Digital Technology and Innovative Poetry Tom Jenks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

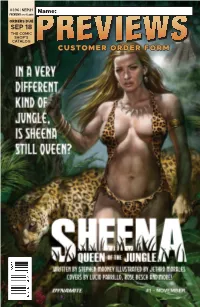

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

A Stylistic Approach to the God of Small Things Written by Arundhati Roy

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of English 2007 A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy Wing Yi, Monica CHAN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chan, W. Y. M. (2007). A stylistic approach to the God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/eng_etd.2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY CHAN WING YI MONICA MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2007 A STYLISTIC APPROACH TO THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS WRITTEN BY ARUNDHATI ROY by CHAN Wing Yi Monica A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in English Lingnan University 2007 ABSTRACT A Stylistic Approach to The God of Small Things written by Arundhati Roy by CHAN Wing Yi Monica Master of Philosophy This thesis presents a creative-analytical hybrid production in relation to the stylistic distinctiveness in The God of Small Things, the debut novel of Arundhati Roy. -

Proquest Dissertations

REPROGRAMMING THE LYRIC: A GENRE APPROACH FOR CONTEMPORARY DIGITAL POETRY HOLLY DUPEJ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATIONS AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38769-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38769-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech with Facebook Flarf: the Role of User Practices in Regulating Hate Speech on Facebook

The Fibreculture Journal issn: 1449-1443 DIGITAL MEDIA + NETWORKS + TRANSDISCIPLINARY CRITIQUE issue 23: General Issue 2014 FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech With Facebook Flarf: The Role of User Practices in Regulating Hate Speech on Facebook. Benjamin Abraham University of Western Sydney Abstract: This article makes a case study of ‘flarfing’ (a creative Facebook user practice with roots in found-text poetry) in order to contribute to an understanding of the potentials and limitations facing users of online social networking sites who wish to address the issue of online hate speech. The practice of ‘flarfing’ involves users posting ‘blue text’ hyperlinked Facebook page names into status updates and comment threads. Facebook flarf sends a visible, though often non-literal, message to offenders and onlookers about what kinds of speech the responding activist(s) find (un)acceptable in online discussion, belonging to a category of agonistic online activism that repurposes the tools of internet trolling for activist ends. I argue this practice represents users attempting to ‘take responsibility’ for the culture of online spaces they inhabit, promoting intolerance to hate speech online. Careful consideration of the limits of flarf’s efficacy within Facebook’s specific regulatory environment shows the extent to which this practice and similar responses to online hate speech are constrained by the platforms on which they exist. 47 FCJ-170 fibreculturejournal.org FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech With Facebook Flarf Introduction A recent spate of high profile cases of online abuse has raised awareness of the amount, volume and regularity of abuse and hate speech that women and minorities routinely attract online. -

Spam As the Inheritor of High Modernism

forty-five.com / papers /22 W@r aga1nst the F1lters: Spam as the Inheritor of High Modernism Octavian Esanu For some time, I have been captivated by a form of writing Reviewed by David Gissen that has been captivating my email inbox. Dictionaries define spam as intrusive, internet-mediated a d v e r t i s i n g — a d e fi n i t i o n w h o s e i n t e r e s t l i e s i nits s u g g e s t i o n o f h o w m u c h n o n - i n t r u s i v e a d v e r t i s i n g i s a l r e a d y a r o u n d u s . S p a m i s n o t l i k e t h i s a m b i e n t a d v e r t i s i n g , o f c o u r s e . I t i s p u r e i n t e n t i o n a l i t y . It resembles those bloodthirsty rainforest leeches with s u c k e r s a t b o t h e n d s t h a t w i l l g e t t o y o u r b l o o d n o m a t t e r h o w s a f e y o u m i g h t f e e l b e n e a t h l a y e r s o f p a n t s , s o c k s , a n d s n e a k e r s . -

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE @Comicartfest 12-14 October 2018 Main Funder Kendal, Cumbria 2 the LAKES INTERNATIONAL COMIC ART FESTIVAL 2018

LIMITED FESTIVAL PASSES AVAILABLE BUY NOW THE LAKES INTERNATIONAL COMIC ART FESTIVAL 2018 FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE @comicartfest www.comicartfestival.com 12-14 October 2018 Main Funder Kendal, Cumbria 2 THE LAKES INTERNATIONAL COMIC ART FESTIVAL 2018 INTRODUCTION Welcome festival-goers. A sincere thank you to our regulars for their steadfast support and a warm welcome to newcomers for giving LICAF a go. This year is our sixth festival and we continue to refine, adapt and add to our programme to keep it relevant, fresh and challenging too. This year we have more special guests than ever before, an expanded Clocktower (which maintains its intimacy), a bigger social, “out of hours” programme and more new countries represented including Russia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, India and Nepal. Our partnership with Wacom, Lancaster University, the University of Cumbria and the National Cartoonists’ Society continues to grow and we welcome our new partners, Dundee University and Lyon BD Festival, with whom we expect to work more closely over coming months. We also welcome back Amiens Comics Festival, the Finnish Institute, a fresh delegation from the Netherlands and representatives from the Flemish EVENTS Literature Fund. Times, dates and venues for A huge thank you to our funders this year’s amazing events and partners but most of all to our 4 tremendous team of volunteers without whom we’d be lost, fumbling around in a sea of intent! Julie, Carole, Sharon, Marianne, Aileen, Matt, Nick, Steve, John, Jo and Chris CONTENTS 4 Festival Overview 5 Festival -

Exercices De Style” As a Visual Language Learning Tool †

Proceedings Visual Story Telling. The Queneau’s “Exercices de † Style” as a Visual Language Learning Tool Letizia Bollini Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126 Milano, Italy; [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-6448 (ext. 3576) † Presented at the International and Interdisciplinary Conference IMMAGINI? Image and Imagination between Representation, Communication, Education and Psychology, Brixen, Italy, 27–28 November 2017. Published: 28 November 2017 Abstract: The paper discusses the importance and role of visual story telling skills in the field of non-designers education as an effective ideation and expressive medium. It presents the process and results of an experimental design workshop held as a warm up activity inside the Visual Design and Visual Communication and Interface Design classes at University of Milano-Bicocca since 2002. The Exercises de Style written by Queneau are the field of exploration of the intertextual translation from text to graphical representation using principles and rules of the visual language. Keywords: visual story telling; visual rhetoric; intertextual translation; visual language; visual design; graphic design 1. Introduction Visual story telling has become one of the most important strategies and tool in the field of communication. In the digital ecosystem and social networks, it is mostly practiced in whom are based on pictures and photos sharing such as Instagram, Pinterest, Tumbler and Flickr’ [1]. In an image’s society, the visual language itself is a transversal competence—a soft skill—required in many professional activities and personal branding construction. Nevertheless, our educational system provides little space for design, historical and critical approach to a figurative culture. -

BTPS 2020 Canada Fall Catalog

BAKER & TAYLOR PUBLISHER SERVICES BAKER & TAYLOR CANADA SPRING 2020 www.btpubservices.com For a complete list of titles, visit Baker & Taylor Publisher Services on Edelweiss. CAnada • Spring 2020 888.814.0208 (toll free) or 567.215.0030 BAKER & TAYLOR NOTES Vice President of Client Services Director of National Accounts Director of Marketing Jeff Tegge Andi Richman Matt Warner 312.438.7960 973.495.0690 419.564.4931 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Vice President of Sales Director of Special Sales/Gift Graphic & Web Designer Mark Hillesheim Christina Noriega Jake Schritz 646.670.1710 419.606.2133 567.215.0030 x1432 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Director of National Sales Sales Administration Coordinator Remittance, Warehouse & General Address Dan Verdick Emilee Graehling 30 Amberwood Parkway 651.226.5572 567.215.0030 x1409 Ashland, OH 44805 [email protected] [email protected] CONTACT & ORDERING INFORMATION Contact Customer Service Fraser Direct 905.877.4411 8300 Lawson Road [email protected] Milton, Ontario, Canada L9T 0A4 CANADIAN SALES REPRESENTATIVES Ampersand, Inc. Ontario Evette Sintichakis British Columbia/Alberta/Saskatchewan/ Saffron Beckwith 416.703.0666, ext. 121 Manitoba/Yukon/Nunavut/NWT 416.703.0066, ext. 124 Toll-free 866.736.5620 [email protected] Ali Hewett Toll-free 866.736.5620 Tel 604.448.7166 [email protected] Jenny Enriquez [email protected] Morgen Young 416.703.0666, ext. 126 Toll-free 866.736.5620 Dani Farmer 416.703.0666, ext. 128 [email protected] Tel 604.448.7168 Toll-free 866.736.5620 [email protected] [email protected] Head Office: Suite 213, 321 Carlaw Avenue, Toronto, Jessica Price Laureen Cusak ON, M4M 2S1 Tel 604.448.7170 416.703.0666, ext. -

Am. Singer/Songwriter,Flott.Covret Av Bl.A Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt I 1993

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP A ATCO REC7567- AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 1995 EUR CD 92418-2 ACKLES, DAVID FIVE & DIME 2004 RAVENREC. AUST. CD Am. singer/songwriter,flott.Covret av bl.a Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt i 1993. Cd utg. fra 2004 XL RECORDINGS ADELE 21 2011 EUR CD XLLP 520 ADELE 25 2015 XLCD 740 EUR CD ADIEMUS SONGS OF SANCTUARY 1995 CDVE 925 HOL CD Prosjektet til ex Soft Machine medlem Karl Jenkins. Middelalderstemnig og mye flott koring. AEROSMITH PUMP 1989 GEFFEN RECORDS USA CD Med Linda Hoyle på flott vocal, Mo Foster, Mike Jupp.Cover av Keef. Høy verdi på original vinyl AFFINITY AFFINITY 1970 VERTIGO UK CD Vertigo swirl. AFTER CRYING OVERGROUND MUSIC 1990 ROCK SYMPHONY EUR CD Bulgarsk progband, veldig bra. Tysk eksperimentell /elektronisk /prog musikk. Østen insirert album etter Egyptbesøk. Lp utgitt AGITATION FREE MALESCH 2008 SPV 42782 GER CD 1972. AIR MOON SAFARI 1998 CDV 2848 EUR CD Frank duo, mye keyboard og synthes. VIRGIN 72435 966002 AIR TALKIE WALKIE 2004 EUR CD 8 ALBION BAND ALBION SUNRISE 1994-1999 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CDX2 Britisk folkrock med bl.a A.Hutchings,S.Nicol ex.Fairport Convention ALBION BAND M/ S.COLLINS NO ROSES 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CD Britisk folk rock. Opprinnelig på Pegasus Rec. I 1971. CD utg fra 2004. Shirley Collins på vocal. ALICE IN CHAINS DIRT 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Godt album, flere gode låter, bl.a Down in a hole. ALICE IN CHAINS SAP 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Ep utgivelse med 4 sterke låter, Brother, Got me wrong, Right turn og I am inside ALICE IN CHAINS ALICE IN CHAINS 1995 COLOMBIA USA CD Tungt, smådystert og bra. -

Rui Torres & Sandy Baldwin

CONFERENCE, FESTIVAL, EXHIBITS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS AND CATALOGS EDITORS: RUI TORRES & SANDY BALDWIN Conference Book of Abstracts edited by Rui Torres and Sandy Baldwin Festival Catalog edited by Rui Torres and Sandy Baldwin Exhibits Catalog edited by Rui Torres with texts by the Curators: • Affiliations - Remix and Intervene: Computing Sound and Visual Poetry: Álvaro Seiça and Daniela Côrtes Maduro • Communities - Signs, Actions, Codes: Bruno Ministro and Sandra Guerreiro Dias • Translations - Translating, Transducing, Transcoding: Ana Marques da Silva and Diogo Marques • E-lit for Kids: Mark Marino, Astrid Ensslin, María Goicoechea, and Lucas Ramada Prieto. EDIÇÕES UNIVERSIDADE FERNANDO PESSOA PORTO . 2017 CONTENts INTRODUCTION ................................................. 7 CONFERENCE .................................................... 15 FESTIVAL ............................................................ 475 EXHIBITS ............................................................. 591 INTRODUCTION The ELO (Electronic Literature Organization) organized its 2017 Conference, Festi- val and Exhibits, from July 18-22, at University Fernando Pessoa, Porto, as well as several other venues located in the center of the historic city of Porto, Portugal. Titled Electronic Literature: Affiliations, Communities, Translations, ELO’17 pro- poses a reflection about dialogues and untold histories of electronic literature, providing a space for discussion about what exchanges, negotiations, and move- ments we can track in the field of electronic literature. -

Image Spam Detection: Problem and Existing Solution

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 02 | Feb 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Image Spam Detection: Problem and Existing Solution Anis Ismail1, Shadi Khawandi2, Firas Abdallah3 1,2,3Faculty of Technology, Lebanese University, Lebanon ----------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Today very important means of communication messaging spam, Internet forum spam, junk fax is the e-mail that allows people all over the world to transmissions, and file sharing network spam [1]. People communicate, share data, and perform business. Yet there is who create electronic spam are called spammers [2]. nothing worse than an inbox full of spam; i.e., information The generally accepted version for source of spam is that it crafted to be delivered to a large number of recipients against their wishes. In this paper, we present a numerous anti-spam comes from the Monty Python song, "Spam spam spam spam, methods and solutions that have been proposed and deployed, spam spam spam spam, lovely spam, wonderful spam…" Like but they are not effective because most mail servers rely on the song, spam is an endless repetition of worthless text. blacklists and rules engine leaving a big part on the user to Another thought maintains that it comes from the computer identify the spam, while others rely on filters that might carry group lab at the University of Southern California who gave high false positive rate. it the name because it has many of the same characteristics as the lunchmeat Spam that is nobody wants it or ever asks Key Words: E-mail, Spam, anti-spam, mail server, filter. -

The Imagined Voice 2017 JULY

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/58691 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Kyriakides, Y. Title: Imagined Voices : a poetics of Music-Text-Film Issue Date: 2017-12-21 Imagined Voices A Poetics of Music-Text-Film Yannis Kyriakides Imagined Voices A Poetics of Music-Text-Film Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 21 december 2017 klokke 15.00 uur door Yannis Kyriakides geboren te Limassol (CY) in 1969 Promotores Prof. Frans de Ruiter Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Marko Ciciliani Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Graz Copromotor Dr. Catherine Laws University of York/ Orpheus Instituut, Gent Promotiecommissie Prof.dr. Marcel Cobussen Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Nicolas Collins School of the Art Institute of Chicago Prof.dr. Sander van Maas Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof.dr. Cathy van Eck Bern University of the Arts Dr. Vincent Meelberg Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen/ docARTES, Gent Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Academy of Creative and Performing Arts (ACPA) Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 4 PART I: Three Voices 16 Chapter 1: The Mimetic Voice 17 1.1 Art Imitates 18 1.2 Cognitive Immersion 24 1.3 Vocal Embodiment 27 1.4 Subvocalisation 32 1.5 Inner Speech 35 1.6 Silent Voices 38 Chapter 2: The Diegetic Voice 41 2.1 Narration 43 2.2 Paratext 46 2.3 Narrational Network 48 2.4 Temporality