Structurally Cosmic Apostasy: the Atheist Occult World of H.P. Lovecraft Brian J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

The Nameless City

• The Nameless City by H. P. Lovecraft January 1921 • hen I drew nigh1 the nameless city I knew Wit was accursed.2 I was travelling in a parched3 and terrible valley under the moon, and afar4 I saw it protruding5 uncannily6 above the sands as parts of a corpse may protrude from an ill-made grave.7 Fear spoke from the age-worn stones of this hoary8 survi- vor of the deluge,9 this great-grandmother of the eldest pyramid; and a viewless aura repelled me and bade me retreat from antique and sinister secrets that no man should see, and no man else had ever dared to see. Remote in the desert of Araby10 lies the nameless city, crumbling and inarticulate, its low walls nearly hid- den by the sands of uncounted ages. It must have been thus before the first stones of Memphis11 were laid, and while the bricks of Babylon12 were yet unbaked. There is no legend so old as to give it a name, or to recall that 1) Near, archaic. 2) Cursed, archaic. 3) Dried. 4) Far away. 5) Sticking out. 6) Uncanny: strange, and mysteriously unsettling (as if supernatu- ral); weird. 7) From “The Festival” (Oct. 1923): “... and I saw that it was a bury- ing-ground where black gravestones stuck ghoulishly through the snow like the decayed fingernails of a gigantic corpse.” 8) White or gray with age. 9) A deluge is a great flood. In this case, he is referring to the bibli- cal flood of Noah as a way of indicating great age. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft Daniel M. Look St. Lawrence University Introduction My cynicism and skepticism are increasing, and from an entirely new cause – the Einstein theory. The latest eclipse observations seem to place this system among the facts which cannot be dismissed, and assumedly it removes the last hold which reality or the universe can have on the independent mind. All is chance, accident, and ephemeral illusion - a fly may be greater than Arcturus, and Durfee Hill may surpass Mount Everest - assuming them to be removed from the present planet and differently environed in the continuum of space-time. All the cosmos is a jest, and fit to be treated only as a jest, and one thing is as true as another. 1 Howard Philips Lovecraft lived in a time of great scientific and mathematical advancement. The late 1800s to the early 1900s saw the discovery of x-rays, the identification of the electron, work on the structure of the atom, breakthroughs in the mathematical exploration of higher dimensions and alternate geometries, and, of course, Einstein's work on relativity. From his work on relativity, Einstein postulated that rays of light could be bent by celestial objects with a large enough gravitational pull. In 1919 and 1922 measurements were made during two eclipses that added support to this notion. This left Lovecraft unsettled, as seen in the above quote from a 1923 letter to James F. Morton. Lovecraft's distress is that it seems we can no longer trust our primary means of understanding the world around us. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

This Paper Examines the Role of Media Technologies in the Horror

Monstrous and Haunted Media: H. P. Lovecraft and Early Twentieth-Century Communications Technology James Kneale his paper examines the role of media technologies in the horror fic- tion of the American author H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937). Historical geographies of media must cover more than questions of the distri- Tbution and diffusion of media objects, or histories of media representations of space and place. Media forms are both durable and portable, extending and mediating social relations in time and space, and as such they allow us to explore histories of time-space experience. After exploring recent work on the closely intertwined histories of science and the occult in late nine- teenth-century America and Europe, the discussion moves on to consider the particular case of those contemporaneous media technologies which became “haunted” almost as soon as they were invented. In many ways these hauntings echo earlier responses to the printed word, something which has been overlooked by historians of recent media. Developing these ideas I then suggest that media can be monstrous because monstrosity is centrally bound up with representation. Horrific and fantastic fictions lend themselves to explorations of these ideas because their narratives revolve around attempts to witness impossible things and to prove their existence, tasks which involve not only the human senses but those technologies de- signed to extend and improve them: the media. The remainder of the paper is comprised of close readings of several of Lovecraft’s stories which sug- gest that mediation allowed Lovecraft to reveal monstrosity but also to hold it at a distance, to hide and to distort it. -

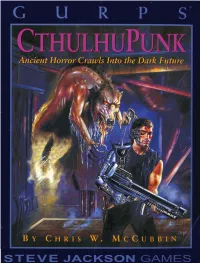

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls Into the Dark Future

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls into the Dark Future By Chris W. McCubbin Edited by Scott D. Haring Cover by Albert Slark Illustrated by Dan Smith GURPS System Design by Steve Jackson Scott Haring, Managing Editor Page Layout, Typography and Interior Production by Rick Martin Cover Production by Jeff Koke Art Direction by Lillian Butler Print Buying by Andrew Hartsock and Monica Stephens Dana Blankenship, Sales Manager Thanks to Dm Smith Additional Material by David Ellis Dickerson Bibliographic information compiled by Chris Jarocha-Emst Proofreading by Spike Y. Jones Playtesters: Bob Angell, Sean Barrett, Kaye Barry, C. Milton Beeghly, James Cloos, Mike DeSanto, Morgan Goulet, David G. Haren, Dave Magnenat, Virginia L. Nelson, James Rouse, Karen Sakamoto, Michael Sullivan and Craig Tsuchiya GURPS and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. Pyramid and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. Cull of Cihulhu is a trademark of Chaosium Inc. and is used by permission. Elder Sign art (p. 55) used by permission of Chaosium Inc. GURPS CihuIhuPunk is copyright 0 1995 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A ISBN 1-55634-288-8 Introduction ................................ 4 Central and South America ..27 Hacker ..................................43 About GURPS ............................4 The Pacific Rim ...................27 -

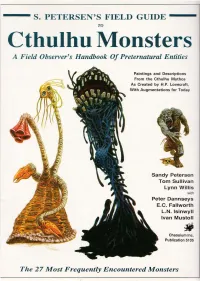

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Mi-Go 1 Mi-Go

Mi-go 1 Mi-go An interpretation of the Mi-Go by Ruud Dirven Mi-go ("The Abominable Ones") is a Himalayan nickname for a race of extraterrestrials in the Cthulhu Mythos created by H. P. Lovecraft and others. The name was first applied to the creatures in Lovecraft's short story "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931), elaborating on a reference to 'What fungi sprout in Yuggoth' in his sonnet cycle Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30) which described the contrasting vegetation on alien dream-worlds. Summary The "Mi-go" are large, pinkish, fungoid, crustacean-like entities the size of a man; where a head would be, they have a "convoluted ellipsoid" composed of pyramided, fleshy rings and covered in antennae. According to two reports in the original short story, their bodies consist of a form of matter that does not occur naturally on Earth; for this reason, they do not register on ordinary photographic film. They are capable of going into suspended animation until softened and reheated by the sun or some other source of heat. They are about five feet (1.5 m) long, and their crustacean-like bodies bear numerous sets of paired appendages. They possess a pair of membranous bat-like wings which are used to fly through the "aether" of outer space (a scientific concept which is now discredited). The wings do not function well on Earth. Several other races in Lovecraft's Mythos also have wings like these. The Mi-go can transport humans from Earth to Pluto (and beyond) and back again by removing the subject's brain and placing it into a "brain cylinder", which can be attached to external devices to allow it to see, hear, and speak. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature.