic DNA for Southern Blotting, How Can You Determine If Complete Digestion Has Been Obtained? . 244 What Are Your Options If You Must Create Additional Rare or Unique Restriction Sites? . 247 Troubleshooting . 255 What Can Cause a Simple Restriction Digest to Fail? . 255 The Volume of Enzyme in the Vial Appears Very Low. Did Leakage Occur during Shipment? . 259 The Enzyme Shipment Sat on the Shipping Dock for Two Days. -

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION in Silico Signature Prediction

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION In Silico Signature Prediction Modeling in Cytolethal Distending Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Strains Maryam Javadi, Mana Oloomi*, Saeid Bouzari Department of Molecular Biology, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran 13164, Iran http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-15-69-s001.pdf Supplementary Table 6. Aalphabetic abbreviation and description of putative conserved domains Alphabetic Abbreviation Description 17 Large terminase protein 2_A_01_02 Multidrug resistance protein 2A0115 Benzoate transport; [Transport and binding proteins, Carbohydrates, organic alcohols] 52 DNA topisomerase II medium subunit; Provisional AAA_13 AAA domain; This family of domains contain a P-loop motif AAA_15 AAA ATPase domain; This family of domains contain a P-loop motif AAA_21 AAA domain AAA_23 AAA domain ABC_RecF ATP-binding cassette domain of RecF; RecF is a recombinational DNA repair ATPase ABC_SMC_barmotin ATP-binding cassette domain of barmotin, a member of the SMC protein family AcCoA-C-Actrans Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferases AHBA_syn 3-Amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid synthase family (AHBA_syn) AidA Type V secretory pathway, adhesin AidA [Cell envelope biogenesis] Ail_Lom Enterobacterial Ail/Lom protein; This family consists of several bacterial and phage Ail_Lom proteins AIP3 Actin interacting protein 3; Aip3p/Bud6p is a regulator of cell and cytoskeletal polarity Aldose_epim_Ec_YphB Aldose 1-epimerase, similar to Escherichia coli YphB AlpA Predicted transcriptional regulator [Transcription] AntA AntA/AntB antirepressor AraC AraC-type -

Open Matthew R Moreau Ph.D. Dissertation Finalfinal.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Pathobiology Program PATHOGENOMICS AND SOURCE DYNAMICS OF SALMONELLA ENTERICA SEROVAR ENTERITIDIS A Dissertation in Pathobiology by Matthew Raymond Moreau 2015 Matthew R. Moreau Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 The Dissertation of Matthew R. Moreau was reviewed and approved* by the following: Subhashinie Kariyawasam Associate Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Bhushan M. Jayarao Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Mary J. Kennett Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Vijay Kumar Assistant Professor, Department of Nutritional Sciences Anthony Schmitt Associate Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Head of the Pathobiology Graduate Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis (SE) is one of the most frequent common causes of morbidity and mortality in humans due to consumption of contaminated eggs and egg products. The association between egg contamination and foodborne outbreaks of SE suggests egg derived SE might be more adept to cause human illness than SE from other sources. Therefore, there is a need to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the ability of egg- derived SE to colonize the chicken intestinal and reproductive tracts and cause disease in the human host. To this end, the present study was carried out in three objectives. The first objective was to sequence two egg-derived SE isolates belonging to the PFGE type JEGX01.0004 to identify the genes that might be involved in SE colonization and/or pathogenesis. -

Roles of Methylation and Sequestration in the Mechanisms of DNA Replication in Some Members of the Enterobacteriaceae Family

Chapter 12 Roles of Methylation and Sequestration in the Mechanisms of DNA Replication in some Members of the Enterobacteriaceae Family Amine Aloui, Alya El May, Saloua Kouass Sahbani and Ahmed Landoulsi Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/51724 1. Introduction When growing cells divide, they need to copy their genetic material and distribute it to en‐ sure that each daughter cell receives one copy. This is a challenging task especially when the enormous length of the DNA compared to the cell size is considered. During DNA replica‐ tion, organization of the chromosomes is even more demanding, since replication forks con‐ tinuously produce new DNA. This DNA contains all the information required to build the cells and tissues of a prokaryotic or an eukaryotic organism. The exact replication of this in‐ formation in any species assures its genetic continuity from generation to generation and is critical to the normal development of an individual. The information stored in DNA is ar‐ ranged in hereditary units known as genes that control the identifiable traits of an organism. Discovery of the structure of DNA and subsequent elucidation of how DNA directs synthe‐ sis of RNA, which then directs assembly of proteins -the so-called central dogma - were monumental achievements that marked the early days of molecular biology. However, the simplified representation of the central dogma as DNA → RNA → protein does not reflect the role of proteins in the synthesis of nucleic acids. Moreover, proteins are largely responsi‐ ble for regulating DNA replication and gene expression, the entire process whereby the in‐ formation encoded in DNA is decoded into the proteins that characterize various cell types. -

Deciphering Bacterial Epigenomes Using Modern Sequencing Technologies

REVIEWS Deciphering bacterial epigenomes using modern sequencing technologies John Beaulaurier, Eric E. Schadt and Gang Fang * Abstract | Prokaryotic DNA contains three types of methylation: N6-methyladenine, N4-methylcytosine and 5-methylcytosine. The lack of tools to analyse the frequency and distribution of methylated residues in bacterial genomes has prevented a full understanding of their functions. Now , advances in DNA sequencing technology , including single- molecule, real- time sequencing and nanopore- based sequencing, have provided new opportunities for systematic detection of all three forms of methylated DNA at a genome- wide scale and offer unprecedented opportunities for achieving a more complete understanding of bacterial epigenomes. Indeed, as the number of mapped bacterial methylomes approaches 2,000, increasing evidence supports roles for methylation in regulation of gene expression, virulence and pathogen–host interactions. Phase variation DNA methylation was discovered in bacteria more than MTases has been found to play important regulatory 1 2–12 A means by which reversible a half century ago . It is now known that modification roles in bacteria . RM systems protect cells from variation of protein expression of the four canonical DNA bases by methylation can act invading DNA by methylating endogenous DNA and is achieved in bacteria, often in as an epigenetic regulator — that is, it can impart dis- cleaving non- methylated foreign DNA2,4. RM sys- an ON/OFF manner. The process creates phenotypic tinct and reversible regulatory states to identical genetic tems are divided into three main categories based diversity in a clonally expanded sequences. In eukaryotes, epigenetic regulation can on the subunits involved and the precise site of DNA population and allows the occur at multiple levels: DNA methylation, nucleosome restriction13–16 (Fig. -

The Microbiota-Produced N-Formyl Peptide Fmlf Promotes Obesity-Induced Glucose

Page 1 of 230 Diabetes Title: The microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide fMLF promotes obesity-induced glucose intolerance Joshua Wollam1, Matthew Riopel1, Yong-Jiang Xu1,2, Andrew M. F. Johnson1, Jachelle M. Ofrecio1, Wei Ying1, Dalila El Ouarrat1, Luisa S. Chan3, Andrew W. Han3, Nadir A. Mahmood3, Caitlin N. Ryan3, Yun Sok Lee1, Jeramie D. Watrous1,2, Mahendra D. Chordia4, Dongfeng Pan4, Mohit Jain1,2, Jerrold M. Olefsky1 * Affiliations: 1 Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 2 Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3 Second Genome, Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA. 4 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. * Correspondence to: 858-534-2230, [email protected] Word Count: 4749 Figures: 6 Supplemental Figures: 11 Supplemental Tables: 5 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 22, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 230 ABSTRACT The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and associated metabolites changes dramatically with diet and the development of obesity. Although many correlations have been described, specific mechanistic links between these changes and glucose homeostasis remain to be defined. Here we show that blood and intestinal levels of the microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), are elevated in high fat diet (HFD)- induced obese mice. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the N-formyl peptide receptor Fpr1 leads to increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance, dependent upon glucagon- like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Obese Fpr1-knockout (Fpr1-KO) mice also display an altered microbiome, exemplifying the dynamic relationship between host metabolism and microbiota. -

Q 297 Suppl USE

The following supplement accompanies the article Atlantic salmon raised with diets low in long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids in freshwater have a Mycoplasma dominated gut microbiota at sea Yang Jin, Inga Leena Angell, Simen Rød Sandve, Lars Gustav Snipen, Yngvar Olsen, Knut Rudi* *Corresponding author: [email protected] Aquaculture Environment Interactions 11: 31–39 (2019) Table S1. Composition of high- and low LC-PUFA diets. Stage Fresh water Sea water Feed type High LC-PUFA Low LC-PUFA Fish oil Initial fish weight (g) 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 80 200 Feed size (mm) 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 3.5 4.9 North Atlantic fishmeal (%) 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 35 25 Plant meals (%) 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 39 46 Additives (%) 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 2.6 3.3 North Atlantic fish oil (%) 9.9 12 12 15 16 17 18 0 0 0 0 0 1.2 1.2 23 26 Linseed oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.8 8.1 8.1 9.7 11 10 11 0 0 Palm oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.2 3.8 3.8 5.4 5.9 5.8 5.9 0 0 Protein (%) 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 44 41 Fat (%) 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 28 31 EPA+DHA (% diet) 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.1 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 4 4.2 Table S2. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11179-9 OPEN Genome-wide systematic identification of methyltransferase recognition and modification patterns Torbjørn Ølshøj Jensen1, Christian Tellgren-Roth2, Stephanie Redl1,3, Jérôme Maury1, Simo Abdessamad Baallal Jacobsen1, Lasse Ebdrup Pedersen 1 & Alex Toftgaard Nielsen 1 1234567890():,; Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation patterns using single molecule real-time DNA sequencing has boosted the number of publicly available methylomes. However, there is a lack of tools coupling methylation patterns and the corresponding methyltransferase genes. Here we demonstrate a high-throughput method for coupling methyltransferases with their respective motifs, using automated cloning and analysing the methyltransferases in vectors carrying a strain-specific cassette containing all potential target sites. To validate the method, we analyse the genomes of the thermophile Moorella thermoacetica and the mesophile Acetobacterium woodii, two acetogenic bacteria having substantially modified genomes with 12 methylation motifs and a total of 23 methyltransferase genes. Using our method, we characterize the 23 methyltransferases, assign motifs to the respective enzymes and verify activity for 11 of the 12 motifs. 1 The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability (CfB), Technical University of Denmark (DTU), DK-2800 Lyngby, Denmark. 2 Uppsala Genome Center, National Genomics Infrastructure, SciLifeLab, SE-751 08 Uppsala, Sweden. 3 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. Correspondence -

Methylation of Adenine in the Nuclear DNA of "Tetrahymena" Is Internucleosomal and Independent of Histone H1 Kathleen M

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Biological Sciences Faculty Research and Biological Sciences, Department of Publications 1-1-2002 Methylation of Adenine in the Nuclear DNA of "Tetrahymena" is Internucleosomal and Independent of Histone H1 Kathleen M. Karrer Marquette University, [email protected] Teresa Ann Van Nuland Marquette University Published version. Nucleic Acids Research, Vol. 30, No. 6 (2002): 1354-1370. DOI. © 2002 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. 1364-1370 Nucleic Acids Research, 2002, Vol. 30, No. 6 © 2002 Oxford University Press Methylation of adenine in the nuclear DNA of Tetrahymena is internucleosomal and independent of histone H1 Kathleen M. Karrer* and Teresa A. VanNuland Department of Biology, Wehr Life Sciences, Marquette University, PO Box 1881, Milwaukee, WI 53201·1881, USA Received November 19. 2001; Revised and Accepted January 28. 2002 DDBJ/EMBUGenBank accession nos+ ABSTRACT In the somatic macronucleus of Tetrahymena -0.8% of the There are about 50 copies of each chromosome in the adenine residues are methylated. Because the genome is -75% A-T, this amounts to approximately one methylated adenine somatic macronucleus of the ciliated protozoan per 165 bp of DNA. In vivo, methylation occurs at the Tetrahymena. Approximately 0.8% of the adenine resi sequence 5'-NAT-3' (9). A small fraction of the methylated dues in the macronuclear DNA of Tetrahymena are adenines occur in the sequence GA TC, and can be assayed by methylated to N~methyladenine. The degree of methy digestion with restriction enzyme isoschizomers that are differ lation varies between sites from a very low percentage entially sensitive to adenine methylation. -

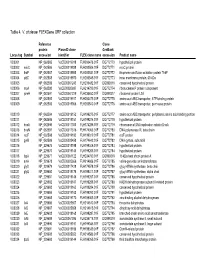

Table 4. V. Cholerae Flexgene ORF Collection

Table 4. V. cholerae FLEXGene ORF collection Reference Clone protein PlasmID clone GenBank Locus tag Symbol accession identifier FLEX clone name accession Product name VC0001 NP_062585 VcCD00019918 FLH200476.01F DQ772770 hypothetical protein VC0002 mioC NP_062586 VcCD00019938 FLH200506.01F DQ772771 mioC protein VC0003 thdF NP_062587 VcCD00019958 FLH200531.01F DQ772772 thiophene and furan oxidation protein ThdF VC0004 yidC NP_062588 VcCD00019970 FLH200545.01F DQ772773 inner membrane protein, 60 kDa VC0005 NP_062589 VcCD00061243 FLH236482.01F DQ899316 conserved hypothetical protein VC0006 rnpA NP_062590 VcCD00025697 FLH214799.01F DQ772774 ribonuclease P protein component VC0007 rpmH NP_062591 VcCD00061229 FLH236450.01F DQ899317 ribosomal protein L34 VC0008 NP_062592 VcCD00019917 FLH200475.01F DQ772775 amino acid ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein VC0009 NP_062593 VcCD00019966 FLH200540.01F DQ772776 amino acid ABC transproter, permease protein VC0010 NP_062594 VcCD00019152 FLH199275.01F DQ772777 amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding portion VC0011 NP_062595 VcCD00019151 FLH199274.01F DQ772778 hypothetical protein VC0012 dnaA NP_062596 VcCD00017363 FLH174286.01F DQ772779 chromosomal DNA replication initiator DnaA VC0013 dnaN NP_062597 VcCD00017316 FLH174063.01F DQ772780 DNA polymerase III, beta chain VC0014 recF NP_062598 VcCD00019182 FLH199319.01F DQ772781 recF protein VC0015 gyrB NP_062599 VcCD00025458 FLH174642.01F DQ772782 DNA gyrase, subunit B VC0016 NP_229675 VcCD00019198 FLH199346.01F DQ772783 hypothetical protein -

Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism in Human Epidermis* Jean De Bersaques, Md

THE JOURNAL OP INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY Vol. 4s, No. Z Copyright 1957 by The Williams & Wilkins Co. Fri nte,1 in U.S.A. PURINE AND PYRIMIDINE METABOLISM IN HUMAN EPIDERMIS* JEAN DE BERSAQUES, MD. The continuous cellular renewal occurring inthine, which contained 5% impurity, and for uric the epidermis requires a very active synthesisacid, which consisted of 3 main components. The reaction was stopped after 1—2 hours in- and breakdown of nuclear and cytoplasmiecubation at 37° and the products were spotted on nucleic acids. Data on the enzyme systemsWhatman 1 filter paper sheets. According to the participating in these metabolic processes arereaction products expected, a choice was made of rather fragmentary (1—9) and some are, inat least 2 among the following solvents, all used terms of biochemical time, in need of up- in ascending direction: 1. isoamyl alcohol—5% Na2HPO4 (1:1), dating. In some other publications (10—18), 2. water-saturated n-butanol, the presence and concentration of various in- 3. distilled water, termediate products is given. 4. 80% formic acid—n-hutanol——n-propanol— In this paper, we tried to collect and supple- acetone—30% trichloro-aeetic acid (5:8:4: ment these data by investigating the presence 5:3), 5. n-butanol——4% boric acid (43:7), or absence in epidermis of enzyme systems 6. isobutyrie acid—water—ammonia 0.880—ver- that have been described in other tissues. sene 0.1M(500:279:21:8), This first investigation was a qualitative one, 7. upper phase of ethyl acetate—water—formic and some limitations were set by practical acid (12:7:1), 8. -

Deep Sequencing of the Camellia Sinensis Transcriptome Revealed

Shi et al. BMC Genomics 2011, 12:131 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/131 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Deep sequencing of the Camellia sinensis transcriptome revealed candidate genes for major metabolic pathways of tea-specific compounds Cheng-Ying Shi1†, Hua Yang1†, Chao-Ling Wei1†, Oliver Yu1,2, Zheng-Zhu Zhang1, Chang-Jun Jiang1, Jun Sun1, Ye-Yun Li1, Qi Chen1, Tao Xia1, Xiao-Chun Wan1* Abstract Background: Tea is one of the most popular non-alcoholic beverages worldwide. However, the tea plant, Camellia sinensis, is difficult to culture in vitro, to transform, and has a large genome, rendering little genomic information available. Recent advances in large-scale RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provide a fast, cost-effective, and reliable approach to generate large expression datasets for functional genomic analysis, which is especially suitable for non-model species with un-sequenced genomes. Results: Using high-throughput Illumina RNA-seq, the transcriptome from poly (A)+ RNA of C. sinensis was analyzed at an unprecedented depth (2.59 gigabase pairs). Approximate 34.5 million reads were obtained, trimmed, and assembled into 127,094 unigenes, with an average length of 355 bp and an N50 of 506 bp, which consisted of 788 contig clusters and 126,306 singletons. This number of unigenes was 10-fold higher than existing C. sinensis sequences deposited in GenBank (as of August 2010). Sequence similarity analyses against six public databases (Uniprot, NR and COGs at NCBI, Pfam, InterPro and KEGG) found 55,088 unigenes that could be annotated with gene descriptions, conserved protein domains, or gene ontology terms. Some of the unigenes were assigned to putative metabolic pathways.